the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Feedback-based sea level rise impact modelling for integrated assessment models with FRISIAv1.0

Lennart Ramme

Benjamin Blanz

Christopher Wells

Tony E. Wong

William Schoenberg

Chris Smith

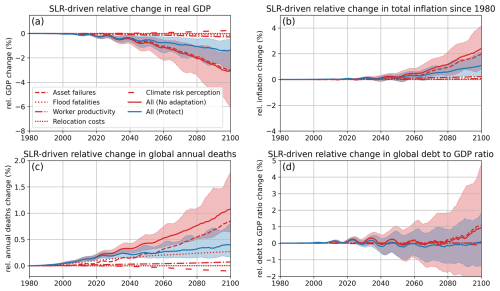

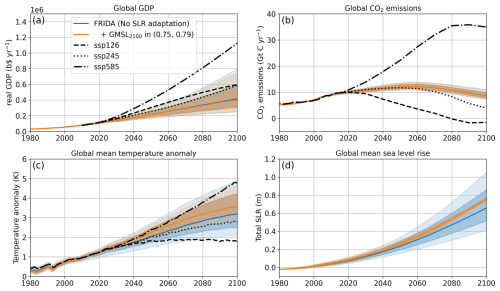

Global warming is expected to lead to a substantial rise in coastal sea levels by the end of the century, which imposes future impacts and adaptation challenges on the coastal zone. Capturing the socio-economic costs of sea level rise (SLR) is therefore an important component of climate impacts in integrated assessment models (IAMs). However, there is a lack of process-based models of SLR impacts with a focus on global, time-varying dynamics. Current SLR impact models often follow a cost-benefit analysis approach, fail to represent diverse pathways of SLR impacts, or do not include coastal adaptation. Here, we present the Feedback-based knowledge Repository for Integrated assessments of Sea level rise Impacts and Adaptation version 1.0 (FRISIAv1.0), a model designed for process-based, non-equilibrium IAMs that follows a system dynamics approach. FRISIA's SLR component is based on existing models of SLR, while its impact component is a substantially modified adaptation of the Coastal Impact and Adaptation Model (CIAM) for use in globally or regionally aggregated models. While a reduced-feedback version of FRISIA approximately reproduces CIAM results, the integration of additional feedbacks in FRISIA leads to emerging new behaviours, such as a potential peak and decline in SLR-driven storm surge damages in the early 22nd century, due to economic feedbacks in the coastal zone. When coupling FRISIA to an IAM, global GDP is reduced by 1.5 %–6.2 % (17th–83rd percentile range) under the mean SSP5-8.5 global-mean sea level rise from the IPCC's AR6 report (0.77 m by 2100) and no coastal adaptation, which is in the range of previous studies. The coupling of a diverse set of SLR impact streams from FRISIA into a system dynamics IAM has the advantage of leading to a wide range of socio-economic consequences that go beyond just a reduction in global GDP, such as an effect on inflation. Our simulations highlight the benefits of accounting for dynamic coastal feedback and coupling diverse SLR impact and cost strains to IAMs, and showcase that FRISIAv1.0 is a useful tool for doing so.

- Article

(7169 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Sea level rise (SLR) is one of the main consequences of anthropogenic climate change that society will experience over the coming decades to centuries. Global mean sea level (GMSL) is likely to rise between 0.3 and 1.6 m by the end of this century, depending on the scenario and given uncertainties surrounding GMSL projections (Fox-Kemper et al., 2021). This magnitude of sea level change can have multiple and possibly severe consequences for coastal communities; it is therefore critical to account for the impacts of SLR when projecting the socio-economic evolution of the world in the 21st century and quantifying the effects of global climate change (e.g. Parrado et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2021; Bachner et al., 2022; Magnan et al., 2022; Hermans et al., 2023; Cortés Arbués et al., 2024).

Integrated assessment models (IAMs) are designed to produce possible future socio-economic scenarios under anthropogenic climate change. One of the use cases of IAMs is to generate the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) (Riahi et al., 2017), which in turn are used to drive Earth system model simulations (Eyring et al., 2016) and to inform the assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (IPCC, 2021). Hence, a crucial component of IAMs is a realistic representation of the connections between the human and the natural domain. The implemented connection from the human domain to the climate system arises primarily from greenhouse gas and aerosol emissions, as well as land-use changes, which are often simulated directly within the IAM (Popp et al., 2017). However, going into the other direction, the effects of climate change on the human system are less straightforward and often not process-based (Calvin and Bond-Lamberty, 2018; Donges et al., 2021; Dietz, 2024). For example, a damage function might simply reduce the gross domestic product (GDP) depending on the temperature anomaly as originally proposed by Nordhaus (1977). Consequently, IAMs are often criticized for missing internal feedbacks and heterogeneity (Donges et al., 2017; Calvin and Bond-Lamberty, 2018; Keppo et al., 2021).

Within the typical IAM structure, the impacts of SLR are often represented by simple implementations, if included at all, as we describe in more detail in Sect. 2. Currently, more comprehensive SLR impact and adaptation formulations can be found in IAMs that are computable general equilibrium (CGE) models or those that employ cost-benefit analysis approaches (Waldhoff et al., 2014; Yumashev, 2020; Rennert et al., 2022). These models try to find cost-optimal pathways or maximize welfare by solving a given set of equations (Keppo et al., 2021). However, the realm of IAMs also encompasses more process-based models (Weyant, 2017), and a subset of those simulates forward on a time step basis without solving for cost-optimal pathways (Keppo et al., 2021). This modelling approach is part of the field of system dynamics, which focuses on the understanding of nonlinear complex systems by emphasising the feedback between components (Forrester, 1961; Sterman, 2000). Hence, for simplicity, we refer to these types of models as dynamic IAMs. Dynamic IAMs typically value dynamic complexity, that is, the interconnectedness of processes and model components, over process detail. This has the advantage of higher computational efficiency, increased transparency and a better representation of time-dependent behaviour, whole-system feedback and uncertainty (Weyant, 2017; Donges et al., 2017). However, there is no model for SLR impacts and adaptation that specifically meets these criteria for the use in dynamic IAMs. This is where our study comes in.

We present the Feedback-based knowledge Repository for Integrated assessments of Sea level rise Impacts and Adaptation (FRISIA) version 1.0, a newly developed model that aims to improve the representation of SLR impacts in global or regional dynamic IAMs. FRISIA's focus is on incorporating socio-economic feedback within the coastal zone that is missing in other SLR impact models and to provide a wide range of output streams that can be coupled to different parts of an IAM. Incorporating SLR impacts into IAMs with FRISIA will therefore improve the realism of the feedback from the natural to the human domain in these models.

Rising sea levels lead to increased coastal erosion, the intrusion of saltwater into coastal aquifers, and increases in the frequency and severity of extreme storm surges, leading to increased flood damages (Cazenave and Cozannet, 2014). At the same time, SLR is a slow process, happening on a time scale that is longer than the time it typically takes for capital and infrastructure to depreciate, so that actual damages from gradual flooding might be smaller (Desmet et al., 2021). Nevertheless, if not protected, low-lying areas within the coastal zone may become inundated so that people and economic assets are forced to migrate away from the coast (Lincke and Hinkel, 2021; Duijndam et al., 2022). Furthermore, there are multiple ways in which the coastal community can adapt to SLR, which range from raising flood protection, flood-proofing or raising existing structures, to renourishing of beaches or other forms of soft protection, and the planned retreat of assets and people from the coast (Oppenheimer et al., 2019; Tiggeloven et al., 2020). However, determining the optimal adaptation strategy is highly dependent upon the local geography, the socio-economic boundary conditions and potentially cultural heritage (Nazarnia et al., 2020; Bongarts Lebbe et al., 2021). Therefore, IAMs that model the global impacts of SLR must in principle rely on models that divide the coast into a large number of segments within which the geographical and socio-economic properties are approximately similar.

Most commonly used for breaking up the coast in smaller segments is the Dynamic Interactive Vulnerability Assessment (DIVA) database, which assesses damages based on the local conditions of 12 148 distinct coastal segments (Vafeidis et al., 2008; Hinkel and Klein, 2009; Hinkel et al., 2014; Lincke and Hinkel, 2018). The open-source Coastal Impact and Adaptation Model (CIAM) builds on the DIVA database and was designed to determine local SLR impacts and the optimal least-cost adaptation strategy to quantify the global economic impacts of SLR (Diaz, 2016). Expanding on the scope of the DIVA database, Depsky et al. (2023) have presented the DSCIM-Coastal platform, which provides a similar database as DIVA, but with major updates for all types of included information, which is named the Sea Level Impacts Input Dataset by Elevation, Region and Scenarios (SLIIDERS). DSCIM-Coastal also provides an updated python version of CIAM (pyCIAM) and is available as open-source software. Models like CIAM and DSCIM-Coastal are suitable tools for quantifying the global costs and damages associated with SLR and characterizing uncertainty in the economically-efficient adaptation strategies across a wide spatial domain (Wong et al., 2022; Depsky et al., 2023). For example, both models were included in a recent accounting of the social-cost of carbon (SCC) (Rennert et al., 2022; ImpactLab, 2023). Rennert et al. (2022) found that accounting for impacts of SLR only adds around 1 %–2 % to the total SCC. However, the model assumed optimal adaptation strategies, and as SLR damages occur far into the future, the costs associated with the impacts of SLR are strongly discounted (a discount rate of 2 % is used in that study). Similar to the GIVE model used in Rennert et al. (2022), the IMAGE model also tracks local SLR and its impacts based on the DIVA database (Stehfest et al., 2014). Nevertheless, the complexity of CIAM or DSCIM-Coastal precludes their use within IAMs that require a computationally more efficient model. Consequently, the representation of sea level rise impacts is much simpler in most other existing IAMs.

Some IAMs, such as the highly aggregated DICE model (Nordhaus, 2017; Barrage and Nordhaus, 2024), the more process-based REMIND (Baumstark et al., 2021) model, or the system dynamics model FeliX (Ye et al., 2024) do not explicitly track SLR, instead incorporating damage functions that are only a function of the global mean temperature. While this may be a tenuous but defensible assumption in scenarios with continuous warming, this approach becomes problematic in scenarios of mitigated global warming. In this case the rate of global warming slows down or even reverses, but global mean sea level continues to rise in the long term due to inertia and hysteresis effects of the ocean and the ice sheets (Li et al., 2020). Furthermore, the contribution of land water storage (LWS) changes to GMSL rise is more directly a function of socio-economic conditions and not of temperature (Reager et al., 2016). Going a bit further, the PAGE model explicitly tracks GMSL as a function of the global mean temperature anomaly and calculates damages that account for local per capita income and adaptation (Moore et al., 2018; Yumashev, 2020). A more comprehensive formulation of SLR damages and adaptation in an integrated assessment model is implemented in the FUND model (Tol, 2007). In FUND, adaptation to SLR is represented based on a cost-benefit analysis, accounting explicitly for the costs of wetland and dryland loss, coastal protection and migration, and including the effect of expected future SLR.

In summary, many IAMs do not specifically account for SLR impacts (e.g., DICE, REMIND, FeliX) and those that do are often aggregated computable general equilibrium (CGE) models (PAGE, FUND). Only the GIVE and IMAGE models incorporate more comprehensive SLR impact formulations, but their high spatial resolution makes them difficult to use in more aggregated IAMs that focus on dynamic complexity instead of process-detail. This means that, while all the above-mentioned models are well established and have their use cases, there is a lack of a process-based SLR impact and adaptation model for use in dynamic IAMs. Nevertheless, also CGE models and other types of IAMs can benefit from an improved and computationally efficient implementation of SLR impacts and adaptation.

The FRISIA model version 1.0 that we present in this manuscript is a model for SLR and the corresponding impacts and adaptation to it, which fills the aforementioned gap. The model is named after the Frisia region along the southern coast of the North Sea, which has historically experienced major SLR and storm surge damages (Bungenstock et al., 2021; Von Storch and Woth, 2008). The name was also chosen in reference to the new integrated assessment model FRIDA (Schoenberg et al., 2025a), for which FRISIA was initially developed, even though FRISIA is an independent model that can be run uncoupled or coupled to other IAMs. FRIDA follows the same system dynamics modelling approach as FRISIA, making it the natural home of our model. As a system dynamics model, in FRISIA we try to capture the inter-relatedness of SLR-related processes, but at the same time we sacrifice process-detail and resolution for dynamic complexity. Because we also value transparency and accessibility, FRISIA is developed in Python and made available in an open source GitHub repository (see Code Availability section). In Sect. 3 we describe the SLR model and FRISIAv1.0 formulation of SLR impacts and adaptation. In Sects. 4 and 5 we then present results of our model when used in an uncoupled mode, whereas in Sect. 6 we couple the model to FRIDA and explore the resulting impacts.

3.1 Sea level rise model formulation and projections

The first step to address the impacts of SLR is to calculate the magnitude of GMSL rise under global warming. There are many models that are designed to quantify GMSL within the framework of IAMs or similar use cases (Rahmstorf, 2007; Nauels et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2017). The simplest possible choice that could easily be used in an IAM would be the semi-empirical approach of Rahmstorf (2007), which relates the annual change in GMSL linearly to the global mean surface air temperature (GSAT) anomaly with respect to the pre-industrial period. However, while this fits GMSL observational data and leads to projections for 2100 that are approximately in line with IPCC estimates (Fox-Kemper et al., 2021), the approach neglects the non-linear nature of many of the processes contributing to changes in GMSL, and it is not certain that the relationship remains valid in the more distant future. Furthermore, the same rate of GMSL rise can translate into different rates of local SLR, due to the locally varying impacts of the different SLR contributions (Palmer et al., 2020; Fox-Kemper et al., 2021). Hence, as we value dynamic complexity and process-based relationships, and since FRISIA aims at also being suitable for regionalised IAMs, we explicitly model the five most important contributions to GMSL rise: thermal expansion of the ocean, changes in land water storage, the melting of mountain glaciers, the Antarctic ice sheet (AntIS) and the Greenland ice sheet (GrIS). Again, all these processes are already represented in existing models of GMSL rise, and we highlight that the individual components of FRISIA are largely based on the two existing models from the BRICK (Wong et al., 2017) and MAGICC (Nauels et al., 2017) modelling frameworks. Nevertheless, as small modifications were made to some of the parameterisations, and in order to provide comprehensive model documentation, we describe the formulation of the individual GMSL rise contributions in detail in Appendix A.

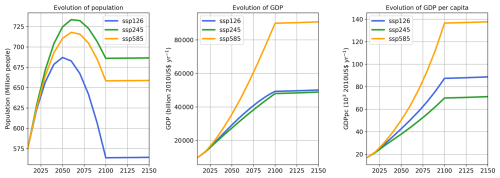

We drive the SLR model with time series of GSAT and ocean heat content (OHC) anomalies from FaIR v2.1.1 (Smith et al., 2018; Leach et al., 2021), which is a well-established climate emulator that reproduces the behaviour of the CMIP6 ensemble and provides a range of possible future projections. We use a calibration of FaIR (v1.1.0) that is constrained to observed time series of global mean surface temperature for 1850–2019 and OHC change for 1971–2018 along with IPCC assessments of the uncertainty distributions of equilibrium climate sensitivity, transient climate response, present-day aerosol forcing and present-day CO2 concentrations (Smith et al., 2024), driven with emissions scenarios from the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report and containing 1001 ensemble members. The GSAT anomaly can be used as the driver of the three GMSL rise contributions that are related to the melting of ice. Furthermore, OHC change is required to calculate the thermosteric component of GMSL rise, while the land water storage component is driven by socio-economic variables. For the latter, when running uncoupled to an IAM, we use global population data and projections taken from the IIASA SSP database (Riahi et al., 2017; Samir and Lutz, 2017). When running coupled to an IAM, all these variables are often readily available endogenously.

Modelling GMSL rise comes with a large range of structural and parametric uncertainties at the level of the individual SLR processes, which add to the uncertainty in the variables that drive GMSL rise. Therefore, model calibration is essential to produce realistic outcomes that fit with historical observations and match future projections from more detailed models (Fox-Kemper et al., 2021). Two different calibration targets are therefore used here for calibrating our model. We make sure that observational data for the individual contributions to GMSL rise are matched, which we take from Horwath et al. (2021). At the same time, we calibrate to the GMSL projections from Chapter 9 of the IPCC's Working Group 1 contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6, Fox-Kemper et al., 2021) for three scenarios (SSP1-1.9, SSP2-4.5, SSP5-8.5), covering the maximum range of plausible future pathways represented by the SSPs.

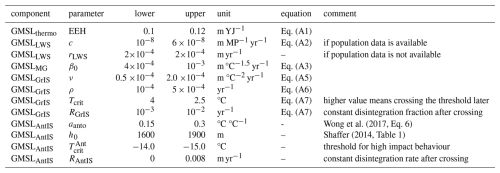

Given the large uncertainties in the parameter values, as well as the structure itself, we value simplicity over detail during the calibration process. Therefore, for each of the five components of GMSL rise, we define a ”scale factor” that can be varied between 0 and 1, which respectively correspond to the minimum and maximum contribution of the individual components. These factors are varied randomly and independently for each member of the FaIR input ensemble, so that the resulting time series of GMSL rise include uncertainty from both climate projections and SLR responses. Inside the SLR formulation for each component, this factor is used to scale a set of one to four parameters within a predefined range simultaneously. The calibrated range of the uncertainty parameters is given in Table B1. While this approach does not cover the full parametric uncertainty, it makes sure that parameter combinations leading to unrealistic outcomes are avoided, and it is sufficient to cover the uncertainty ranges in AR6. These parameter ranges are defined during the calibration process and are described in Appendix A.

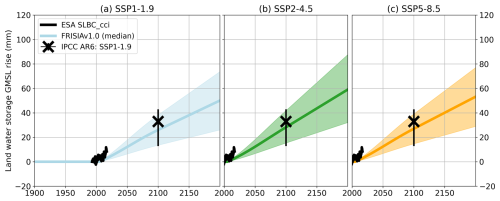

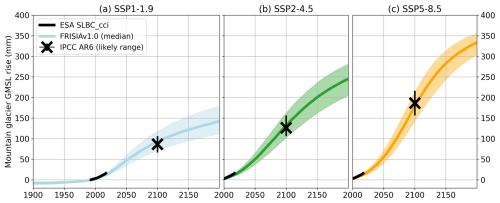

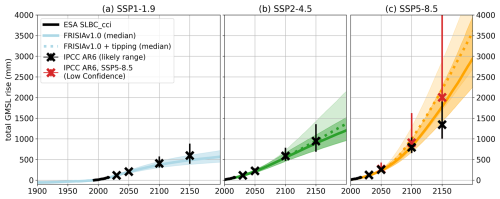

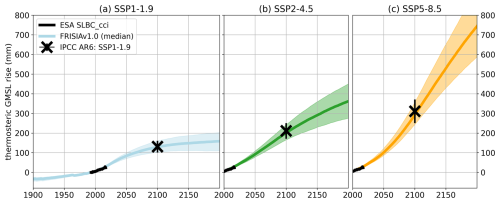

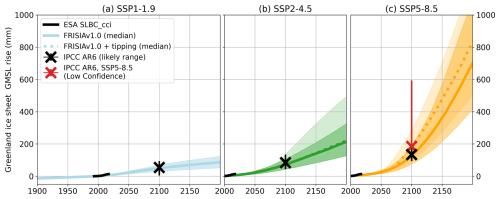

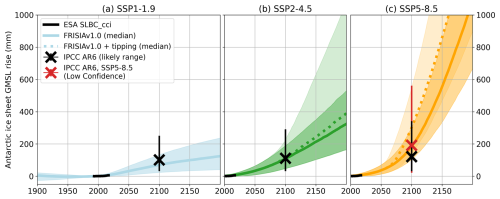

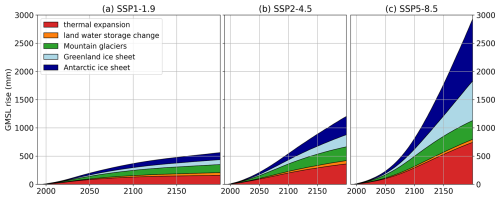

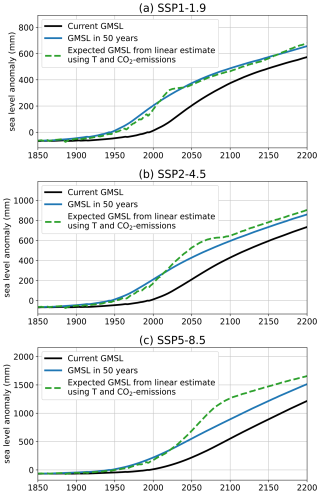

In Fig. 1, we present FRISIA projections of the total GMSL rise, calculated as the sum of the five individual contributions. The internal model parameters are hand-calibrated to match the projections of the individual contributions for the year 2100 presented in AR6 (Table 9.9 in Fox-Kemper et al., 2021), but not to specifically match those of the total GMSL rise shown in Fig. 1. Nevertheless, the projected total GMSL rise fits well with estimated median values and uncertainty ranges until 2100. However, in the 22nd century, our model projects a larger sensitivity to the long-term evolution of the GSAT anomaly, leading to values of GMSL rise that are slightly below the AR6 estimates for 2150 in SSP1-1.9, while they are above the estimates for SSP5-8.5 (excluding the “Low Confidence” scenario of very high SLR). This is not because of the temperature time series used, but a consequence of the parametrisations of the model. For the intermediate scenario SSP2-4.5 the fit is good even for the year 2150, and we note that IAMs rarely simulate time horizons that go beyond the year 2100, due to the sizeable uncertainties in the socioeconomic evolution on such long time scales.

Figure 1The total GMSL rise as projected with FRISIA for SSP1-1.9 (a), SSP2-4.5 (b) and SSP5-8.5 (c) compared to data of the European Space Agency (ESA) Sea Level Budget Closure – Climate Change Initiative (SLBC_CCI) project (Horwath et al., 2021, black curve) and aligned to the year 1993. The solid and dashed curves are the cases with deactivated and activated high impact behaviour parameterization in FRISIA, respectively. Also given are the median estimates for 2030, 2050, 2100 and 2150 from AR6 (Fox-Kemper et al., 2021). We additionally present the “Low Confidence” scenario as the red error bars for SSP5-8.5, which includes uncertain high impact processes. Given error bars are the “likely ranges” from Table 9.9 in Fox-Kemper et al. (2021), which represent the range with a 66 % likelihood of occurrence in the IPCC's calibrated language. Correspondingly, the median and the 17th–83rd percentile ranges for the data from FRISIA are shown as lines and shaded area, respectively.

3.2 SLR impacts and adaptation model

The impacts and adaptation component of FRISIA is designed on the basis of the global coastal impact and adaptation model CIAM (Diaz, 2016; Wong et al., 2022). The choice of CIAM and hence the DIVA database over DSCIM-Coastal was made because of initial data availability, but we discuss a potential future use of DSCIM-Coastal in the discussion section (Sect. 7).

In contrast to CIAM, FRISIAv1.0 is set up as a global or regionally aggregated model, because it is designed for use in IAMs, in which computational speed and interactive coupling are valued. FRISIAv1.0 is designed for dynamic IAMs that integrate forward in time. Therefore, the model deviates from CIAM in that it uses a comparably small time step of one year, and only calculates the annual costs over this time step. This means that FRISIA does not calculate the costs of all possible adaptation strategies and then chooses the strategy that minimises the costs over a given time horizon. Instead, the model simply calculates the evolution of coastal assets and population, as well as the coastal protection level and annual damages and costs for a user-defined adaptation strategy. While this approach does not inform the user about the cost-optimal strategy, which would not be informative on a coarse aggregation level and often does not represent reality, there are some key advantages. First, the chosen approach allows for an easier analysis of feedbacks within a given adaptation strategy. Second, it gives an improved representation of the annual evolution of impacts. Third, it enables an integration of an endogenous framework of decision making in the future, which takes into account more aspects than just cost-optimisation.

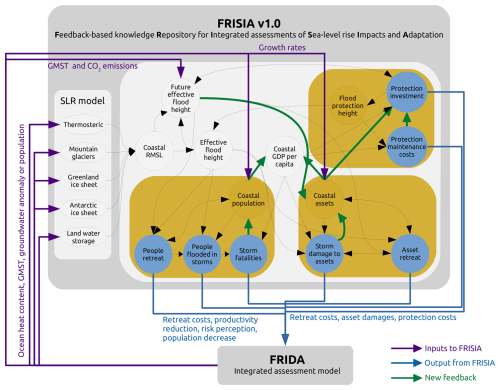

In this section we discuss all the components of the impacts and adaptation model of FRISIAv1.0 in detail. A schematic of the model is shown in Fig. 2, which shows the logical flow of information between all components. We organize the model description based on this. In the first subsection we describe how FRISIA generally uses information from CIAM and the DIVA database, as well as how other input data is used to drive the model. We then continue with a description of how we derive coastal flooding and the exposure of assets and people to SLR damages from time series of GMSL and its subcomponents. The remaining three subsections then describe the technical implementation of how flood protection, as well as the dynamics of coastal assets and coastal population are modelled (yellow boxes in Fig. 2).

Figure 2Schematic overview of the FRISIA model and how it is coupled to FRIDA (see Sect. 6). In an uncoupled version, the inputs to FRISIA (purple arrows) come from external datasets and the outputs (blue arrows) do not feed back onto the model that creates the input. The green arrows represent new connections that are made in FRISIA compared to CIAM, and which are turned off in Sect. 4.2. Blue circles are used for variables that represent SLR impacts.

3.2.1 Model inputs

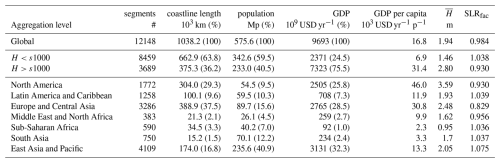

We aggregate data from the DIVA database in order to include coastal information in FRISIA. In the current version there are three types of aggregation: (1) a global setup, including all segments from the DIVA database; (2) a bipolar setup, where these segments are separated into those with a dike height that is higher than the height of a storm surge with a return period of 1000 years (“well protected” segments) and those where this is not the case (“less protected” segments); and (3) a regional setup, where the DIVA segments are separated into the seven World Bank regions (World Bank Group, 2025). These data are stored in input files in the repository and loaded into the model at initialisation, depending on the chosen aggregation type. For each aggregation type we store the coastline length, the initial flood protection height, coastal assets and population. The population data is taken from the DIVA dataset directly, and asset values are assumed to be proportional to coastal GDP data (see Sect. 3.2.4), which is calculated using the DIVA population and country-level GDP per capita data (Riahi et al., 2017; Cuaresma, 2017).

FRISIA also reads in SLR weights for each coastal zone. These weights are taken from Slangen et al. (2014) and aggregated by calculating a population-weighted mean over all the segments within each coastal zone. There are weights for the individual SLR components, whereby those for thermal expansion and land water storage are always equal to one. When the respective time series of the SLR components are provided by the user, FRISIA will use these weights to calculate the local SLR for each coastal zone. There is an additional weight for the total GMSL rise, based on fitting the local SLR in each coastal zone to GMSL rise in the SSP5-8.5 scenario. This represents a simplified approach that is only used in case there is only total GMSL rise as input to the model, or when calculating expected SLR in the future, as described in Sect. 3.2.3.

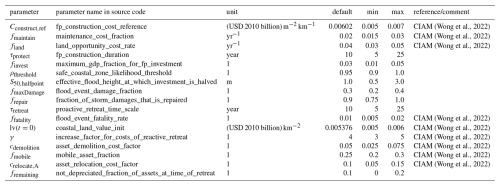

The overall approach of FRISIAv1.0 is to use the same model formulations as CIAM, where appropriate in a highly aggregated model like FRISIA. This is the case for the general flood protection construction and maintenance formulations, which are identical to those in CIAM, except for the calculation of the desired protection level and the available amount of money for investment (Sect. 3.2.3). Also the calculations of land values, opportunity costs, and relocation costs use the same formulations as CIAM. Where FRISIA uses the same model formulations as CIAM, it also uses the same parameter values, but with FRISIA we added approximated ranges of uncertainty for all of the parameters, including those of the new model formulations unique to FRISIA (see Table B3).

For the baseline growth of asset and population stocks, the offline version of FRISIA uses the same input data from the SSP database as CIAM (Riahi et al., 2017; Cuaresma, 2017). This means that coastal population and GDP per capita growth rates are based on country-level rates, which are extended with constant values beyond 2100 (Fig. B7), leading to visible kinks in that year for some variables. These are applied to each coastal segments, before aggregating the information into GDP and population data for each coastal zone. When using FRISIA coupled to an IAM, the IAM should provide the growth rates directly.

We have now discussed the input data for coastal assets and population, how coastal SLR is calculated from time series of GMSL rise and for which parts of FRISIA CIAM formulations are applied directly. However, this is not yet enough local information in order to properly calculate storm surge damages and inundation of people and assets, i.e. coastal flooding.

3.2.2 Modelling coastal flooding

In order to model coastal flooding, FRISIA also makes use of processed data from the CIAM model, which is ultimately based on the DIVA database, but it was not possible to use the CIAM formulations for this directly. This is because FRISIA would aggregate segment level data, but probability distributions of storm surge levels are not meaningful at a high level of aggregation. Therefore, our approach is to sum up the generally susceptible, the annually exposed, and the fully inundated coastal assets and population from each segment in a coastal zone respectively, expressed as fractions of the overall coastal stocks. This is done in a pre-processing step that calculates these fractions for each GMSL data point from the SSP5-8.5 scenario until 2200, in order to find relationships between these fractions and a maximum possible range of GMSL values that is relevant for FRISIA. We use a high emissions scenario, rather than a simple array of possible GMSL values, in order to attain realistic values for local SLR for, both, the aggregated coastal zone and each coastal segment. This means for a given “regional-mean” sea level (RMSL) rise within a coastal zone, the corresponding local SLR is used to calculate the above mentioned fractions within a segment. This is where the DIVA database is used again. DIVA provides 15 segment-level area parameters that can be used in the following functional form, as in the CIAM model, to calculate the inundated area for a given increase in local sea level:

sl in this equation is the local SLR for each segment, when calculating inundated fractions, but it is local SLR plus the height of a 1000-year return period storm surge in this segment, when calculating the generally susceptible area. We add this surge height, which is the highest surge level in DIVA, to get the maximum area that could possible be susceptible to storm surges. For both, the calculated area in each segment is set to zero, if the local SLR is smaller than the flood protection height H in the segment, so that no flooding would occur. The inundated area can then be combined with the segments' population density and GDP per capita data to calculate the fully inundated fractions of people and assets for each level of local SLR in each segment, assuming an even distribution within the segment.

The same approach is used for calculating the people and asset fractions that are annually exposed to temporary flooding, that is, storm surges. For this, we use the following formulation of the CIAM model that calculates annual exposure area based on segment-level return periods and local SLR for each segment (sl):

The parameters A, B, c and σ0 are available for each segment from the CIAM model repository. Again, population density and GDP per capita data are used to turn area into exposed population and assets.

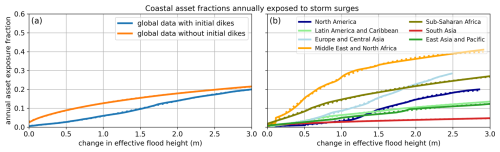

The segment-level data for annual exposure and general susceptibility to storm surges, as well as inundated assets, people and land are then summed up over all segments that constitute a coastal zone in FRISIA and divided by the overall amount of people and assets in that coastal zone (except for inundated area, which is used in absolute terms). For each coastal zone, these variables can then be expressed as a function of the mean “effective flood height” in that coastal zone, as it is shown in Fig. 3 for the annual asset exposure to storm surge damages. The effective flood height S is thereby simply the mismatch between the current RMSL anomaly in that coastal zone and the increase of the flood protection height since the beginning of the integration at t0:

i.e. it is a measure of how much the protection level changed relative to the initial level. This follows the simple assumption that an increase in flood protection height can fully balance any equivalent level of RMSL rise. We note that the current version of FRISIAv1.0 might therefore underestimate damages in mixed scenarios, in which flood protection height is increased, but this increase cannot keep up with RMSL rise. This does not affect the standard experiments presented in this manuscript.

As the aggregation of data is done in a pre-processing step, we continue to express the aggregated data in a functional form, in order to be able to load and use them in FRISIA, as shown exemplary in Fig. 3 for coastal asset exposure. Logistic functions are used to parametrize the data, if the initial dike height from the DIVA dataset is taken into account (blue line in Fig. 3a). A logarithmic function is used in the counterfactual reference scenarios without initial flood protection (orange line in Fig. 3a) that we use in Sect. 4.2 for comparison to CIAM. The functional representation of storm surge exposure is in fact the main determinant of how future damages of SLR evolve in the case of no adaptation. From the blue line in Fig. 3a it can be seen that the global annual storm surge exposure of assets is roughly a linear function of the effective flood height, and hence GMSL rise. However, Fig. 3b shows that there is a big spread in how the exposure in different regions responds to RMSL rise, which means that simple linear relationships between GMSL rise and coastal damages will fail when extrapolated beyond a global aggregation level.

Figure 3The fraction of the original asset distribution that is annually exposed to storm surges, , as a function of changes in the effective flood height S. (a) Data from the global aggregation setup for the cases of including and not including the initial dike height from the DIVA dataset. (b) Data of the regional aggregation setup, when including the initial dikes. The solid lines are the aggregated data from the CIAM exposure estimation and the dotted lines are the fits used to represent this information in FRISIA.

As a consequence of our highly aggregated modelling approach, our representation of coastal flooding is a major simplification of reality, as it does not incorporate any detailed information on coastal morphology, shoreline type or local wave heights, which would be necessary to explicitly model impacts of SLR at the local scale. This is a limitation of our modelling approach, which we discuss further in Sect. 7, but highlight here that the same simplifications are made in CIAM, which is more disaggregated than FRISIA, and that representations of SLR impacts in IAMs are typically far less complex.

3.2.3 Coastal protection

We follow the CIAM model in its formulation of coastal protection and track an aggregated flood protection height H as the only form of generalised protection against rising sea levels. This simple approach is necessary, because the most suitable form of flood protection is highly dependent on local boundary conditions, which are not tracked in the model. The initial flood protection height H0 is taken as the mean dike height from the DIVA data set, averaged globally or for each region depending on the aggregation level. The total cost of coastal protection is comprised of three components: the cost of raising flood defenses, maintaining them, and the opportunity cost of the land used for building them.

The cost to raise flood protection further by ΔH is calculated, as in CIAM, as

where L is the flood protection length. The construction cost cconstruct is defined as the product of a reference construction cost of 0.00602 (0.005–0.007, upper and lower parameter bounds) (USD 2010 billion) km−1 m−2 as in CIAM, and a construction cost index (cci) that depends on GDP per capita in the coastal zone. The cci formulation is fitted with a linear function to the cci data from the CIAM repository (taken from the World Bank Group, 2017 International Comparison Program (ICP); updated compared to Wong et al., 2022), and country-level estimates of GDP per capita. Like in CIAM, values for the cci are limited between 0.5 and 2.5, to avoid unrealistic construction costs (Wong et al., 2022).

Maintenance costs for the raised flood protection are tracked as

with fmaintain=0.02 (0.015–0.03) being the fraction of construction costs that are required annually for maintenance (Diaz, 2016). When calculating the total SLR adaptation costs, we subtract from the total costs of maintenance the costs that would occur if the flood protection height was not changed from its initial height H0. This is done to track only those adaptation costs that are induced by SLR and not by increased construction costs. We point out that in our approach the simulated construction of flood protection only tracks what would be constructed in response to SLR. Hence, the assumption is that the initial protection levels at the start of the integration period are maintained; we follow this approach because we are only interested in the additional costs attributable to SLR under climate change.

A third cost component is the opportunity cost of using the land for flood protection, calculated as in CIAM

where the factor 1.7 comes from the ratio of sea wall width over height (Diaz, 2016). The land value lv is defined using an initial average land value of 0.005376 (0.005–0.006) (USD 2010 billion) km−2 (Darwin, 1995; Wong et al., 2022). The land value grows over time, depending on demand and willingness to pay, which can be approximated as a function of coastal GDP per capita and population (Yohe et al., 1999). This is how it is applied in the CIAM model (Diaz, 2016), and we follow this approach. The annual opportunity cost rate of land is yr−1 (Wong et al., 2022).

There is some loss of information going from CIAM to FRISIA in this instance, because of the necessary aggregation across all segments. The most important issue is that the required flood protection investment is quadratic in height. Using the mean flood protection height over all segments in a coastal zone therefore means that calculated costs are not exactly equal to those in CIAM, given that everything else would be the same. However, most other formulations are linear, and the fact that there is only one type of flood protection, the cost of which are proportional in coastline length, means that the CIAM formulations are generally also useful in FRISIA.

The annual amount of money that is invested into flood protection is derived from the theoretical investment needed to restore and maintain the initial protection level under current and expected SLR over the next 50 years. We choose a time horizon of 50 years, because, on the one hand, this gives enough time for building sufficient protection, while, on the other hand, there is still a relative small uncertainty in SLR projections over 50 years compared to the high uncertainty over longer time scales (see Fig. 1). In general, this follows the assumption that coastal zones, which adapt to SLR by building flood protection, will do so not just in response to experiencing changes in sea level, but using their knowledge about future SLR.

However, as the original purpose of FRISIA is to be run coupled to an IAM, which interactively provides the drivers for annual rates of GMSL rise, it will not always have access to pre-computed time series that provide the actually modelled GMSL rise in 50 years. Instead, we calculate the expected GMSL rise over the next 50 years, SLR50, using a fitted linear relationship depending on the current GSAT anomaly and CO2 emissions. This relationship was derived using the model of GMSL presented in this manuscript, and it gives an estimate that is very close to the actually modelled GMSL rise in 50 years (Fig. B8). While this relationship was fitted using data of GMSL, the expected RMSL for each coastal zone can be calculated using the pre-computed weights for each coastal zone, which is provided as pre-processed input as described in Sect. 3.2.1. We note that this assumes that the relative contribution of the individual SLR processes stays approximately the same as in the projection used for the fit (SSP5-8.5). Furthermore, the fit was purposely done without activating the possibility of high impact processes on the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheet contributing to GMSL rise, indicating that the expected GMSL rise will underestimate the actual GMSL rise in 50 years if the high impact switch is activated when running the model.

The expected SLR over the next 50 years is then used together with the current effective flood height, S, to compute the required additional flood protection height. The required investment to maintain the initial protection level then is

The actual annual investment in flood protection I is further modified from I50, first using a scale parameter Wprotect with values between 0 and 1, which can be interpreted as the political will to invest in flood protection. Next, the total investment is divided by the time it takes to build flood protection τprotect, which we assume to be 10 (5–25) years, as in CIAM (Wong et al., 2022). Finally, we calculate the maximum amount of money available annually for flood protection as a constant fraction of the coastal GDP, finvest, which has to also cover flood protection maintenance costs. The actual annual investment is therefore

and it is directly transformed into an increased flood protection height in the next time step. As CIAM does not include such a limit on flood protection spending, we deactivate this limit in our comparison to CIAM results as well. The limit is activated during the respective feedback analysis and the simulations coupled to an IAM.

3.2.4 Coastal assets

FRISIA tracks a stock of coastal assets that is initialised by calculating coastal GDP from population density (taken from DIVA) and country-level GDP per capita data, following the SSP scenarios (Riahi et al., 2017; Cuaresma, 2017). We further follow CIAM (Diaz, 2016) and assume a constant asset to GDP ratio of 3 (Nordhaus, 2010). This means that asset stocks in FRISIA are a broadly defined representation of the total value of past investments that produce economic output, after accounting for depreciation. This includes, but is not limited to, residential and non-residential buildings, infrastructure, equipment and machinery (Samuelson and Nordhaus, 2001). There is no disaggregation of assets and no relative weighting by their vulnerability to SLR. Coastal assets can be increased or reduced via four different pathways.

-

Asset growth. Asset values grow at a rate rA that is either the coastal GDP growth rate, assuming a constant future asset to GDP ratio (Nordhaus, 2010; Diaz, 2016), or directly using an asset growth rate, if this is provided by the IAM. In addition, in FRISIA the asset growth can be reduced if the expected effective flood height in 50 years, S50, is growing. This reflects reduced investment and asset value reductions under increased future storm damage risk. A feedback of SLR exposure on asset prices has been reported in some studies in terms of a discount on real estate prices in exposed areas (Bin et al., 2011; McAlpine and Porter, 2018; Bernstein et al., 2019; Keys and Mulder, 2020; Tyndall, 2023); we refer to Contat et al. (2024) for a recent review. We here assume that this effect will grow with increased exposure to SLR, and that it affects all types of assets. We calculate the expected effective flood height using the expected SLR over the next 50 years and the potential increase of the flood protection height ΔH50, which is the height increase under a continuation of the current annual investment in flood protection. Together this gives

We then use the expected effective flood height to reduce asset growth by the likelihood of investment

where S50,halfpoint is the expected future effective flood height at which only half of the investment would be made. We use S50,halfpoint as the uncertainty parameter in this formulation with a large range of allowed values (0.5–3.0 m), because of the large uncertainty around the effect of SLR on asset prices (Contat et al., 2024). If , the change of asset values A due to GDP growth is

but if ρ≥ρthreshold the growth rate is not affected by the likelihood parameter. The likelihood threshold ρthreshold is used to distinguish between well protected and poorly protected coastal zones. This is important as we assume that the amount of asset growth that is removed due to reduced investment is not completely lost from all coastal zones, but might be invested into other, better protected, coastal zones, which is reflected by the parameter λ. We crudely assume that 50±30 % of investments are preferably made in the coastal zone, so that this part of the removed growth from badly protected coastal zones is actually moved to coastal zones with ρ≥ρthreshold, weighted by their relative assets fraction. If there are no such coastal zones, or if the model is used in global mode, i.e. with just one global coastal zone, the coast-specific part of removed growth is added back to the badly protected coastal zones, under the assumption that investment will then be made regardless of the risk. Even though this is a stylized implementation of human behaviour, it still represents a significant step forward from the typical assumption that there is no feedback from expected SLR exposure to asset growth in the coastal zone that is typically used in IAMs. Nevertheless, the reduction of asset growth in coastal zones with expected increasing flood risk is turned off in our comparison to CIAM, as this is a hypothetical behaviour that is not captured by CIAM.

-

SLR-driven storm surge damages. The increase of storm surge damages under rising sea levels is conceivably the main component of the overall costs of SLR in a scenario of no adaptation against SLR (Wong et al., 2022). FRISIA calculates the fraction of the original coastal asset distribution that is generally susceptible to storm surge damages, , as well as the respective fraction of assets that experiences storm surge damages in a given year, , as functions of the effective flood height S that were fitted to CIAM data of annual storm surge exposure (Fig. 3). From the latter, the difference between the current and the initial exposure fraction is used to only account for storm surge damages that are driven by SLR. Furthermore, the asset fraction that is already removed from the coastal zone by forced or planned retreat, , is taken into account to calculate the actually exposed asset fraction in a given year (a feature that is not accounted for by CIAM). The overall annual storm surge damage is then

where the flood damage resilience R is a function of GDP per capita as in CIAM, accounting for the fact that wealthier coastal zones are more resilient to damages (Diaz, 2016). We further added the factor , which is the maximum fraction of exposed asset values that can be destroyed in a storm surge at zero resilience. This parameter is used to calibrate our results against CIAM output of storm surge damages.

While the standard assumption in most existing SLR impact models is that these damages do not impact the evolution of coastal assets, there is growing evidence for lasting reductions at least in real-estate values after major storm surge events (e.g. Fisher and Rutledge, 2021; Addoum et al., 2024; Holtermans et al., 2024); see Contat et al. (2024) for a recent review. Adding to this is the possibility that firms might not rebuilt or further invest into damaged company sites due to the potential of future flooding, we introduce a very simple formulation in which only a fraction (0.75–1.0) of damaged assets is repaired. The actual reduction of coastal asset values then becomes

In the reference setup without additional feedback, which we use to compare FRISIA to CIAM, we set the repaired fraction frepair=1, so that storm surge damages are not reducing coastal asset values. We further explore the consequences of setting frepair<1 in Sect. 5.1.

-

Planned retreat. The formulation of planned retreat of assets uses the expected effective flood height in 50 years to calculate the expected future susceptible asset fraction, using the same fitted function as for calculating . Furthermore, just as for the protection decision, we use a scale parameter Wretreat, which can be seen as the population's will to retreat under expected storm surge exposure. Assets can conduct planned retreat if they will generally be susceptible to storm surges in the future, as owners will try to reduce future damages from SLR. This is a strong form of retreat that is comparable to a retreat behind the 1 in 1000 year storm surge height in CIAM. The change to coastal assets because of planned retreat is

where τretreat=10 (5–25) years is the proactive retreat time scale of coastal assets.

-

Forced retreat. this form of retreat occurs for assets that are becoming inundated because of sea level rise. We calculate the inundated asset fraction , similar to the susceptible and exposed fractions, via a logistic function fitted to DIVA data. The change of the coastal asset stock due to forced retreat then amounts to

again taking into account the asset fraction that was already removed in previous time steps . Hence, when planned retreat was already undertaken, , and the forced retreat is zero. In reality, asset values would be reduced earlier than modelled here via the depreciation of assets that are to become inundated. Therefore, the modelled reduction in the asset stock is lagging behind what would occur in a more complex model that incorporates this depreciation, but the final value over long time scales is ultimately the same.

3.2.5 Coastal population

FRISIA tracks a stock of coastal population that develops independently of the stock of coastal assets. Nevertheless, changes in coastal assets and population are driven by the same general processes, with just minor differences in parameterization. The coastal population stock is initialised with population data from each coastal segment, taken from the DIVA dataset (Vafeidis et al., 2008). Coastal population, P, then grows with a global or regional coastal growth rate, which is provided by the IAM, or prescribed externally when the model is run uncoupled:

Unlike in the case of assets, we do not assume a possible reduction in this growth rate under expected increased future flood exposure, and it should be noted that the population growth can become negative in the future.

The population fraction that is generally susceptible and the fraction that is annually exposed to storm surges are both calculated from a logistic function fitted to DIVA and CIAM data, using the same method as the respective asset fraction (Fig. 3). The number of people exposed to storm surges because of SLR, Pexposed, is calculated similarly to asset storm surge damages:

Again, we use the difference between the current and the initial exposure fraction of people to only track the SLR-driven number of exposed people. The change in the coastal population stock due to storm surges equals the number of fatalities in storm surges

The fatality fraction ffatality=0.01 (0.005–0.02) of people exposed to storm surges is the same as in CIAM and R is the same resilience as for the damage to coastal assets. While CIAM has the same fatality rate, flood fatalities do not feed back to the population density in CIAM.

Planned and forced population retreat are handled in exactly the same way as retreat of assets:

This uses the same retreat time scale and scale parameter as for the retreat of assets.

4.1 Cost formulation

We define the costs and damages of sea level rise principally in the same way as Wong et al. (2022). However, we do not translate the loss of life into a cost, but rather compare the number of annual storm surge fatalities between the models. When FRISIA is coupled to an IAM the loss of life can feed into the integrated population model, and be counted as part of the loss of life due to climate impacts. Apart from that, there are four different types of costs:

-

The costs of protecting against SLR, which are defined as the sum of the costs to construct new flood protection, the costs to maintain the additional flood protection and the opportunity costs of the land lost for the new flood protection, which are defined in Sect. 3.2.3.

-

The costs of storm surge damages Dstorm, as defined in Sect. 3.2.4 (Eq. 13).

-

The cost to relocate people and assets, Costrelocate, which is based on the people and assets that retreat annually. The total costs consist of three sub-costs, and all our cost formulations are in line with assumptions made in CIAM, except that we added uncertainty ranges to better capture the parametric uncertainty. First, there is the cost to relocate people, which for people who are conducting a planned retreat is the average annual income per person and is times as much for people that are forced to retreat (CIAM applies a constant increase factor of 5, noting that this parameter, as well as the following ones, lack an empirical basis, see supplementary material in Diaz (2016). Lincke and Hinkel (2021, supporting information Table S4) reviews literature values ranging from 2.3 to 9.5). Second, there is the cost to demolish the abandoned immobile part of the assets, and these demolition costs are assumed to be of the immobile part of asset values. Third, there is the cost to relocate the mobile part of assets. We assume the mobile fraction of coastal assets to be . The cost to relocate the mobile assets is assumed to be a fraction of the retreating asset values, .

-

The total cost of flooding is the sum of the value of the abandoned immobile part of coastal assets and the opportunity costs of the land that is lost to the sea. We assume that under planned retreat a large part of the immobile assets is depreciated at the time of retreat, so that only a small fraction of those assets, , contributes to the costs of flooding. Under forced retreat, the full immobile asset values are lost and contribute to this cost.

A logistic function that is fitted to DIVA data is thereby used to calculate the area of the land that is inundated or abandoned in the case of retreat, as described in Sect. 3.2.2.

The costs of wetland losses are not included in FRISIA. We have left this scope for future development because the current generation of IAMs is unable to make use of this information. Furthermore, we note that, just like CIAM, our model does not capture the effect of SLR on economies that interact with the coastal environment, like fisheries, tourism or international trade. There is insufficient information available to appropriately calibrate and represent the indirect impacts of SLR on coastal industries. These costs are only partly represented via their relationship to coastal GDP and hence asset values, so that the calculated costs in FRISIAv1.0 are potentially underestimated.

4.2 CIAM comparison

For the evaluation of the model, we set up FRISIA as close as possible to the CIAM setup presented in Wong et al. (2022). The simulations start in the year 2010 and integrate with a time step of one year until the year 2150. The population and asset stocks are initialised from SSP and DIVA data as described in the sections above. We note that the data assume a growth rate of zero for assets and population after 2100, which is the same as in Wong et al. (2022), because the long-term socio-economic evolution is very uncertain. This continuation with constant population and GDP leads to a visible kink in the time series, and the form of data continuation needs to be considered when interpreting the results. Furthermore, it should be noted that CIAM integrates with a time step of ten years and costs are partly spread over the 40–50 year adaptation periods (Wong et al., 2022). This makes a direct comparison to FRISIA ambiguous, as FRISIA calculates with a one year time step, and costs are calculated for each year individually. Nevertheless, a more general comparison that focuses on the temporal evolution and the broad range of individual costs is still useful. We note that CIAM and FRISIA will produce different results not only due to differences in level of aggregation but also due to structural changes introduced in FRISIA like the use of the small time step and differently spreading costs over time. Lastly, we run the model for the same SSP scenarios and use the same prescribed (non-optimized) adaptation strategies as presented in Wong et al. (2022). Namely, we run the SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios (Riahi et al., 2017) and apply three different adaptation strategies: No Adaptation, Protect and Retreat.

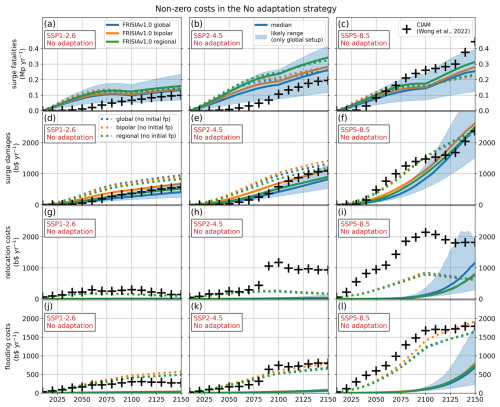

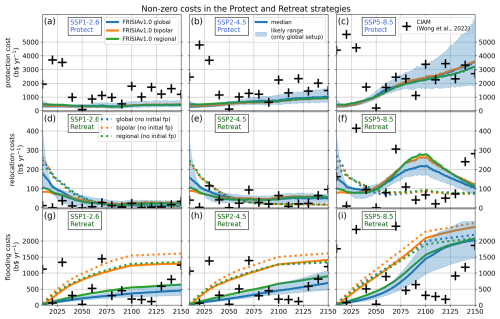

Figure 4 shows the costs for the No Adaptation strategy, while Fig. 5 displays the costs of the Protect and Retreat strategies. For each strategy, only the relevant non-zero costs are plotted. It should be noted that, despite having the same adaptation strategies in both models, there are some inherent differences between FRISIA and the CIAM setup in Wong et al. (2022). First, Wong et al. (2022) initialise the model with the respective adaptation strategy in the first time step. This means that for the No Adaptation strategy, their model assumes that there are no dikes or other forms of flood protection, or that for a Retreat strategy, assets and population have retreated above the height of a storm surge with a specific return period. In contrast to that, we do not recalculate the initial retreat or protect level, but directly use the DIVA data for model initialisation, including an initial flood protection. This means FRISIA by default includes an initial flood protection even when applying the No Adaptation or Retreat strategies, which stands in contrast to what is done in Wong et al. (2022). Therefore, for the comparison in this section, we add another setup of FRISIA, in which there is no initial flood protection. The simulations using this setup are represented by the dotted lines in Figs. 4 and 5. Structurally, the main difference to the standard FRISIA setup is that the model now responds differently to increasing sea levels, represented by the fitted functions for how the asset's and population's annual exposure and susceptibility fractions behave as a function of the effective flood height. In order to then calculate just those costs that are induced by SLR, we subtract the initial storm surge exposure from the current exposure in the storm surge damage calculation. Second, CIAM allows for decisions to retreat or protect against storm surge heights with different return periods of 1, 10, 100 or 1000 years. We do not incorporate that level of detail, but rather include the parameters Wprotect and Wretreat, which can be varied between zero and one. A value of one thereby indicates a desired perfect protection against any SLR-driven damages in the Protect case and a retreat to the 1000 year maximum storm surge height in the Retreat case. Hence, the results depicted in Fig. 5 show data from the maximum possible Retreat or Protect strategies for both CIAM and FRISIA. For each adaptation strategy, scenario and ensemble member, the FRISIA model was run in three setups with different levels of aggregation: a global model, a bipolar model, and a regional model (see Sect. 3.2.1 and Table B2) in the Appendix.

Figure 4The global costs of sea level rise in the No Adaptation strategy. Data from CIAM (Wong et al., 2022) are compared to output from FRISIA for different levels of aggregation. Shown are results for the scenarios SSP1-2.6 (left), SSP2-4.5 (middle) and SSP5-8.5 (right). The solid lines represent model runs with an initial flood protection height as taken from the DIVA dataset, whereas the dotted lines are the same simulations with an initial flood protection height of zero, as in CIAM. The shaded area represents the 17th–83rd percentile range from the global FRISIA setup with initial flood protection.

Figure 5The global costs of sea level rise in the Protect (a–c) and Retreat (d–i) adaptation strategies. All figure settings are as in Fig. 4. Only the non-zero costs are shown, so for example in the “Protect” scenario, there are no storm surge damages or fatalities.

In the No Adaptation strategy, global damages in FRISIA are primarily driven by increasing storm surge damages to population and assets, while relocation and flooding (inundation) costs become relevant only in the 22nd century. In contrast to that, all costs are of a similar importance in CIAM, mostly because there is no initial flood protection at all, so that land becomes inundated and people and assets have to be relocated much earlier. This fits well with our additional experiments without any initial flood protection in FRISIA, which are depicted as the dotted lines in Fig. 4. In these runs, FRISIA relocation and flooding costs are very similar to those in CIAM, but generally a bit lower in the later part of the simulation. Especially, relocation costs are much lower in FRISIA in SSP5-8.5 and after 2090 in SSP2-4.5, but there is no single driver that can explain those differences between the models. One aspect is that the SLR model used in Wong et al. (2022) produces GMSL projections that are higher than the ones in FRISIA by some 10 cm in 2100. Another might be the specific way that costs are aggregated over time in CIAM. We note that the projections from FRISIA draw a more consistent picture in terms of the temporal evolution of costs. After all, the setup with no initial flood protection is a counterfactual scenario.

Similarly, storm surge damages are higher in the early part of the simulation without initial flood protection. This is because in this simulation all parts of the coastal zone will experience early damages from SLR. However, the damages then grow slower, because the additional effect that the initial flood protection can be breached in the future is missing. For the remaining part of the discussion, we stick to the results of the FRISIA setups that do include the initial flood protection, under the assumption that existing dikes will be maintained even in a No Adaptation strategy.

The time series of SLR-driven storm surge fatalities shows a visible kink and faster increase after 2100, while storm surge damages to assets do not show this behaviour. The reason for the kink is the continuation of input data with constant values as described above. But what is the driver of the change in behaviour? The global coastal population is decreasing before 2100, while GDP increases. This leads to a decreasing number of people being potentially susceptible, and, at the same time, an increase of the resilience to damages due to a higher GDP per capita. Both trends counteract the increase of storm surge fatalities due to SLR. After 2100, these trends stop so that the remaining driver is the increase of storm surge fatalities from SLR. The difference for assets is that before 2100 damages are already accelerating, driven by SLR and the increase of asset values with GDP. After 2100 the continuation with constant values slows down the increase of asset values, but also storm surge resilience ceases to increase. Hence, there is no visible change in the evolution of storm surge damage to assets, despite a substantial change in the underlying socio-economic dynamics.

The costs of protecting against SLR are generally the same order of magnitude in FRISIA and CIAM (Fig. 5, top row). The main difference is that there are no jumps in protection costs in FRISIA, as the model simulates more continuous costs than the ten year time step and the adaptation periods in CIAM would allow (the CIAM version presented in Wong et al. (2022) assumes adaptation periods of 40–50 years, starting in 2010, 2050 and 2100, and the flood protection costs are calculated at the start of each adaptation period, assuming that knowledge about future SLR is limited to the end of the adaptation period). The global protection costs are the only relevant costs in the Protect strategy with FRISIA, as the costs of losing wetlands are not calculated in the model. Generally, the total annual protection costs are smaller than the sum of all costs in a No Adaptation strategy at the end of the simulation period, independent of the aggregation level, but flood protection requires investment that is higher than the costs in No Adaptation during the earliest part of the simulation period.

In the Retreat strategy, FRISIA calculates high initial relocation costs because, in the chosen case of maximum retreat, all coastal assets and people retreat to a height where they are not susceptible to storm surges at all. While this is generally the same assumption as in the respective CIAM simulation depicted in Fig. 5, the early relocation costs in CIAM are much smaller, because CIAM assumes an initial state that already follows the chosen adaptation strategy. In FRISIA this adaptation has to happen in the simulation itself, hence there is an initial spike in relocation costs. After this transient behaviour, FRISIA and CIAM calculate similar relocation costs, but the FRISIA projections follow a much smoother curve, because of the reasons discussed above.

Interestingly, FRISIA simulates a peak of relocation costs under the Retreat strategy in 2100, but only for SSP5-8.5 (Fig. 5f). Relocation costs are defined as the costs to move mobile assets and people, and the costs to demolish abandoned immobile assets. These costs are proportional to GDP (assets) and GDP per capita (people), both of which stop to increase after 2100, as a consequence of the chosen continuation method of SSP data beyond that year (compare Fig. B7). This explains one part of why relocation costs stop growing after 2100, and also why the increase of flooding costs slows down in that year (Fig. 5i). However, the question remains why relocation costs increase in SSP5-8.5 between approximately 2030 and 2100, while they remain stable or decrease in the other scenarios. One driver for this is that generally GDP increases a lot faster in SSP5-8.5, where it ends up being almost a factor of two higher in 2100 than in the other scenarios before considering retreat. It also keeps accelerating, while GDP grows more linearly in SSP2-4.5 and growth even decelerates in SSP1-2.6 (this is also a driver of the much faster increase of surge damages in SSP5-8.5 under no adaptation, Fig. 4d–f). The final component necessary to describe the peak shape in relocation costs is the much stronger SLR in SSP5-8.5, which drives the same shape, albeit in weaker form, also in relative terms for asset retreat (not shown). The insight here is that under a strong (expected) SLR many assets that are initially safe because of the currently existing flood protection will become susceptible to storm surge damages in the course of the 21st century and hence retreat. This happens in a relatively short amount of time in SSP5-8.5, while it is more spread in the other scenarios due to slower SLR. The peak shape is therefore also a consequence of including the initial flood protection from the DIVA dataset even in our Retreat strategy simulations, which has not been included in CIAM. Correspondingly, the counter-factual scenario of no initial flood protection (dotted lines), does not show the peak shape, as here assets and people retreat already in the first years of the simulation (at lower costs, but much stronger in relative terms).

The final form of SLR costs, the costs of flooding in the Retreat strategy, are also similar between FRISIA and CIAM, but have less variation in FRISIA. Here, there is a noticeable difference between the three FRISIA setups, where the bipolar setup leads to higher flooding costs, especially in the early years, when SLR is relatively small. The difference between the model versions thereby comes from aggregation errors when converting retreating assets into abandoned land, and these errors are the lowest in the bipolar setup. This issue only affects the opportunity costs of the abandoned land, which do not provide feedback to any other part of FRISIA, and which are also not likely to be useful output in most IAMs. Therefore, we do not act on this dependence. Fixing the problem would require a substantial increase of process detail, and in the current version of the model we put a higher value on dynamic complexity and maintaining model simplicity.

Overall, the presented simulations show that the FRISIA model calculates estimates for the costs of sea level rise that are in line with the projections of the more complex CIAM model (Wong et al., 2022). FRISIA can produce SLR damages and adaptation costs in scenarios of no adaptation, protection or retreat from the coast, and the relevant FRISIA output is largely independent of the level of aggregation.

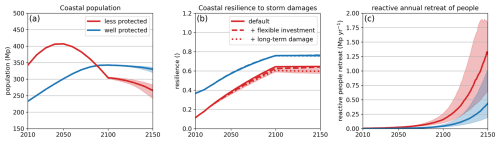

The previous section has shown that the no-feedback version of FRISIAv1.0 can approximate the calculated global costs of SLR impacts and adaptation in CIAM (Wong et al., 2022), when given the same input. In this section, we make use of the non-optimising, flexible model structure of FRISIA, and explore the effect of incorporating additional feedback that could influence the evolution of coastal assets or population, and hence the costs of SLR. For this, we use the bipolar model setup of FRISIA, because its unequal separation of assets and population can lead to heterogeneous dynamics, while still maintaining a high level of aggregation. This makes it more illustrative than the regional setup of FRISIA, in line with the focus of this study being to showcase the capabilities of FRISIA and to understand the dynamics of the coastal zone under rising sea levels. For the same reason, we use the SSP5-8.5 scenario in this section, as it is the most extreme case of SLR.

5.1 Reduced future investments and reparation

CIAM and the no-feedback version of FRISIAv1.0 assume that storm surge damages have no long-term effect on the evolution of coastal assets and are immediately repaired. Furthermore, the structure in CIAM represents the assumption that assets in the coastal zone grow independently of the expected SLR and storm surge exposure, based on the regional GDP growth taken from SSP input data. Here, we explore what happens in the case that both of these effects lead to a reduction in asset values or their growth rate under the No Adaptation strategy. The underlying philosophy of the new feedbacks has been laid out in Sect. 3.2.4. To implement these effects, the evolution of coastal GDP is made dependent on the evolution of coastal assets in all scenarios presented from this point forward. A relative reduction in coastal asset values compared to the coastal population will now reduce the average GDP per capita in the coastal zone, and thereby reduce the coastal resilience to storm surge damages in the future. From this point forwards, all scenarios also include the effect that asset loss through inundation reduces the fraction of assets annually exposed to storm surges.

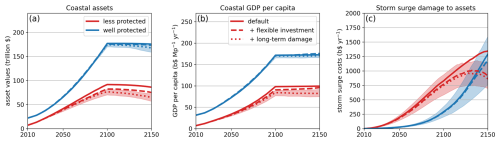

If a coastal zone expects an increase in exposure to storm surge damages in the future, that is S50>0 in FRISIA, it is conceivable that there will be less investment into the respective coastal zone. FRISIA makes the simplifying, but reasonable, assumption that asset growth is a form of investment, therefore, incorporating this behavioural feedback translates into a reduction in the annual growth of asset values, as reflected in Eqs. (11) and (12). Furthermore, within FRISIA we assume that some of the growth reduction is actually moved to coastal zones that retain a low exposure to storm surge damages. The effect of incorporating this feedback is reflected by the difference between the solid and the dashed curves in Fig. 6 (additional time series of variables can be found in Fig. B9). In the bipolar aggregation setup of FRISIA, by definition, all assets in the less protected coastal zones, but none in the well protected coastal zones, are initially susceptible to storm surge damages. Hence, this mainly affects less protected coastal zones, in which coastal asset values are reduced by 11.2 (6.4–15.6) % in 2150 compared to the baseline version without this feedback. The reduction in asset values then leads to smaller storm surge damages in the future, as there are less assets in the future. Because of this feedback, FRISIA simulates a peak in the SLR-driven storm surge damages in the first half of the 22nd century in less protected coastal zones. At the same time, a small part of the asset growth is moved from the less protected to the well protected coastal zone, slightly increasing the coastal asset values there. Therefore, activating the investment feedback has almost no effect on well protected coastal zones during the simulated period.

Figure 6The effect of asset feedbacks on the evolution of coastal asset values (a), GDP per capita (b) and annual storm surge damages (c) for the No Adaptation strategy in the bipolar setup. Shown are the median values of the no-feedback case presented in Sect. 4, and two cases with additional feedbacks as described in the text. The shaded areas represent the 17th–83rd percentile range of the final setup only, as showing all uncertainty ranges would obscure the figure. All input data are from SSP5-8.5. We point out again that the almost constant evolution of coastal assets and GDP per capita after 2100 is because the reference GDP and population data from the SSP scenario are continued with constant values after that year.

A peak of SLR damages in the first half of the 22nd century has also been simulated in the model of Desmet et al. (2021). They use a dynamic spatial economic model that allows capital and people to move to other locations, in search of the most economically efficient adaptation. Although they use a much more sophisticated economic model, this is in principle a similar feedback as simulated with our approximated simple reduction in the growth of coastal assets, resulting in the qualitative peak and decline shape of SLR damages. These results underline the importance of including migration into studies of SLR impacts.

Similar to a potential reduction in the growth of coastal assets, it is also possible that assets that have been damaged in a storm surge are not repaired. As a form of adaptation, some of the damaged assets might be rebuilt away from the coast, or not repaired at all. In this case, storm surge damages would actually reduce coastal asset values, effectively reducing coastal GDP and hence the resilience to storm surge damages in the future. The dotted line in Fig. 6 shows what happens if this feedback is activated in addition to the feedback described above. Again, the less protected coastal zones are the areas most affected. In these zones, coastal asset values are reduced by an additional 11.5 (4.3–21.7) % at the end of the simulation period, under a No Adaptation strategy and compared to the previous discussed case, where only the investment feedback is included. In the well protected coastal zone, the resulting coastal asset value reduction is just about 2.5 (1.0–6.1) %, because the SLR-driven storm surge damage is generally smaller in the early simulation period. The asset value reduction also leads to a reduction in future storm surge damages in the less protected coastal zone, as the amount of assets that can be damaged is lower. However, this reduction is smaller than what could be expected from the corresponding reduction in asset values, and there is no reduction in storm surge damages in the well protected coastal zone at all. This is a consequence of the reduced GDP per capita in the coastal zone, which leads to a reduction in resilience against storm surge damages.

Both of the above discussed feedbacks lead to a reduction in coastal assets and GDP, which, on the one hand, reduces the future storm surge damage potential, but, on the other hand, also reduces the resilience of the coastal zone against storm surge damages. We highlight that there is also a process that leads to the opposite effect, which is migration towards the coast or further urbanisation of coastal cities. Including coastal migration would increase coastal asset values and population, leading to potentially larger damages in the future. But whether coastal migration increases or decreases coastal GDP per capita will depend on the relative ratio of the growth rates. This effect is not fully included yet, as the growth rates of coastal assets and population are aggregated from country-level data, which do not account for relative changes in the asset and population distributions within a country. Incorporating coastal migration is therefore an interesting potential future application of FRISIA.

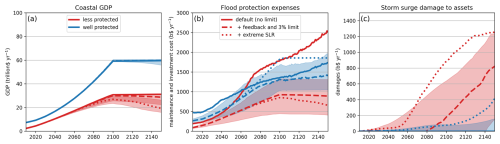

5.2 Failing to protect

So far, the Protect strategy in FRISIA allowed for unlimited investment into flood protection, neglecting the possibility that there is not enough money available. Here, we add a simple limit that annual flood protection spending is limited to 1 %–5 % of the coastal GDP (finvest in Eq. 9). For completeness, we also include the previously introduced investment and storm surge damage feedbacks.

The difference between the solid and the dashed lines in Fig. 7 represents the impact of the flood protection investment limit. Now, in the early years, both, well and less protected coastal zones cannot invest the desired amount of money into flood protection. However, this does not lead to the emergence of SLR-driven storm surge damages in well protected coastal zones, as even the reduced investment leads to sufficient increases in the flood protection height that are ahead of increases in sea level. This is not the case for the less protected coastal zone, so that SLR-driven storm surge damages emerge around the year 2070. This then leads to a relative reduction in coastal asset values and GDP, limiting the available money for future flood protection investments even further. This process represents a positive feedback loop, in which less protected coastal zones do not have enough money for full protection, leading to future SLR-driven damages that reduce the available amount of money even further.

Figure 7The effects of limiting flood protection spending and extreme SLR on the evolution of coastal GDP (a), flood protection expenses (b) and annual storm surge damages (c) for the Protect strategy in the bipolar setup. Shown are the median lines of three scenarios: (1) the no-feedback case presented in Sect. 4 (solid lines). (2) A scenario with the additional feedbacks from Fig. 6 and a flood protection spending limit as a percentage of coastal GDP (dashed) (3) A scenario of extreme SLR with settings as in the previous scenario (dotted). All input data are from SSP5-8.5. The shaded areas represent the 17th–83rd percentile range of scenario 2, as showing all uncertainty ranges would obscure the figure.