the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The ISIMIP groundwater sector: a framework for ensemble modeling of global change impacts on groundwater

Tanjila Akhter

Annemarie Bäthge

Ricarda Dietrich

Sebastian Gnann

Simon N. Gosling

Danielle Grogan

Andreas Hartmann

Stefan Kollet

Rohini Kumar

Richard Lammers

Yan Liu

Nils Moosdorf

Sara Nazari

Chibuike Orazulike

Yadu Pokhrel

Jacob Schewe

Mikhail Smilovic

Maryna Strokal

Wim Thiery

Yoshihide Wada

Shan Zuidema

Inge de Graaf

Groundwater serves as a crucial freshwater resource for people and ecosystems, playing a vital role in adapting to climate change. Yet, its availability and dynamics are affected by climate variations, changes in land use, and abstraction. Despite its importance, our understanding of how global change will influence groundwater in the future remains limited. Multi-model ensembles are powerful tools for impact assessments; compared to single-model studies, they provide a more comprehensive understanding of uncertainties and enhance the robustness of projections by capturing a range of possible outcomes. However, to date, no ensemble of groundwater models has been available to assess the impacts of global change. Here, we present the new Groundwater sector within ISIMIP, which combines multiple global, continental, and regional-scale groundwater models. We describe the rationale for the sector, the sectoral output variables that underpinned the modeling protocol, and showcase current model differences and possible future analysis. Currently, eight models are participating in this sector, ranging from gradient-based groundwater models to specialized karst recharge models, each producing up to 19 out of 23 modeling protocol-defined output variables. To showcase the benefits of a joint sector, we utilize available model outputs of the participating models to show the substantial differences in estimating water table depth (global arithmetic mean 6–127 m) and groundwater recharge (global arithmetic mean 78–228 mm yr−1), which is consistent with recent studies on the uncertainty of groundwater models, but with distinct spatial patterns. We further outline synergies with 13 of the 17 existing ISIMIP sectors and specifically discuss those with the global water and water quality sectors. Finally, this paper outlines a vision for ensemble-based groundwater studies that can contribute to a better understanding of the impacts of climate change, land use change, environmental change, and socio-economic change on the world's largest accessible freshwater store – groundwater.

- Article

(4356 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Groundwater is the world's largest accessible freshwater resource, vital for human and environmental well-being (Huggins et al., 2023; Scanlon et al., 2023), serving as a critical buffer against water scarcity and surface water pollution (Foster and Chilton, 2003; Schwartz and Ibaraki, 2011). It supports irrigated agriculture, which supports 17 % of global cropland and 40 % of food production (Döll and Siebert, 2002; Perez et al., 2024; United Nations, 2022; Rodella et al., 2023). However, unsustainable extraction in many regions has led to declining groundwater levels, the drying of rivers, lakes and wells, land subsidence, seawater intrusion, and aquifer depletion (e.g., Bierkens and Wada, 2019; de Graaf et al., 2019; Rodell et al., 2009).

The pressure on groundwater systems intensifies due to the combined effects of population growth, socioeconomic development, agricultural intensification (Niazi et al., 2024; Wada et al., 2012), and climate change (Taylor et al., 2013; Gleeson et al., 2020; Cuthbert et al., 2023; Huggins et al., 2023), e.g., through a change in groundwater recharge (Portmann et al., 2013; Hartmann et al., 2017; Reinecke et al., 2021; Berghuijs et al., 2024; Kumar et al., 2025). Rising temperatures and altered precipitation patterns are already reshaping water availability and demand, with significant implications for groundwater use. For instance, changing aridity is expected to influence groundwater recharge rates (Berghuijs et al., 2024), yet the consequences for groundwater level dynamics remain unclear (Moeck et al., 2024; Cuthbert et al., 2019), and how possible changes will affect groundwater's role in sustaining ecosystems, agriculture, and human water supplies.

Understanding the impacts of climate change and the globalized socio-economy on groundwater systems (Rodella et al., 2023; Gisser and Sánchez, 1980) requires a large-scale perspective that extends from continental to global scales (Haqiqi et al., 2023; Konar et al., 2013; Dalin et al., 2017; Gleeson et al., 2021). While groundwater management is traditionally conducted at local or regional scales (Gleeson and Paszkowski, 2014), aquifers often span administrative boundaries, and overextraction in one area can have far-reaching effects not captured by a local model. Moreover, groundwater plays a critical role in the global hydrological cycle, influencing surface energy distribution, soil moisture, and evapotranspiration through processes such as capillary rise (Condon and Maxwell, 2019; Maxwell et al., 2016) and supplying surface waters with baseflow (Winter, 2007; Xie et al., 2024). These interactions underscore the importance of groundwater in buffering climate dynamics over extended temporal and spatial scales (Keune et al., 2018) and underscore the need for a global perspective of the water-climate cycle. While large-scale climate-groundwater interactions are starting to become understood (Cuthbert et al., 2019), current global water and climate models may not always capture these feedbacks as most either do not consider groundwater at all or only include a simplified storage bucket, limiting our understanding of how climate change will affect the water cycle as a whole (Gleeson et al., 2021; Condon et al., 2021).

The inclusion of groundwater dynamics in global hydrological models remains a considerable challenge due to data limitations and computational demands (Gleeson et al., 2021). Simplified representations, e.g., linear reservoir (Telteu et al., 2021), often fail to capture the complexity of groundwater-surface water interactions, lateral flows at local or regional scales, or the feedback between groundwater pumping and streamflow (de Graaf et al., 2017; Reinecke et al., 2019). These processes are crucial for evaluating water availability, particularly in regions heavily dependent on groundwater. For instance, lateral flows sustain downstream river baseflows and groundwater availability, which, in turn, impact water quality and ecological health (Schaller and Fan, 2009; Liu et al., 2020). Not including head dynamics may lead to overestimation of groundwater depletion (Bierkens and Wada, 2019). Multiple continental to global-scale groundwater models have been developed in recent years to represent these critical processes (for an overview, see also Condon et al., 2021, and Gleeson et al., 2021).

While current model ensembles of global water assessments have not yet incorporated gradient-based groundwater processes, they have already significantly advanced our understanding of the large-scale groundwater system. The Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP), analogous to the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) for climate models (Eyring et al., 2016a), is a well-established community project to carry out model ensemble experiments for climate impact assessments (Frieler et al., 2017, 2024). The current generation of models in the Global Water Sector of ISIMIP often represents groundwater as a simplified storage that receives recharge, releases baseflow, and can be pumped (Telteu et al., 2021). Still, it lacks lateral connectivity and head-based surface-groundwater fluxes. Nevertheless, the ISIMIP water sector provided important insights on, for example, future changes and hotspots in global terrestrial water storage (Pokhrel et al., 2021), environmental flows (Thompson et al., 2021), the planetary boundary for freshwater change (Porkka et al., 2024), uncertainties in the calculation of groundwater recharge (Reinecke et al., 2021), and the development of methodological frameworks to compare model ensembles (Gnann et al., 2023).

Here, we present a new sector in ISIMIP called the ISIMIP Groundwater Sector, which integrates models of the groundwater community that operate at regional (at least multiple km2, Gleeson and Paszkowski, 2014) to global scales and are committed to providing model simulations to this new sector. The Groundwater sector aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of groundwater representation in large-scale models, identify groundwater-related uncertainties, enhance the robustness of predictions regarding the impact of global change on groundwater and connected systems through model ensembles, and provide insight into how to most reliably and efficiently model groundwater on regional to global scales. The new Groundwater sector is a separate but complementary sector to the existing Global Water sector. To our knowledge, there are currently no long-term community efforts for a structured model intercomparison project for groundwater models. While studies have benchmarked different modeling approaches (e.g., Maxwell et al., 2014), compared model outputs (Reinecke et al., 2021, 2024), or collected information on where and how we model groundwater (Telteu et al., 2021; Zipper et al., 2023; Zamrsky et al., 2025), no effort yet aims at forcing different groundwater models with the same climate and human forcings for different scenarios.

Specifically, the ISIMIP Groundwater sector will compile a model ensemble that enables us to assess the impact of global change on various groundwater-related variables and quantify model and scenario-related uncertainties. These insights can then be used to quantify the impacts of global change on, for example, water availability and in relation to other sectors impacted by changes in groundwater. The new sector welcomes all models that are relevant to assessing the impacts of global change on groundwater-related variables. While the current set of models presented here focuses on different physical representations of groundwater, future developments could also include models that account for hydro-economic aspects of groundwater (e.g., Niazi et al., 2025; Kahil et al., 2025). The ISIMIP Groundwater sector has natural linkages with other ISIMIP sectors, such as Global Water, Water Quality, Regional Water, and Agriculture. This paper will highlight the connections between groundwater and different ISIMIP sectors, providing an opportunity to enhance our understanding of how modeling choices affect groundwater simulation dynamics.

In this manuscript, we provide an overview of the current ISIMIP framework with an emphasis on how the new sector is embedded in the current project in Sect. 2. The current generation of groundwater models participating in this effort is described and compared, and we define a list of output variables that form the foundation of the sector's model intercomparison protocol in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4, we showcase current model differences and possible future analysis. The connections to other sectors are discussed in Sect. 5, and Sect. 6 provides an outlook on future scientific goals for the groundwater sector.

ISIMIP aims to provide a framework for consistent climate impact data across sectors and scales. It facilitates model evaluation and improvement, enables climate change impact assessments across sectors, and provides robust projections of climate change impacts under different socioeconomic scenarios. ISIMIP uses a subset of bias-adjusted climate models from the CMIP6 ensemble. The subset is selected to represent the broader CMIP6 ensemble while maintaining computational feasibility for impact studies (Lange, 2021).

ISIMIP has undergone multiple phases, with the current phase being ISIMIP3. The simulation rounds consist of two main components: ISIMIP3a and ISIMIP3b, each serving distinct purposes. ISIMIP3a focuses on model evaluation and the attribution of observed climate impacts, covering the historical period up to 2021. It utilizes observational climate and socioeconomic data and includes a counterfactual “no climate change baseline” using detrended climate data for impact attribution. Additionally, ISIMIP3a includes sensitivity experiments with high-resolution historical climate forcing and water management sensitivity experiments. In contrast, ISIMIP3b aims to quantify climate-related risks under various future scenarios, covering pre-industrial, historical, and future projections. ISIMIP3b is divided into three groups: Group I for pre-industrial and historical periods, Group II for future projections with fixed 2015 direct human forcing, and Group III for future projections with changing socioeconomic conditions and representation of adaptation. Despite their differences in focus, time periods, and data sources, both ISIMIP3a and ISIMIP3b require the use of the same impact model version to ensure consistent interpretation of output data, thereby contributing to ISIMIP's overall goal of providing a framework for consistent climate impact data across sectors and scales.

The creation of a new ISIMIP Groundwater sector is not linked to any funding and is a community-driven effort that includes all modeling groups that wish to participate. During the creation process, multiple groups and institutions were contacted to participate, and additional modeling groups are welcome to join the sector in the future. Models participating in the sectors do not need to be able to model all variables and scenarios defined in the protocol. ISIMIP sectors can be linked to broader thematic concepts, such as Agriculture, or can focus on specific components of the Earth system, such as Lakes or Groundwater (see also https://www.isimip.org/about/#sectors-and-contacts, last access: 20 December 2025). The separation into these sectors is driven by the availability of models that can be integrated into a model-intercomparison framework, which is based on the same climatic and human forcings and produces a set of comparable output variables. We would like to note that groundwater is not an isolated system, but rather part of the water cycle and the Earth system as a whole. Focusing on it within a dedicated sector aligns well with the existing models and is useful for studying groundwater systems in a thematically focused way. Collaboration (and perhaps integration) with sectors like the Global Water sector is possible and desirable in the future. The global water sector focuses on using the ISIMIP protocol to drive a diverse set of global water models (including hydrological and land surface models; Reinecke et al., 2025a) and to produce output variables that capture diverse hydrologic processes, such as discharge, as well as human water use. We discuss possible future synergies with other existing ISIMIP sectors in Sect. 5.

In the short term, the Groundwater sector will focus on the historical period from 1901 to 2019 in ISIMIP3a (https://protocol.isimip.org/#/ISIMIP3a/water_global/groundwater, last access: 20 December 2025), using climate-related forcing based on observational data (obsclim) and the direct human forcing based on historical data (histsoc). We aim to use these simulations for an in-depth model comparison, including a comparison to observational data such as time series of water table depth (e.g., Jasechko et al., 2024) and by utilizing so-called functional relationships (Reinecke et al., 2024; Gnann et al., 2023). Functional relationships can be defined as covariations of variables across space and/or time, and they are a key aspect of our theoretical knowledge of Earth's functioning. Examples include relationships between precipitation and groundwater recharge (Gnann et al., 2023; Berghuijs et al., 2024) or between topographic slope and water table depth (Reinecke et al., 2024).

Carrying out the ISIMIP experiments in the groundwater sector will yield a new understanding of how these models differ, why they differ, and how they could be improved. These experiments will further help to disentangle the impacts of climate change and water management, specifically through ensemble runs of future scenarios using ISIMIP3 inputs.

Many large-scale groundwater models are already participating in the sector (Table 1), and we expect it to expand further. The current models are mainly global-scale, with some having a particular regional focus, and primarily using daily timesteps.

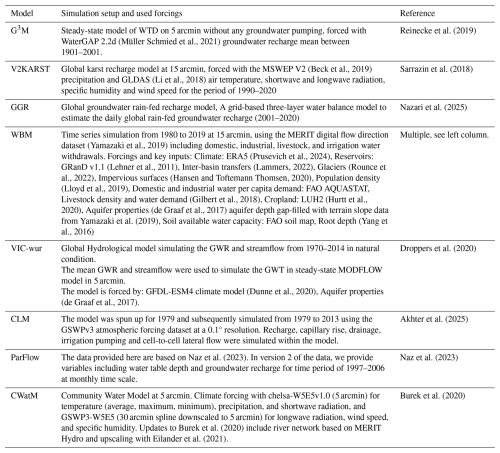

Table 1Summary of all models participating in the ISIMIP Groundwater sector. This table lists only models that add new variables to the ISIMIP protocol. Models already part of the global water sector and providing other groundwater-related variables are not listed here.

While the primary modeling purpose of most models is to simulate parts of the terrestrial water cycle, they all focus on different aspects (such as karst recharge or seawater intrusion), most investigate interactions between groundwater and land surface processes, and account for human water uses. Two models (V2KARST and GGR) have distinct purposes in modeling groundwater recharge and do not model any head-based groundwater fluxes. Conceptually, the models may be classified according to Condon et al. (2021) into five categories: (a) lumped models with static groundwater configurations of long-term mass balance, (b) saturated groundwater flow with recharge, and surface water exchange fluxes as upper boundary conditions without lateral fluxes, (c) quasi 3D models with variably saturated flow in the soil column and a dynamic water table as a lower boundary condition, (d) saturated flow models solving mainly the Darcy equation, (e) and variably saturated flow which is calculated as three-dimensional flow throughout the entire subsurface below and above the water table. See Condon et al. (2021) and also Gleeson et al. (2021) for a more detailed overview and discussion of approaches. Half of the models (Table 1) simulate a saturated subsurface flux (d), while V2KARST and GGR mainly use a 1D vertical approach (b), and others simulate a combination of multiple approaches (ParFlow, Table 1) or can switch between different approaches (CWatM, Table 1).

The sector protocol is defined at https://protocol.isimip.org/#/ISIMIP3a/groundwater (last access: 20 December 2025) and will be updated over time. We have defined multiple joint outputs for this sector (23 variables in total), but not all models can yet provide all outputs (Table 2). Models can provide 1–19 outputs (11 on average), and multiple models have additional outputs that are currently under development. The global water sector also contains groundwater-related variables (Table A2), enabling groundwater-related analysis. We list them here to show their close connection to the global water sector and facilitate an overview of future groundwater-related studies.

Table 2List of output variables in the ISIMIP3a Groundwater sector. The spatial resolution is five arcminutes (even if some models simulate at a higher or coarser resolution), and the temporal resolution is monthly. Most models also simulate daily timesteps, but as most groundwater movement happens across longer time scales, we unified the unit to months. A “*” indicates that a model is able to produce the necessary output. A “+” indicates that this output is currently under development.

The current sector protocol defines a targeted spatial resolution of 5 arcmin, as this represents not only the resolution achievable by most global models but also the coarsest resolution at which meaningful representation of groundwater dynamics, particularly lateral groundwater flows and water table depths, can still be captured (Gleeson et al., 2021). ISIMIP3 also specifies experiments with different spatial resolutions, but whether this is achievable with a sub-ensemble of the presented models remains unclear, as it depends on the available computational time, flexibility of model setups, and data availability. To ensure consistency and comparability, the model outputs are currently post-processed by the modeling groups to aggregate their outputs to the protocol-specified spatial and temporal resolutions.

The ISIMIP groundwater sector is in an early development stage, and we hope that an ensemble of groundwater models driven by the same meteorological data will be available soon. Yet, to provide first insights into the models, their outputs, and how these can be compared, we collected existing outputs from the participating models (see Table A1 for an overview). We opted for a straightforward initial comparison due to the various data formats, model resolutions, and forcings that complicate a more thorough examination of a specific scientific inquiry. One of our goals in the Groundwater sector is to conduct extensive analysis to better illustrate and understand the model differences. The analysis presented here is intended solely as an introductory overview to provide a sense of the rationale behind our initiative. Some overlap with recent model comparison studies naturally exists (e.g., Gnann et al., 2023; Reinecke et al., 2024, 2021); however, the presented analysis contains a different ensemble of models and thus provides new insights. Hence, this descriptive analysis serves as an introductory overview that highlights the present state of the art and identifies model discrepancies warranting further investigation. In addition, relevant output data are not yet available for all models. We focused on the two variables with the largest available ensemble: water table depth (G3M, CLM, WBM, and VIC-wur; Table 1) and groundwater recharge (CLM, CWatM, GGR, VIC-wur, V2KARST, WBM; Table 1), only on historical periods rather than future projections.

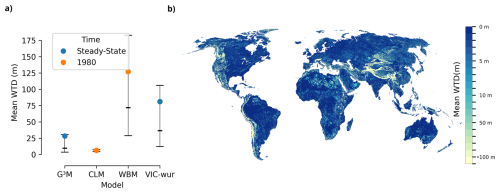

The arithmetic mean (not weighted by cell area) global water table depth varies substantially (6–127 m) between the models at the start of the simulation (1980 or steady-state) (Fig. 1a). On average, the water table of G3M (28 m) and CLM (6 m) are shallower than WBM (127 m) and VIC-wur (81 m), whereas the latter two also show a larger standard deviation (WBM: 133 m, VIC-wur: 105 m) than the other two models (G3M: 49 m, CLM: 3 m). The consistently shallower WTD of CLM impacts the ensemble mean WTD (Fig. 1b), which is shallower compared to other model ensembles (5.67 m WTD as global mean here compared to 7.03 m in Reinecke et al., 2024).

Figure 1Global water table depth (WTD) at simulation start (1980) or the used steady-state. The simplified boxplot (a) shows the arithmetic model mean as a colored dot and the median as a black line. Whiskers indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The global map (b) shows the arithmetic mean of the model ensemble. Models shown are not yet driven by the same meteorological forcing (see also Table A1).

This difference in ensemble WTD points to conceptual differences between the models. G3M and CLM both use the relatively shallow WTD estimates of Fan et al. (2013) as initial state or spin-up, which could explain the overall shallow water table depth. The difference between G3M and VIC-wur is consistent with the findings in Reinecke et al. (2024), which showed a deeper water table simulated by the de Graaf et al. (2017) groundwater model, which developed an aquifer parameterization adapted and conceptually similar to VIC-wur and WBM. This difference may be linked to the implementation of groundwater drainage/surface water infiltration or transmissivity parameterizations (Reinecke et al., 2024) as well as differences in groundwater recharge (Reinecke et al., 2021). Furthermore, the models are not yet driven by the same climatic and human forcings, thereby possibly causing different model responses. The newly initiated ISIMIP Groundwater sector offers an opportunity to investigate these differences much more systematically in future studies, for example, by ruling out forcing as a driver of the model differences and by exploring spatial and temporal relationships with key groundwater drivers such as topography (e.g., Reinecke et al., 2024). In addition, the ISIMIP Groundwater sector provides a platform for using the modelling team's expertise on their model implementations (e.g., model structures and parameter fields) to better understand the origins of these differences.

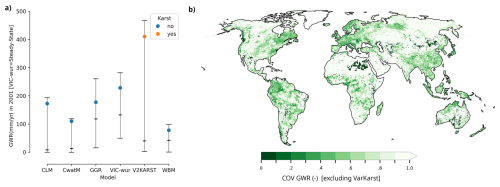

Similarly, the global arithmetic mean groundwater recharge (not weighted by cell area) differs by 332 mm yr−1 between models (150 mm yr−1 excluding V2KARST since it calculates recharge in karst regions only) (Fig. 2a). This difference in recharge is more pronounced spatially (Fig. 2b) than differences in WTD shown before (Fig. 1b). Especially in drier regions such as in the southern Africa, central Australia, and the northern latitudes show coefficient of variation of 1 or greater (white areas). In extremely dry areas such as the east Sahara and southern Australia, the model spread is close to 0 (dark green). While the agreement is higher in Europe and western South America, the global map differs slightly from other recent publications (e.g., compared to Fig. 1b in Gnann et al., 2023). In light of other publications, highlighting model uncertainty in groundwater recharge (Reinecke et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2025) and the possible impacts of long-term aridity changes on groundwater recharge (Berghuijs et al., 2024), an extended combined ensemble of the global water sector and the new Groundwater sector could yield valuable insights.

Figure 2Global groundwater recharge (GWR) in 2001 or at steady-state (only VIC-wur). The simplified boxplot (a) shows the arithmetic model mean as a colored dot and the median as a black line. Whiskers indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The global map (b) shows the coefficient of variation of the model ensemble without V2KARST calculated as the ensemble standard deviation divided by the ensemble mean. Models shown are not yet driven by the same meteorological forcing (see also Table A1).

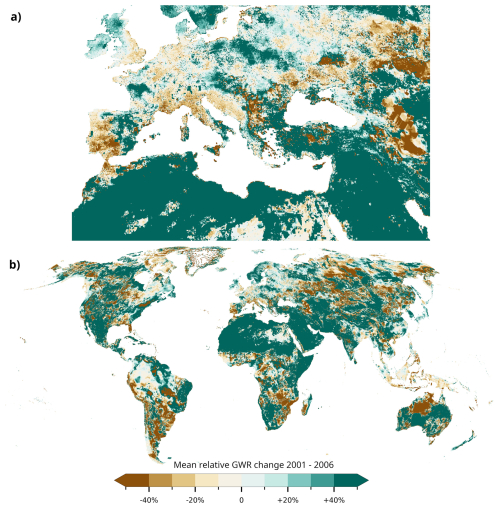

We further calculated relative changes in groundwater recharge between 2001 and 2006 (Fig. 3) with an ensemble of 7 models (CLM, CWatM, GGR, VIC-wur, V2KARST, WBM, and ParFlow). The ensemble includes two models that only simulate specific regions (V2KARST: regions of karstifiable rock, ParFlow: Euro CORDEX domain). This result shows a potential analysis that should be repeated within the new Groundwater sector. Intentionally, we do not investigate model agreement on the sign of change or compare them with observed data. The ensemble still highlights plausible regions of groundwater recharge changes, such as in Spain and Portugal, which aligns with droughts in the investigated period (Paneque Salgado and Vargas Molina, 2015; Coll et al., 2017; Trullenque-Blanco et al., 2024). Relative increases in groundwater recharge are mainly shown for arid regions in the Sahara, the Middle East, Australia, and Mexico. However, it is likely that because we investigate relative changes, this might be related to the already low recharge rates in these regions.

Figure 3Mean relative percentage change of yearly groundwater recharge between 2001 and 2006 for Europe (a), and all continents except Antarctica (b). The ensemble consists of all models that provided data for the years 2001 and 2006 (CLM, CWatM, GGR, VIC-wur, V2KARST, WBM, and ParFlow). V2KARST (only karst) and ParFlow (only Euro CORDEX domain) were only accounted for in regions where data is available. Models shown are not yet driven by the same meteorological forcing (see also Table A1).

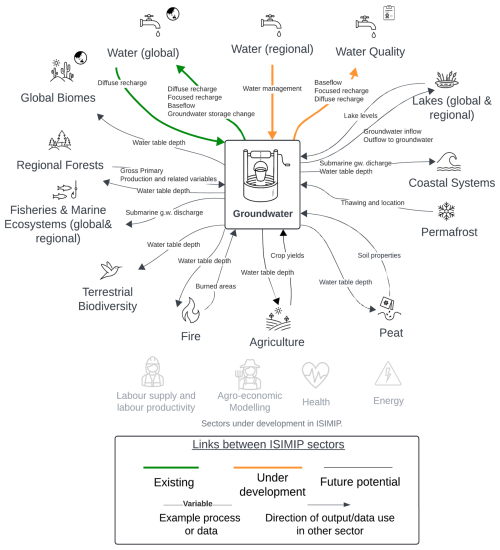

ISIMIP encompasses a wide variety of sectors. Currently, 18 sectors are part of the impact assessment effort. The Groundwater sector offers a new and unique opportunity to enhance cross-sectoral activities within ISIMIP, foster interlinkages within ISIMIP, and thus deliver interdisciplinary assessments of climate change impacts.

Some links with other sectors within ISIMIP are more evident than others with regard to existing scientific community overlaps or existing scientific questions (Fig. 4). The examples of variables and data that can be shared among sectors shown in Fig. 4 provide a non-exhaustive description of current variables that the sectors already describe in their protocols. Whether cross-sectoral assessments will utilize this available data is up to the modeling teams that contribute to the sectors. For example, the new Groundwater sector will focus on large-scale groundwater models, some of which are already part of global water models participating in the Global Water Sector or using outputs (such as groundwater recharge) from the Global Water Sector (see also existing groundwater variables in the global water sector Table A2). However, the Groundwater sector will also feature non-global representations of groundwater. Thus, collaborating with the Regional Water sector could provide opportunities to share outputs and pursue common assessments. For example, the outputs of the groundwater model ensemble, such as water table depth variations or surface water groundwater interactions, could be used as input for some regional models that consider groundwater only as a lumped groundwater storage. Conversely, global and continental groundwater models can benefit from validated regional hydrological models, which may provide valuable insights into local runoff generation processes and the impacts of water management.

Figure 4The Groundwater sector provides the potential for multiple interlinkages between different sectors within ISIMIP. In the coming years, we will focus on links to three sectors (green and orange): Water (global), Water (regional), and Water Quality. Other cross-sectoral linkages between non-Groundwater sectors (i.e., linkages between the outer circle) are not shown. Sectors that are currently under development or have not yet have data or outputs that could be shared or used for cross-sectoral assessments are shown in gray. Interactions between sectors are annotated with example processes, key variables, or datasets that can be shared between sectors.

Furthermore, the relevance of groundwater for water quality assessments is widely recognized (e.g., for phosphorous transport from groundwater to surface water; Holman et al., 2008), or for salinization (Kretschmer et al., 2025), or as a link between warming groundwater and stream temperatures (Benz et al., 2024). And the community effort of Friends of Groundwater called for a global assessment of groundwater quality (Misstear et al., 2023). The Water Quality sector could incorporate model outputs from the Groundwater sector as input to improve, for example, their estimates of groundwater contributions to surface water quantity or leakage of surface water to groundwater. On the other hand, the Groundwater sector can utilize estimates of the Water Quality sector to better assess water availability by incorporating water quality criteria. Ultimately, this may also result in advanced groundwater models in the Groundwater sector that account for quality-related processes directly, which can then be integrated into a future modeling protocol. One of the models (G3M; see Table 1) is already capable of simulating salinization processes.

Leveraging such connections between sectors will provide valuable insights beyond groundwater itself. The outputs and models that can be used for intersectoral assessments depend on the research question and may necessitate the use of only a subset of models from an ensemble. Specifically, considering groundwater quality, a collaboration between both sectors could be achieved in multiple aspects. Integrating groundwater availability with water quality helps ensure sufficient and safe drinking and irrigation water. Focusing on aquifer storage levels and pollutant loads can help maintain groundwater resilience, safeguard food security, and protect public health under changing climate and socioeconomic conditions. Further, integrating groundwater quantity data with pollution source mapping helps prioritize remediation efforts where aquifers are most vulnerable, ensuring both water availability and quality. Concerning observational data, a unified approach to collecting and developing shared databases for groundwater levels and water quality measurements across multiple agencies reduces bureaucratic hurdles and ensures consistent, comparable data. Using standardized procedures for dealing with observational uncertainties, such as data gaps, scaling issues, and measurement inconsistencies, would support collaborative research further.

Research opportunities arise in other sectors as well. Groundwater is connected to the water cycle and social, economic, and ecological systems (Huggins et al., 2023). For example, health impacts (such as water- and vector-borne diseases) are closely related to water quantity and quality (e.g. Smith et al., 2024), and the roles of groundwater for forest resilience (regional forest sector, Costa et al., 2023; Esteban et al., 2021) and forest fires (fire sector) under climate change are yet to be explored (Fig. 4). To prioritize our efforts and set a research agenda for the groundwater ISIMIP sector, we will first focus on existing and more straightforward connections to the global water sector, regional water sector, and the water quality sector and then expand to collaboration with other sectors (Fig. 4).

Given groundwater's importance in the Earth system and for society, it is imperative to expand our knowledge of groundwater and (1) how it is impacted by climate change and other human forcings and (2) how, in turn, this will affect other systems connected to groundwater. This enhanced understanding is essential to equip us with the knowledge needed to address future challenges effectively. The ISIMIP Groundwater sector serves as a foundation for examining and measuring the effects of global change on groundwater systems worldwide. It facilitates cross-sector investigations, such as those concerning water quality, examines the influence of various model structures on groundwater dynamics simulations, and supports the collaborative creation of new datasets for model parameterization and assessment. Other intercomparison and impact assessment projects already have been successful in achieving similar goals such as the lake (Golub et al., 2022) or water quality sector (Strokal et al., 2025) in ISIMIP, the CMIP (Eyring et al., 2016a), or the AgMIP for agricultural models (von Lampe et al., 2014).

Already in the short term, the creation of the Groundwater sector has substantial potential to enhance large-scale groundwater research by developing better modeling frameworks for reproducible research (running the multitude of experiments targeted in ISIMIP requires an automated modeling pipeline) and forge a community that can critically examine current modeling practices. The simple model comparison presented raises initial questions as to why models differ and invites us to explore model differences in greater depth. Such model intercomparison studies will enable us to quantify uncertainties and identify hotspots for model improvement. They will also allow us to assess the impact of climate and land use change on various groundwater-related variables, such as groundwater recharge and water table depth, and enable ensemble-based impact assessments of future water availability. Model intercomparison and validation may also help identify models that perform better in specific regions or for specific output variables, thus allowing the provision of region- or variable-specific recommendations and uncertainty assessments to subsequent data users.

In the long term, the sector will enable us to jointly reflect on processes that we currently do not model or that require improvement, possibly also through new modeling approaches such as hybrid machine-learning models tailored to the large-scale representation of groundwater. These model developments will be incorporated into the groundwater sector's contributions to upcoming ISIMIP simulation rounds, such as ISIMIP4, which is scheduled to commence in 2026. Since groundwater is connected to many socio-ecological systems, groundwater models could also emerge as a modular coupling tool that can be integrated into multiple sectors. The newly established groundwater sector already provides a first step in that direction by standardizing output names and units. If models are modular enough and define a standardized Application Programming Interface (API), they could also serve as a valuable tool for other science communities.

The lack of a community-wide coordinated effort to simulate the effects of climate change on groundwater at regional to global scale has precluded the comprehensive consideration of climate change impacts on groundwater in policy relevant reports, such as the European Climate risk assessment (European Environment Agency,, 2024) or the Assessment Reports developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (e.g. IPCC, 2023). The anticipated groundwater sector contributions to ISIMIP3 and ISIMIP4, as described here, will address this gap by serving as scientific evidence in the second EUCRA round and the upcoming IPCC seventh assessment cycle. As such, the anticipated outcomes of the new sector will pave the way for groundwater simulations to play an increasingly important role in international climate mitigation and adaptation policy.

In summary, the ISIMIP Groundwater sector aims to enhance our understanding of the impacts of climate change and direct human impacts on groundwater and a range of related sectors. To realize this goal, the new ISIMIP Groundwater sector will address numerous challenges. For instance, core simulated variables, such as water table depth and recharge, are highly uncertain and difficult to compare with observations. Further, tracing down explanations for inter-model differences will require the joint development and application of new evaluation methods (Eyring et al., 2016b) and protocols. Currently, models of the Groundwater sector operate at different spatial resolutions, and compared to other sectors, they often run at relatively high spatial resolutions, which will need to be addressed in evaluation and analysis approaches. Furthermore, depending on the model, executing single-model simulations already requires substantial amounts of computation time, and running all impact scenarios may be infeasible for some modeling groups. Lastly, running simulations for ISIMIP requires not only computational resources but also human resources, which might not be feasible for all groups. This has always been the case with ISIMIP, and it is an issue that other sectors have faced as well. Still, we are confident that the groundwater sector will enhance our understanding of groundwater within the Earth system and help to promote dialogue and synthesis in the research community. With its various connections to other sectors, the Groundwater sector can be a catalyst for developing new holistic cross-sector modelling efforts that account for the multitude of interconnections between the water cycle and social, economic, and ecological systems.

Table A2List of groundwater related output variables in the ISIMIP3a global water sector (https://protocol.isimip.org/#/ISIMIP3a/water_global, last access: 20 December 2025). The unit of all variables is , the spatial resolution is 0.5° grid and the temporal resolution is monthly.

The ensemble-mean WTD and groundwater recharge trends are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14962511 (Reinecke et al., 2025b). The Zenodo repository included pre-processing scripts, plotting files, and data, as well as the main outputs presented in this manuscript as raster files. For the original model data publications, see Table A1.

RR led the writing and analysis of the manuscript. RR and IdG conceived the idea. All authors reviewed the manuscript and provided suggestions on text and figures.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This open-access publication was funded by Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz.

This paper was edited by Thomas B. Wild and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Akhter, T., Pokhrel, Y., Felfelani, F., Ducharne, A., Lo, M.-H., and Reinecke, R.: Implications of lateral groundwater flow across varying spatial resolutions in global land surface modeling, Water Resources Research, 61, e2024WR038523, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024WR038523, 2025.

Beck, H. E., Wood, E. F., Pan, M., Fisher, C. K., Miralles, D. G., van Dijk, A. I. J. M., McVicar, T. R., and Adler, R. F.: MSWEP V2 Global 3-Hourly 0.1° Precipitation: Methodology and Quantitative Assessment, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 100, 473–500, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-17-0138.1, 2019.

Benz, S. A., Irvine, D. J., Rau, G. C., Bayer, P., Menberg, K., Blum, P., Jamieson, R. C., Griebler, C., and Kurylyk, B. L.: Global groundwater warming due to climate change, Nature Geoscience, 17, 545–551, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01453-x, 2024.

Berghuijs, W. R., Collenteur, R. A., Jasechko, S., Jaramillo, F., Luijendijk, E., Moeck, C., van der Velde, Y., and Allen, S. T.: Groundwater recharge is sensitive to changing long-term aridity, Nature Climate Change, 14, 357–363, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-01953-z, 2024.

Bierkens, M. and Wada, Y.: Non-renewable groundwater use and groundwater depletion: a review, Environ. Res. Lett., 14, 63002, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab1a5f, 2019.

Burek, P., Satoh, Y., Kahil, T., Tang, T., Greve, P., Smilovic, M., Guillaumot, L., Zhao, F., and Wada, Y.: Development of the Community Water Model (CWatM v1.04) – a high-resolution hydrological model for global and regional assessment of integrated water resources management, Geoscientific Model Development, 13, 3267–3298, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-3267-2020, 2020.

Coll, J. R., Aguilar, E., and Ashcroft, L.: Drought variability and change across the Iberian Peninsula, Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 130, 901–916, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-016-1926-3, 2017.

Condon, L. E. and Maxwell, R. M.: Simulating the sensitivity of evapotranspiration and streamflow to large-scale groundwater depletion, Science Advances, 5, eaav4574, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav4574, 2019.

Condon, L. E., Kollet, S., Bierkens, M. F. P., Fogg, G. E., Maxwell, R. M., Hill, M. C., Fransen, H.-J. H., Verhoef, A., van Loon, A. F., Sulis, M., and Abesser, C.: Global Groundwater Modeling and Monitoring: Opportunities and Challenges, Water Resources Research, 57, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR029500, 2021.

Costa, F. R. C., Schietti, J., Stark, S. C., and Smith, M. N.: The other side of tropical forest drought: do shallow water table regions of Amazonia act as large-scale hydrological refugia from drought?, The New Phytologist, 237, 714–733, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17914, 2023.

Cuthbert, M. O., Gleeson, T., Moosdorf, N., Befus, K. M., Schneider, A., Hartmann, J., and Lehner, B.: Global patterns and dynamics of climate-groundwater interactions, Nature Climate Change, 9, 137–141, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0386-4, 2019.

Cuthbert, M. O., Gleeson, T., Bierkens, M. F. P., Ferguson, G., and Taylor, R. G.: Defining renewable groundwater use and its relevance to sustainable groundwater management, Water Resources Research, 59, e2022WR032831, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022WR032831, 2023.

Dalin, C., Wada, Y., Kastner, T., and Puma, M. J.: Groundwater depletion embedded in international food trade, Nature, 543, 700–704, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21403, 2017.

de Graaf, I., van Beek, R. L. P. H., Gleeson, T., Moosdorf, N., Schmitz, O., Sutanudjaja, E. H., and Bierkens, M. F. P.: A global-scale two-layer transient groundwater model: Development and application to groundwater depletion, Advances in Water Resources, 102, 53–67, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2017.01.011, 2017.

de Graaf, I. E. M., Sutanudjaja, E. H., van Beek, L. P. H., and Bierkens, M. F. P.: A high-resolution global-scale groundwater model, Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 19, 823–837, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-19-823-2015, 2015.

de Graaf, I. E. M., Gleeson, T., van Rens Beek, L. P. H., Sutanudjaja, E. H., and Bierkens, M. F. P.: Environmental flow limits to global groundwater pumping, Nature, 574, 90–94, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1594-4, 2019.

Döll, P. and Siebert, S.: Global modeling of irrigation water requirements, Water Resources Research, 38, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001WR000355, 2002.

Droppers, B., Franssen, W. H. P., van Vliet, M. T. H., Nijssen, B., and Ludwig, F.: Simulating human impacts on global water resources using VIC-5, Geoscientific Model Development, 13, 5029–5052, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-5029-2020, 2020.

Droppers, B., Supit, I., van Vliet, M. T. H., and Ludwig, F.: Worldwide water constraints on attainable irrigated production for major crops, Environ. Res. Lett., 16, 055016, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abf527, 2021.

Dunne, J. P., Horowitz, L. W., Adcroft, A. J., Ginoux, P., Held, I. M., John, J. G., Krasting, J. P., Malyshev, S., Naik, V., Paulot, F., Shevliakova, E., Stock, C. A., Zadeh, N., Balaji, V., Blanton, C., Dunne, K. A., Dupuis, C., Durachta, J., Dussin, R., Gauthier, P. P. G., Griffies, S. M., Guo, H., Hallberg, R. W., Harrison, M., He, J., Hurlin, W., McHugh, C., Menzel, R., Milly, P. C. D., Nikonov, S., Paynter, D. J., Ploshay, J., Radhakrishnan, A., Rand, K., Reichl, B. G., Robinson, T., Schwarzkopf, D. M., Sentman, L. T., Underwood, S., Vahlenkamp, H., Winton, M., Wittenberg, A. T., Wyman, B., Zeng, Y., and Zhao, M.: The GFDL Earth System Model Version 4.1 (GFDL-ESM 4.1): Overall Coupled Model Description and Simulation Characteristics, Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, 12, e2019MS002015, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS002015, 2020.

Eilander, D., van Verseveld, W., Yamazaki, D., Weerts, A., Winsemius, H. C., and Ward, P. J.: A hydrography upscaling method for scale-invariant parametrization of distributed hydrological models, Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 25, 5287–5313, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-5287-2021, 2021.

Esteban, E. J. L., Castilho, C. V., Melgaço, K. L., and Costa, F. R. C.: The other side of droughts: wet extremes and topography as buffers of negative drought effects in an Amazonian forest, The New Phytologist, 229, 1995–2006, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17005, 2021.

European Environment Agency: European Climate Risk Assessment, EEA Report 01/2024, European Environment Agency, Luxembourg, ISBN 978-92-9480-678-9, https://doi.org/10.2800/8671471, 2024.

Eyring, V., Bony, S., Meehl, G. A., Senior, C. A., Stevens, B., Stouffer, R. J., and Taylor, K. E.: Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization, Geoscientific Model Development, 9, 1937–1958, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-1937-2016, 2016a.

Eyring, V., Righi, M., Lauer, A., Evaldsson, M., Wenzel, S., Jones, C., Anav, A., Andrews, O., Cionni, I., Davin, E. L., Deser, C., Ehbrecht, C., Friedlingstein, P., Gleckler, P., Gottschaldt, K.-D., Hagemann, S., Juckes, M., Kindermann, S., Krasting, J., Kunert, D., Levine, R., Loew, A., Mäkelä, J., Martin, G., Mason, E., Phillips, A. S., Read, S., Rio, C., Roehrig, R., Senftleben, D., Sterl, A., van Ulft, L. H., Walton, J., Wang, S., and Williams, K. D.: ESMValTool (v1.0) – a community diagnostic and performance metrics tool for routine evaluation of Earth system models in CMIP, Geoscientific Model Development, 9, 1747–1802, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-1747-2016, 2016b.

Fan, Y., Li, H., and Miguez-Macho, G.: Global patterns of groundwater table depth, Science, 339, 940–943, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1229881, 2013.

Felfelani, F., Lawrence, D. M., and Pokhrel, Y.: Representing Intercell Lateral Groundwater Flow and Aquifer Pumping in the Community Land Model, Water Resources Research, 57, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR027531, 2021.

Foster, S. S. D. and Chilton, P. J.: Groundwater: the processes and global significance of aquifer degradation, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 358, 1957–1972, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2003.1380, 2003.

Frieler, K., Lange, S., Piontek, F., Reyer, C. P. O., Schewe, J., Warszawski, L., Zhao, F., Chini, L., Denvil, S., Emanuel, K., Geiger, T., Halladay, K., Hurtt, G., Mengel, M., Murakami, D., Ostberg, S., Popp, A., Riva, R., Stevanovic, M., Suzuki, T., Volkholz, J., Burke, E., Ciais, P., Ebi, K., Eddy, T. D., Elliott, J., Galbraith, E., Gosling, S. N., Hattermann, F., Hickler, T., Hinkel, J., Hof, C., Huber, V., Jägermeyr, J., Krysanova, V., Marcé, R., Müller Schmied, H., Mouratiadou, I., Pierson, D., Tittensor, D. P., Vautard, R., van Vliet, M., Biber, M. F., Betts, R. A., Bodirsky, B. L., Deryng, D., Frolking, S., Jones, C. D., Lotze, H. K., Lotze-Campen, H., Sahajpal, R., Thonicke, K., Tian, H., and Yamagata, Y.: Assessing the impacts of 1.5 °C global warming – simulation protocol of the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP2b), Geoscientific Model Development, 10, 4321–4345, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-10-4321-2017, 2017.

Frieler, K., Volkholz, J., Lange, S., Schewe, J., Mengel, M., del Rocío Rivas López, M., Otto, C., Reyer, C. P. O., Karger, D. N., Malle, J. T., Treu, S., Menz, C., Blanchard, J. L., Harrison, C. S., Petrik, C. M., Eddy, T. D., Ortega-Cisneros, K., Novaglio, C., Rousseau, Y., Watson, R. A., Stock, C., Liu, X., Heneghan, R., Tittensor, D., Maury, O., Büchner, M., Vogt, T., Wang, T., Sun, F., Sauer, I. J., Koch, J., Vanderkelen, I., Jägermeyr, J., Müller, C., Rabin, S., Klar, J., Vega del Valle, I. D., Lasslop, G., Chadburn, S., Burke, E., Gallego-Sala, A., Smith, N., Chang, J., Hantson, S., Burton, C., Gädeke, A., Li, F., Gosling, S. N., Müller Schmied, H., Hattermann, F., Wang, J., Yao, F., Hickler, T., Marcé, R., Pierson, D., Thiery, W., Mercado-Bettín, D., Ladwig, R., Ayala-Zamora, A. I., Forrest, M., and Bechtold, M.: Scenario setup and forcing data for impact model evaluation and impact attribution within the third round of the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP3a), Geosci. Model Dev., 17, 1–51, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-1-2024, 2024.

Gasper, F., Goergen, K., Shrestha, P., Sulis, M., Rihani, J., Geimer, M., and Kollet, S.: Implementation and scaling of the fully coupled Terrestrial Systems Modeling Platform (TerrSysMP v1.0) in a massively parallel supercomputing environment – a case study on JUQUEEN (IBM Blue Gene/Q), Geoscientific Model Development, 7, 2531–2543, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-7-2531-2014, 2014.

Gilbert, M., Nicolas, G., Cinardi, G., van Boeckel, T. P., Vanwambeke, S. O., Wint, G. R. W., and Robinson, T. P.: Global distribution data for cattle, buffaloes, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, chickens and ducks in 2010, Scientific Data, 5, 180227, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.227, 2018.

Gisser, M. and Sánchez, D. A.: Competition versus optimal control in groundwater pumping, Water Resources Research, 16, 638–642, https://doi.org/10.1029/WR016i004p00638, 1980.

Gleeson, T. and Paszkowski, D.: Perceptions of scale in hydrology: what do you mean by regional scale?, Hydrological Sciences Journal, 59, 99–107, https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2013.797581, 2014.

Gleeson, T., Cuthbert, M., Ferguson, G., and Perrone, D.: Global Groundwater Sustainability, Resources, and Systems in the Anthropocene, Annual Review Earth and Planetary Sciences, 48, 431–463, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-071719-055251, 2020.

Gleeson, T., Wagener, T., Döll, P., Zipper, S. C., West, C., Wada, Y., Taylor, R., Scanlon, B., Rosolem, R., Rahman, S., Oshinlaja, N., Maxwell, R., Lo, M.-H., Kim, H., Hill, M., Hartmann, A., Fogg, G., Famiglietti, J. S., Ducharne, A., de Graaf, I., Cuthbert, M., Condon, L., Bresciani, E., and Bierkens, M. F. P.: GMD perspective: The quest to improve the evaluation of groundwater representation in continental- to global-scale models, Geoscientific Model Development, 14, 7545–7571, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-14-7545-2021, 2021.

Gnann, S., Reinecke, R., Stein, L., Wada, Y., Thiery, W., Müller Schmied, H., Satoh, Y., Pokhrel, Y., Ostberg, S., Koutroulis, A., Hanasaki, N., Grillakis, M., Gosling, S., Burek, P., Bierkens, M., and Wagener, T.: Functional relationships reveal differences in the water cycle representation of global water models, Nature Water, 1079–1090, https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-023-00160-y, 2023.

Golub, M., Thiery, W., Marcé, R., Pierson, D., Vanderkelen, I., Mercado-Bettin, D., Woolway, R. I., Grant, L., Jennings, E., Kraemer, B. M., Schewe, J., Zhao, F., Frieler, K., Mengel, M., Bogomolov, V. Y., Bouffard, D., Côté, M., Couture, R.-M., Debolskiy, A. V., Droppers, B., Gal, G., Guo, M., Janssen, A. B. G., Kirillin, G., Ladwig, R., Magee, M., Moore, T., Perroud, M., Piccolroaz, S., Raaman Vinnaa, L., Schmid, M., Shatwell, T., Stepanenko, V. M., Tan, Z., Woodward, B., Yao, H., Adrian, R., Allan, M., Anneville, O., Arvola, L., Atkins, K., Boegman, L., Carey, C., Christianson, K., de Eyto, E., DeGasperi, C., Grechushnikova, M., Hejzlar, J., Joehnk, K., Jones, I. D., Laas, A., Mackay, E. B., Mammarella, I., Markensten, H., McBride, C., Özkundakci, D., Potes, M., Rinke, K., Robertson, D., Rusak, J. A., Salgado, R., van der Linden, L., Verburg, P., Wain, D., Ward, N. K., Wollrab, S., and Zdorovennova, G.: A framework for ensemble modelling of climate change impacts on lakes worldwide: the ISIMIP Lake Sector, Geoscientific Model Development, 15, 4597–4623, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-15-4597-2022, 2022.

Grogan, D. S., Zuidema, S., Prusevich, A., Wollheim, W. M., Glidden, S., and Lammers, R. B.: Water balance model (WBM) v.1.0.0: a scalable gridded global hydrologic model with water-tracking functionality, Geoscientific Model Development, 15, 7287–7323, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-15-7287-2022, 2022.

Guillaumot, L., Smilovic, M., Burek, P., de Bruijn, J., Greve, P., Kahil, T., and Wada, Y.: Coupling a large-scale hydrological model (CWatM v1.1) with a high-resolution groundwater flow model (MODFLOW 6) to assess the impact of irrigation at regional scale, Geoscientific Model Development, 15, 7099–7120, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-15-7099-2022, 2022.

Hansen, M. and Toftemann Thomsen, C.: An integrated public information system for geology, groundwater and drinking water in Denmark, GEUS Bulletin, 38, 69–72, https://doi.org/10.34194/geusb.v38.4423, 2020.

Haqiqi, I., Bowling, L., Jame, S., Baldos, U., Liu, J., and Hertel, T.: Global drivers of local water stresses and global responses to local water policies in the United States, Environmental Research Letters, 18, 65007, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/acd269, 2023.

Hartmann, A. Gleeson, T., Wada, Y., and Wagener, T.: Enhanced groundwater recharge rates and altered recharge sensitivity to climate variability through subsurface heterogeneity, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114, 2842–2847, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1614941114, 2017.

Holman, I. P., Whelan, M. J., Howden, N. J. K., Bellamy, P. H., Willby, N. J., Rivas-Casado, M., and McConvey, P.: Phosphorus in groundwater – an overlooked contributor to eutrophication?, Hydrological Processes, 22, 5121–5127, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.7198, 2008.

Huggins, X., Gleeson, T., Castilla-Rho, J., Holley, C., Re, V., and Famiglietti, J. S.: Groundwater Connections and Sustainability in Social-Ecological Systems, Ground Water, 61, 463–478, https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.13305, 2023.

Hurtt, G. C., Chini, L., Sahajpal, R., Frolking, S., Bodirsky, B. L., Calvin, K., Doelman, J. C., Fisk, J., Fujimori, S., Klein Goldewijk, K., Hasegawa, T., Havlik, P., Heinimann, A., Humpenöder, F., Jungclaus, J., Kaplan, J. O., Kennedy, J., Krisztin, T., Lawrence, D., Lawrence, P., Ma, L., Mertz, O., Pongratz, J., Popp, A., Poulter, B., Riahi, K., Shevliakova, E., Stehfest, E., Thornton, P., Tubiello, F. N., van Vuuren, D. P., and Zhang, X.: Harmonization of global land use change and management for the period 850–2100 (LUH2) for CMIP6, Geoscientific Model Development, 13, 5425–5464, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-5425-2020, 2020.

IPCC: Summary for Policymakers, in: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Core Writing Team, Lee, H., and Romero, J., IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 1–34, https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.001, 2023.

Jasechko, S., Seybold, H., Perrone, D., Fan, Y., Shamsudduha, M., Taylor, R. G., Fallatah, O., and Kirchner, J. W.: Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally, Nature, 625, 715–721, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06879-8, 2024.

Kahil, T., Baccour, S., Joseph, J., Sahu, R., Burek, P., Ng, J. Y., Asad, S., Fridman, D., Albiac, J., Ward, F. A., and Wada, Y.: Development of the global hydro-economic model (ECHO-Global version 1.0) for assessing the performance of water management options, Geoscientific Model Development, 18, 7987–8015, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-18-7987-2025, 2025.

Keune, J., Sulis, M., Kollet, S., Siebert, S., and Wada, Y.: Human Water Use Impacts on the Strength of the Continental Sink for Atmospheric Water, Geophysical Research Letters, 45, 4068–4076, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL077621, 2018.

Kollet, S. J. and Maxwell, R. M.: Capturing the influence of groundwater dynamics on land surface processes using an integrated, distributed watershed model, Water Resources Research, 44, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007WR006004, 2008.

Konar, M., Hussein, Z., Hanasaki, N., Mauzerall, D. L., and Rodriguez-Iturbe, I.: Virtual water trade flows and savings under climate change, Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 17, 3219–3234, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-3219-2013, 2013.

Kretschmer, D. V., Michael, H., Moosdorf, N., Essink, G. O., Bierkens, M. F. P., Wagener, T., and Reinecke, R.: Controls on coastal saline groundwater across North America, Environmental Research Letters, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ada973, 2025.

Kuffour, B. N. O., Engdahl, N. B., Woodward, C. S., Condon, L. E., Kollet, S., and Maxwell, R. M.: Simulating coupled surface–subsurface flows with ParFlow v3.5.0: capabilities, applications, and ongoing development of an open-source, massively parallel, integrated hydrologic model, Geoscientific Model Development, 13, 1373–1397, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-1373-2020, 2020.

Kumar, R., Samaniego, L., Thober, S., Rakovec, O., Marx, A., Wanders, N., Pan, M., Hesse, F. and Attinger, S.: Multi-model assessment of groundwater recharge across Europe under warming climate, Earth's Future, 13, e2024EF005020, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024EF005020, 2025.

Lammers, R. B.: Global Inter-Basin Hydrological Transfer Database, https://doi.org/10.57931/1905995, 2022.

Lange, S.: Bias-correction fact sheet, https://www.isimip.org/gettingstarted/isimip3b-bias-adjustment/ (last access: 2 March 2025), 2021.

Lawrence, D. M., Fisher, R. A., Koven, C. D., Oleson, K. W., Swenson, S. C., Bonan, G., Collier, N., Ghimire, B., van Kampenhout, L., Kennedy, D., Kluzek, E., Lawrence, P. J., Li, F., Li, H., Lombardozzi, D., Riley, W. J., Sacks, W. J., Shi, M., Vertenstein, M., Wieder, W. R., Xu, C., Ali, A. A., Badger, A. M., Bisht, G., van den Broeke, M., Brunke, M. A., Burns, S. P., Buzan, J., Clark, M., Craig, A., Dahlin, K., Drewniak, B., Fisher, J. B., Flanner, M., Fox, A. M., Gentine, P., Hoffman, F., Keppel-Aleks, G., Knox, R., Kumar, S., Lenaerts, J., Leung, L. R., Lipscomb, W. H., Lu, Y., Pandey, A., Pelletier, J. D., Perket, J., Randerson, J. T., Ricciuto, D. M., Sanderson, B. M., Slater, A., Subin, Z. M., Tang, J., Thomas, R. Q., Val Martin, M., and Zeng, X.: The Community Land Model Version 5: Description of New Features, Benchmarking, and Impact of Forcing Uncertainty, Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, 11, 4245–4287, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018MS001583, 2019.

Lehner, B., Liermann, C. R., Revenga, C., Vörösmarty, C., Fekete, B., Crouzet, P., Döll, P., Endejan, M., Frenken, K., Magome, J., Nilsson, C., Robertson, J. C., Rödel, R., Sindorf, N., and Wisser, D.: High-resolution mapping of the world's reservoirs and dams for sustainable river-flow management, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 9, 494–502, https://doi.org/10.1890/100125, 2011.

Li, B., Rodell, M., and Beaudoing, H.: GLDAS Catchment Land Surface Model L4 daily 0.25×0.25 degree, Version 2.0, https://doi.org/10.5067/LYHA9088MFWQ, 2018.

Liang, X., Lettenmaier, D. P., Wood, E. F., and Burges, S. J.: A simple hydrologically based model of land surface water and energy fluxes for general circulation models, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 99, 14415–14428, https://doi.org/10.1029/94JD00483, 1994.

Liu, Y., Wagener, T., Beck, H. E., and Hartmann, A.: What is the hydrologically effective area of a catchment?, Environmental Research Letters, 15, 104024, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aba7e5, 2020.

Lloyd, C. T., Chamberlain, H., Kerr, D., Yetman, G., Pistolesi, L., Stevens, F. R., Gaughan, A. E., Nieves, J. J., Hornby, G., MacManus, K., Sinha, P., Bondarenko, M., Sorichetta, A., and Tatem, A. J.: Global spatio-temporally harmonised datasets for producing high-resolution gridded population distribution datasets, Big Earth Data, 3, 108–139, https://doi.org/10.1080/20964471.2019.1625151, 2019.

Maxwell, R. M. and Miller, N. L.: Development of a Coupled Land Surface and Groundwater Model, Journal of Hydrometeorology, 6, 233–247, https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM422.1, 2005.

Maxwell, R. M., Lundquist, J. K., Mirocha, J. D., Smith, S. G., Woodward, C. S., and Tompson, A. F. B.: Development of a Coupled Groundwater–Atmosphere Model, Monthly Weather Review, 139, 96–116, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010MWR3392.1, 2011.

Maxwell, R. M., Putti, M., Meyerhoff, S., Delfs, J.-O., Ferguson, I. M., Ivanov, V., Kim, J., Kolditz, O., Kollet, S. J., Kumar, M., Lopez, S., Niu, J., Paniconi, C., Park, Y.-J., Phanikumar, M. S., Shen, C., Sudicky, E. A., and Sulis, M.: Surface-subsurface model intercomparison: A first set of benchmark results to diagnose integrated hydrology and feedbacks, Water Resources Research, 50, 1531–1549, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR013725, 2014.

Maxwell, R. M., Condon, L. E., Kollet, S. J., Maher, K., Haggerty, R., and Forrester, M. M.: The imprint of climate and geology on the residence times of groundwater, Geophys. Res. Lett., 43, 701–708, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL066916, 2016.

Misstear, B., Vargas, C. R., Lapworth, D., Ouedraogo, I., and Podgorski, J.: A global perspective on assessing groundwater quality, Hydrogeol. J., 31, 11–14, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-022-02461-0, 2023.

Moeck, C., Collenteur, R. A., Berghuijs, W. R., Luijendijk, E., and Gurdak, J. J.: A Global Assessment of Groundwater Recharge Response to Infiltration Variability at Monthly to Decadal Timescales, Water Resources Research, 60, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023WR035828, 2024.

Müller Schmied, H., Adam, L., Eisner, S., Fink, G., Flörke, M., Kim, H., Oki, T., Portmann, F. T., Reinecke, R., Riedel, C., Song, Q., Zhang, J., and Döll, P.: Variations of global and continental water balance components as impacted by climate forcing uncertainty and human water use, Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 20, 2877–2898, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-20-2877-2016, 2016.

Müller Schmied, H., Cáceres, D., Eisner, S., Flörke, M., Herbert, C., Niemann, C., Peiris, T. A., Popat, E., Portmann, F. T., Reinecke, R., Schumacher, M., Shadkam, S., Telteu, C.-E., Trautmann, T., and Döll, P.: The global water resources and use model WaterGAP v2.2d: model description and evaluation, Geoscientific Model Development, 14, 1037–1079, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-14-1037-2021, 2021.

Naz, B. S., Sharples, W., Ma, Y., Goergen, K., and Kollet, S.: Continental-scale evaluation of a fully distributed coupled land surface and groundwater model, ParFlow-CLM (v3.6.0), over Europe, Geoscientific Model Development, 16, 1617–1639, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-16-1617-2023, 2023.

Nazari, S., Kruse, I. L., and Moosdorf, N.: Spatiotemporal dynamics of global rain-fed groundwater recharge from 2001 to 2020, Journal of Hydrology, 650, 132490, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.132490, 2025.

Niazi, H., Wild, T. B., Turner, S. W. D., Graham, N. T., Hejazi, M., Msangi, S., Kim, S., Lamontagne, J. R. and Zha, M.: Global peak water limit of future groundwater withdrawals, Nature Sustainability, 7, 413–422, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01306-w, 2024.

Niazi, H., Ferencz, S. B., Graham, N. T., Yoon, J., Wild, T. B., Hejazi, M., Watson, D. J., and Vernon, C. R.: Long-term hydro-economic analysis tool for evaluating global groundwater cost and supply: Superwell v1.1, Geoscientific Model Development, 18, 1737–1767, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-18-1737-2025, 2025.

Paneque Salgado, P. and Vargas Molina, J.: Drought, social agents and the construction of discourse in Andalusia, Environmental Hazards, 14, 224–235, https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2015.1058739, 2015.

Perez, N., Singh, V., Ringler, C., Xie, H., Zhu, T., Sutanudjaja, E. H., and Villholth, K. G.: Ending groundwater overdraft without affecting food security, Nature Sustainability, 7, 1007–1017, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01376-w, 2024.

Pokhrel, Y., Felfelani, F., Satoh, Y., Boulange, J., Burek, P., Gädeke, A., Gerten, D., Gosling, S. N., Grillakis, M., Gudmundsson, L., Hanasaki, N., Kim, H., Koutroulis, A., Liu, J., Papadimitriou, L., Schewe, J., Müller Schmied, H., Stacke, T., Telteu, C.-E., Thiery, W., Veldkamp, T., Zhao, F., and Wada, Y.: Global terrestrial water storage and drought severity under climate change, Nature Climate Change, 11, 226–233, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00972-w, 2021.

Porkka, M., Virkki, V., Wang-Erlandsson, L., Gerten, D., Gleeson, T., Mohan, C., Fetzer, I., Jaramillo, F., Staal, A., te Wierik, S., Tobian, A., van der Ent, R., Döll, P., Flörke, M., Gosling, S. N., Hanasaki, N., Satoh, Y., Müller Schmied, H., Wanders, N., Famiglietti, J. S., Rockström, J., and Kummu, M.: Notable shifts beyond pre-industrial streamflow and soil moisture conditions transgress the planetary boundary for freshwater change, Nature Water, 2, 262–273, https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-024-00208-7, 2024.

Portmann, F., Döll, P., Eisner, S., and Flörke, M.: Impact of climate change on renewable groundwater resources: Assessing the benefits of avoided greenhouse gas emissions using selected CMIP5 climate projections, Environmental Research Letters, 8, 024023, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024023, 2013.

Prusevich, A. A., Lammers, R. B., and Glidden, S. J.: Delineation of endorheic drainage basins in the MERIT-Plus dataset for 5 and 15 min upscaled river networks, Scientific Data, 11, 61, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02875-9, 2024.

Reinecke, R., Foglia, L., Mehl, S., Trautmann, T., Cáceres, D., and Döll, P.: Challenges in developing a global gradient-based groundwater model (G3M v1.0) for the integration into a global hydrological model, Geoscientific Model Development, 12, 2401–2418, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-2401-2019, 2019.

Reinecke, R., Müller Schmied, H., Trautmann, T., Andersen, L. S., Burek, P., Flörke, M., Gosling, S. N., Grillakis, M., Hanasaki, N., Koutroulis, A., Pokhrel, Y., Thiery, W., Wada, Y., Yusuke, S., and Döll, P.: Uncertainty of simulated groundwater recharge at different global warming levels: a global-scale multi-model ensemble study, Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 25, 787–810, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-787-2021, 2021.

Reinecke, R., Gnann, S., Stein, L., Bierkens, M., de Graaf, I., Gleeson, T., Essink, G. O., Sutanudjaja, E. H., Ruz Vargas, C., Verkaik, J., and Wagener, T.: Uncertainty in model estimates of global groundwater depth, Environmental Research Letters, 19, 114066, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ad8587, 2024.

Reinecke, R., Stein, L., Gnann, S., Andersson, J. C. M., Arheimer, B., Bierkens, M., Bonetti, S., Güntner, A., Kollet, S., Mishra, S., Moosdorf, N., Nazari, S., Pokhrel, Y., Prudhomme, C., Schewe, J., Shen, C., and Wagener, T.: Uncertainties as a Guide for Global Water Model Advancement, WIREs Water, 12, e70025, https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.70025, 2025a.

Reinecke, R., Bäthge, A., Dietrich, R., Gnann, S., Gosling, S., Grogan, D., Hartmann, A., Kollet, S., Kumar, R., Lammers, R., Liu, S., Liu, Y., Moosdorf, N., Naz, B., Nazari, S., Orazulike, C., Pokhrel, Y., Schewe, J., Smilovic, M., Strokal, M, Wada, Y., Zuidema, S., and de Graaf, I.: The ISIMIP Groundwater Sector: A Framework for Ensemble Modeling of Global Change Impacts on Groundwater, Zenodo [code and data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14962511, 2025b.

Rodell, M., Velicogna, I., and Famiglietti, J. S.: Satellite-based estimates of groundwater depletion in India, Nature, 460, 999–1002, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08238, 2009.

Rodella, A.-S., Zaveri, E., and Bertone, F.: The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Economics of Groundwater in Times of Climate Change, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/water/publication/the-hidden-wealth-of-nations-groundwater-in-times-of-climate (last access: 13 January 2026), 2023.

Rounce, D., Hock, R., and Maussion, F.: Global PyGEM-OGGM Glacier Projections with RCP and SSP Scenarios. (HMA2_GGP, Version 1). [Data Set], NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center [data set], https://doi.org/10.5067/P8BN9VO9N5C7, 2022.

Sarrazin, F., Hartmann, A., Pianosi, F., Rosolem, R., and Wagener, T.: V2Karst V1.1: a parsimonious large-scale integrated vegetation–recharge model to simulate the impact of climate and land cover change in karst regions, Geoscientific Model Development, 11, 4933–4964, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-4933-2018, 2018.

Scanlon, B. R., Fakhreddine, S., Rateb, A., de Graaf, I., Famiglietti, J., Gleeson, T., Grafton, R. Q., Jobbagy, E., Kebede, S., Kolusu, S. R., Konikow, L. F., Di Long, Mekonnen, M., Schmied, H. M., Mukherjee, A., MacDonald, A., Reedy, R. C., Shamsudduha, M., Simmons, C. T., Sun, A., Taylor, R. G., Villholth, K. G., Vörösmarty, C. J., and Zheng, C.: Global water resources and the role of groundwater in a resilient water future, Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 4, 87–101, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00378-6, 2023.

Schaller, M. F. and Fan, Y.: River basins as groundwater exporters and importers: Implications for water cycle and climate modeling, Journal of Geophysical Research, 114, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD010636, 2009.

Schwartz, F. W. and Ibaraki, M.: Groundwater: A Resource in Decline, Elements, 7, 175–179, https://doi.org/10.2113/gselements.7.3.175, 2011.

Smith, M. W., Willis, T., Mroz, E., James, W. H. M., Klaar, M. J., Gosling, S. N., and Thomas, C. J.: Future malaria environmental suitability in Africa is sensitive to hydrology, Science (New York, N. Y.), 384, 697–703, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adk8755, 2024.

Strokal, M., Kumar, R., Bak, M. P., Jones, E. R., Beusen, A. H. W., Flörke, M., Grizzetti, B., Nkwasa, A., Schweden, K., Ural-Janssen, A., van Griensven, A., Vigiak, O., van Vliet, M. T. H., Wang, M., de Graaf, I., Dürr, H. H., Gosling, S. N., Hofstra, N., Nakkazi, M. T., Ouedraogo, I., Reinecke, R., Strokal, V., Suresh, K., Tang, T., Teuling, F. S. R., Tilahun, A. B., Troost, T. A., van Wijk. D., and Micella, I.: Advancing water quality model intercomparisons under global change: perspectives from the new ISIMIP water quality sector, Environmental Research: Water, 1, 035002, https://doi.org/10.1088/3033-4942/adf571, 2025.

Taylor, R. G., Scanlon, B., Döll, P., Rodell, M., van Beek, R., Wada, Y., Longuevergne, L., Leblanc, M., Famiglietti, J. S., Edmunds, M., Konikow, L., Green, T. R., Chen, J., Taniguchi, M., Bierkens, M. F. P., MacDonald, A., Fan, Y., Maxwell, R. M., Yechieli, Y., Gurdak, J. J., Allen, D. M., Shamsudduha, M., Hiscock, K., Yeh, P. J.-F., Holman, I., and Treidel, H.: Ground water and climate change, Nature Climate Change, 3, 322–329, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1744, 2013.

Telteu, C.-E., Müller Schmied, H., Thiery, W., Leng, G., Burek, P., Liu, X., Boulange, J. E. S., Andersen, L. S., Grillakis, M., Gosling, S. N., Satoh, Y., Rakovec, O., Stacke, T., Chang, J., Wanders, N., Shah, H. L., Trautmann, T., Mao, G., Hanasaki, N., Koutroulis, A., Pokhrel, Y., Samaniego, L., Wada, Y., Mishra, V., Liu, J., Döll, P., Zhao, F., Gädeke, A., Rabin, S. S., and Herz, F.: Understanding each other's models: an introduction and a standard representation of 16 global water models to support intercomparison, improvement, and communication, Geoscientific Model Development, 14, 3843–3878, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-14-3843-2021, 2021.

Thompson, J. R., Gosling, S. N., Zaherpour, J., and Laizé, C. L. R.: Increasing Risk of Ecological Change to Major Rivers of the World With Global Warming, Earth's Future, 9, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EF002048, 2021.

Trullenque-Blanco, V., Beguería, S., Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Peña-Angulo, D., and González-Hidalgo, C.: Catalogue of drought events in peninsular Spanish along 1916–2020 period, Scientific Data, 11, 703, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03484-w, 2024.

United Nations: The United Nations World Water Development Report 2022: groundwater: making the invisible visible, UNESCO, Paris, ISBN 978-92-3-100507-7, 2022.

von Lampe, M., Willenbockel, D., Ahammad, H., Blanc, E., Cai, Y., Calvin, K., Fujimori, S., Hasegawa, T., Havlik, P., Heyhoe, E., Kyle, P., Lotze-Campen, H., Mason d'Croz, D., Nelson, G. C., Sands, R. D., Schmitz, C., Tabeau, A., Valin, H., van der Mensbrugghe, D., and van Meijl, H.: Why do global long-term scenarios for agriculture differ? An overview of the AgMIP Global Economic Model Intercomparison, Agricultural Economics, 45, 3–20, https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12086, 2014.

Wada, Y., van Beek, L. P. H., and Bierkens, M. F. P.: Nonsustainable groundwater sustaining irrigation: A global assessment, Water Resources Research, 48, W00L06, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011WR010562, 2012.

Winter, T. C.: The Role of Ground Water in Generating Streamflow in Headwater Areas and in Maintaining Base Flow 1, Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 43, 15–25, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.2007.00003.x, 2007.

Xie, J., Liu, X., Jasechko, S., Berghuijs, W. R., Wang, K., Liu, C., Reichstein, M., Jung, M., and Koirala, S.: Majority of global river flow sustained by groundwater, Nature Geoscience, 17, 770–777, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01483-5, 2024.

Yamazaki, D., Ikeshima, D., Sosa, J., Bates, P. D., Allen, G. H., and Pavelsky, T. M.: MERIT Hydro: A High-Resolution Global Hydrography Map Based on Latest Topography Dataset, Water Resources Research, 55, 5053–5073, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR024873, 2019.

Yang, Y., Donohue, R. J., and McVicar, T. R.: Global estimation of effective plant rooting depth: Implications for hydrological modeling, Water Resources Research, 52, 8260–8276, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016WR019392, 2016.

Zamrsky, D., Ruzzante, S., Compare, K., Kretschmer, D., Zipper, S., Befus, K. M., Reinecke, R., Pasner, Y., Gleeson, T., Jordan, K., Cuthbert, M., Castronova, A. M., Wagener, T., and Bierkens, M. F. P.: Current trends and biases in groundwater modelling using the community-driven groundwater model portal (GroMoPo), Hydrogeology Journal, 33, 355–366, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-025-02882-7, 2025.

Zipper, S., Befus, K. M., Reinecke, R., Zamrsky, D., Gleeson, T., Ruzzante, S., Jordan, K., Compare, K., Kretschmer, D., Cuthbert, M., Castronova, A. M., Wagener, T., and Bierkens, M. F. P.: GroMoPo: A Groundwater Model Portal for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) Modeling, Ground Water, https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.13343, 2023.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The ISIMIP framework

- The current generation of groundwater models in the sector

- Unstructured experiments point out model differences that should be explored further

- Groundwater as a linking sector in ISIMIP

- A vision for the ISIMIP groundwater sector

- Appendix A

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The ISIMIP framework

- The current generation of groundwater models in the sector

- Unstructured experiments point out model differences that should be explored further

- Groundwater as a linking sector in ISIMIP

- A vision for the ISIMIP groundwater sector

- Appendix A

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References