the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Operational numerical weather prediction with ICON on GPUs (version 2024.10)

Xavier Lapillonne

Daniel Hupp

Fabian Gessler

André Walser

Andreas Pauling

Annika Lauber

Benjamin Cumming

Carlos Osuna

Christoph Müller

Claire Merker

Daniel Leuenberger

David Leutwyler

Dmitry Alexeev

Gabriel Vollenweider

Guillaume Van Parys

Jonas Jucker

Lukas Jansing

Marco Arpagaus

Marco Induni

Marek Jacob

Matthias Kraushaar

Michael Jähn

Mikael Stellio

Oliver Fuhrer

Petra Baumann

Philippe Steiner

Pirmin Kaufmann

Remo Dietlicher

Ralf Müller

Sergey Kosukhin

Thomas C. Schulthess

Ulrich Schättler

Victoria Cherkas

William Sawyer

Numerical weather prediction and climate models require continuous adaptation to take advantage of advances in high-performance computing hardware. This paper presents the port of the ICON model to GPUs using OpenACC compiler directives for numerical weather prediction applications. In the context of an end-to-end operational forecast application, we adopted a full-port strategy: the entire workflow, from physical parameterizations to data assimilation, was analyzed and ported to GPUs as needed. Performance tuning and mixed-precision optimization yield a 5.5× speed-up compared to the CPU baseline in a socket-to-socket comparison. The ported ICON model meets strict requirements for time-to-solution and meteorological quality, in order for MeteoSwiss to be the first national weather service to run ICON operationally on GPUs with its ICON-CH1-EPS and ICON-CH2-EPS ensemble forecasting systems. We discuss key performance strategies, operational challenges, and the broader implications of transitioning community models to GPU-based platforms.

- Article

(2208 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Numerical weather prediction (NWP) plays a critical role in our society, supporting applications ranging from renewable energy management to the protection of life and property during severe weather events. The growing demand for accurate weather forecasts requires the use of advanced computational techniques to improve the performance of NWP models. With greater computing power, models can run at higher resolutions, capturing finer-scale atmospheric processes and local weather phenomena that coarser models cannot resolve (Palmer, 2014; Bauer et al., 2015). This could improve the accuracy of predictions for severe weather events such as thunderstorms, hurricanes, and heavy rainfall. Furthermore, greater computational power allows for more frequent updates and the execution of larger ensemble forecasts, thereby enhancing forecast reliability through quantification of uncertainty. In recent years, graphics processing units (GPUs) have emerged as a cornerstone of high-performance computing (HPC), offering high throughput and improved energy efficiency through massive parallelism. However, in order to benefit from the latest advancements in HPC technology, weather and climate models must be adapted to operate effectively on this hardware. Furthermore in the context of emerging machine learning for weather forecasting having a GPU capable model is of great interest since both the Machine Learning algorithms as well as the traditional NWP model can run on the same GPU hardware allowing for synergies in terms of system investment.

Weather and climate models are typically large community codes comprising millions of lines of Fortran or C/C code. Adapting such a large code base to GPUs requires significant effort. While many attempts have been made to port individual components, only a handful of these models have been fully ported and are being used in production on GPU-based or hybrid systems. Different groups have adopted various strategies. Some early work includes the Japanese ASUCA model (Shimokawabe et al., 2011) which has been ported with a CUDA (Nickolls et al., 2008) rewrite. Another approach is to use compiler directives such as OpenACC or OpenMP for accelerators. The advantage of this approach is that it can be incrementally inserted into existing code and may be more easily accepted by the modeling community. The MesoNH (non-hydrostatic mesoscale atmospheric) model was ported to GPUs using such OpenACC compiler directives (Escobar et al., 2024). Other models have or are beeing re-written using a Domain Specific language (DSL) approach, allowing to potentially reach a better performance portability as well as a separation of concerns between the user code and hardware optimizations. The COSMO (Consortium for Small-scale Modeling) model was ported using a combination of DSL rewrite and OpenACC directives, achieving substantial speed-ups on GPU systems with respect to the CPU baseline (Lapillonne and Fuhrer, 2014; Fuhrer et al., 2014). It was also the first model used by a national weather service for operational numerical weather prediction on GPUs. The LFric model developed by the UK MetOffice is using the Psychlone DSL (Adams et al., 2019). Several ongoing effort are considering the GT4py (Grid Tools for python) DSL this includes the Pace model (Dahm et al., 2023) from Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence (AI2), the Portable Model for Multi-Scale Atmospheric Predictions (PMAP) model (Ubbiali et al., 2025) at ECMWF, or the ICON (Icosahedral Nonhydrostatic) model (Dipankar et al., 2025). Recently the Energy Exascale Earth System (E3SM) was entirely rewritten using C and the Kokkos library (Donahue et al., 2024). These diverse efforts highlight the growing necessity of exploiting modern hardware architectures, such as GPUs, to meet the increasing computational demands of weather and climate modeling.

To take advantage of advances in hardware architectures, the ICON (Icosahedral Nonhydrostatic) model (Zängl et al., 2015) – a state-of-the-art model for weather and climate simulations – was first successfully ported to GPU architectures using OpenACC compiler directives which have been applied to the existing Fortran-based code. The initial effort targeted climate applications (Giorgetta et al., 2022), leaving components essential for NWP unported. Building on this foundation, we extend the GPU support to weather applications by porting the missing components using OpenACC directives. Although several other configurations are ported and supported on GPU, this work particularly focuses on the operational setup at the Swiss National Weather Service MeteoSwiss. Our comprehensive approach spans the entire operational workflow, from initialization to output, while meeting stringent time-to-solution requirements of various products such as forecasts for aviation or other NWP-specific applications.

The ICON (Icosahedral Nonhydrostatic) model, by Zängl et al. (2015), is a climate and numerical weather prediction system developed through a partnership involving the German Weather Service (DWD), the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology (MPI-M), the German Climate Computing Center (DKRZ), the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), and the Center for Climate Systems Modeling (C2SM). Besides climate and research applications, ICON is used operationally by the DWD, MeteoSwiss and several national weather services of the COSMO consortium for numerical weather prediction. The model employs an icosahedral grid structure, which divides the globe into triangular cells, providing quasi-uniform resolution and eliminating the pole problem inherent to traditional latitude-longitude grids. This grid structure supports local refinement, enabling higher resolution in areas of interest without compromising global coverage. The model uses a finite-volume discretization method on these triangular cells, ensuring mass conservation and accurate representation of atmospheric dynamics. The coupling between dynamics and physics in ICON follows a split-explicit strategy, where the fast dynamical core is sub-stepped relative to the physics time step, allowing for stable integration while maintaining computational efficiency.

For parallelization, ICON adopts a horizontal domain decomposition strategy, where the computational domain is divided into smaller subdomains distributed across multiple processors. The communication accross nodes is implemented using the Message Passing Interface (MPI) library and the model is scaling well up to thousand nodes (Giorgetta et al., 2022). The vertical discretization in ICON is based on a terrain-following hybrid coordinate system which combines the advantages of pressure-based and height-based coordinates. This system allows for a more accurate representation of the atmospheric boundary layer and better resolution of vertical atmospheric processes, particularly in regions with complex topography such as the Alps.

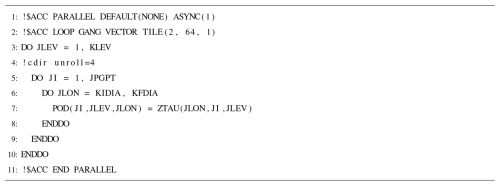

3.1 Overview

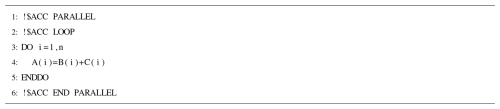

The GPU port of the ICON model is based on OpenACC compiler directives, which are added as comments to the original Fortran source code; see Listing 1. The choice of a directive-based approach was decided over a re-write in a GPU-specific language like CUDA or a DSL, mainly because of its broader acceptance by the ICON community, increasing the chance to re-integrate the work in the main code. In addition, although there is an ongoing project, using the GT4Py DSL to re-write ICON, it was not clear if all features, such as the icosahedral grid, or even if a full re-write could be ready in time for the life cylce of the HPC and operational model at MeteoSwiss. Furthermore the OpenACC directives were chosen over OpenMP for accelerator after an evaluation at the begining of the project showing that the compilers supporting OpenMP were less mature. The OpenACC directives guide the compiler in generating GPU code, reducing the need for manual intervention. A simple code analysis indicates that the ICON model consists of approximately 1.2 million lines of Fortran code, excluding comments and non-executable directives, with an additional 21 000 OpenACC pragmas introduced for GPU acceleration. Restricting the analysis to the subfolders used in operational numerical weather prediction (NWP), it reduces these figures to around 660 000 and 13 000 lines, respectively. One of the key aspects of the port is to reduce data movement between the host CPU and the GPU memory while also maximizing the utilization of the GPU's computational resources.

Listing 1Example of a simple one dimensional loop addition parallelized with OpenACC. The !$ACC PARALLEL indicate the parallel region, while the LOOP statement indicate which loop to parallelized.

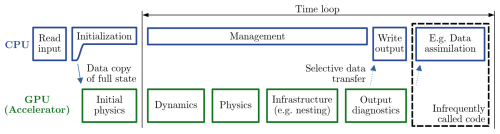

In atmospheric models, the arithmetic intensity, i.e., the ratio of computation (floating-point operations) to memory accesses, is generally low (Adamidis et al., 2025). As a result, only porting isolated kernels to the GPU would incur a significant penalty of data transfer between the CPU and the GPU that cannot be amortized by the ported kernel execution time. Instead, most model components must be ported together, which we refer to as a full port strategy. Timing measurements confirm that transferring all the variables from the CPU to the GPU memory takes approximately as long as performing one full time step on the GPU. To achieve any performance gain using a GPU under these conditions, it is essential that such data transfers are avoided at every time step. Instead, data transfers between CPU and GPU should be limited to infrequent operations, such as writing output to disk. Accordingly, the ICON GPU port is designed such that after the initialization phase on the CPU, all data are copied to the GPU and during the time loop all components called at high temporal frequency are executed on the GPU (Fig. 1). If any code needs to run on the CPU within the time loop, a data copy is added from GPU to CPU.

3.2 Strategy and performance consideration

ICON operates on a three-dimensional computational domain: in the horizontal grid cells are enumerated with a space-filling curve, which is split into nblocks blocks of user-defined block size nproma, while the vertical direction comprises nlev levels. Most arrays in ICON follow the index ordering (nproma, nlev, nblocks), possibly with additional dimensions of limited size. In the GPU port, nproma is set as large as possible, ideally such that all cell grid points of a computational domain, including first and second-level halo points, fit into a single block, yielding nblocks=1. This design choice reduces the complexity of the porting process: parallelization is required only along the nproma and nlev dimensions, while nblock loop can be omitted, since its value is either one or very small. This particularly reduces the call tree size inside a parallel region, since many parameterizations are called inside the block loop. Loops over nproma are usually the innermost loops and rarely contain additional subroutine calls. Although nblocks=1 should not be a requirement from the OpenACC standard point of view, in practice many compiler issues and limitations were circumvented by avoiding calling nested subroutines in accelerated regions. The nproma dimension, with unit stride in memory, is the main direction of fine-grain parallelism and is associated with the OpenACC keyword vector to ensure coalesced memory access.

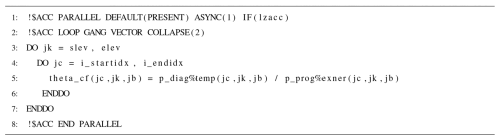

In our porting approach, all components in the time-stepping loop (with minor exceptions) run on the GPU, while components in the initialization run on the CPU (cf. Fig. 1). A challenge arises from the fact that both initialization and time-stepping invoke shared low-level routines. To distinguish between the execution context, an additional logical argument, lacc, is introduced and used as a conditional guard on all parallel and data regions within the shared routines. An example is shown in Listing 2, when the corresponding routine should run on CPU the logical lzacc is set to .FALSE..

Listing 2Example using the lzacc conditional inside a routine in the turbulence component that may be called on the CPU or on the GPU.

The GPU implementation assumes one compute MPI task per GPU. The original communication library is ported to GPU and supports GPU-to-GPU (G2G) communication, enabling efficient data exchange between GPUs during parallel execution. This comprehensive approach to porting ICON to GPUs aims to maximize performance gains and reduce to the minimum data transfer.

3.3 Basic Optimization

Multiple general optimization strategies are considered for the initial GPU port of ICON and are applied throughout the code when possible. The first design choice is to apply ACC LOOP VECTOR to the innermost loop to allow contiguous memory accesses. The inner nproma-loop can be collapsed with the outer nlev loop when appropriate, significantly increasing the amount of available parallelism. This allows to use larger kernel grids that, typically, improves average occupancy and thus helps better hide memory latency.

The second optimization is to merge multiple loops nested together into one large parallel region. This reduces the kernel launch overhead. However, a drawback of this approach is that it often prevents the use of the COLLAPSE clause and thus reduces the available parallelism, as every parallel loop in the whole region needs to have the same bounds, which is not always the case in the vertical direction. Nevertheless, for ICON, larger parallel regions generally yield better GPU performance. When dependencies exist between the different loop nests inside a parallel region, the GANG(STATIC: 1) clause is required. This clause ensures that the same GANG indices will be executed consecutively in each sub-loop, which is otherwise not guaranteed. Since the GANG(STATIC: 1) clause does not degrade performance noticeably, the clause is always added when multiple loop nests are in a larger parallel region. This practice ensures robustness against future modifications by domain scientists who may introduce inter-loop dependencies. This is the second most widely used approach in the code.

An alternative to COLLAPSE is the use of the TILE directive. TILE splits the iteration space into blocks of user-defined size. This can improve cache-usage, especially in cases for neighbor accesses or for memory transposes. For instance, the execution time for this parallel region can be reduced from 19 to 2.5 ms by using the TILE directive instead of COLLAPSE(3), see Listing 3. The choice of tile sizes is hardware-specific and has been selected to yield optimal performance on NVIDIA GPUs, which is generally consistent across most NVIDIA architecture generations. In this case, it has also been demonstrated that even a suboptimal tile size can outperform a plain loop collapse. This approach is used only in cases involving either neighbor accesses or special transposes, which occur in the dynamical core and the radiation scheme, respectively.

Furthermore, advanced optimizations which are specific to different parts of the code are described in Sect. 6.2.

3.4 Dynamics

The Dynamics, or dynamical core of the model, solves the equations governing atmospheric flow. Most components of the dynamical core are shared between the climate and NWP configurations, so only a few additional components had to be ported in addition to the initial work described in Giorgetta et al. (2022). Most loops are parallelized along the nproma and nlev directions when there is no vertical dependency. The code has been GPU-optimized while preserving portability. Although OpenACC directives support execution on both CPU and GPU targets, around ten instances in the code use architecture-specific variants to achieve optimal performance on each platform. These conditional branches enable tailored implementations where the GPU and CPU exhibit substantially different performance characteristics.

3.5 Tracer Transport

The transport module is responsible for the large-scale redistribution of water substances, chemical constituents, or aerosols, for example pollen, by solving the tracer mass continuity equation. The Tracer advection is divided into independent horizontal and vertical advection using the Strang splitting approach see (Reinert, 2020). Both horizontal and vertical transport use semi-Lagrangian algorithms as described in (Reinert and Zängl, 2021). The computational structure of the transport routines resembles that of the dynamical core, involving access patterns from the current edge/cell to neighboring edges or cells. This similarity allows for the adoption of a comparable GPU porting strategy. Different transport algorithms with different computational cost/accuracy trade-offs can be chosen for different tracers. For example, cloud ice, cloud water, precipitation, graupel are transported using the same scheme, while water vapor is treated with a higher-order horizontal advection method. This high-order scheme poses the greatest challenge for GPU porting using OpenACC, as it involves indirect addressing using index lists. To address this, a tailored GPU implementation was developed to ensure efficient execution on GPUs.

3.6 Physics

The so-called physical parameterizations are additional components that describe physical processes not represented by the equations of the dynamics, such as sub-grid scale turbulence, radiation or the physical processes associated to cloud formation and precipitation. These parameterizations are computed on the three-dimensional model grid and are invoked frequently, some at every time step, thus requiring GPU porting. Due to anisotropy in the atmosphere and the timescales of the physical processes relative to atmospheric flow, horizontal interactions can be neglected for most parameterizations. As a result, they can be formulated as column-independent computations. This makes them very attractive for parallelization, as the parameterizations can be trivially parallelized along the horizontal direction, nproma in our case. Many parameterizations, however, do have vertical dependencies, e.g., when the vertical loop must be computed sequentially. This is true, for example, in the main computations of the microphysics and the turbulence. All parameterizations required for the main NWP applications have been ported to GPU.

3.6.1 Treatment of the soil tiles

In ICON, subgrid heterogeneity of the land surface is represented using a so-called tile approach. For example, a given grid point may consist of 50 % forest and 50 % grass, and the tile composition may change dynamically over the simulation. The ICON implementation is such that at each time step a list is created for each type of tile, which are then computed one after the other. Executing each tile type sequentially on the GPU would lead to poor performance, since some tile types may contain too few grid points on a given subdomain to fully utilize the GPU. To circumvent this issue, each tile type is run in an independent queue, equivalent to a CUDA stream on NVIDIA GPUs, using the ASYNC(stream) construct. In combination with CUDA Graphs, an optimization further described in Sect. 6.2.5, this approach yields good performance for parameterization using tiles.

3.6.2 Radiation

The radiation scheme ecRad (Hogan and Bozzo, 2016), developed at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), is operationally used in ECMWF's Integrated Forecasting System (IFS) and is also employed in ICON. The code structure and data layout of ecRad differ significantly from those in the rest of ICON. In addition, its memory consumption is substantial, as it processes approximately 300 wavelengths per grid point. To reduce computational time and modestly decrease memory usage, radiation calculations are performed on a coarser grid, so called reduced grid, approximately four times less dense than the full-resolution grid.

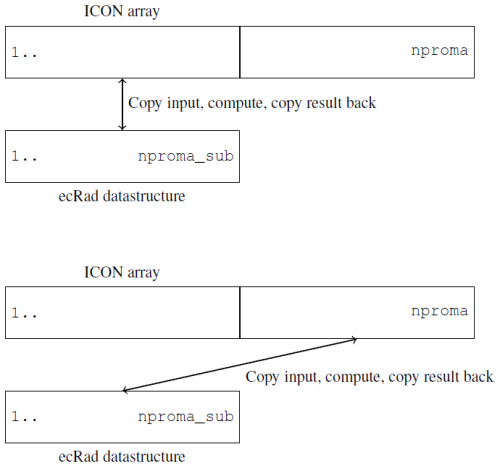

Thus, a solution is still needed to manage memory consumption, and the porting strategy had to be adapted to accommodate the distinct data layout and code structure. To address the memory consumption, we introduced sub-blocking at the interface between ecRad and ICON. The sub-blocking divides the grid points on the reduced grid into nproma_sub-sized batches, which are computed sequentially. This approach ensures that only one radiation sub-block must be held in memory at any given time (see Fig. 2). While this method effectively controls memory usage, it reduces the available parallelism in ecRad. In practice, this trade-off between memory usage and parallelism must be carefully balanced to ensure the computation fits within the available GPU memory while still achieving high hardware utilization.

Figure 2Example of the mapping of an ICON array, of horizontal size nproma, to an ecRad array, of horizontal size nproma_sub, over two iterations of the radiation sub-block loop. This simplified sketch omits additional vertical levels, the wavelength dimension, and the many variables involved in the computation.

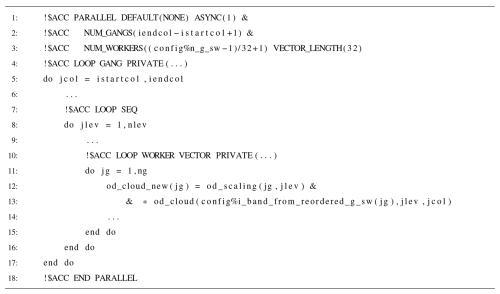

The data layout in ecRad differs from the rest of ICON (see Sect. 3.2) in terms of loop ordering and dimension structure. While ICON typically operates on a two-dimensional domain, ecRad uses a three-dimensional domain: the horizontal dimension matches the standard ICON grid but is further subdivided into nblcks_sub subblocks of size nproma_sub; the vertical dimension retains nlev levels, as in ICON; and a third dimension spans the wavelengths (ng). The resulting index order is (ng, nlev, nproma_sub), instead of ICON’s (nproma, nlev).

This layout introduces challenges for parallelization. The wavelength dimension provides only limited parallelism – on the order of hundreds of wavelengths – insufficient to fully saturate the GPU with GANG VECTOR parallelism. The horizontal dimension can be tuned to provide adequate parallelism, but doing so leads to non-coalesced memory accesses.

To evaluate alternatives, two strategies were tested in standalone versions of ecRad solvers. The first reorders the loops so that the horizontal dimension is innermost, enabling efficient GANG VECTOR parallelism. The second strategy retains the original layout and applies vector parallelism to the wavelength dimension and gang parallelism to the horizontal dimension.

Both strategies performed equally well in our benchmarks. Therefore, we selected the second approach, as illustrated in Listing 4, as it requires fewer code modifications.

Listing 4Example of an OpenACC block from the radiation component, with parallelization along nproma, jc loop, and ng, jg loop.

Note that the jg loop uses WORKER VECTOR parallelism instead of a standard VECTOR loop. This configuration addresses compiler limitations and ensures proper utilization of the desired number of CUDA threads.

3.7 Pollen

Pollen forecasts play a critical role in public health by enabling individuals with allergic conditions – such as hay fever and asthma – to anticipate high-exposure days, plan outdoor activities, and initiate preventive measures like early medication use. The modeling of pollen species in ICON is coupled with the aerosol module ART (Aerosol and Reactive Trace gases (Rieger et al., 2015; Schröter et al., 2018) developed at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT). In general, ART enables modeling a variety of trace gases and aerosols and their associated chemical processes. However, in the context of NWP production at MeteoSwiss, ART is used exclusively to simulate emissions, transport (see Sect. 3.5), sedimentation, and washout processes of five pollen species during their blooming season, namely hazel, alder, birch, grasses, and ambrosia.

For production purposes, only the necessary ART subroutines required for modeling the above-mentioned pollen species are ported to GPUs. These porting efforts follow the same strategy as used for the ICON model (see Sect. 3.2).

3.8 Data Assimilation

Data assimilation combines observational data with model output to generate the best possible estimate of the atmospheric state. This estimate, known as the “analysis”, serves as the initial condition for subsequent numerical weather prediction (NWP) forecasts. Accurate and timely analyses are essential for high-quality short-range forecasts, particularly in data-rich regions like Europe.

Here we consider the so-called KENDA (Kilometer-scale Ensemble Data Assimilation) system (Schraff et al., 2016) used within ICON. It employs an ensemble Kalman filter, specifically the Local Ensemble Transform Kalman Filter (LETKF) by Hunt et al. (2007), to assimilate a wide range of observational data. This includes conventional data from radiosondes, aircraft, wind radars and wind Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) instruments, and surface stations. Additionally, radar-derived surface precipitation rates are assimilated through a technique known as latent heat nudging.

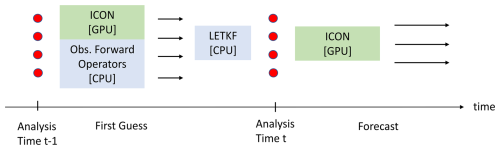

The assimilation cycle consists of several stages, which can be seen in Fig. 3. First, a one-hour ICON ensemble forecast is run starting from the previous ensemble analysis members (red dots) at time t−1, providing the so-called first guess (black arrow). During this forecast, observation operators are applied to transform model variables (e.g., temperature, pressure, humidity) into the observational space and written to disk. The resulting innovations (observation-minus-forecast differences) are passed to the LETKF software to generate the new ensemble analysis at time t (red dots). This new analysis then provides the initial condition for the next forecast cycle. Observation operators pose unique challenges for GPU acceleration. In contrast to the structured grid-based computations found in most of ICON, these operators work in the observational space, which is often sparse and irregular. This makes them poorly suited for execution on GPUs, which require enough data parallelism and benefit from regular memory access patterns for optimal performance. A detailed analysis of the computational patterns and data flow shows that for most operational configurations these operators are only called at very low frequency, every 30 min, and only need a subset of the model state. Based on this, the following hybrid strategy is adopted: the first guess ICON run is executed on the GPU but the data assimilation observation operators are kept on the CPU, and the required data are transferred from GPU to CPU during the run. The data transfer time for this data assimilation component for this configuration corresponds to 0.09 % of the total runtime. The only exception to this porting strategy is the so-called latent heat nudging of radar precipitation, which needs to be called at higher frequency and is therefore ported to GPU. The LETKF analysis step itself remains on the CPU.

3.9 Diagnostics and output

For operational NWP applications, a wide range of diagnostics must be computed to meet the needs of various clients and users. These include, for example, wind gust statistics, lightning indices, and other derived meteorological products. Many of these diagnostics are evaluated at high temporal frequency, often every model time step, which makes GPU acceleration essential for performance. To minimize data transfer overhead, most high-frequency diagnostics have been ported to the GPU. This ensures that intermediate results remain on the GPU memory during the time-stepping loop, avoiding costly CPU-GPU transfers. At designated output intervals, the required diagnostic and model data are transferred from the GPU to the CPU. Output-related operations such as file I/O are then performed on the CPU, which is more suitable for these latency-tolerant and system-dependent tasks. Pre-processing steps for output – such as interpolations to pressure levels, standard height levels, or user-defined layers – are also ported to the GPU and executed before the data transfer. This further reduces CPU workload and ensures that only the final, ready-to-write fields are transferred from GPU memory.

4.1 Probabilistic testing

To ensure the correctness of the GPU port of ICON, a probabilistic testing framework, probtest (Probtest, 2023), was developed. This framework is designed to validate scientific consistency between the GPU and CPU versions of the code while accounting for expected differences due to rounding errors and non-bit-reproducible floating-point behavior. Such differences commonly arise from hardware- and compiler-specific implementations of intrinsic mathematical functions or from numerical optimizations such as fused multiply-add (FMA) operations, which are applied aggressively on GPUs.

The key idea of probtest is to approximate the effect of rounding errors by constructing a CPU-based ensemble in which small perturbations are introduced into selected input fields – typically in the least significant digits. This generates a reference ensemble that captures the natural variability due to rounding effects in the CPU computation.

A short and computationally inexpensive configuration, obtained by using a reduced horizontal domain, is used to run the perturbed ensemble and determine the expected spread of each variable. Based on this ensemble spread, variable-specific statistical tolerances are derived. The GPU simulation is then compared against this CPU-based ensemble using the same configuration, and the test passes if the GPU result falls within the ensemble spread for all diagnosed fields.

This probabilistic test is integrated into the automatic continuous integration (CI) pipeline, and is set up for the set of configurations which are supported on GPU using a reduced domain size. For example one test is using the exact same configuration as the ICON-CH1-EPS configuration, but on a much smaller domain, ensuring that code path used in operation are tested. Every change to the model must pass this validation step to be accepted. In case of physical changes to the model that affect results beyond numerical noise, a new ensemble reference is generated to update the tolerance baseline.

4.2 Validation against observation

Due to the complexity of the model and to the fact that many conditional statements are data-driven, for example a cloud-no-cloud situation, it is not possible to have full code coverage with the above-mentioned automatic testing. In order to ensure the quality of the weather forecast, for every new version of a model that shall be used for production by a weather prediction center, an extensive validation, or so called verification, is required. To this end, the new version of the model is compared against observation for an extended period of time using different metrics such as Mean Error or Root Mean Square Error. Typically, the period of time can be a few weeks for the four seasons for past periods. Such verification has been carried out over multiple seasons for the MeteoSwiss configurations and is described in more details in Sect. 5.2. Such a verification should be repeated in case the model would be used for weather prediction using a different configuration.

4.3 Challenges of porting large community code

Ensuring the correctness of a GPU port for a large community is a critical step in integrating the port into the main code base. However, there is also a human aspect that should not be underestimated when integrating a major code extension that spans a broad range of components in a community-driven code like ICON.

Many ICON components, such as those described in Sect. 3.4 to 3.8, are developed and maintained by individual domain scientists (DSs), who are responsible for the scientific integrity and evolution of their respective modules. In contrast, a research software engineer (RSE) ports a model to GPU by working across multiple code components without affecting the scientific value of the implemented equations. As a result, establishing trust between DSs and RSEs is essential, enabling DSs to understand the modifications required for the GPU port and maintain their ability to maintain and develop the ported code independently.

To facilitate this collaboration, we employ two strategies. First, ported code components are merged incrementally into the main code base. Second, DSs are trained in the basics of the GPU port, OpenACC, and tools for GPU verification, such as tolerance validation with probtest. In parallel, the RSEs gain familiarity with the scientific context of the code they work on, facilitating the interactions.

Incremental porting of the code ensures that the ported code remains up-to-date with the latest scientific advancements, simplifies testing and debugging, and allows DSs to continue working on their components immediately. Also, keeping the partially ported code in a working state enables early integration of GPU tests and probtest into the general ICON CI testing pipeline. Early GPU testing helps to avoid regression when a DS extends an already ported code component. To give a magnitude of the porting effort and the importance of an incremental approach, the source code is about 2 millions line of code, to which about 15 000 OpenACC statement have been added.

The GPU training provided for DSs and other RSEs working on ICON was well received by the ICON developer community, which comprises many scientists without a formal computer science background. The training was tailored specifically to ICON and the use of OpenACC within it. It was offered in live sessions and is also available for self-study, with many supporting documents, guidelines, and hands-on tutorials published and available to ICON developers.

While no formal evaluation was conducted, feedback from participants indicates that the training was perceived as helpful and played a positive role in promoting the acceptance of the GPU port and OpenACC-based development within the ICON community. Finally thanks to the training most ICON developers are able to contribute further changes and additions to ported code. For more complex implementation support from expert GPU developers is provided.

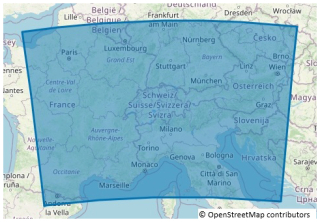

MeteoSwiss currently runs two regional NWP ensemble systems, ICON-CH1-EPS and ICON-CH2-EPS, operationally. The ICON-CH1-EPS configuration has a horizontal grid spacing equivalent to 1 km and 80 vertical levels, with a time step of 10 s. It is run eight times per day, producing 33 h forecasts for 11 members. The 03:00 UTC run is additionally extended to 45 h to fully cover the next day. ICON-CH2-EPS uses a coarser grid spacing of approximately 2.1 km, with the same 80 levels and a 20 s time step. It runs four times per day providing 5 d forecasts for 21 members, offering a broader temporal range while maintaining high spatial resolution for medium-range weather forecasting. In order to capture key weather phenomena for Switzerland, the regional configurations are running on a simulation domain that includes the entire Alpine region as illustrated in Fig. 4 such that ICON-CH1-EPS and ICON-CH2-EPS have, respectively, 1 147 980 and 283 876 horizontal grid points. The initial conditions are provided by the KENDA-CH1 system, which combines a wide range of observations into the model grid and physical equation. KENDA-CH1 has the same computational grid as ICON-CH1-EPS and is run for 41 members. Lateral boundary conditions for these systems are supplied by ECMWF's IFS ENS system, which supplies high-quality global atmospheric data.

5.1 Operational GPU System at CSCS

The MeteoSwiss computing infrastructure is part of the larger Alps Supercomputer at the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre CSCS (Alps, 2025) and is implemented as a so-called versatile cluster, vCluster (Martinasso et al., 2024), deployed across multiple geographical sites for increased operational resilience. The production vCluster named Tasna is hosted in Lausanne (western Switzerland), while the fail-over and R&D vCluster Balfrin is located in Lugano (southern Switzerland). vCluster technology enables flexible configuration of the software environment and allocation of compute resources. Operational forecasting system is composed of 42 nodes, each equipped with one AMD 64-core EPYC CPU and four NVIDIA A100 96 GB GPUs. The nodes are connected by a Cray Slingshot-11 interconnect. Each member of ICON-CH1-EPS is running on 3 nodes, i.e. requiring 33 nodes for the 11 members, while ICON-CH2-EPS is running on 2 nodes per members, e.g. 42 nodes for the 21 members. Finally KENDA-CH1-EPS is running in 2 batches using 2 nodes per member. The 3 configuratoin ICON-CH1-EPS, ICON-CH2-EPS and KENDA-CH1 are run sequentially. The R&D size is of 42 compute nodes or larger depending on the needs and in coordination with CSCS.

5.2 Verification of the MeteoSwiss configuration

After successfully ensuring the consistency of the GPU port against the CPU execution with automated testing (see Sect. 4), an extended verification of the ICON model was conducted. Before introducing it into operations, the forecast quality of the new system was thoroughly assessed and compared to the previous operational system that was based on the COSMO model (Steppeler et al., 2003; Baldauf et al., 2011). To this end, MeteoSwiss ran ICON-CH1-EPS and ICON-CH2-EPS control forecasts on a regular schedule (00:00 and 12:00 UTC runs) starting in summer 2021, transitioning to full ensemble runs in summer 2023. For the first period the model was run on CPU, and from November 2022 on it was run on GPU.

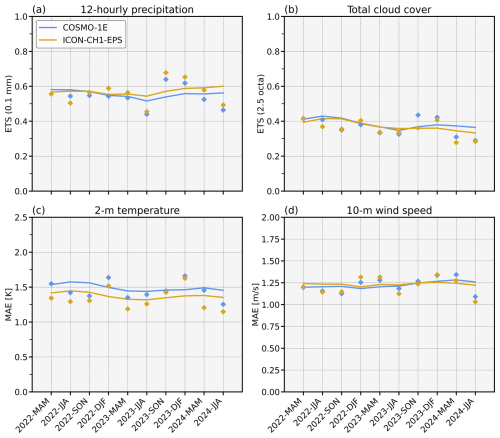

Figure 5 presents an extended verification of ICON-CH1-EPS against the then-operational COSMO-1E system. Since summer 2023, when ICON ensemble data became available, the median of ICON-CH1-EPS consistently outperforms COSMO-1E in terms of the equitable threat score (ETS) for 12-hourly precipitation exceeding 0.1 mm, indicating greater skill in capturing the occurrence of precipitation. Moreover, the mean absolute error (MAE) for 2 m temperature and 10 m wind speed is slightly lower since summer 2023, suggesting an improved overall forecast accuracy for these surface parameters. The only exception is total cloud cover, where the ETS for the 2.5 octa threshold shows slightly lower performance for ICON-CH1-EPS in recent seasons.

Given the slightly improved performance of ICON-CH1-EPS (and ICON-CH2-EPS; not shown) in many of the important parameters (see some of them in Fig. 5), the quality criteria for operational introduction were met and ICON replaced COSMO as the operational NWP system at MeteoSwiss on 28 May 2024. Nevertheless, several known model deficiencies remain, including a warm bias in Alpine valleys, an overestimation of convective precipitation maxima, and an excessive ensemble spread in precipitation forecasts. These deficiencies are the focus of ongoing development with the goal to further enhance the quality of the weather forecasts.

Figure 5Extended verification of COSMO-1E and ICON-CH1-EPS forecasts for the lead-time range of 13–24 h, evaluated against observations from 159 surface stations across Switzerland. Shown are key meteorological verification scores: (a) ETS for 12-hourly precipitation > 0.1 mm, (b) ETS for total cloud cover > 2.5 octa, (c) MAE of 2 m temperature, and (d) MAE of 10 m wind speed. Each panel presents individual seasonal score values (points) and a moving yearly average (lines), computed from the current and the three preceding seasons, for COSMO-1E (blue) and ICON-CH1-EPS (orange). Scores are based on the ensemble median, except for ICON-CH1-EPS prior to JJA 2023, where ensemble data were not yet available. The model was run on GPU from November 2022 on, the results in the previous periods have been obtained on CPU.

6.1 Benchmark configuration

The benchmarking experiments presented in this section are based on the operational ICON-CH1-EPS configuration (see Sect. 5), using a single ensemble member for a one-hour forecast. This choice is representative of a forecast simulation, particularly considering that diagnostic and output components are typically called at hourly intervals, while most other model components are invoked at sub-hourly frequencies. The reported timings includes all data transfers to and from the GPU which are required at initialization, as well as for writting the output. The exact configuration namelist can be found in the open source ICON release (https://www.icon-model.org/, last access: 9 October 2024, release icon-2024.10) under the test name mch_icon-ch1. Each benchmark measurement was repeated ten times, and the mean elapsed time and its standard deviation were recorded. The ICON version used for the benchmarking is based on the release-2024.10, on top of which some of the optimization discussed below have been added. Most of the optimizations are part of the official public release-2025.4 of ICON.

All experiments are run on the Balfrin hybrid system (see the specification in Sect. 5.1). Unless stated otherwise, benchmarks are executed on two GPU nodes, e.g. using a total of 8 NVIDIA A100 96 GB GPUs. The optimization parameter controlling the block size for the horizontal grid nblocks_c is set to 1, and the radiation block parameter nproma_sub is set to 6054. The code was compiled, both for CPU and GPU, using the NVIDIA HPC SDK, nvhpc, compiler version 23.3 with CUDA version 11.8.0.

We note that for a typical NWP run, most of the run time is spent in the dynamics, about 50 % , and the physics, about 30 %. The rest is spend in the communication, 8 %, initialization, which includes the data transfers to the GPU, 4 %, diagnostics and output which are below 5 % each. The output is done asynchronously, and is to a large part overlapped with the computations.

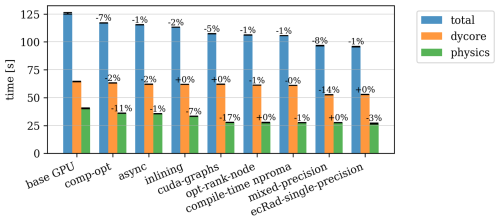

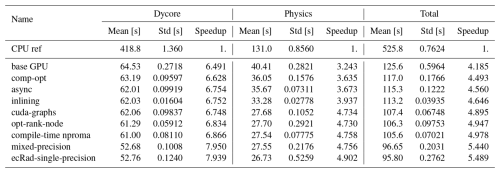

6.2 GPU optimization

After porting and validating the ICON code on GPUs, a range of optimizations have been introduced to improve performance. These optimizations are described below, and the resulting performance of the combined optimization is shown in Table 1 and summarized in Fig. 6.

Table 1Performance metrics for different parts of the model with various optimizations. For the speedup reference the CPU version is used, which includes all the optimizations that also affects the CPU performance like CPU optimization flags, in-lining, opt-rank-node, mixed-precision and ecRad in single precision.

6.2.1 Baseline

The GPU timings are compared to a CPU reference. Since some of the optimizations also improve the CPU runtime, we use the best-performing optimized version as the CPU reference, including mixed precision and radiation in single precision. The CPU reference is compiled with the following optimization flags -O2 -Mrecursive -Mallocatable=03 -Mbackslash -Mstack_arrays inlcuding inlining and is run using 8 AMD 7713 64 cores EPYC Milan CPUs, using MPI parallelization over all cores. The parameters for the horizontal blocking are set to nproma =8 and nproma_sub =8 which are optimal values on CPU for this configuration. The total time for this 1 h-benchmark is 525.8 s. Note that due to an issue with the nvhpc compiler available on the system, the hybrid OpenMP – MPI parallelization did not work on the CPU for this configuration and is not reported in the Rable 1. The problem was reported to Nvidia, and shall be adressed in later release of the compiler. The base GPU code is compiled with -O -Mrecursive -Mallocatable=03 -Mbackslash -acc=verystrict -Minfo=accel,inline -gpu=cc80. Comparing the CPU reference on 8 CPU sockets with the GPU code running on 8 A100 GPUs, we observe a total runtime of 125.6 s and a speed-up factor of about 4.2. Note that we favor this socket-to-socket comparison as opposed to a node-to-node comparison since the GPU nodes have more GPUs than CPUs which would be too favorable for the GPUs. For ecRad, the additional flag -gpu=maxregcount:96 is used to limit the maximum number of registers per thread on the GPU, which improves performance. However, for the entire ICON model, no single register limit provides optimal performance across all kernels. Adjusting the register count on a per-file basis could be considered, but this approach would require considerable effort. Since the weather model ICON is mostly memory bandwidth limited (Adamidis et al., 2025), it is instructive to compare the speedup observed with the hardware specification. The NVIDIA A100 96 GB and the AMD 7713 EPYC CPU have a maximum theoretical bandwidth to the main memory of, respectively, 1560 and 204.8 GB s−1, which gives a ratio of 7.8. This is consistent with the observed speedup of a factor of 4.3, which suggests that the initial port is performing reasonably well and that no significant computations have been left on the CPU. But it also indicates that there is potential room for improvement.

6.2.2 Compiler optimizations level and flags, comp-opt

First, various optimization flags at the compiler level have been investigated and compared. Aggressive optimization flags such as -03 or -fasthmath have not been considered for accuracy and validation reasons. Using -O2 and -Mstack_arrays noticeably reduces the total runtime by about 6.8 % to 117.0 s Most of the gain comes from the flag -Mstack_arrays which places all temporary Fortran automatic arrays on the stack. Although this change only affects memory allocation on the CPU, it also impacts GPU runtime when using OpenACC, because these automatic arrays are still allocated, even if never used on the CPU. The effect is, in fact, larger for the GPU run, because of the very large nproma used (see Sect. 3.2), which leads to large temporary arrays.

6.2.3 Asynchronous execution between CPU and GPU

By default, OpenACC synchronizes CPU and GPU execution, such that the CPU needs to wait for the GPU kernels to complete before being able to proceed. This can be adapted by using the OpenACC ASYNC(INT) constructs in parallel regions, allowing the CPU to continue execution after launching the kernel. Asynchronous computation needs a careful analysis of the code to ensure that no data computed on the GPU are used at a later stage on the CPU, while computation is still ongoing on the GPU. In such a case, the construct ACC WAIT(INT_LIST) is used to wait for completion of the GPU execution before proceeding. The OpenACC ASYNC construct further allows the specification of the queue – corresponding to the cuda-stream on NVIDIA devices – where the asynchronous execution is done. In most of the ICON code, the asynchronous queue is explicitly set to 1, except for specific parts where multiple code paths are executed in parallel queues. This is, for example, the case for the different tiles of the soil as described in Sect. 6.2.5. With asynchronous execution, the CPU can proceed and launch multiple kernels, significantly reducing or even eliminating kernel launch overhead. As shown in Table 1 this brings down the total runtime to 115.3 s, i.e., about 1.5 % additional performance improvement.

6.2.4 Inlining

Inlining is a general optimization technique that replaces the call to a function by the actual code of the function. This can reduce function call overhead and allows for additional compile-time optimizations. It is particularly beneficial for functions which are called from the innermost-loop. In Fortran there is no language construct, as in the C programming language for example, to control inlining. However, most compiler vendors provide solutions to inline functions. With the nvhpc (NVIDIA) compiler there is a pre-compilation step added where the user gives a list of functions that should be inlined, such that these functions are extracted as code into an inline library. This inline library is then used for the compilation of the full code. Inlining is not always beneficial and significantly increases the compilation time. For this reason, inlining is restricted to functions resulting in a significant performance improvement. In ICON, these are primarily in the physics scheme. The total runtime reduces to 113.2 s, which corresponds to a relative improvement of 1.8 %.

6.2.5 CUDA Graphs

CUDA Graphs are an NVIDIA-specific GPU optimization feature that allow GPU workloads to be expressed as a directed acyclic graph (DAG) of operations, rather than launching individual kernels sequentially. This enables the GPU runtime to schedule and execute kernels with significantly reduced launch overhead and memory allocation costs. In ICON, CUDA Graphs are employed within selected physical parameterizations, most notably in the turbulence and soil components of the NWP configuration. In addition to the turbulence transfer and the soil model, the CUDA graph is used in association with multiple asynchronous queues to run all the independent soil type tiles concurrently in different GPU queues.

At runtime, all GPU kernels, memory allocations, and de-allocations with their respective dependencies between the OpenACC extension APIs accx_begin_capture_async and accx_end_capture_async are recorded as a graph. After that, the recorded graph can be executed on the GPU via the accx_graph_launch API multiple times, which is called a graph replay.

Although the required code changes are minimal, their use introduces certain limitations, which may require further adaptations to the code. The most critical aspect is that, during graph replay, no CPU work should be carried out; only prerecorded GPU kernels should be launched. In addition, all OpenACC statements within the capture region must be asynchronous. Moreover, kernel parameters are captured by value during the recording and cannot be changed later in the execution. This means that all array shapes and pointers cannot change from one graph replay to another. In ICON some fields have two time levels, so that the pointers associated with such fields are different for odd and even time steps. Therefore, for the part of the code that uses fields with two time levels, two graphs need to be recorded, one for odd and one for even time steps.

The application of CUDA Graphs to the soil and turbulence routines yields significant local speedups (3× and 3.5×, respectively). While these routines constitute a relatively small portion of the total runtime, the aggregate benefit of CUDA Graphs translates to a 5 % overall runtime reduction, bringing the benchmark execution time down to 107.4 s.

6.2.6 opt-rank-distribution

When running the model on multi-GPU nodes, there is one MPI task associated to each GPU. In addition, some of the remaining CPU cores on the node are used for I/O related tasks, namely asynchronous I/O MPI tasks and a pre-fetch MPI task. Pure CPU MPI tasks should be evenly distributed over all nodes. Since I/O related tasks are at the end of the MPI communicator, they can be distinguished from compute tasks in a straightforward way by using the slurm SBATCH --distribution=cyclic command. However, this has the drawback that close MPI ranks are on different nodes, which could mean close domains are on different nodes, leading to more inter-node communication. An optimization of the rank distribution (opt-rank-distribution) can be achieved using SBATCH --distribution=plane=4. In this plane distribution, tasks are allocated in blocks of size 4 and distributed in a round-robin fashion across the allocated nodes. With this change, the total time improved by 1 % to 106.3 s.

6.2.7 Compile-time nproma

The parameter nproma is usually set during runtime via a namelist switch. The nproma is chosen for the best performance dependent on the computing architecture. In many architectures, this is fixed to accommodate for the cache size or vector length. For GPU, the nproma is chosen to be as large as possible and dependent on the number of grid points. Setting the value at compile time provides a performance increase. Although this optimization is available, it is currently not used for the operation at MeteoSwiss since the two configurations ICON-CH1-EPS and ICON-CH2-EPS have different numbers of points and therefore would require two different executables with different nproma. With this optimization, a gain of 0.7 % is obtained corresponding to a total runtime of 106.3 s.

6.2.8 Dycore mixed-precision

Using single precision can give multiple advantages over double precision. On the one hand, more floating point operations can be done in the same time as double precision operations. On the other hand, it decreases memory pressure, which is useful, especially considering the limited amount of memory available on the GPU. The drawback of using single precision is that the errors of using floating point numbers increase, and the effect on the numerical integration need to be carefully analyzed. For this reason a mixed-precision approach has been implemented in ICON's dycore. Scientific expertise determines which fields and operations can be put in single precision. The mixed-precision model was validated against a double-precision version by comparing to observations over a long period of time, which showed no impact on the meteorological scores. The performance is improved by 8 % to 96.65 s. This performance improvement is somewhat less that one could expect, and may results from several aspects. First there are only a limited number of fields in ICON that are set to single precisions in the dycore. Another possible explanation is that the overhead of other operation such as integer arithmetic for example for index computation, might be taking a non significant part of the time, and become a limitation in mixed precision.

6.2.9 ecRad single-precision

Similar considerations as for the dycore have been made for the radiation parameterization ecRad regarding the floating-point precision. We also note that ecRad is already used in single-precision for operations at the ECMWF in combination with the weather model IFS which provides additional validation to this approach. With this change, the total runtime is improved by 0.9 % to 95.80 s. The ecRad parameterization is a memory-intensive component such that using single-precision has a significant impact on the total memory consumption. This could be beneficial for the overall performance since it allows to increase nproma_sub to use more parallelism and reduce launching overhead. The flag to limit the maximum use register is adapted to -gpu=maxregcount:48.

Looking at the overall improvement, the benchmark runtime was optimized by 23 % from 125.6 to 95.80 s. Comparing to the CPU reference at 536.5 s this gives a final socket-to-socket speedup of 5.5× on the GPU. This speedup factor is consistent with previous results for climate configuration setup (Giorgetta et al., 2022). The speed up factor also means that compared to a CPU only a GPU system for operation is more compact, 5.5× time more CPUs would be needed for the required time to solution. Although we did not perform energy measurement in this work, a previous study (Cumming et al., 2014) considering a similar model, shows that the better performance also translates in a more energy efficient system.

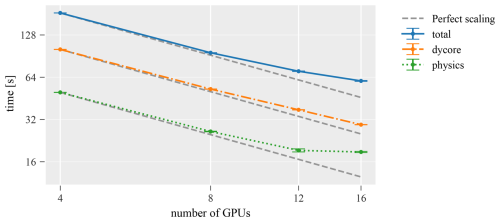

6.3 Strong scaling

To assess strong scaling behavior, the ICON-CH1 benchmark is run using an increasing number of GPUs. The reference time is given for 4 GPUs, which is the smallest number on which the problem fits in terms of memory. The most optimized version from the previous Sect. 6.2, which is the ecRad-single-precision version, is used for this test. In Fig. 7, it can be seen that the problem scales well up to 12 GPUs. Beyond 12 GPUs, there is a noticeable degradation in performance in the physics component, while the dynamical core (dycore) continues to scale well. Considering that the ICON-CH1-EPS grid has 1 147 980 grid points, with 12 GPUs the number of grid points per GPU is below 100 000. At this point, the per-GPU workload becomes too small to fully utilize the compute and memory throughput capabilities of the NVIDIA A100 GPUs. In particular, the ability to overlap memory access with computation is reduced, leading to under-utilization. We also note that there is little communication in the physics as compared to the dycore, which further supports that the non-optimal scaling results from non-optimal use of the GPUs rather than communication overhead.

6.4 Timing for the operational configuration

For the operational ICON-CH1-EPS configuration at MeteoSwiss, each 33 h ensemble forecast must be completed within 50 min (3000 s) to meet the stringent timing requirements for delivering downstream critical products to clients. When ICON was first deployed operationally in May 2024, not all GPU optimizations were yet in place. At that time, the runtime on two nodes (8 NVIDIA A100 GPUs) was approximately 3200 s, exceeding the operational time limit. As a result, each ensemble member had to be executed on three nodes (12 GPUs) to stay within the required timeframe. After applying the full set of optimizations, the runtime for a 33 h forecast on two nodes was reduced to 2642 s, well within the operational constraint, enabling more efficient and cost-effective use of computational resources.

We have successfully ported all essential components of the ICON model required for operational numerical weather prediction (NWP) to GPUs using OpenACC compiler directives. This includes the dynamical core, all physical parameterizations, and the data assimilation system (KENDA). The porting and optimization strategy has enabled a single ensemble member of the operational ICON-CH1-EPS configuration to run within the required time-to-solution on 8 NVIDIA A100 GPUs.

When comparing the same number of CPU and GPU sockets, the speedup on the GPU hardware is 5.5×. This potentially allows for a much more compact and energy-efficient system than a CPU-only system. The OpenACC approach enabled the implementation of changes in a step-by-step manner in the code while maintaining performance on other architectures. Besides the MeteoSwiss configuration, several other configurations are also supported and tested including one global configuration from Germany's National Meteorological Service, the Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD).

All changes have been merged into the main ICON code and OpenACC training in ICON was provided to the community to promote a seamless adoption of the port and would allow other NWP centers or users to run ICON on GPU. The code changes are included in the ICON open-source distribution, with the exception of the data assimilation part, making it available for many use cases to the broader NWP community. The ICON model was thoroughly verified over multiple seasons against observations and the previous operational model COSMO achieving the required quality level for the MeteoSwiss configurations. The port allowed MeteoSwiss to be the first weather service to use the ICON model on the GPU in production for operational NWP prediction. Thanks to the computing efficiency of GPUs, MeteoSwiss can run, in particular, the ICON-CH1-EPS configuration at up to 1 km resolution, which remains one of the highest-resolution ensemble systems to date.

Beyond immediate operational gains, the GPU-capable ICON model is well positioned to benefit from the growing convergence of physics-based and machine learning (ML) approaches in weather and climate modeling. Indeed in case of an hybrid setup both physical model and the ML inference could be run on GPU without requiring data transfer. The main synergy for MeteoSwiss with the described production system is that the GPU infrastructure that was acquired for the NWP forecast can be used for training and inference of ML weather models.

Nonetheless, the OpenACC approach comes with limitations in terms of maintainability, optimization and portability. The directives have been added on top of existing OpenMP but also vendor specific optimization directives which decrease the overall readability of the code. Furthermore, currently the OpenACC standard is only fully supported by the nvhpc compiler on NVIDIA hardware. Running ICON with AMD GPUs is, for example, only possible on a Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) system using the Cray compiler for climate configuration, while there are some unresolved issues with some NWP components on such system. Finally, there are no solutions for running OpenACC code on Intel GPUs. To improve portability and performance on GPU hardware, the ICON community is investigating several other approaches, including a rewrite using the Python domain-specific language GT4Py (Paredes et al., 2023; Dipankar et al., 2025).

The full ICON version needed for all production configurations at MeteoSwiss, including the closed source Data Assimilation components for the KENDA cycle, used in the paper is archived on the Zenodo server (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15674269, ICON partnership, 2024b). This code version is available under restricted access for review and for research purpose. For the icon-ch1-eps benchmark used for the performance results reported in the paper, the data assimilation component is not needed, the benchmark results can be reproduced using the official open-source release source code, configurations and scripts available under BSD-3 License archived on the World Data Center for Climate server from DKRZ (https://doi.org/10.35089/WDCC/IconRelease2024.10, ICON partnership, 2024a). A copy of the input data required to run the ICON-CH1-EPS benchmark as well as the raw data used for the verification for the years 2021–2024 is available on the Zenodo server under https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16760638 (Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss, 2024).

XL supervised and coordinated the GPU porting effort and ported part of the code to OpenACC. DH ported several components to OpenACC in particular the radiation scheme and optimized the code. FG ported components of the model in particular the data assimilation to the GPU and worked on optimizations. AL worked on the testing infrastructure and ported components to OpenACC. AW was the project manager for the operationalization of ICON at MeteoSwiss and coordinated the effort between the GPU port and operational requirements. CM worked on the optimization of the dycore. DA worked on many optimizations in particular in the dycore and implemented the CUDA Graph solution. JJ ported part of the code, in particular some diagnostics to the GPU. MaJ ported several components in particular those required for the DWD operational NWP setup. MiJ ported components required for regional climate modeling setups. MS ported the pollen module and worked on the optimizations. RD ported components, in particular the microphysics and turbulence parameterizations and developed the probtest infrastructure. US optimized the convection scheme. VS ported the subgrid scale orography parameterization. WS ported many components, in particular the dycore and infrastructure such as the communication. ClM and DL contributed to the Data Assimilation system. PB prepared the system for operation. CO supervised part of the work. MA supervised the improvement of the model configuration at MeteoSwiss. LJ and DL optimized and improved the model configuration. PK and AP worked on the verification of the model. OF and PS supervised part of the work and operationalization of the system. MK and MI worked on the computing system to make it ready for operation. RA and TS supervised the preparation and project of the operational computing infrastructure. BC prepared the operational software stack. SK supported the implementation of the build system. RM supported the implementation of the CI testing infrastructure for the operational system.

Author Dmitry Alexeev is employed by NVIDIA. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors would like to thank the ICON partners MPI-M, DWD, DKRZ, and C2SM, as well as the ICON developers, for their support and, in particular, for their help with reintegration into the main code, resolving merge conflicts, and addressing various issues. Special thanks go to the German computing center, DKRZ, for providing the Buildbot CI testing infrastructure, which was key to the success of this project. The authors would also like to thank the CSCS engineers for their excellent support and for ensuring the system's success and stability. The GPU port of ICON for NWP application was coordinated as part of the priority project IMPACT of the COSMO consortium. The authors acknowledge the use of the AI tool DeepL Write for improving the style of some sentences in the manuscript. This paper is dedicated to our beloved colleague, André Walser, who passed away in February 2025. He played a leading role in bringing the ICON model into production at MeteoSwiss.

This research has been supported by the C2SM, MeteoSwiss-ETHZ funding Weiterentwicklungen-ICON (WEW-ICON).

This paper was edited by Lars Hoffmann and reviewed by Balthasar Reuter and one anonymous referee.

Adamidis, P., Pfister, E., Bockelmann, H., Zobel, D., Beismann, J.-O., and Jacob, M.: The real challenges for climate and weather modelling on its way to sustained exascale performance: a case study using ICON (v2.6.6), Geosci. Model Dev., 18, 905–919, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-18-905-2025, 2025. a, b

Adams, S., Ford, R., Hambley, M., Hobson, J., Kavčič, I., Maynard, C., Melvin, T., Müller, E., Mullerworth, S., Porter, A., Rezny, M., Shipway, B., and Wong, R.: LFRic: Meeting the challenges of scalability and performance portability in Weather and Climate models, Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing, 132, 383–396, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpdc.2019.02.007, 2019. a

Alps: Alps CSCS, https://www.cscs.ch/computers/alps (last access: 1 October 2025), 2025. a

Baldauf, M., Seifert, A., Förstner, J., Majewski, D., Raschendorfer, M., and Reinhardt, T.: Operational convective-scale numerical weather prediction with the COSMO model: Description and sensitivities, Mon. Weather Rev., 139, 3887–3905, https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-10-05013.1, 2011. a

Bauer, P., Thorpe, A., and Brunet, G.: The quiet revolution of numerical weather prediction, Nature, 525, 47–55, 2015. a

Cumming, B., Fourestey, G., Fuhrer, O., Gysi, T., Fatica, M., and Schulthess, T. C.: Application Centric Energy-Efficiency Study of Distributed Multi-Core and Hybrid CPU-GPU Systems, in: SC '14: Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, 819–829, https://doi.org/10.1109/SC.2014.72, 2014. a

Dahm, J., Davis, E., Deconinck, F., Elbert, O., George, R., McGibbon, J., Wicky, T., Wu, E., Kung, C., Ben-Nun, T., Harris, L., Groner, L., and Fuhrer, O.: Pace v0.2: a Python-based performance-portable atmospheric model, Geosci. Model Dev., 16, 2719–2736, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-16-2719-2023, 2023. a

Dipankar, A., Bianco, M., Bukenberger, M., Ehrengruber, T., Farabullini, N., Gopal, A., Hupp, D., Jocksch, A., Kellerhals, S., Kroll, C. A., Lapillonne, X., Leclair, M., Luz, M., Müller, C., Ong, C. R., Osuna, C., Pothapakula, P., Röthlin, M., Sawyer, W., Serafini, G., Vogt, H., Weber, B., and Schulthess, T.: Toward Exascale Climate Modelling: A Python DSL Approach to ICON’s (Icosahedral Non-hydrostatic) Dynamical Core (icon-exclaim v0.2.0), EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2025-4808, 2025. a, b

Donahue, A. S., Caldwell, P. M., Bertagna, L., Beydoun, H., Bogenschutz, P. A., Bradley, A. M., Clevenger, T. C., Foucar, J., Golaz, C., Guba, O., Hannah, W., Hillman, B. R., Johnson, J. N., Keen, N., Lin, W., Singh, B., Sreepathi, S., Taylor, M. A., Tian, J., Terai, C. R., Ullrich, P. A., Yuan, X., and Zhang, Y.: To Exascale and Beyond – The Simple Cloud-Resolving E3SM Atmosphere Model (SCREAM), a Performance Portable Global Atmosphere Model for Cloud-Resolving Scales, Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, 16, e2024MS004314, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024MS004314, 2024. a

Escobar, J., Wautelet, P., Pianezze, J., Pantillon, F., Dauhut, T., Barthe, C., and Chaboureau, J.-P.: Porting the Meso-NH atmospheric model on different GPU architectures for the next generation of supercomputers (version MESONH-v55-OpenACC), Geosci. Model Dev., 18, 2679–2700, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-18-2679-2025, 2025. a

Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss: ICON-CH1-EPS input and verification data, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16760638, 2024. a

Fuhrer, O., Osuna, C., Lapillonne, X., Gysi, T., Cumming, B., Bianco, M., Arteaga, A., and Schulthess, T. C.: Towards a performance portable, architecture agnostic implementation strategy for weather and climate models, Supercomputing Frontiers and Innovations, 1, 45–62, 2014. a

Giorgetta, M. A., Sawyer, W., Lapillonne, X., Adamidis, P., Alexeev, D., Clément, V., Dietlicher, R., Engels, J. F., Esch, M., Franke, H., Frauen, C., Hannah, W. M., Hillman, B. R., Kornblueh, L., Marti, P., Norman, M. R., Pincus, R., Rast, S., Reinert, D., Schnur, R., Schulzweida, U., and Stevens, B.: The ICON-A model for direct QBO simulations on GPUs (version icon-cscs:baf28a514), Geosci. Model Dev., 15, 6985–7016, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-15-6985-2022, 2022. a, b, c, d

Hogan, R. J. and Bozzo, A.: ECRAD: A new radiation scheme for the IFS, vol. 787, European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reading, UK, https://www.ecmwf.int/sites/default/files/elibrary/2016/16901-ecrad-new-radiation-scheme-ifs.pdf (last access: 15 November 2016), 2016. a

Hunt, B. R., Kostelich, E. J., and Szunyogh, I.: Efficient data assimilation for spatiotemporal chaos: A local ensemble transform Kalman filter, Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 230, 112–126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physd.2006.11.008, 2007. a

ICON partnership: ICON model, 2024.10, World Data Center for Climate [code], https://doi.org/10.35089/WDCC/IconRelease2024.10, 2024a. a

ICON partnership: ICON model with Data Assimilation, 2024.10_withDA, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15674269, 2024b. a

Lapillonne, X. and Fuhrer, O.: Using compiler directives to port large scientific applications to GPUs: An example from atmospheric science, Parallel Processing Letters, 24, 1450003, https://doi.org/10.1142/S0129626414500030, 2014. a

Martinasso, M., Klein, M., Cumming, B., Gila, M., Cruz, F., Madonna, A., Ballesteros, M. S., Alam, S. R., and Schulthess, T. C.: Versatile Software-Defined Cluster for HPC Using Cloud Abstractions, Computing in Science & Engineering, 26, 20–29, https://doi.org/10.1109/MCSE.2024.3394164, 2024. a

Nickolls, J., Buck, I., Garland, M., and Skadron, K.: Scalable parallel programming with cuda: Is cuda the parallel programming model that application developers have been waiting for?, Queue, 6, 40–53, 2008. a

Palmer, T.: Climate forecasting: Build high-resolution global climate models, Nature, 515, 338–339, 2014. a

Paredes, E. G., Groner, L., Ubbiali, S., Vogt, H., Madonna, A., Mariotti, K., Cruz, F., Benedicic, L., Bianco, M., VandeVondele, J., and Schulthess, T. C.: GT4Py: High Performance Stencils for Weather and Climate Applications using Python, arXiv [preprint], https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2311.08322, 2023. a

Probtest: Probability testing, GitHub [code], https://github.com/MeteoSwiss/probtest (last access: 29 September 2024), 2023. a

Reinert, D.: The Tracer Transport Module Part I: A Mass Consistent Finite Volume Approach with Fractional Steps, Tech. rep., Deutscher Wetterdienst, https://doi.org/10.5676/DWD_pub/nwv/icon_005, 2020. a

Reinert, D. and Zängl, G.: The Tracer Transport Module Part II: Description and Validation of the Vertical Transport Operator, Tech. rep., Deutscher Wetterdienst, https://doi.org/10.5676/DWD_pub/nwv/icon_007, 2021. a

Rieger, D., Bangert, M., Bischoff-Gauss, I., Förstner, J., Lundgren, K., Reinert, D., Schröter, J., Vogel, H., Zängl, G., Ruhnke, R., and Vogel, B.: ICON–ART 1.0 – a new online-coupled model system from the global to regional scale, Geosci. Model Dev., 8, 1659–1676, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-8-1659-2015, 2015. a

Schraff, C., Reich, H., Rhodin, A., Schomburg, A., Stephan, K., Periáñez, A., and Potthast, R.: Kilometre-scale ensemble data assimilation for the COSMO model (KENDA), Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 142, 1453–1472, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.2748, 2016. a

Schröter, J., Rieger, D., Stassen, C., Vogel, H., Weimer, M., Werchner, S., Förstner, J., Prill, F., Reinert, D., Zängl, G., Giorgetta, M., Ruhnke, R., Vogel, B., and Braesicke, P.: ICON-ART 2.1: a flexible tracer framework and its application for composition studies in numerical weather forecasting and climate simulations, Geosci. Model Dev., 11, 4043–4068, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-4043-2018, 2018. a

Shimokawabe, T., Aoki, T., Ishida, J., Kawano, K., and Muroi, C.: 145 TFlops Performance on 3990 GPUs of TSUBAME 2.0 Supercomputer for an Operational Weather Prediction, Procedia Computer Science, 4, 1535–1544, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2011.04.166, 2011. a

Steppeler, J., Doms, G., Schättler, U., Bitzer, H. W., Gassmann, A., Damrath, U., and Gregoric, G.: Meso-gamma scale forecasts using the nonhydrostatic model LM, Meteorol. Atmos. Phys., 82, 75–96, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00703-001-0592-9, 2003. a

Ubbiali, S., Kühnlein, C., Schär, C., Schlemmer, L., Schulthess, T. C., Staneker, M., and Wernli, H.: Exploring a high-level programming model for the NWP domain using ECMWF microphysics schemes, Geosci. Model Dev., 18, 529–546, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-18-529-2025, 2025. a

Zängl, G., Reinert, D., Rípodas, P., and Baldauf, M.: The ICON (ICOsahedral Non-hydrostatic) modelling framework of DWD and MPI-M: Description of the non-hydrostatic dynamical core, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 141, 563–579, 2015. a, b

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The ICON model

- GPU port for NWP

- Validation and acceptance

- Operational NWP configuration at MeteoSwiss

- Optimization and performance results

- Conclusions

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The ICON model

- GPU port for NWP

- Validation and acceptance

- Operational NWP configuration at MeteoSwiss

- Optimization and performance results

- Conclusions

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References