the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The Met Office Unified Model Global Atmosphere 8.0 and JULES Global Land 9.0 configurations

Martin Willett

Melissa Brooks

Andrew Bushell

Paul Earnshaw

Samantha Smith

Lorenzo Tomassini

Martin Best

Ian Boutle

Jennifer Brooke

John M. Edwards

Andrew D. Elvidge

Kalli Furtado

Catherine Hardacre

Andrew J. Hartley

Alan J. Hewitt

Ben Johnson

Adrian Lock

Andy Malcolm

Jane Mulcahy

Eike Müller

Ian A. Renfrew

Heather Rumbold

Gabriel G. Rooney

Alistair Sellar

Masashi Ujiie

Annelize van Niekerk

Andy Wiltshire

Michael Whitall

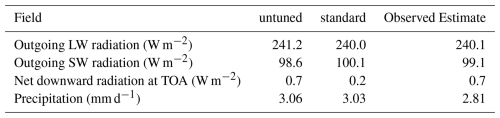

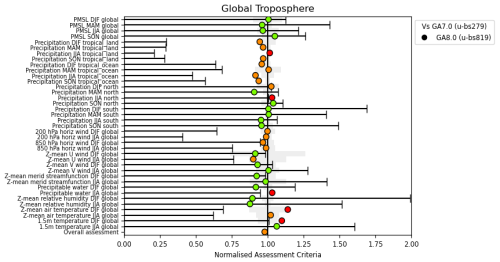

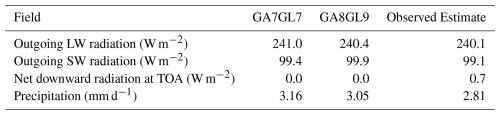

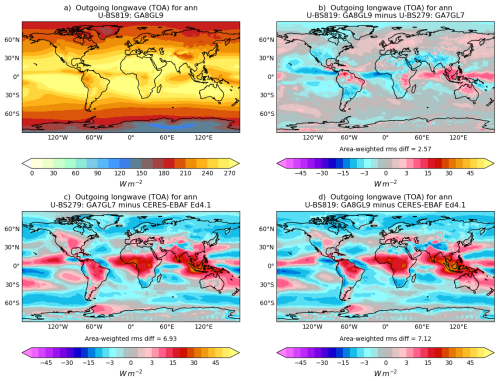

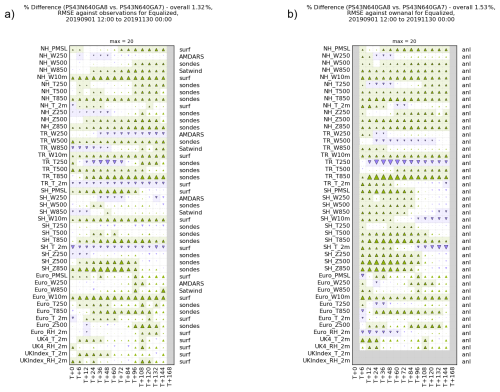

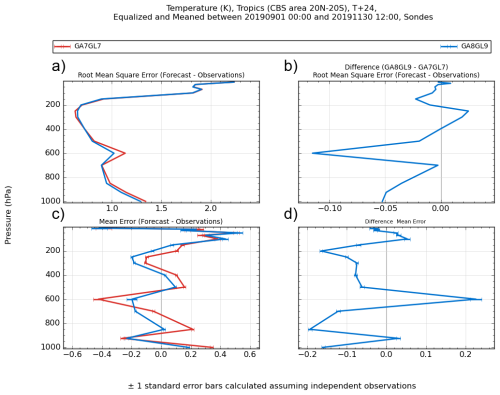

We describe Global Atmosphere 8.0 and Global Land 9.0 (GA8GL9) that are science configurations of the Met Office Unified Model and Joint UK Land Environment Simulator (JULES) land surface model developed for use across weather and climate timescales. GA8GL9 builds upon GA7GL7. It not only consolidates the changes made for the climate branch configuration GA7.1GL7.1 (the atmosphere and land components of the physical model used in HadGEM3-GC3.1, UKESM1 and UKESM1.1 which were all used in the Met Office's CMIP6 submissions) and NWP branch configuration GA7.2GL8.1 (the operational global NWP model at the Met Office between 2019 and 2022), but also includes developments to most areas of the science. Some of the key changes include: prognostic-based entrainment, which adds convective memory and improves precipitation rates and spatial structures; time-smoothed convective increments, which improves the convection-dynamics coupling and greatly reduces the detrimental dynamical effects of convective intermittency; a new riming parametrisation, which increases the amount of supercooled water and hence reduces Southern Ocean biases; and a package of land surface changes, which improves the forecast of near-surface fields and hence removes the need for the aggregate surface tile in NWP applications. Several changes are made that reduce numerical artefacts and improve the numerical stability of the model. The NWP and climate performance of GA8GL9 is evaluated against the previous configuration, GA7GL7. In NWP tests GA8GL9 is shown have reduced errors and improved spatial structure. The mean climate in GA8GL9 is shown to be improved relative to GA7GL7 with notable improvements in the top of atmosphere outgoing shortwave radiation. GA8GL9 is the atmosphere and land component of GC4, and GC4 has been used as the operational global NWP model at the Met Office since May 2022.

- Article

(6772 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The works published in this journal are distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This license does not affect the Crown copyright work, which is re-usable under the Open Government Licence (OGL). The Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License and the OGL are interoperable and do not conflict with, reduce or limit each other.

© Crown copyright 2026

At the Met Office and other UM partners the Unified Model (UM) and the Joint UK Land Environment Simulator (JULES) are used in defined Global Atmosphere (GA) and Global Land1 (GL) configurations to simulate the global atmosphere-land system. The GA/GL development process is described in Walters et al. (2011). Each subsequent GA configuration is built upon the previous configuration. For example, the subject of this report, GA8GL9, is built upon the previous configuration GA7.0GL7.0 (Walters et al., 2019). Each GA/GL configuration is designed for use across all timescales and global resolutions and hence is assessed in terms of both its climate and Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) performance. Global coupled (GC) configurations also include Global Ocean (GO) and Global Sea-Ice (GSI) components to simulate the global atmosphere-land-ocean-sea-ice system.

Branch configurations may be developed from the GC/GA/GL trunks for use in specific applications. These will usually include a small number of tunings and science developments pulled forward from the next development cycle. GA7.0 spawned two branch configurations: GA7.1 (Walters et al., 2019), which was intended for climate applications, and GA7.2 (Willett et al., 2023), which was intended for NWP applications. Note that GA7.2 is developed from GA7.0 and not from GA7.1. GA7.1 is the atmospheric component of the physical model used in HadGEM3-GC3.1 (Williams et al., 2017), UKESM1 (Sellar et al., 2019) and UKESM1.1 (Mulcahy et al., 2023), which were all used in the Met Office's CMIP6 submissions. GA7.2 was the operational global NWP atmosphere model between December 2019 and May 2022. GA8 reintegrates the changes made for both GA7.1 and GA7.2 back onto the GA trunk. For brevity in this document the suffix “.0” will be dropped when referring to the trunk configurations (GA7.0, GL7.0, GA8.0, GL8.0, GL9.0).

The land component described in this paper is GL9 rather than GL8 because an intermediate land configuration, GL8 (Willett et al., 2023), was defined in 2018. GL8 includes improvements to sea-ice drag and the representation of snow grains. GL8.1 is the aggregate surface tile version of GL8 whereby the surface fluxes are calculated using a single tile with the aggregated properties of the nine individual surface types rather than by aggregating the fluxes from the nine individual tiles (Walters et al., 2017). GL8.1 was the operational global NWP land surface model between September 2018 and June 2022; initially it was used in combination with GA6.1 and from December 2019 it was used in combination with GA7.2. All the developments included between GL7 and GL8 are included in GL9 and are described in this paper.

GC4 couples GA8GL9 with the GO6 ocean (Storkey et al., 2018) and the GSI8.1 sea ice (Ridley et al., 2018). GA8GL9 and GC4 were released in early 2021. GC4 has been used for operational global NWP at the Met Office since May 2022, but there are no plans to use it for operational climate applications. GA8GL9/GC4 is used as a baseline for future model developments (e.g. Lock et al., 2024) and for other research activities. The next GA and GL configuration, GAL9, will build upon GA8GL9.

The primary aims of this paper are to provide a standalone scientific description of GA8GL9 (and hence a single reference) and to describe how GA8GL9 differs from the previous configuration, GA7GL7. To that end, Sect. 2 of this document provides a scientific description of GA8GL92, and Sect. 3 details all changes made between GA7GL7 and GA8GL9. The development of these changes is documented using “trac” issue tracking software; for consistency with that documentation, we have included the trac ticket numbers with each change. A full assessment of the performance of GA8GL9/GC4 relative to appropriate controls is made in Xavier et al. (2024), but a brief assessment of GA8GL9 relative to GA7GL7 is given in Sect. 4.

2.1 Dynamical formulation and discretisation

The UM's ENDGame dynamical core uses a semi-implicit semi-Lagrangian formulation to solve the non-hydrostatic, fully-compressible deep-atmosphere equations of motion (Wood et al., 2014). The primary atmospheric prognostics are the three-dimensional wind components, virtual dry potential temperature, Exner pressure, and dry density, whilst moist prognostics such as the mass mixing ratio of water vapour and prognostic cloud fields as well as other atmospheric loadings are advected as free tracers. These prognostic fields are discretised horizontally onto a regular longitude/latitude grid with Arakawa C-grid staggering (Arakawa and Lamb, 1977), whilst the vertical discretisation utilises a Charney-Phillips staggering (Charney and Phillips, 1953) using terrain-following hybrid height coordinates. The discretised equations are solved using a nested iterative approach centred about solving a linear Helmholtz equation. By convention, global configurations are defined on 2×N longitudes and 1.5×N latitudes of scalar grid-points, with the meridional wind variable first stored at the north and south poles, and scalar and zonal wind variables first stored half a grid length away from the poles. This choice makes the grid-spacing approximately isotropic in the mid-latitudes and means that the integer N, which represents the maximum number of zonal 2 grid-point waves that can be represented by the model, uniquely defines its horizontal resolution; a model with N=96 is said to be N96 resolution. Limited-area configurations use a rotated longitude/latitude grid with the pole rotated so that the grid's equator runs through the centre of the model domain. In the vertical, most climate configurations use an 85-level set labelled L85(50t,35s)85, which has 50 levels below 18 km (and hence at least sometimes in the troposphere), 35 levels above this (and hence solely in or above the stratosphere) and a fixed model lid 85 km above sea level. Finally, numerical weather prediction (NWP) configurations use a 70-level set, L70(50t,20s)80 which has an almost identical 50 levels below 18 km, a model lid at 80 km, but has a reduced stratospheric resolution compared to L85(50t,35s)85. Although we use a range of vertical resolutions in the stratosphere, a consistent tropospheric vertical resolution is currently used for a given GA configuration. A more detailed description of these level sets is included in the Supplement to Walters et al. (2019).

2.2 Structure of the atmospheric model time step

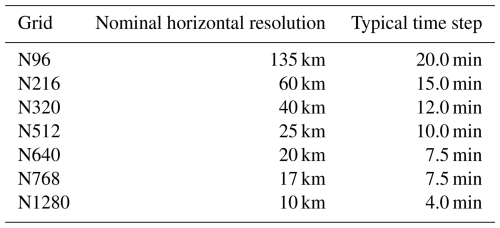

With ENDGame, the UM uses a nested iterative structure for each atmospheric time step within which processes are split into an outer loop and an inner loop. The semi-Lagrangian departure point equations are solved within the outer loop using the latest estimates for the wind variables. Appropriate fields are then interpolated to the updated departure points. Within the inner loop, the Coriolis, orographic and non-linear terms are solved along with a linear Helmholtz problem to obtain the pressure increment. The Helmholtz problem is solved using a multigrid method as described in Sect. 3.7.1. Latest estimates for all variables are then obtained from the pressure increment via a back-substitution process; see Wood et al. (2014) for details. The physical parametrisations are split into slow processes (radiation, large-scale precipitation and gravity wave drag) and fast processes (atmospheric boundary layer turbulence, convection and surface coupling). The slow processes are treated in parallel and are computed once per time step before the outer loop. The source terms from the slow processes are then added on to the appropriate fields before interpolation. The fast processes are treated sequentially and are computed in the outer loop using the latest predicted estimate for the required variables at the next, n+1 time step. A summary of the atmospheric time step is given in Algorithm 1. In practice two iterations are used for each of the outer and inner loops so that the Helmholtz problem is solved four times per time step. The prognostic aerosol scheme is included via a call to the UK Chemistry and Aerosol (UKCA) code after the main atmospheric time step; this call is currently performed once per hour. Finally, Table 1 contains the typical length of time step used for a range of horizontal resolutions.

Algorithm 1Iterative structure of time step n+1. Here, we use two inner and two outer loops (L=2, M=2).

2.3 Solar and terrestrial radiation

Shortwave (SW) radiation from the Sun is absorbed and reflected in the atmosphere and at the Earth's surface and provides energy to drive the atmospheric circulation. Longwave (LW) radiation is emitted from the planet and interacts with the atmosphere, redistributing heat, before being emitted into space. These processes are parametrised via the radiation scheme, which provides prognostic atmospheric temperature increments, prognostic surface fluxes and additional diagnostic fluxes. The SOCRATES (https://code.metoffice.gov.uk/trac/socrates, last access: 2 February 2026) radiative transfer scheme (Edwards and Slingo, 1996; Manners et al., 2015) is used for GA8. Solar radiation is treated in 6 SW bands and thermal radiation in 9 LW bands, as outlined in Table 2. Gaseous absorption uses the correlated-k method with newly derived coefficients for all gases (except where indicated below) based on the HITRAN 2012 spectroscopic database (Rothman et al., 2013). Scaling of absorption coefficients uses a look-up table of 59 pressures with 5 temperatures per pressure level based around a mid-latitude summer profile. The method of equivalent extinction (Edwards, 1996; Amundsen et al., 2017) is used for minor gases in each band. The water vapour continuum is represented using laboratory results from the CAVIAR project (Continuum Absorption at Visible and Infrared wavelengths and its Atmospheric Relevance) between 1 and 5 µm (Ptashnik et al., 2011, 2012) and version 2.5 of the Mlawer–Tobin_Clough–Kneizys–Davies (MT_CKD-2.5) model (Mlawer et al., 2012) at other wavelengths.

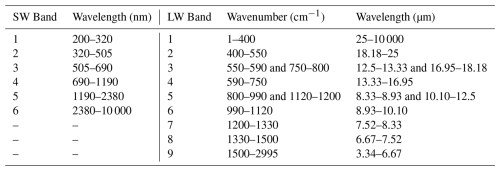

Table 2Spectral bands for the treatment of incoming solar (SW) radiation (left) and thermal (LW) radiation (right).

Forty-one (41) k terms are used for the major gases in the SW bands. Absorption by water vapour (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), ozone (O3), oxygen (O2), nitrous oxide (N2O) and methane (CH4) is included. Ozone cross-sections for the ultra-violet and visible come from Serdyuchenko et al. (2014) and Gorshelev et al. (2014), along with Brion-Daumont-Malicet (Daumont et al., 1992; Malicet et al., 1995) for the far-UV. In the first SW band, a single k-term is calculated for each 20 nm sub-interval from 200 to 320 nm, and in band 2, a single k-term is calculated for each of the sub-intervals 320–400 and 400–505 nm. This allows the incoming solar flux to be supplied on these finer wavelength bands for experiments concerning solar spectral variability. The solar spectrum uses data from NRLSSI (Lean et al., 2005) as recommended by the SPARC/SOLARIS (http://solarisheppa.geomar.de/ccmi, last access: 2 February 2026) group. A mean solar spectrum for the period 2000–2011 is used when a varying spectrum is not invoked.

Eighty-one (81) k terms are used for the major gases in the LW bands. Absorption by H2O, O3, CO2, CH4, N2O, CFC-11 (CCl3F), CFC-12 (CCl2F2) and HFC134a (CH2FCF3) is included. For climate simulations, the atmospheric concentrations of CFC-12 and HFC134a are adjusted to represent absorption by all the remaining trace halocarbons. The treatment of CO2 absorption for the peak of the 15 µm band (LW band 4) is as described in Zhong and Haigh (2000). An improved representation of CO2 absorption in the “window” region (8–13 µm) provides a better forcing response to increases in CO2 (Pincus et al., 2015). The method of “hybrid” scattering is used in the LW which runs full scattering calculations for 27 of the major gas k-terms (where their nominal optical depth is less than 10 in a mid-latitude summer atmosphere). For the remaining 54 k-terms (optical depth > 10) much cheaper non-scattering calculations are run.

Of the major gases considered, only H2O is prognostic; O3 uses a zonally symmetric climatology, whilst other gases are prescribed using either fixed or time-varying mass mixing ratios and assumed to be well mixed.

Absorption and scattering by the following prognostic aerosol species (the representation of which is discussed in Sect. 2.10 below) are included in both the SW and LW using the UKCA-Radaer scheme: sulphate, black carbon, organic carbon and sea salt. The aerosol scattering and absorption coefficients and asymmetry parameters are precomputed for a wide range of plausible Mie parameters and stored in look-up tables for use during run-time when the atmospheric chemical composition, including mean aerosol particle radius and water content are known. As the aerosol species are internally mixed within the modal aerosol scheme (see Table 4 in Walters et al., 2019) the refractive indices of each mode are calculated online as a volume weighted mean of the component species contributing to that mode. The component refractive indices are documented in the Appendix of Bellouin et al. (2013). Nucleation mode particles are neglected as they are not expected to contribute significantly to the atmospheric optical properties. The parametrisation of cloud droplets is described in Edwards and Slingo (1996) using the method of “thick averaging”. Padé fits are used for the variation with effective radius, which is computed from the number of cloud droplets. In configurations using prognostic aerosol, cloud droplet number concentrations are not calculated within the radiation scheme itself but are calculated by the UKCA-Activate scheme (West et al., 2014), which is based on the activation scheme of Abdul-Razzak and Ghan (2000). In NWP configurations, cloud droplet number concentration is not calculated within the radiation scheme but instead is calculated via the method described in Jones et al. (1994); this is done to reduce computational cost. Note that in simulations using climatological rather than prognostic aerosol, the approach described here is not yet available and instead we use CLASSIC (Coupled Large-scale Aerosol Simulator for Studies in Climate, Bellouin et al., 2011) aerosol climatologies and the calculation of optical properties and cloud droplet concentrations described in Sect. 2.3 of Walters et al. (2017). Both prognostic and climatological simulations of mineral dust use the CLASSIC scheme. The parametrisation of ice crystals is described in Baran et al. (2016). Full treatment of scattering is used in both the SW and LW. The sub-grid cloud structure is represented using the Monte Carlo Independent Column Approximation (McICA) (Pincus et al., 2003 with enhancements and implementation described in Hill et al., 2011), with the parametrisation of subgrid-scale water content variability described in Hill et al. (2015).

Full radiation calculations are made every hour using the instantaneous cloud fields and a mean solar zenith angle for the following 1 h period. Corrections are made for the change in solar zenith angle on every model time step as described in Manners et al. (2009). The emissivity and the albedo of the surface are set by the land surface model. The direct SW flux at the surface is corrected for the angle and aspect of the topographic slope as described in Manners et al. (2012).

2.4 Large-scale precipitation

The formation and evolution of precipitation due to grid scale processes is the responsibility of the large-scale precipitation – or microphysics – scheme, whilst small-scale precipitating events are handled by the convection scheme. The microphysics scheme has prognostic input fields of temperature, moisture, cloud and precipitation from the end of the previous time step, which it modifies in turn. The microphysics used is a single moment scheme based on Wilson and Ballard (1999), with extensive modifications. The warm-rain scheme is based on Boutle et al. (2014b), and includes a prognostic rain formulation, which allows three-dimensional advection of the precipitation mass mixing ratio, and an explicit representation of the effect of sub-grid variability on autoconversion and accretion rates (Boutle et al., 2014a). We use the rain-rate dependent particle size distribution of Abel and Boutle (2012) and fall velocities of Abel and Shipway (2007), which combine to allow a better representation of the sedimentation and evaporation of small droplets. We also make use of multiple sub-time steps of the precipitation scheme, with one call to the scheme for every two minutes of model time step. This is required to achieve a realistic treatment of in-column evaporation. With prognostic aerosol, we use the UKCA-Activate aerosol activation scheme (West et al., 2014) to provide the cloud droplet number for autoconversion, where particles from the soluble aerosol modes are activated into cloud droplets. The soluble modes comprise sulphate, sea salt, black carbon and organic carbon but with black carbon remaining hydrophobic within the internally mixed particles. The Aitken insoluble mode comprised of black carbon and organic carbon also participates in activation to form cloud condensation nuclei. When using climatological aerosol, the cloud droplet number is the same as that used in the radiation scheme. Ice cloud parametrisations use the generic size distribution of Field et al. (2007) and mass-diameter relations of Cotton et al. (2013).

2.5 Large-scale cloud

Cloud appears on sub-grid scales well before the humidity averaged over the size of a model grid box reaches saturation. A cloud parametrisation scheme is therefore required to determine the fraction of the grid box which is covered by cloud, and the amount and phase of condensed water contained in this cloud. The formation of cloud will convert water vapour into liquid or ice and release latent heat. The cloud cover and liquid and ice water contents are then used by the radiation scheme to calculate the radiative impact of the cloud and by the large-scale precipitation scheme to calculate whether any precipitation has formed.

The parametrisation used is the prognostic cloud fraction and prognostic condensate (PC2) scheme (Wilson et al., 2008a, b) along with the cloud erosion parametrisation described by Morcrette (2012) and critical relative humidity parametrisation described in Van Weverberg et al. (2016). PC2 uses three prognostic variables for water mixing ratio – vapour, liquid and ice – and a further three prognostic variables for cloud fraction: liquid, ice and mixed-phase. The following atmospheric processes can modify the cloud fields: SW radiation, LW radiation, boundary layer processes, convection, precipitation, small-scale mixing (cloud erosion), advection and changes in atmospheric pressure. The convection scheme calculates increments to the prognostic liquid and ice water contents by detraining condensate from the convective plume, whilst the cloud fractions are updated using the non-uniform forcing method of Bushell et al. (2003). One advantage of the prognostic approach is that cloud can be transported away from where it was created. For example, anvils detrained from convection can persist and be advected downstream long after the convection itself has ceased. The radiative impact of convective cores, which hold condensate not detrained into the environment, is represented by diagnosing a convective cloud amount (CCA) and convective cloud water (CCW) where the convection is active on a particular time-step. The CCA and CCW then get combined with the PC2 cloud fraction and condensate variables before these get passed to McICA to calculate the radiative impact of the combined cloud fields. Finally, the production of supercooled liquid water in a turbulent environment is parametrised following Furtado et al. (2016).

2.6 Sub-grid orographic drag

The effect of local and mesoscale orographic features not resolved by the mean orography, from individual hills through to small mountain ranges, must be parametrised. The smallest scales, where buoyancy effects are assumed to be unimportant, are represented by the explicit orographic stress parametrisation of Wood et al. (2001). The effects of the remainder of the sub-grid orography (on scales where buoyancy effects are important) are parametrised by a drag scheme which represents the effects of low-level flow blocking and the drag associated with stationary gravity waves (mountain waves). This is based on the scheme described by Lott and Miller (1997), but with some important differences, described in more detail in Vosper (2015).

The sub-grid orography is assumed to consist of uniformly distributed elliptical mountains within the grid box, described in terms of a height amplitude, which is proportional to the grid box standard deviation of the source orography data, anisotropy (the extent to which the sub-grid orography is ridge-like, as opposed to circular), the alignment of the major axis and the mean slope along the major axis. The scheme is based on two different frameworks for the drag mechanisms: bluff body dynamics for the flow-blocking and linear gravity waves for the mountain wave drag component.

The degree to which the flow is blocked and so passes around, rather than over the mountains is determined by the Froude number, where H is the assumed sub-grid mountain height (proportional to the sub-grid standard deviation of the source orography data) and N and U are respectively measures of the buoyancy frequency and wind speed of the low-level flow. When F is less than the critical value, Fc, a fraction of the flow is assumed to pass around the sides of the orography, and a drag is applied to the flow within this blocked layer. Mountain waves are generated by the remaining proportion of the layer, which the orography pierces through. The acceleration of the flow due to wave stress divergence is exerted at levels where wave breaking is diagnosed. The kinetic energy dissipated through the flow-blocking drag, the mountain-wave drag and the non-orographic gravity wave drag (see Sect. 2.7 below) is returned to the atmosphere as a local heating term.

2.7 Non-orographic gravity wave drag

Non-orographic sources – such as convection, fronts and jets – can force gravity waves with non-zero phase speed. These waves break in the upper stratosphere and mesosphere, depositing momentum, which contributes to driving the zonal mean wind and temperature structures away from radiative equilibrium. Waves on scales too small for the model to sustain explicitly are represented by a spectral sub-grid parametrisation scheme (Scaife et al., 2002), which by contributing to the deposited momentum leads to a more realistic tropical quasi-biennial oscillation (QBO). The scheme, described in more detail in Walters et al. (2011), represents processes of wave generation, conservative propagation and dissipation by critical-level filtering and wave saturation acting on a vertical wavenumber spectrum of gravity wave fluxes following Warner and McIntyre (2001). Momentum conservation is enforced at launch in the lower troposphere, where isotropic fluxes guarantee zero net momentum, and by imposing a condition of zero vertical wave flux at the model's upper boundary. In between, momentum deposition occurs in each layer where reduced integrated flux results from erosion of the launch spectrum, after transformation by conservative propagation, to match the locally evaluated saturation spectrum.

2.8 Atmospheric boundary layer

Turbulent motions in the atmosphere are not resolved by global atmospheric models, but are important to parametrise in order to give realistic vertical structure in the thermodynamic and wind profiles. Although referred to as the “boundary layer” (BL) scheme, this parametrisation represents mixing over the full depth of the troposphere. The scheme is that of Lock et al. (2000) with the modifications described in Lock (2001) and Brown et al. (2008). It is a first-order turbulence closure mixing adiabatically conserved heat and moisture variables, momentum and tracers. For unstable BLs, diffusion coefficients (K profiles) are specified functions of height within the BL, related to the strength of the turbulence forcing. Two separate K profiles are used, one for surface sources of turbulence (surface heating and wind shear) and one for cloud top sources (radiative and evaporative cooling). The existence and depth of unstable layers is diagnosed initially by two moist adiabatic parcels, one released from the surface, the other from cloud-top. The top of the K profile for surface sources and the base of that for cloud-top sources are then adjusted to ensure that, from the resultant buoyancy flux, the magnitude of the buoyancy consumption of turbulence kinetic energy is limited to a specified fraction of buoyancy production, integrated across the BL. This can permit the cloud layer to decouple from the surface (Nicholls, 1984). This same energetic diagnosis is used to limit the vertical extent of the surface-driven K profile when cumulus convection is diagnosed (through comparison of cloud and sub-cloud layer moisture gradients), except that in this case no condensation is included in the diagnosed buoyancy flux because that part of the distribution is handled by the convection scheme (which is triggered at cloud base). Mixing across the top of the BL is through an explicit entrainment parametrisation that can either be resolved across a diagnosed inversion thickness or, if too thin, is coupled to the radiative fluxes and the dynamics through a sub-grid inversion diagnosis. If the thermodynamic conditions are right, cumulus penetration into a stratocumulus layer can generate additional turbulence and cloud-top entrainment in the stratocumulus by enhancing evaporative cooling at cloud top. In convective BLs, the scheme includes additional non-local fluxes of heat and momentum that represent the efficient mixing by convective thermals. These generate the vertically uniform potential temperature and wind profiles seen in observations. Primarily for stable BLs and in the free troposphere, diffusion coefficients are also calculated using a local Richardson number scheme based on Smith (1990), with the final coefficients being the maximum of this and the non-local ones described above. The stability dependence in unstable BLs uses the “conventional function” of Brown (1999) that gives only weak enhancement over neutral mixing, as we expect the non-local scheme to be most appropriate in this regime. The stability dependence in stable BLs is given by the “sharp” function over sea and by the “MES-tail” function over land (which matches linearly between an enhanced mixing function at the surface and “sharp” at 200 m and above), as defined in Brown et al. (2008). This additional near-surface mixing is motivated by the effects of surface heterogeneity, such as those described in McCabe and Brown (2007). The resulting diffusion equation is solved implicitly using the monotonically damping, second-order-accurate, unconditionally stable numerical scheme of Wood et al. (2007). The kinetic energy dissipated through the turbulent shear stresses is returned to the atmosphere as a local heating term.

2.9 Convection

The convection scheme represents the sub-grid scale transport of heat, moisture and momentum associated with cumulus cloud within a grid box. The UM uses a mass flux convection scheme based on Gregory and Rowntree (1990) with various extensions to include down-draughts (Gregory and Allen, 1991) and convective momentum transport (CMT). The current scheme consists of three stages: (i) convective diagnosis to determine whether convection is possible from the BL; (ii) a call to the shallow or deep convection scheme for all points diagnosed deep or shallow by the first step; and (iii) a call to the mid-level convection scheme for all grid points.

The diagnosis of shallow and deep convection is based on an undilute parcel ascent from the near surface for grid boxes where the surface buoyancy flux is positive and forms part of the BL diagnosis (Lock et al., 2000). Shallow convection is then diagnosed if the following conditions are met: (i) the parcel attains neutral buoyancy below 2.5 km or below the freezing level, whichever is higher, and (ii) the air in model levels forming a layer of order 1500 m above this has a mean upward vertical velocity less than 0.02 m s−1. Otherwise, convection diagnosed from the BL is defined as deep.

The deep convection scheme differs from the original Gregory and Rowntree (1990) scheme in using a convective available potential energy (CAPE) closure based on Fritsch and Chappell (1980). Mixing detrainment rates now depend on relative humidity and forced detrainment rates adapt to the buoyancy of the convective plume (Derbyshire et al., 2011). The entrainment is dependent on the level of recent convective activity as described in Willett and Whitall (2017) and summarised in Sect. 3.5.3. A numerically a more stable version of the Gregory et al. (1997) CMT scheme is used which is described in Sect. 3.5.2.

The shallow convection scheme uses a closure based on Grant (2001) and has relatively large entrainment rates consistent with cloud-resolving model (CRM) simulations of shallow convection. The shallow CMT uses flux–gradient relationships derived from CRM simulations of shallow convection (Grant and Brown, 1999).

The mid-level scheme operates on any instabilities found in a column above the top of deep or shallow convection or above the lifting condensation level. The scheme is largely unchanged from Gregory and Rowntree (1990) but uses the numerically more stable version of the Gregory et al. (1997) CMT scheme and a CAPE closure. The mid-level scheme typically operates overnight over land when convection from the stable BL is no longer possible or in the region of strong dynamical forcing such as tropical cylcones or mid-latitude storms. Other cases of mid-level convection tend to remove instabilities over a few levels and do not produce much precipitation.

Condensed water in the updraught parcel is converted to precipitation when it exceeds a critical value. This critical value is simply parametrised as a fixed fraction of the local environmental saturated specific humidity () bounded by fixed upper (1 g kg−1) and lower limits (0.4 g kg−1) (see Walters et al., 2014, Eq. 7). The convective precipitation may either evaporate within the downdraught, evaporate in the environment below cloud base, or reach the surface. Detrained convective condensate is converted directly to large-scale cloud condensate and the large-scale cloud fraction is updated using the “injection forcing” method described in Wilson et al. (2008a).

The timescale for the CAPE closure, which is used for deep and mid-level convection schemes, varies according to the large-scale vertical velocity. The values used vary from a minimum value of 30 min when the ascent is relatively strong, to a maximum of either 4 h for mid-level convection, or the minimum of either 4 h or a time scale from a surface flux closure for deep convection.

The convection scheme is sub-stepped with two sequential calls to the shallow, mid-level and deep convection schemes per model timestep, with each call using half the full model timestep. This was originally introduced to improve the numerical stability of the model.

To mitigate against the detrimental dynamical effects of intermittency within the convection scheme, the potential temperature and humidity increments from the convection scheme as seen by the rest of the model are damped in time with a damping timescale of 45 min.

2.10 Atmospheric aerosols

As discussed in Walters et al. (2011), the precise details of the modelling of atmospheric aerosols and chemistry is considered as a separate component of the full Earth system and remains outside the scope of this document. The aerosol species represented and their interaction with the atmospheric parametrisations is, however, part of the Global Atmosphere component and is therefore included. GA8 provides the option to use either prognostic aerosols or climatological aerosols with the choice being dependent on the needs of the application.

If prognostic aerosols are used this is done using the GLOMAP-mode (Global Model of Aerosol Processes) aerosol scheme described in Mann et al. (2010) with updates described in Mulcahy et al. (2018). The scheme simulates speciated aerosol mass and number in 4 soluble modes covering the sub-micron to super-micron aerosol size ranges (nucleation, Aitken, accumulation and coarse modes) as well as an insoluble Aitken mode. The prognostic aerosol species represented are sulphate, black carbon, organic carbon and sea salt. For more details see Walters et al. (2019) and Mulcahy et al. (2020).

If climatological aerosols are used this is done so using three-dimensional monthly climatologies for each aerosol species to model both the direct and indirect aerosol effects. In GA8, we continue to use the use climatologies based on the CLASSIC aerosol scheme (Bellouin et al., 2011) as described in Walters et al. (2017), which has a different representation of aerosol species and their direct and indirect aerosol effects compared to GLOMAP-mode. Future GA releases aim to use aerosol climatologies based on GLOMAP and will provide greater consistency between prognostic and climatological representations of the aerosol.

In addition to the treatment of these tropospheric aerosols, we include simple representations of the radiative impact of stratospheric aerosols, such as those related to injections of SO2 from explosive volcanic eruptions, because the GLOMAP-mode and CLASSIC climatologies do not sufficiently capture sources of stratospheric aerosols. In NWP simulations this is prescribed using a coarse-grain stratospheric aerosol climatology based on Cusack et al. (1998), while in climate simulations we apply the CMIP6 forcing of Thomason et al. (2018) as described in Sect. 3.2.1 of Sellar et al. (2020). Mineral dust is simulated using the CLASSIC dust scheme described in Woodward (2011). We also include the production of stratospheric water vapour via a simple methane oxidation parametrisation (Untch and Simmons, 1999).

2.11 Surface flux exchange, land surface and hydrology: Global Land 9.0

The exchange of fluxes between the surface (land, sea and sea-ice) and the atmosphere is an important mechanism for heating and moistening the atmospheric BL. In addition, the exchange of CO2 and other greenhouse gases plays a significant role in the climate system. The hydrological state of the land surface contributes to impacts such as flooding and drought as well as providing freshwater fluxes to the ocean, which influences ocean circulation. The Global Land configuration uses a community land surface model, JULES (Best et al., 2011; Clark et al., 2011), to model all of these processes in atmosphere/land only and in coupled applications.

In atmosphere/land only applications, the sea surface temperature (SST) is prescribed via an ancillary file. The sea-ice is simply modelled within JULES as a single layer of ice with fixed thickness and areal heat capacity, with the top boundary condition given by the heat flux into the sea-ice and a bottom boundary set to the freezing temperature of sea water. The surface temperature is determined from the surface energy balance using the gradient between the surface and ice temperatures, with a fixed thermal conductivity. Although the details of coupling between the atmosphere, ocean and sea-ice models when running in coupled simulations lie outside the scope of this paper, it is useful to note, however, where the boundaries lie between JULES, and the ocean and sea-ice components when GA8GL9 is run in coupled mode as part of GC4. In GC4, the SST is set to be equal to the temperature of the 1 m-thick, top ocean layer, which is calculated within the ocean model, with JULES being used to calculate the surface fluxes that are subsequently passed back to the ocean. Over the sea-ice, JULES is used to calculate both the skin temperature of the top sea-ice layer and the surface fluxes, because this has been shown to be both more accurate and more numerically stable than calculating them within the sea-ice model (West et al., 2016).

A tile approach is used to represent sub-grid scale heterogeneity of the land-surface (Essery et al., 2003b), with the surface of each land grid box subdivided into five types of vegetation (broadleaf trees, needle-leaved trees, temperate C3 grass, tropical C4 grass and shrubs) and four non-vegetated surface types (urban areas, inland water, bare soil and land ice). The ground beneath vegetation is coupled to the vegetation canopy by LW radiation and turbulent sensible heat exchanges. JULES also uses a canopy radiation scheme to represent the penetration of light within the vegetation canopy and its subsequent impact on photosynthesis (Mercado et al., 2007). The canopy also interacts with falling snow. Snow buries the canopy for most vegetation types, but the interception of snow by both needle-leaved and broad-leaved trees is represented with separate snow stores on the canopy and on the ground. This impacts the surface albedo, the snow sublimation and the snow melt (Essery et al., 2003a). The vegetation canopy code has been adapted for use with the urban surface type by defining an “urban canopy” with the thermal properties of concrete (Best, 2005), and evaluates well for the surface heat and moisture fluxes (Grimmond et al., 2011; Lipson et al., 2023).

Following Best et al. (2011), this canopy approach has also been adopted for the representation of inland water3. By defining an “inland water canopy” and setting the thermal characteristics to those of a suitable mixed layer depth of water (≈5 m), a better diurnal and seasonal cycle for the surface temperature is achieved than for the original “permanently saturated soil” approach (Rooney and Jones, 2010). The depth of the water in the canopy is held fixed, but global water conservation is pragmatically ensured by a small global adjustment to the water content of the deepest soil level (with appropriate checks to avoid negative values or supersaturation) in response to water fluxes into and out of the inland water canopies. The surface below the inland water canopy is essentially decoupled from the canopy, and hence it plays no role in the model's evolution.

Following Best et al. (2011) and as described in more detail in Wiltshire et al. (2020), land ice is represented by using the soil scheme with the soil parameters set to appropriate values for ice, i.e., the thermal characteristics are set to those of ice, whilst the other soil parameters are set to zero. This means that it is not possible to have both land ice and other surface types in the same grid box, as they share the same soil profile; hence, if land ice is present in the model, then it must cover 100 % of the grid box. Furthermore, to reduce the likelihood of small scale sharp horizontal gradients which could lead to numerical problems, only large areas of land ice are permitted in the model, e.g. in most climate simulations, only Antarctica and Greenland are included. Land ice is typically initiated at the start of integrations with a large amount of overlying snow to ensure that not all of the snow can be removed through sublimation or melt during the simulation. In addition, as the lateral transfer of snow by glacial movement is not represented in the model, it is possible to accumulate very large amounts of snow. However, this does not adversely impact on the surface energy balance. The surface temperature is not allowed to go above the melting temperature, but instead the associated energy is used to melt the snow. Infiltration of this snow melt, along with any liquid precipitation, is not permitted into the land ice, but is directed to surface runoff.

Surface fluxes are calculated separately on each tile using surface similarity theory. In stable conditions we use the stability functions of Beljaars and Holtslag (1991), whilst in unstable conditions we take the functions from Dyer and Hicks (1970). The effects on surface exchange of both BL gustiness (Godfrey and Beljaars, 1991) and deep convective gustiness (Redelsperger et al., 2000) are included. Temperatures at 1.5 m and winds at 10 m are interpolated between the model's grid levels using the same similarity functions, but a parametrisation of transitional decoupling in very light winds is included in the calculation of the 1.5 m temperature.

The roughness length for the bare soil is specified via an ancillary file that is based on Prigent et al. (2012) and the roughness lengths for all other land type are explicitly specified. Over the sea surface the COARE (Coupled Ocean–Atmosphere Response Experiment) 4.0 (Edson, 2009) momentum roughness length parametrisation is used. The drag coefficient over the sea at very high wind speeds (greater than 33 m s−1) is reduced as described in Sect. 3.1.3. The form drag for marginal ice uses the explicit representation from Lupkes et al. (2012) as described in Sect. 3.1.1.

SW radiation fluxes use a “first guess” snow-free albedo for each land surface type, which can then be nudged towards an imposed grid box mean value taken from a climatology. This nudging is not performed in either climate change simulations or any other simulations with dynamic vegetation. The grid-box mean albedo of the land surface is further modified in the presence of snow. The albedo of the ocean surface is a function of the wavelength, the solar zenith angle, the 10 m wind speed and the chlorophyll content according to the Jin et al. (2011) parametrisation. The emitted LW radiation is calculated using a prescribed emissivity for each surface type.

Soil processes are represented using a 4-layer scheme for the heat and water fluxes with hydraulic relationships taken from van Genuchten (1980). These four soil layers have thicknesses from the top down of 0.1, 0.25, 0.65 and 2.0 m. The impact of moisture on the thermal characteristics of the soil is represented using a simplification of Johansen (1975), as described in Dharssi et al. (2009). The energetics of water movement within the soil is accounted for, as is the latent heat exchange resulting from the phase change of soil water from liquid to solid states. Sub-grid scale heterogeneity of soil moisture is represented using the Large-Scale Hydrology approach (Gedney and Cox, 2003), which is based on the topography-based rainfall-runoff model TOPMODEL (Beven and Kirkby, 1979). This enables the representation of an interactive water table within the soil that can be used to represent wetland areas, as well as increasing surface runoff through heterogeneity in soil moisture driven by topography.

A river routing scheme is used to route the total runoff (from all land surface types including land ice) from inland grid points both out to the sea and to inland basins (where it can flow back into the soil moisture). If the soil at inland basin points becomes saturated and hence unable to hold more water, the resultant runoff is pragmatically redirected evenly across all sea outflow points. The resulting increase in the river outflow is always very small and does not affect the ocean salinity structure in any significant way, but importantly this process ensures global water conservation which is an important criterion for global climate models. In coupled model simulations the resulting freshwater outflow is passed to the ocean, where it is an important component of the thermohaline circulation, whilst in atmosphere/land-only simulations this ocean outflow is purely diagnostic. River routing calculations are performed using the TRIP (Total Runoff Integrating Pathways) model (Oki and Sud, 1998), which uses a simple advection method (Oki, 1997) to route total runoff along prescribed river channels on a 1° × 1° grid using a 3 h time step. Land surface runoff accumulated over this time step is mapped onto the river routing grid prior to the TRIP calculations, after which soil moisture increments and total outflow at river mouths are mapped back to the atmospheric grid (Falloon and Betts, 2006). This river routing model is not currently being used in NWP implementations of the Global Atmosphere/Land and hence any runoff is purely diagnostic and “lost” from the model's water budget.

2.12 Stochastic physics

A key component of many Ensemble Prediction Systems (EPSs) is the use of stochastic physics schemes to represent model error emerging from unrepresented or coarsely resolved processes such as numerical diffusion or fluctuations in the impact of physical parametrisations on the large-scale fields. The addition of unresolved variability around the deterministic solution adds spread between ensemble members and has been shown to improve ensemble predictions in the medium range (Palmer et al., 2009; Tennant et al., 2011) as well as on seasonal (Weisheimer et al., 2011) and decadal time scales (Doblas-Reyes et al., 2009). The increase in the model's internal variability also helps to improve the model's climatology, through a noise-drift induced process. In particular, there is strong evidence of the positive impact of stochastic physics schemes on specific processes such as mid-latitude blocking (Berner et al., 2012), the Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO, Madden and Julian, 1971; Weisheimer et al., 2014) and North Atlantic weather regimes (Dawson and Palmer, 2015).

In GA8, we use a standardised package of stochastic physics schemes (Sanchez et al., 2016) based on an improved version of the Stochastic Kinetic Energy Backscatter scheme version 2 (SKEB2, Tennant et al., 2011) and the Stochastic Perturbation of Tendencies scheme (SPT) with additional constraints designed to conserve energy and water. SKEB2 adds forcing to the large-scale flow to represent the backscatter of small-scale kinetic energy lost via numerical diffusion, whilst SPT stochastically scales the output of physical parametrisations to represent variability about their mean predictions. Despite the positive impact of model error stochastic physics schemes on EPS and climate model performance by making probability forecasts more statistically reliable and reducing the error of the ensemble mean, their formulations fundamentally add noise which degrades forecast skill when run in deterministic mode (Sanchez et al., 2016). For these reasons, these schemes are not used in deterministic forecast systems, which are designed to forecast the best possible single prediction of the atmosphere’s future state.

2.13 Global atmospheric energy correction

Long climate simulations of the Unified Model include an energy correction scheme, designed to ensure that numerical errors, inconsistent geometric assumptions and missing processes do not lead to any spurious drift in the atmosphere's total energy. The scheme accumulates the net flux of energy through the upper and lower boundaries of the atmosphere over a period of 1 d and calculates the difference between this and the change in the atmosphere's internal energy. Any drift is compensated by the addition of a globally uniform temperature increment, which is applied every time step for the following day. In GA8GL9, the magnitude of these corrections is typically W m−2.

2.14 Ancillary files and forcing data

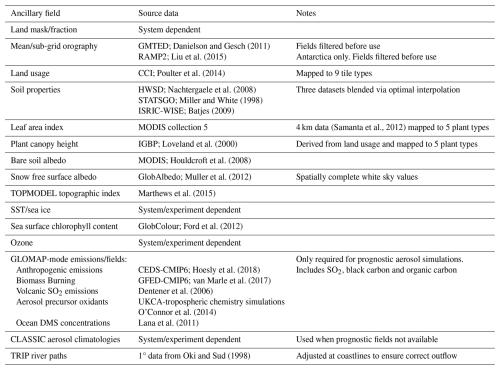

In the UM, the characteristics of the lower boundary, the values of climatological fields and the distribution of natural and anthropogenic emissions are specified using ancillary files. Use of correct ancillary file inputs can play as important a role in the performance of a system as the correct choice of many options in the parametrisations described above. For this reason, we consider the source data and processing required to create ancillaries as part of the definition of the Global Atmosphere/Land configurations. Table 3 contains the main ancillaries used as well as references to the source data from which they are created.

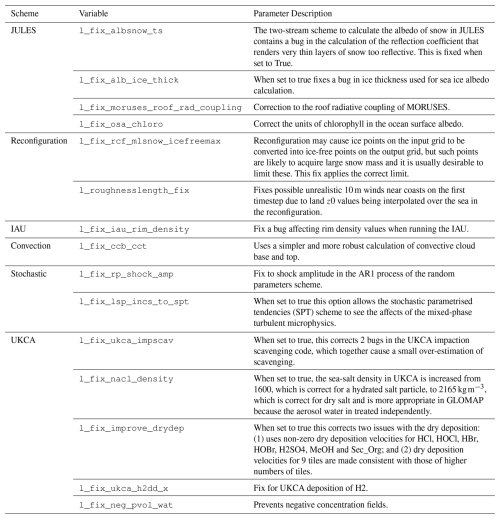

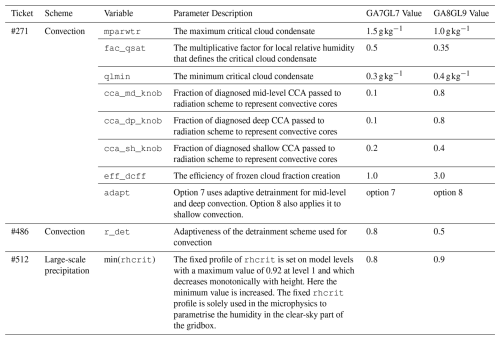

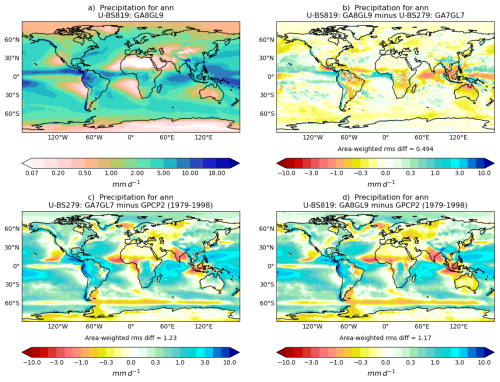

Danielson and Gesch (2011)Liu et al. (2015)Poulter et al. (2014)Nachtergaele et al. (2008)Miller and White (1998)Batjes (2009)(Samanta et al., 2012)Loveland et al. (2000)Houldcroft et al. (2008)Muller et al. (2012)Marthews et al. (2015)Ford et al. (2012)Hoesly et al. (2018)van Marle et al. (2017)Dentener et al. (2006)O'Connor et al. (2014)Lana et al. (2011)Oki and Sud (1998)The subject of this paper, GA8GL9, builds upon GA7GL7 (Walters et al., 2019) which was released in January 2016. GA8GL9 consolidates the changes made for the climate specific branch configuration GA7.1GL7.1 (Walters et al., 2019) and NWP specific GA7.2GL8.1 (Willett et al., 2023) apart from system specific tunings or where a newer science option has made change in previous branch configurations redundant. In particular the changes documented in this section with GMED tickets #192, #197, #257, #272 were originally included in GA7.1GL7.1 and those with GMED tickets #194, #207, #251, #290, #301, #324, #434, #474, #476 and #531 were originally included in GA7.2GL8.1. In addition to the consolidation of changes from the branch configuration, GA8GL9 also includes changes to most areas of the science. This section gives a description of all the changes added between GA7GL7 and GA8GL9 including those that were previously included in branch configurations.

3.1 Surface flux exchange, land surface and hydrology

3.1.1 Revised roughness parametrisation for marginal ice (GMED ticket #194)

The parametrisation of the roughness of marginal ice (i.e. the transition zone between pack ice and open sea) has been updated with the following changes being made:

-

In GL7 the exchange and drag coefficients over sea-ice were interpolated between values representative of pack ice, the marginal ice and open sea. In GL9 this is replaced by explicit representation of form drag for marginal ice from Lupkes et al. (2012), which was validated by Elvidge et al. (2016), and using the extension from Lupkes and Gryanik (2015) to account for stability.

-

The conductivity of snow on sea-ice is reduced from 0.50 to 0.256 W m−1 K−1 to be consistent with the relationship between snow conductivity and density used in the multilayer snow scheme taken from Calonne et al. (2011) and the assumed density for snow on sea ice (330 kg m−3).

-

The conductivity of sea ice is reduced to from 2.63 to 2.09 W m−1 K−1

Renfrew et al. (2019) evaluated the changes to the marginal ice drag. They demonstrated that biases and root mean square errors (RMSEs) in temperature and winds were reduced with respect to aircraft observations both over and downstream of the marginal ice zone.

3.1.2 Modifications to the rate of growth of snow grains (GMED ticket #251)

The size of snow grains affects the albedo of the snow with larger grains being darker. Earlier configurations used the parametrisation of snow grains from Marshall (1989) which was developed using continental data and did not represent the very low temperatures of Antarctica. In GL9, this is replaced by the equitemperature part of the scheme described by Taillandier et al. (2007) which predicts a slower rate of growth at colder temperatures, so increasing the albedo under typical Antarctic conditions. In addition, the calculation of the grain size during relayering of the snowpack has been modified to make it more consistent with conservation of specific surface area. Increasing the albedo over Antarctica reduces the near surface temperatures; this ultimately results in reduced circulation errors and substantially improved forecast performance in the southern hemisphere in austral summer. Increasing the albedo over Antarctica increases the error slightly relative to CERES-EBAF, but it is believed that CERES-EBAF is too dark in this region (John M. Edwards, personal communication, August 2023).

3.1.3 Improved drag at high wind speeds (GMED ticket #324)

Although the precise behaviour of the drag at high wind speeds is not fully understood, it is clear that extrapolating standard parametrisations from lower wind speeds gives excessive drag. Indeed, experimental evidence shows that the drag not only saturates at higher wind speeds but actually decreases as the wind speed increases (Donelan et al., 2004; Donelan, 2018; Curcic and Haus, 2020). This change limits the drag coefficient to when the neutral wind speed is below 33 m s−1, and gradually reduces it between wind speeds of 33 and 55 m s−1 where it reaches a limiting value of . This provides good consistency with the experimental estimates. The primary benefit of this development is seen in simulations of tropical cyclones at high resolutions where the drag is reduced and predicted wind speeds are beneficially increased.

3.1.4 GL9 drag package (GMED ticket #435)

A package of land surface changes was developed with the aim of removing the need to use an aggregate surface tile in NWP, improving the large-scale circulation and reducing the differences between the representation of the land-surface in the global and regional configurations. It is described in detail in Williams et al. (2020), but a brief summary of the changes is as follows:

-

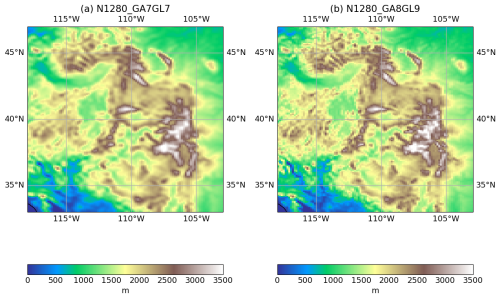

A combination of GMTED (Danielson and Gesch, 2011) and RAMP2 (Liu et al., 2015) datasets replace GLOBE30 (Hastings et al., 1999) in the generation of the orography ancillaries. A 6th order low-pass filter as described in Raymond and Garder (1988) is used to smooth the source dataset, and derive the mean and subgrid orography fields. In GL9 the filter parameters are modified so that the cut off frequency is increased and hence substantially more detail is retained in the mean orography at smaller scales (e.g. Fig. 1). The consistency between mean and subgrid orography is also improved.

-

Prior to GL9, soil roughness was set to a global constant value, i.e. z0=1 mm, but observations shows that it actually varies by orders of magnitude globally. In GL9 the single constant value is replaced by an ancillary field that is based on Prigent et al. (2012).

-

The roughness lengths for momentum for each vegetation type are now explicitly specified rather than determined by the vegetation canopy height. These specified roughness lengths were determined by rearranging the model equations to provide a relationship that depends upon the surface momentum flux and wind speed, and then optimising values for different vegetation types using observational data from FLUXNET sites (Pastorello et al., 2020).

-

The land use dataset used to generate the surface tile fractions is updated from IGBP to the newer European Space Agency's Land Cover Climate Change Initiative (ESA CCI) land-cover dataset (Poulter et al., 2014). At the same time an appropriate crosswalk table was developed to map the CCI vegetation fractions to the correct JULES vegetation tile based on Table 2 from Poulter et al. (2014). Additional changes were made so that closed trees and grasslands mapped to 100 % of the appropriate JULES tiles. Open canopies and shrubs tile fraction remained the same as the original table. Grasslands were split appropriately between C3 and C4 using data on C4 fractions from Still et al. (2003). The C4 fraction was used to identify the dominant type of grass, and then the CCI fraction was assigned to either C3 or C4 grass tiles.

-

The vegetation canopy radiation model option has been updated which provides a more realistic distribution of diffuse radiation through the vegetation canopy. The ratios of the roughness length for heat to roughness length for momentum have been updated for all vegetation types and non-vegetated surface types.

-

The orographic roughness scheme of Wood and Mason (1993) is replaced by the distributed form drag scheme of Wood et al. (2001). Both schemes are designed to represent the turbulent form drag due to small-scale sub-grid hills, but the orographic roughness approach is known to result in unrealistic low values for near-surface wind speeds over orography (Rooney and Bornemann, 2013). The distributed form drag approach reduces this detrimental impact on the near surface winds.

-

Prior to GL9, canopy snow was only applied to needle-leaved trees. In GL9 it is also applied to broad-leaved trees. As well as being more realistic, this removes an instability mechanism that was previously occasionally seen in snowy conditions when both tree types are present in the same gridbox.

Figure 1Example N1280 orography from (a) GA7GL7 and (b) GA8GL9 for a region of the eastern USA covering part of the Rocky Mountains.

The package of land surface changes reduces the errors in near-surface winds and temperatures, and hence removes the need to use an aggregate surface tile in NWP applications (Walters et al., 2017, Sect. 4.2.1), which has been a long standing difference between NWP and other applications.

3.2 Solar and terrestrial radiation

3.2.1 Liu cloud droplet spectral dispersion (GMED ticket #192)

In the model the cloud droplet effective radius is calculated as:

Where L is the cloud liquid water content, ρ is the density of liquid water, Nd is the cloud droplet number concentration and β is the spectral shape parameter, representing the degree of cloud droplet spectral dispersion. In GA7.0, β is represented by two constants depending on the cloud was over was a land (β=1.14) or ocean (β=1.08) grid-box (Martin et al., 1994), crudely representing “polluted” continental and “pristine” ocean air masses. Following detailed investigations into the aerosol effective radiation forcing (ERF) in GA7.0 (Mulcahy et al., 2018), the spectral dispersion is now calculated following the parametrisation of Liu et al. (2008), i.e.:

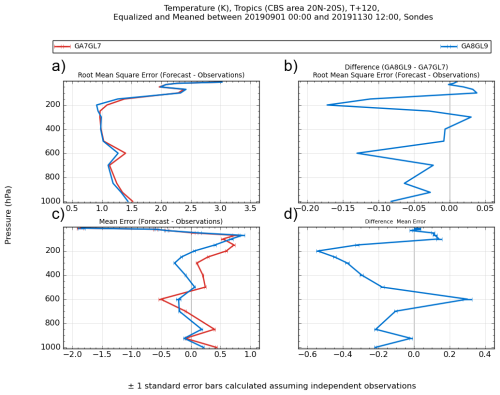

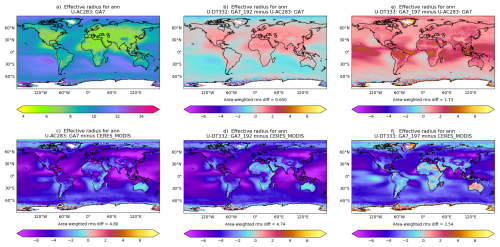

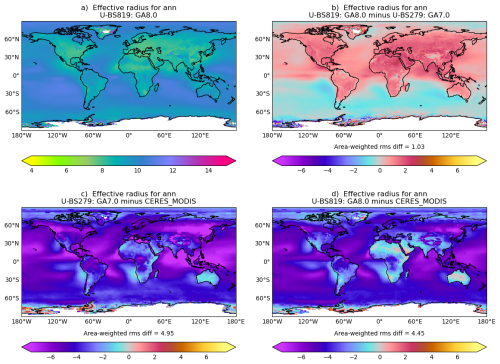

where aβ=0.07 and bβ=0.14. The impact of this change is to reduce the response of re to an increase in aerosol concentration and thereby reduce the magnitude of the aerosol-cloud albedo effect in the model, leading to a weaker (less negative) aerosol ERF in GA7 of approximately 23 % (Mulcahy et al., 2018). The effect of the Liu spectral dispersion on the cloud droplet radius and the bias relative to Clouds and Earth's Radiant Energy System (CERES) Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MODIS) is shown in Fig. 2b and d. Overall, the cloud droplet effective radius is generally increased over the northern hemisphere, where GA7 often has the most negative bias, whilst reducing over the southern hemisphere, where GA7 typically has lower negative bias. Overall, this results in the difference from the observation-based estimates becoming more spatially homogeneous.

Figure 2Annual mean cloud droplet effective radius (µm) in the 20 year N96 atmosphere/land only climate simulations compared to Clouds and Earth's Radiant Energy System (CERES) Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MODIS) showing (a) GA7GL7, (b) the effect of the Liu parametrisation (Sect. 3.2.1), (c) the effect of the improved Turbulent Kinetic Energy (TKE) diagnostic (Sect. 3.4.4), (d) the difference between GA7GL7 and MODIS, (e) the difference between GA7GL7 with the Liu parametrisation and MODIS, and (f) the difference between GA7GL7 with the improved TKE diagnostic and MODIS.

3.3 Large-scale precipitation

3.3.1 New parametrisations for riming and depositional growth of ice (GMED ticket #181)

Despite the improvements seen in GA7GL7 (Walters et al., 2019), there is still a lack of reflected SW in the Southern Ocean. It is believed that this is due to a lack of supercooled liquid water, which is a common issue in climate models (e.g. Bodas-Salcedo et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2013; Bodas-Salcedo et al., 2014). To address this issue, in GA8 the parametrisation of riming and deposition is physically improved by adding the following:

-

shape-dependence of riming rates following the parametrisation of Heymsfield and Miloshevich (2003), which was developed from aircraft observations; and

-

preventing low liquid water contents from riming based on Harimaya (1975) who showed that riming does not occur for small liquid droplets.

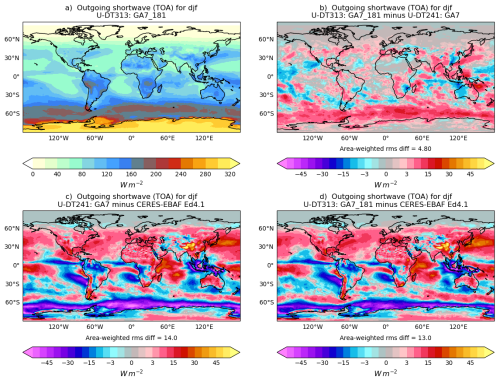

Figure 3December–February mean top-of-atmosphere outgoing SW radiation (W m−2) in the 20 year N96 atmosphere/land only climate simulations compared to Clouds and Earth's Radiant Energy System (CERES) Energy Balanced and Filled (EBAF) dataset version 4.1 (NASA/LARC/SD/ASDC, 2019) showing (a) GA7GL7 with the new parametrisations for riming and depositional growth of ice, (b) the effect of the new parametrisation, (c) bias in GA7GL7 relative to CERES-EBAF and (d) bias in GA7GL7 with the new parametrisation relative to CERES-EBAF.

Convection-permitting modelling shows that these changes improve super-cooled liquid water contents in km-scale simulations of Southern Ocean cyclones (Furtado and Field, 2017). Testing in global simulations also show increases in the liquid water content at mid- and high-latitudes and subsequent reductions in SW flux biases in the Southern Ocean (Fig. 3).

3.4 Boundary layer

3.4.1 Reduce shear-driven entrainment (GMED ticket #172)

The parametrisation of entrainment mixing across the top of convective BLs includes terms from all processes contributing to the production of Turbulent Kinetic Energy (TKE) in the BL. One of these is through shear production and the empirical coefficient in GA7 is set to 5.0, following Driedonks (1982). More recent work (Beare, 2008) has shown that in LES this term is significantly weaker and recommends a value of 1.6. This lower value is used in GA8. The impact of this change is generally small with the most notable difference being a small increase in the amount of marine stratocumulus.

3.4.2 Changes to reduce vertical resolution sensitivity in the BL scheme (GMED ticket #174)

The turbulent mixing and entrainment in cloud-capped BLs is parametrised in terms of (among other things) the strength of cloud-top radiative cooling. This is calculated within the BL scheme by differencing the LW and SW fluxes across the top grid-levels of the cloud layer. The algorithm used prior to GA8 was written when the vertical grids were relatively coarse. Single Column Model (SCM) tests with fine vertical resolution have shown this calculation can still significantly underestimate the change in radiative flux across the top of the cloud when the cooling profile is well resolved (requiring a vertical grid spacing around 50 m or finer). A new methodology identifies where the LW radiative cooling profile transitions from free-tropospheric rates above the cloud to stronger rates within the cloud, and it has been demonstrated in the SCM to be robustly resolution independent down to very fine grids (with approximately 20 m spacing being the finest tested). At standard vertical resolutions the effect of this change is very small.

3.4.3 Turn off BL mixing of ice (GMED ticket #182)

In mixed phase cloud-capped BLs ice particles typically rime supercooled water, grow and fall out of the cloud. In the model, however, there is only a single ice mixing ratio prognostic variable with which to represent the entire size distribution. This results in small ice concentrations having slow fall speeds and so are continuously returned to the cloud layer by turbulent mixing, which leads to further depletion of liquid water. Although a compromise, a better simulation of these clouds is obtained if this mixing is turned off, but limited impacts are seen in other regimes.

3.4.4 Improve the TKE diagnostic and aerosol activation (GMED ticket #197)

An estimate of TKE is calculated by the BL scheme. This is passed to UKCA Activate where it is used to calculate a vertical velocity variance (σw) that is used for aerosol activation. The following improvements have been made to this process:

-

An indexing error that erroneously shifts the value of TKE upwards by one level when calculating σw is fixed. Correcting this error will typically decrease the TKE because TKE usually reduces with height.

-

The TKE diagnostic is modified to add an explicit estimate of TKE in convective cloud thereby increasing the overall TKE. TKE is assumed to scale like convective massflux divided by convective cloud area (CCA), based on the assumption that any vertical velocity variance is due to the convective updraught. This change allows UKCA to calculate a direct estimate of σw in convective cloud. Note that this change will interact with the revised calculation of CCA described in Sect. 3.5.12.

-

The minimum value of σw used by UKCA is reduced from 0.1 m s−1, which was often being used to compensate for the lack of representation of TKE within convective cloud, to 0.01 m s−1, which is a more realistic “numerical” minimum.

The combination of these changes tends to reduce TKE which reduces the aerosol activation and cloud droplet number. The cloud droplet effective radius is therefore increased in climate simulations with the largest increases seen in deep convecting regions (Fig. 2c and f). The increase in effective radius is considered to be desirable because the effective radius in GA7 is generally lower than most observation-based estimates (although noting that MODIS, which the model is compared against in Fig. 2, is believed to have a positive bias, e.g. Fu et al., 2022). The increased effective radius darkens the clouds, and the annual mean outgoing SW is reduced by 1.5 W m−2.

3.4.5 Increase the non-linear solver term for unstable BLs (GMED ticket #290)

The puns parameter controls the BL implicit solver in unstable BLs, specifying an assumed level of non-linearity in the calculation of the diffusion coefficient in the column when the surface buoyancy flux is positive (Wood et al., 2007). Higher values of puns give greater stability but can give excessive damping. As a result, a weak non-linearity value for puns of 0.5 was used prior to GA8, consistent with the non-local nature of the diffusion coefficient calculation in unstable BLs. However, occasional failures have been seen with this setting when there is a column of extremely high winds extending well above the depth of the diagnosed unstable BL depth. The instability is likely generated above the BL where a significantly more non-linear (Richardson-number dependent) diffusion coefficient calculation is used. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that increasing puns to 1.0 greatly reduced the likelihood of this failure mechanism. Additional testing has shown negligible impact on forecast performance, including for example, in the diurnal evolution of the convective BL. For these reasons the value of puns is increased to 1.0 in GA8.

3.4.6 Improved shear-dominated BL diagnosis (GMED ticket #446)

The shear dominated BL type accounts for shear generated turbulence allowing mixing to extend into regions of weak static stability and to potentially inhibit the formation of cumulus. This change modifies the “dynamic diagnosis” of shear driven layers as applied to sea points. In particular, it requires not only that the bulk stability is near neutral (as was the case previously) but also adds the condition that cumulus should have been diagnosed. If these conditions are met, then the surface based mixed layer depth is reset to zero and cumulus diagnosis is set to false. This change addresses a problem identified with the previous “dynamic diagnosis” used in GA7 that it can limit the vertical extent of the surface-based non-local mixing in what should be well-mixed stratocumulus when surface fluxes are small. This change reduces the frequency at which the shear dominated BL type is diagnosed at higher latitudes and reduces cloud in these regions.

3.5 Convection

3.5.1 Improved convection-dynamics coupling (GMED ticket #191)

The convection scheme can sometimes become intermittent in time when the effects of convection on the environment on one timestep can spuriously prevent it being triggered on the next timestep; this is ultimately caused by the time-explicit implementation of the convection diagnosis and closure. Although real convection can be highly variable in time, the intermittency is considered to be unphysical because when averaged over the spatial scales of a model gridbox, real convection does not typically appear and disappear on the timescale of a model timestep. This intermittency is detrimental to the coupling of the convection scheme to the large-scale dynamics, e.g. it can spuriously generate vertically-propagating gravity waves in the lower-stratosphere (although real convection can do this it will be on scales smaller than a model gridbox, and this process is already represented in the model by the non-orographic gravity wave drag scheme as described in Sect. 2.7). To improve the coupling in GA8, time-damped convective increments to potential temperature, θ, and humidity, q, are passed out of the convection scheme rather than instantaneous values. This change is not intended to represent a real physical process but rather to improve the coupling between dynamics and convection, and hence to reduce the effects of the unphysical intermittency. The time-damped increments are defined as:

where is the time-smoothed increment for ϕ=θ or q, Sϕ is the instantaneous increment and τ is the damping timescale. This is discretised on timestep n as:

is the smoothed source seen by the rest of the model and is updated each timestep. The damping timescale is not physically constrained but should be as short as possible whilst being long enough to reduce the effects of the intermittency (i.e. ⪆3Δt). It is also desirable that the damping timescale is longer than the Brunt-Vaisala timescale, which is typically 15 min. Given this discussion a damping timescale of 45 min is used at all resolutions. A case could be made for reducing this timescale for higher resolutions (and hence shorter timestep) or for lengthening it for the lowest resolutions, but for the sake of simplicity, ease of implementation and consistency this has not been done. The time-smoothed increments are not advected by the large-scale flow.

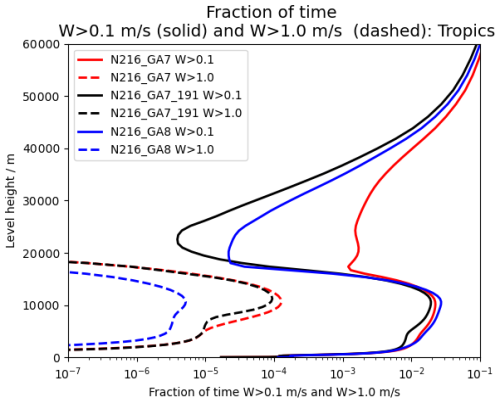

Figure 4Vertical profile showing the fraction of the time where the vertical velocity exceeds 0.1 m s−1 in solid and 1.0 m s−1 in dashed from 20 year N216 atmosphere/land only climate simulations using GA7GL7 , GA7+#191 and GA8GL9 for 20° S to 20° N.

Time-damping the convective increments greatly reduces the frequency of this spuriously generate vertically propagating gravity waves in the lower-stratosphere as can be seen by the reduction in the frequency of moderately high vertical velocities (>0.1 m s−1) in this region (Fig. 4). This change also helps to reduce the moist bias seen in the lower stratosphere and, importantly, largely removes the resolution dependence of this bias that was seen in GA7.

3.5.2 Improved computational stability in the Gregory-Kershaw type CMT (GMED ticket #198)

Kershaw et al. (2000) investigated the form of the Gregory-Kershaw convective momentum transport (Kershaw and Gregory, 1997; Gregory et al., 1997) used prior to GA8 and showed that not only was it diffusive but also that it was only computationally stable if where M is the mass flux, Δp is the pressure thickness of the layer, Δt is the convection timestep and c is positive constant multiplier for the pressure gradient term which accounts for momentum transfer between environment and updraught. Consequently, the limiting Courant number for momentum is less than one whereas for the thermodynamic variables it is one. This feature results in occasional numerical noise in the CMT increments and hence in the wind fields themselves.

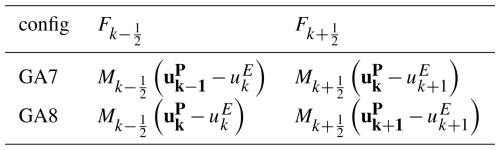

Table 4Discretisation of vertical momentum flux in GA7 (and earlier) and GA8. The modified terms are in bold

In GA8, the discretisation of vertical momentum flux is modified as shown in Table 4. This changes the condition for computational stability to which is guaranteed because the mass flux is limited to be . This change removes the noise that was occasionally seen in the CMT increments, but its wider effects are small.

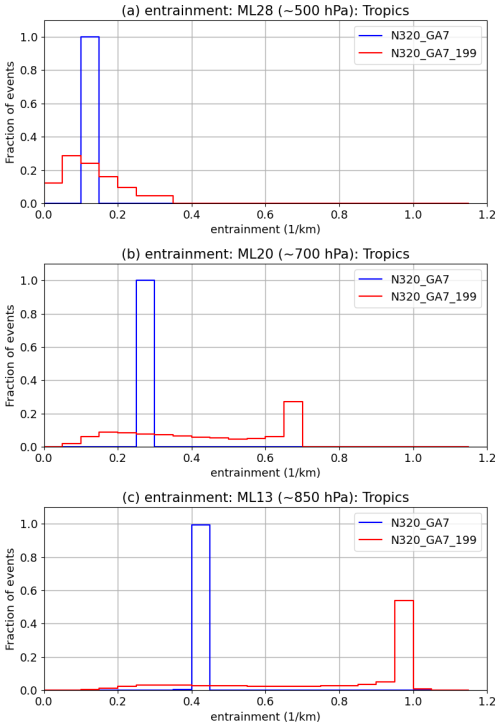

3.5.3 Prognostic-based convective entrainment rate for deep convection (GMED ticket #199)

The entrainment rate used in a convective parametrisation is an extremely important factor in determining the model's mean climate, its variability and its predictive skill. However, a single entrainment rate is not only unrealistic but can also result in a compromise between the different performance measures. Prior to GA8 once deep convection was diagnosed, fully developed deep convective clouds could instantaneously be generated (within a timestep) without the need for convection to develop and grow because it uses an entrainment rate that is appropriate for fully developed deep convection.

In GA8, we add a simple modification that allows the deep convective entrainment rate to vary over a realistic range of values by linking it to the amount of convective activity within the last several hours, as measured by a 3-dimensional prognostic based on surface convective precipitation, and on the saturated specific humidity at cloud base. Because of the dependence on recent convection, we are adding “memory” into the convection scheme. The underlying premise of the modification is that locations that have experienced high levels of recent convective activity will be populated with relatively large convective clouds that have low entrainment rates: conversely, locations that have experienced low levels of recent activity will be populated with relatively small convective clouds (if any) that will have high entrainment rates. This addition to the convection scheme is briefly described below, and a more detailed description is given in Willett and Whitall (2017).

Memory is introduced into the convection scheme via a new 3-dimensional model prognostic, , that is a measure of recent convective activity:

where is a 3-dimensional expansion of the instantaneous 2-dimensional surface convective precipitation rate and is defined as where the 3-dimensional function, C(z), is set to 1 if convection is active at a given level and 0 if it is not (here, convection is defined as being “active” on any level where the convective temperature tendency, including the contribution from downdraughts/evaporation of precipitation, is non-zero). Non-precipitating convection contributes to via a small nominal precipitation rate, pmin, which is set to 10−5 . is fully advected with the large-scale flow and, hence, it is very directly coupled to the dynamics. τ, the e-folding time, is set to 3 h (equivalent to a half life of about 2 h) and defines the timescale on which the convective system is expected to have “memory” which is not captured within the resolved fields. This timescale is broadly consistent with previous estimates of the timescales over which convection develops (e.g. Hohenegger and Stevens, 2012) and timescales over which it is expected to have memory (e.g. Davies et al., 2009).

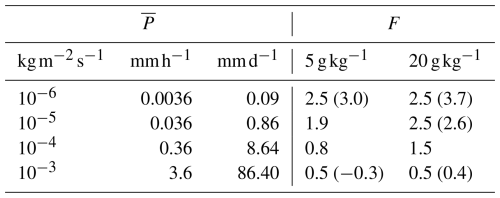

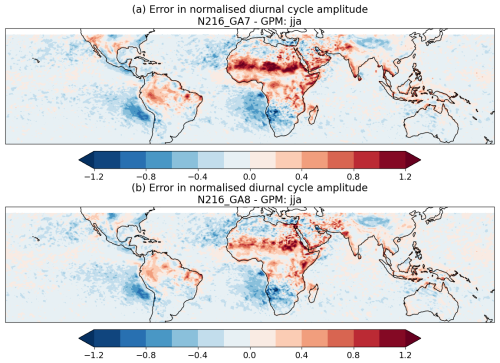

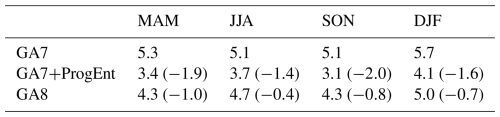

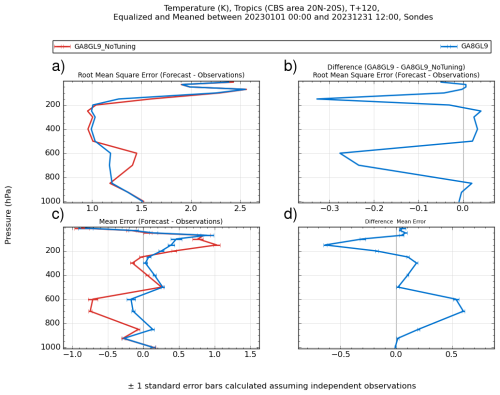

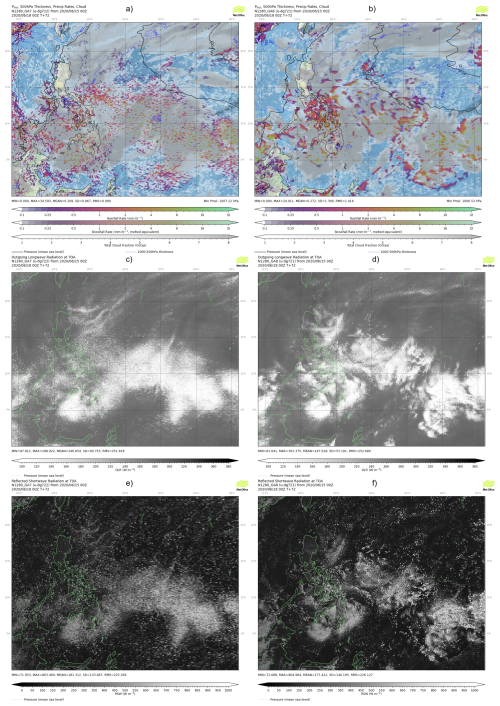

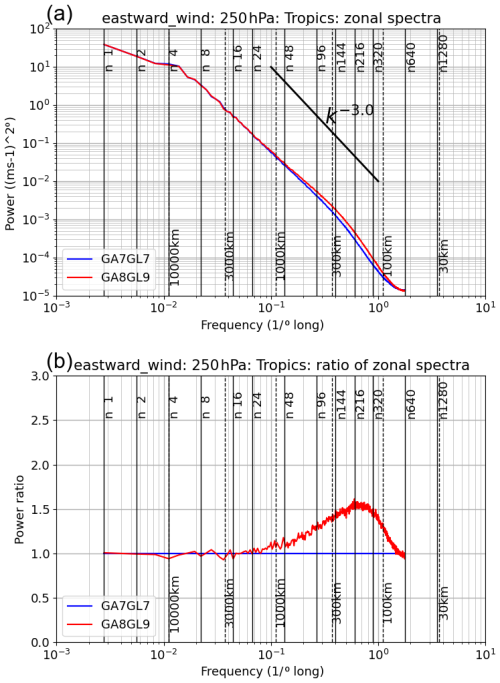

The scaling, F(z), is applied to the entrainment rate such that locations that have had relatively little recent convective activity have higher entrainment rates, and locations that have had high levels of recent convective activity have lower entrainment rates. The scaling is calculated as follows: