the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The glacial systems model (GSM) Version 25G

Lev Tarasov

Benoit S. Lecavalier

Kevin Hank

David Pollard

We document the glacial system model (GSM), which is designed for large ensemble ice sheet modelling in glacial cycle contexts. A distinguishing feature is the extent to which it addresses relevant forcing and process uncertainties. The GSM has evolved from three decades of effort to constrain the last glacial cycle evolution of each ice sheet that was present (North American, Greenlandic, Icelandic, Eurasian, Patagonian, and Antarctic, and soon Tibetan). The core ice dynamics uses a hybrid shallow-shelf and shallow-ice approximation with full thermo-mechanical coupling. It also includes one of the largest range of relevant processes for the above context of any model to date, ranging from visco-elastic glacial isostatic adjustment with 0-order geoidal deflection to state-of-the-art subglacial sediment production, transport, and deposition. Furthermore, the GSM is to date the only model to have all of the above processes bidirectionally coupled with each other. Other relevant distinguishing features include: permafrost resolving bed-thermodynamics, a fast diagnostic solution of down-slope surface drainage and lake filling, subgrid hypsometric surface mass balance and ice flow, simple thermodynamic lake and sea ice representations, subglacial hydrology with dynamically evolving partitioning between distributed and channelized flow, and surface melt that physically accounts for insolation changes via a novel insolation above freezing scheme.

To address the most challenging part of paleo ice sheet modelling, the GSM includes both a 2D energy balance climate model and variants of traditional input time series weighted interpolation (aka “glacial indexing”) of fields from General Circulation Model (GCM) simulations, all under ensemble parametric specification. It also includes options for one and two way scripted coupling with climate models.

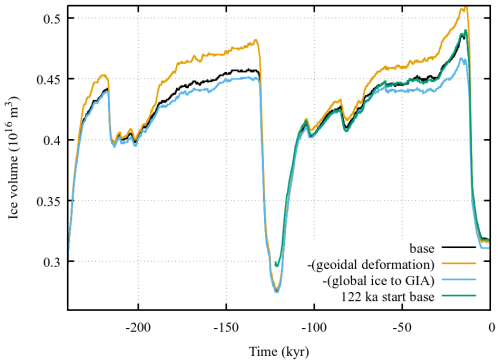

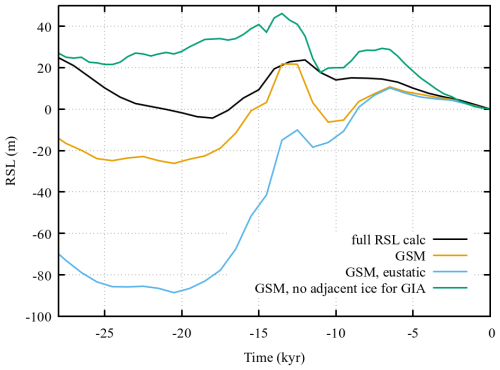

We demonstrate the significant errors that can ensue in the glacial cycle simulation of a single ice sheet when three aspects of glacial isostatic adjustment are ignored (as is typical). These are geoidal deformation, global ice load input, and correction of initial topography for present-day isostatic disequilibrium. We also draw attention to the relatively high sensitivity of the GSM (and presumably other ice sheet models) to the specification of the temperature dependence for basal sliding activation.

The associated code archive includes configuration options for all major last glacial cycle ice sheets as well as idealized geometries and validation test setups.

- Article

(2870 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1483 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Paleo ice sheet modelling contexts have some features that impose distinct requirements in comparison to models designed for present-day and near future centennial scale modelling. For the latter, certain processes, such as subglacial sediment production, transport, and deposition, are effectively irrelevant (given their much longer characteristic time-scales, e.g., Drew and Tarasov, 2024), and others, such as glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA), can be more simply or more carefully approximated, depending on context and simulation time interval (Whitehouse et al., 2019). Furthermore, given the large uncertainties in climate forcing over a glacial cycle, ice sheet modelling for the purpose of constraining past ice sheet evolution requires large ensembles of simulations with adequate degrees of freedom in the climate forcing. This along with the O(100 kyr) glacial cycle timescale implies that computational costs are a much more critical consideration for paleo ice sheet modelling as compared to present-day modelling contexts.

Other potentially critical processes and feedbacks for glacial cycle contexts that are typically ignored for present-day ice sheet modelling include the following: the evolution of proglacial lakes and their impact on ice sheet mass loss (e.g., Tarasov and Peltier, 2006), the evolution of landfast perennial lake and sea ice into ice shelves and ice tongues (e.g., Bradley and England, 2008), the evolution of geothermal heat flux and permafrost depth and their impact on basal thermal energy balance (e.g., Tarasov and Peltier, 2004), and the impact of changing insolation (due to orbital forcing) on surface melt (e.g., van de Berg et al., 2011).

The Glacial Systems Model (GSM) is a numerical model for simulating ice sheets and their interactions with the rest of the Earth system over glacial cycle time-scales. It features fully coupled components relevant to this context that explicitly model all of the processes and feedbacks listed above. To date, such a complete set of components is not found in any other ice sheet model (various current models used for paleo ice sheet modelling have many, but not all of the GSM features, e.g., Winkelmann et al., 2011; Sato and Greve, 2012; Pollard et al., 2015; Quiquet et al., 2018; Robinson et al., 2020; Berends et al., 2022). For instance, the GSM is the only current ice sheet model that can resolve englacial sediment transport and subglacial sediment production due to quarrying (with otherwise only Pollard et al., 2015, having even a representation of subglacial sediment transport). Furthermore, no other model has a sediment process model fully coupled to glacio-isostatic adjustment (albeit asynchronously).

A key and distinguishing GSM design consideration is a focus on uncertainty quantification. This entails parameterization of as many significant glacial system uncertainties as is reasonably possible, given the much greater challenge in assessing structural modelling uncertainties. This results in the GSM currently having a minimum of 30 (Patagonia) to a maximum of 53 (North America) ensemble parameters for a single paleo ice sheet. In contrast, all previous paleo ice sheet modelling studies not using the GSM (or its precursor, Tarasov and Peltier, 2004) use fewer than 7 parameters (e.g., Albrecht et al., 2020a, use 4 ensemble parameters for ensemble modelling of the last glacial cycle Antarctic ice sheet). The GSM also has noise insertion options for partial quantification of structural uncertainties (i.e., model uncertainties not captured by ensemble parameters, a feature shared by only one other ice sheet model, cf. Verjans et al., 2022).

Given the large ensemble requirement for paleo ice sheet modelling, the GSM is highly optimized for serial computation. For instance, a 205 kyr Antarctic simulation at 40 km resolution taking about 10 h on a (circa 2016) single Intel Xeon E5-2650 (2.3 GHz) core. The lack of parallelization limits spatial grid resolution to about 10 km for continental scales, with 0.5° by 0.25° longitude by latitude being the current default. However, to partially compensate for limited spatial resolution, the GSM includes a state-of-the-art subgrid hypsometric surface mass-balance and ice flow model (Le Morzadec et al., 2015).

Another important feature is that the model has been configured for all but one of the last glacial cycle ice sheets (including Antarctic, Greenland, North American, Eurasian, Icelandic, Patagonian, and soon Tibetan), and includes options for one and two way coupling with external climate models. The GSM's internal climate representation enables full Pleistocene simulations of Northern Hemispheric ice sheets in approximate accord with inferences for past sea level from benthic δ18O records with simulations only driven by orbital and greenhouse gas forcing (Drew and Tarasov, 2024).

The GSM has a long history (going back to the purely shallow ice approximation version in Tarasov and Peltier, 1997a), with a significant change being the incorporation of the Pollard et al. (2015) ice dynamical core for inclusion of shallow shelf physics completed in 2017. The current form of the GSM largely matches that used for publications using the GSM from 2020 onwards with a chronology of relevant changes summarized in the Supplement. Though the model continues to evolve, it is now at a stage and in a form appropriate for initial public release. Below we document the GSM and provide example test results of the impact of some of its relatively unique features.

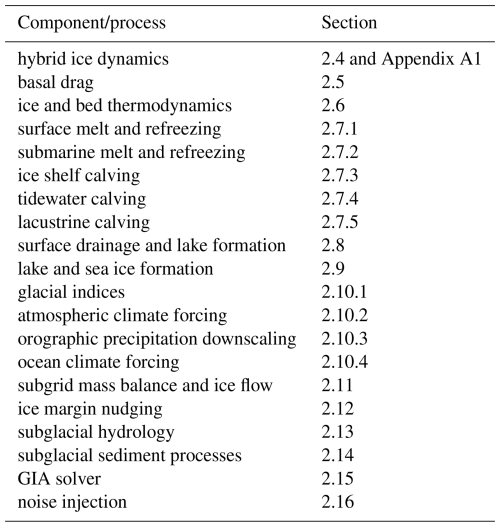

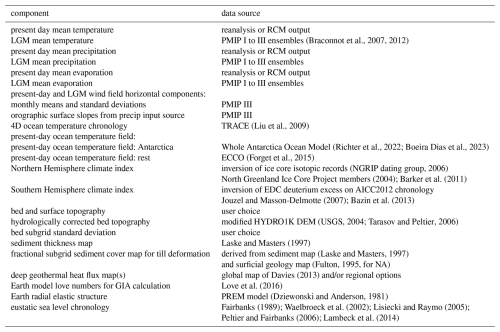

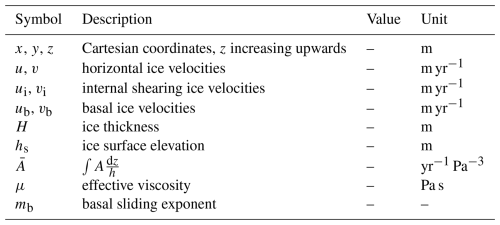

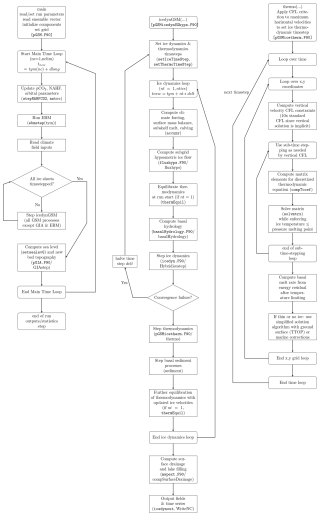

The GSM includes a number of distinct, fully coupled components (cf. Table 1 and Fig. 1). The hybrid shallow-shelf/shallow-ice (SSA/SIA) dynamical core (Sect. 2.4 and Appendix A1) is a modified version of the Penn State University 3D (PSU3D) ice sheet model (Pollard and DeConto, 2012; Pollard et al., 2015; Pollard and DeConto, 2020). This dynamical core includes a grounding line flux parameterization (Schoof, 2007; Pollard and DeConto, 2020) and is able to capture marine ice sheet instabilities (Pollard et al., 2015). The main differences from that of Pollard et al. (2015) are conversion to Fortran 90 standards, the addition of the NSPCG generalized numerical solver (Kincaid et al., 1989) for solving the SSA stress-balance, separate basal drag laws for soft and hard beds (Sect. 2.5), the addition of an alternative grounding line flux parameterization (Tsai et al., 2015), a few minor bug fixes, and changes to the iterative SSA solution to further optimize speed and numerical stability while allowing recovery from iterative convergence failures.

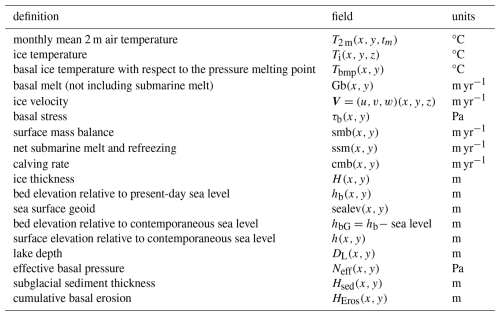

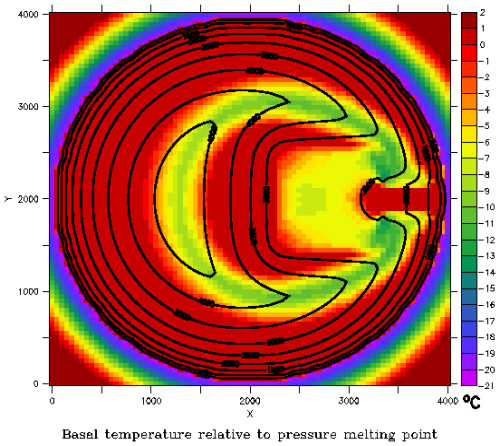

Figure 1GSM key components and process linkages indicating key variables passed. Variable names are as follows. H is ice thickness, hb is bed elevation relative to contemporaneous sea level, Hhb is mix of H, hb, and surface elevation. H is only updated in the ice dynamics module, but to minimize clutter, H is shown as flowing through the GIA solver (the latter also uses H as an input). DL is lake depth, mb is mass-balance components (melt, accumulation, and calving), SSM is submarine melt, Gb is basal melt, Neff is basal effective pressure, Ti is ice temperature, Vice is the 3D ice velocity field, Hsed is subglacial sediment thickness, and “Eros” is basal erosion. All passed variables are mean annual (or longer) except for mean monthly climatology atmospheric climate inputs for the surface mass balance component: 2 meter air temperature (Tair), precipitation (Prec), net evaporation (Evap), horizontal wind velocity field (Vwind) used for orographic downscaling of precipitation, and surface insolation (Insol). To avoid clutter, the subgrid mass balance and ice flow component is not shown, but spans the surface mass balance and hybrid ice dynamics components.

The ice thermo-dynamics (Sect. 2.6) is an energy-conserving finite-volume formulation (Patankar, 1980). The bed thermodynamics (Sect. 2.6) resolves permafrost and includes corrections for seasonal snow cover over ice-free land (Tarasov and Peltier, 2007).

The GSM has an asynchronously coupled global visco-elastic isostatic response GIA solver (Tarasov and Peltier, 1997b) with a linear approximation for the deflection of the geoid (with space-time dependence) from a spherically symmetric eustatic mean sea level anomaly (Sect. 2.15).

Surface drainage (Sect. 2.8) is diagnostically resolved using a down-slope formulation that fills topographic depressions (lakes) while maintaining mass-conservation (Tarasov and Peltier, 2006). The resolving of pro-glacial lakes permits inclusion of a simplified lake ice parameterization (Sect. 2.9) and a fresh-water calving component limited by available lake heat (Sect. 2.7.5). Surface melt includes a novel positive degree solar insolation component (Sect. 2.7.1). Subshelf melt and freeze-on uses a buoyant plume parameterization (Sect. 2.7.2), while calving parametrically accounts for crack propagation, hydro-fracturing, and strain (Sect. 2.7.3 and 2.7.4) enabling the capture of marine ice cliff instabilities.

For climate forcing, the GSM simultaneously uses glacially-indexed (Sect. 2.10.1) GCM snapshots and an asynchronously-coupled, geographically-resolved, energy balance climate model with non-linear snow and sea ice albedo feedback (Sect. 2.10.2). Precipitation is subject to wind-climatology driven orographic forcing to account for the strong impact of orography (Sect. 2.10.3). The default ocean temperature forcing uses results from a transient deglacial GCM simulation (TRACE Liu et al., 2009), again subject to glacial indexing (Sect. 2.10.4).

Other optional components include the following. The GSM has several fully coupled basal hydrology representations (Sect. 2.13 and Drew and Tarasov, 2023) and a state-of-the-art subglacial sediment process model (Sect. 2.14 and Drew and Tarasov, 2024). There is a subgrid hypsometric surface mass-balance and ice flow model to partly compensate for coarser grid resolution (Sect. 2.11 and Le Morzadec et al., 2015). There is the option of nudging surface mass balance and calving to facilitate consistency of simulated and geologically reconstructed ice margin locations (Sect. 2.12). Finally, the GSM includes a compile flag for activating stochastic noise additions to poorly constrained processes in the model (Sect. 2.16).

Relevant details on each component are provided in the indicated subsections (Table 1). A summary log of key 2023 to 2025 GSM version changes is in Sect. S3 of the Supplement.

2.1 GSM grid and structure

The GSM is mostly coded following Fortran 90 conventions and formatting, including the use of modules and implicit none (the latter requires each variable to be explicit declared). A few legacy components, including the coupled energy balance climate model (EBM) have yet to be brought to this standard. Numerous configuration options are under compile flag control.

The GSM has an ice sheet index dimension allowing separate ice sheet domains instead of, for instance, requiring a grid covering the whole globe. There are 3 horizontal grid options: regular dx,dy; regular longitude, latitude; and polar stereographic projection, with the option of the latter two running concurrently for different ice sheets. All GSM components will use the same horizontal grid for a given ice sheet except for the GIA solver and EBM which use (global) spherical harmonics. However the GSM uses different vertical grids for ice temperature, bed temperature, and ice dynamics.

As significant changes in the vertical temperature gradient are possible at any relative depth (e.g., Cuffey and Paterson, 2010), the vertical ice temperature grid is a standard sigma grid. It has default 65 layers (GSM parameter NCZ) with a vertically-split basal cell to more accurately compute basal melt. As changes in the vertical gradient of horizontal ice velocities are concentrated near the bed, the GSM uses an irregularly spaced sigma grid for the ice dynamics solver with high resolution near the bed (with default NLEV = 12 layers). Velocities and temperatures are transferred to each other's grid by linear interpolation. As is fairly standard, the ice sheet model uses an Arakawa C-grid, with fluxes and velocities computed on grid cell interfaces.

The bed thermodynamic grid has exponential spacing in accordance with diffusion scaling. It has a default 26 layers (GSM parameter NTBZ) and scaling exponent value of 1.21 (GSM parameter RbedSCALE) for a default 4 km deep bed.

2.2 GSM parameters

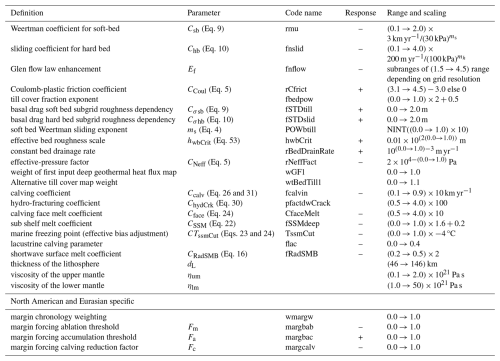

Any complex geophysical model will have a host of poorly constrained parameters that significantly impact model simulations. To address this, the GSM has a comparatively large set of ensemble parameters (Tables 2 and 3) that define the parametric configuration for a given run. This is in contrast to “GSM parameters” denoting parameters set to fixed values based on physics or relative model insensitivity to the parameter (Table 4). The selection of the ensemble parameters has been refined during the course of decades of calibration and sensitivity analysis (e.g. Tarasov and Peltier, 2004; Tarasov et al., 2012).

While each paleo ice sheet will have some specific ensemble parameters, the majority of parameters are common across ice sheets. The majority of ensemble parameters are scaled to give a 0→1 input range. However, others that have a somewhat clearer physical interpretation may have a different scaling. To ensure a reasonably comparable scale, all ensemble parameters are subject to the following scaling rules. First they must be greater than or equal to 0 and less than 10. Second, the parameter range must be greater than 0.1. Some ensemble parameters (e.g., hwbCrit in Table 2) may be scaled exponentially to permit a nominal 0→1 range.

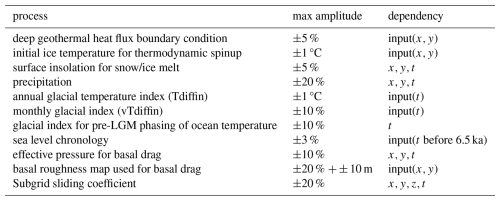

Table 2Ensemble parameters not related to climate forcing. Input parameter ranges are given by the (a→b) specification with subsequent scaling/shifting as indicated. The sign in the response column indicates the typical LGM ice volume response to an increased value of the parameter based on sensitivity tests or a priori reasoning when straightforward. It should be noted that opposite responses are possible for some of the parameters depending on the whole parameter vector value. “LGM” is last glacial maximum.

Table 3Climate forcing ensemble parameters. Parameter scalings follow the same rules as described in Table 2.

Given the nonlinearities in the system, ensemble parameter sensitivities are assessed by automatic relevance determination (Neal, 1996) during the history matching iterations for each paleo ice sheet. For the purposes herein, a simple one at a time parameter sensitivity analysis is provided in the Supplement for the Greenland (GRIS), North American (NAIS), and Antarctic (AIS) ice sheets. Collectively, these demonstrate that each ensemble parameter has significant impact for at least one metric component.

2.3 A caveat on parameterizations in the GSM

Given the breadth of applications the GSM has, or is, being used for (all last glacial cycle ice sheets from Icelandic to Antarctic), and the dimension of the ensemble parameter space and range of climate inputs used; there is no such thing as an optimal parameterization. A further complication is the over two decades of continuous development. Optimal fits from earlier GSM versions may no longer be optimal given changes in input topographies, climate inputs, etc.… As such, the approach has been to combine physical reasoning, parametric forms from the literature, and broaden degrees of freedom across various components to albeit incompletely convert process uncertainties into ensemble parameter uncertainties.

2.4 Ice dynamics

The hybrid SSA/SIA solver was imported from Pollard and DeConto (2012) and thereby uses the identical finite difference discretization. This discretization naturally imposes the appropriate stress balance boundary condition for a floating ice margin (cf. e.g., Cuffey and Paterson, 2010; Winkelmann et al., 2011). Aside from conversion to F90 standard, the main change after import was the insertion of a sequence of matrix solver options for the SSA equations in case of convergence failure. First, a biconjugate gradient squared solution (BCGS option for the NSPCG solver) is attempted. Upon failure, a generalized minimal residual (GMRES) solution is subsequently attempted. Upon further failure, successive over relaxation (SOR) will be tried. The first two options use a symmetric successive over-relaxation preconditioner (SSOR). If convergence failure persists, the GSM steps back to the beginning of the last dlong interval (default 100 years) and the time-stepping is repeated with half the ice dynamical time-step (delt). The short time-step is retained for at least three hundred years and then reverts back to the previous value when permitted by the CFL (Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy) criterion.

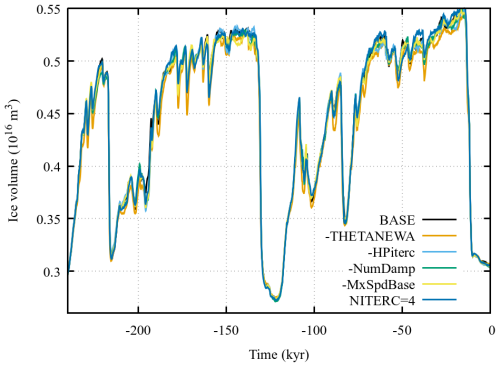

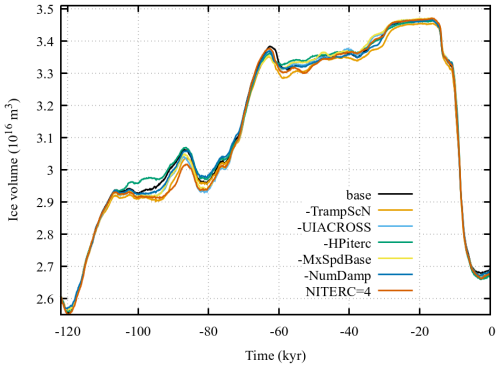

The solution of the hybrid SSA/SIA equation involves an outer Picard loop (1:NITERC) for ice thickness and a sequence of two inner loops (1:NITERA) to solve the SSA elliptic equations for the horizontal ice velocities (cf. Appendix A1), first without the grounding line flux condition, then with it. Default convergence thresholds are 0.5 % and 2 m yr−1 respectively for the maximum grid cell residuals between successive iterations. For the default compile flags, the outer Picard iteration is subject to 10 % damping of the first iteration (-DNumDamp) and to the unstable manifold correction of Hindmarsh and Payne (1996) for all but the last iteration (-DHPiterc). Sensitivities to these numerical compiler flag options for example GRIS and AIS glacial cycle simulations are in Appendix B.

The default choice for the stopping criteria for the SSA elliptic matrix solution (say of the form Au=b) is the relative norm (option 10 of the NSPCG package, Kincaid et al., 1989) of the left pre-conditioned residual (for a preconditioner matrix that can be split into left and right components Q=QLQR):

Convergence thresholds (ζ) are a function of the iteration, with final iteration thresholds of or smaller.

In addition to the default grounding line ice flux treatment of Schoof (2007) for Weertman type sliding, we've added a Coulomb-plastic option from Tsai et al. (2015). The grounding-line ice thickness for the flux calculation is determined via a subgrid interpolation as in Pollard and DeConto (2012). The treatment of 2D buttressing effects on grounding line fluxes in the GSM has been revised as per Pollard and DeConto (2020). This addresses limitations of the original (Pollard and DeConto, 2012) approach when compared against the results of an Antarctic ice sheet model with a highly resolved computational mesh around grounding lines (Reese et al., 2018).

The only other significant ice dynamical differences from Pollard and DeConto (2012) are the specification of basal drag and basal sliding activation as detailed below (Sect. 2.5) and a correction to handle a floating ice margin that subsequently becomes grounded on what was previously ice free terrestrial land (an atypical situation, that was found to occur in Northern Baffin Bay for some GSM glacial cycle simulations).

The GSM uses a default Glen flow law (exponent 3 stress dependence) ice rheology (Glen, 1952; Cuffey and Paterson, 2010). However recent work has favoured an exponent 4 for ice sheet contexts (Fan et al., 2025), though curiously it has chosen to ignore evidence for grain boundary sliding being the rate-limiting process with exponent 1.8 for typical ice sheet stress regimes (Goldsby and Kohlstedt, 2001; Peltier et al., 2000). Furthermore, for temperate ice with >0.6 % liquid water content, laboratory experiments indicate a linear viscous rheology dominates due to diffusion creep (Schohn et al., 2025). To address this uncertainty, the GSM flow law exponent is a free parameter with a compile flag option (-DPOWiceEns) to convert it to an ensemble parameter. However, this will entail user coding of an appropriate temperature dependent flow coefficient for the chosen exponent.

The default Glen flow law dependence on ice temperature follows the recommended values of Cuffey and Paterson (2010). An ensemble parameter (Ef) provides the default flow enhancement. The basal ice layer in the model is given an extra 50 % enhancement to partly capture the observed lower effective viscosity of older basal ice (Cuffey and Paterson, 2010). As well, the enhancement in the upper half of the ice column is reduced by 50 % to partly account for the reduced fabric development in younger ice (Cuffey and Paterson, 2010).

Ice flow enhancement in the GSM also partially accounts for anisotropic effects from fabric development in polar ice (Ma et al., 2010). This fabric development tends to stiffen the ice with respect to horizontal strain. As the traditional Glen flow law enhancement factor in good part represents the enhancement in vertical shear due to this fabric development, it stands to reason that for horizontal strain, this factor should take on some sort of inverse relation to the SIA enhancement. Invoking Occam's razor to give a functional form of , along with the requirement that the SSA enhancement and from Ma et al. (2010), the SSA enhancement factor for ice shelves is therefore

For ice streams, Ma et al. (2010) recommend a value of 1 at the onset, and the ice shelf value at the grounding line. To avoid the required relative position tracking, an average value of

is applied. The above ignores uncertainties in the relation between SIA and SSA flow enhancements, and therefore warrants future investigation. However for now we judge that such uncertainties are swamped by other relevant sources, especially those due to climate forcing controlling surface and basal (for ice shelves) mass-balance.

2.5 Basal drag

Given the uncertainties in the appropriate form of the large scale basal drag law for soft bed (e.g., Fowler, 2003), the GSM has both Weertman power law and Coulomb plastic options for soft-bedded basal drag. For the Weertman case, the effective basal sliding law (for both hard or soft beds) is given by (e.g., Weertman, 1957; Cuffey and Paterson, 2010):

with basal drag τb and basal velocity Ub. Cb incorporates a basal temperature ramp for sliding activation (cf. Sect. 2.5.2). Cb also accounts for: (i) potential subgrid warm based conditions in topographic lows, (ii) bed type (soft or hard), and (iii) drag reduction under pinned shelf conditions (as detailed below). The exponent (mb) is generally treated as an ensemble parameter (mb=ms in Table 2) when the bed has deforming till cover given the range of inferred values in the literature (e.g., Gillet-Chaulet et al., 2016; Maier et al., 2021).

The -DNeffDRAG compile flag combined with any form of basal hydrology imposes basal effective pressure dependence on the basal drag. When activated, the Weertman basal sliding coefficient is multiplied by the following to give a regularized form of the traditional basal effective pressure dependence (cf. e.g., p. 240 of Cuffey and Paterson, 2010):

where Neff is the computed effective basal pressure (cf. Sect. 2.13), is an ensemble parameter scaling coefficient, and the regularization parameter Nreg has value 10 kPa.

Based on the results of a basal drag inversion for Greenland (Maier et al., 2021), the hard bed has a default power law exponent mb=4 but otherwise has the same form of Weertman type sliding law as for soft-bedded Weertman (Eq. 4). This sliding exponent value is in agreement with recent evidence in favour of an exponent 4 stress dependence for ice flow (Fan et al., 2025) if basal sliding is dominated by ice deformation around obstacles. Given the high statistical confidence in the results of the above inversion for the 4 (of 8 total) catchments with mostly strong (hard) beds, we tentatively assume this value is appropriate for all other paleo ice sheets. If there was evidence or judgment to the contrary, turning this exponent into an ensemble parameter would be trivial.

For Coulomb plastic basal drag, a regularized form that accounts for cavitation (similar to that of Schoof, 2005; Joughin et al., 2019) has been found to have better numerical convergence:

where CCoul is a drag coefficient, UsqReg is a regularization velocity term ((20 m yr−1)2) and ϕt is the elevation dependent friction till angle (as per Maris et al., 2014) to account for the increased prevalence of saturated fine sediment cover in marine sectors:

where hbG is the bed elevation relative to contemporaneous sea level. This formulation uses an appropriate linearization around the previous value of the basal velocity () in the iterative solution of the SSA velocity equation:

If the computed Coulomb plastic basal drag is greater than the Weertman basal drag (pre-computed using an SIA approximation for drag law selection only), then the latter basal drag law is used instead. This has both a physical motivation (at high effective pressure and warm-based conditions, Weertman sliding is plausible, e.g., Tsai et al., 2015), and a numerical motivation (ensuring the basal drag is never larger than the sum of remaining horizontal stresses).

The Coulomb plastic option is more numerically unstable, and as such, a high exponent Weertman law (e.g., exponent 7) is recommended in lieu when computational resources are a limiting factor.

2.5.1 Basal drag geological and subgrid topographic controls

The GSM requires a specification of the fractional soft bed cover for each grid cell, either as a constant input (Table 6) or dynamically determined (Sect. 2.14). The determination of soft/hard bed is set according to whether the fractional soft bed cover of the grid cell is above or below GSM parameter SEDCUT (default 0.5). A future improvement will be the inclusion of fractional basal drag from both hard/soft bed components. As the basal drag is computed at grid cell interfaces, the sediment fraction at the interface must be set. This is taken as the square root of the product of adjacent sediment cover fractions in partial accord with a self-consistent treatment for setting diffusion coefficients in a discretized linear diffusion process (the square root operation was chosen to provide an intermediate between an arithmetic mean and the appropriate harmonic mean, cf. Patankar, 1980).

One to date unresolved issue is how to deal with fractional and thin till cover as well as the impact of different classes of sediments. The default approach in the GSM is to set the local sediment fraction coefficient (sedF in Eqs. 9 and 10) to the minimum of 1.5 and 2× the input sediment fraction for regions that are presently marine and otherwise to the input value raised to the power of the ensemble parameter fbedpow. This is intended to crudely account for the likely lower drag from marine muds and otherwise provide some ensemble parametric control.

Another unresolved issue for basal drag is the appropriate accounting for the impact of subgrid bed roughness, especially for typical paleo ice sheet model grid resolutions of 10 km or more. Presumably a rougher bed will increase basal drag, with bedrock exposures acting as pinning points. However an opposing mechanism could also be argued with a rough hard bed promoting the trapping of soft subglacial sediment. Past studies of the impact of bed roughness on basal drag typically only consider metre or less bed roughness (e.g., Gagliardini et al., 2007; Wilkens et al., 2015), Though there have been some detailed relationships proposed based on single basin scale analysis (e.g., Li et al., 2010), their validity for continental scale applications are unclear and furthermore their data input requirements (metre scale bed topography) are unlikely to be met for the global ice sheet context in the foreseeable future. To address some of these uncertainties, in addition to ensemble separate parameter sliding coefficients for hard and soft beds (Csb and Chb), two ensemble parameters (Cσsb, Cσhb) impose Weertman basal drag dependencies on the subgrid standard deviation of bed elevation (σb in m). For soft beds, this takes the form of a basal sliding coefficient:

For hard beds, an adhoc term accounting for the subgrid fraction of soft bed cover (sedF) is also included:

The GSM has not been set up for present-day inversion of a basal drag map for existing ice sheets. For paleo contexts, such inversions are problematic given the confounding impacts of changes in basal water pressure and basal sediment thickness. Nor can such inversions provide a value where the bed is currently frozen. There is a need for the development of robust basal drag parameterizations that can be applied to all paleo ice sheets, be it for regions that are presently subglacial, marine, or subaerial.

A key issue for ice shelf modelling is the presence of potential subgrid pinning points under the ice shelf that aren't presently active. This is a significant source of uncertainty given the lack of detailed topographic data for the subshelf environment. To partly address this, the model has a standard option of assuming a Gaussian distribution of subgrid pinning points based on a map of the standard deviation of the subgrid bed elevation. For poorly observed regions, adjacent open marine environments can provide an estimate when creating these maps. The pinning point effect is simply imposed as a fractional coefficient (fpin <1) that multiplies the basal drag derived as if the shelf was grounded. fpin is set to the cumulative normal distribution (more exactly an analytical approximation thereof) for subgrid elevation above the distance between the bed and ice shelf base. For distances of more than 3 standard deviations of basal roughness, fpin is effectively set to 0 (an unpinned ice shelf with a very small basal drag (0.001 Pa (m/yr)−1) to avoid singularities in the stress balance matrix).

2.5.2 Basal sliding activation

A key issue that most ice sheet models do not explicitly address is the appropriate activation function for basal sliding as warm-based conditions are approached. A detailed resolution scaling analysis of this issue has recently been published (Hank et al., 2023), and its recommended activation function is under compile flag choice (-DTrampScN). Briefly this is implemented via an estimated warm-based fraction of a grid cell Fwarm (also indirectly accounting for sub-temperate sliding, e.g., Fowler, 1986):

where Tbp,I is the grid cell interface basal temperature relative to the pressure melting point. Tramp is the temperature interval for which the grid cell has some warm-based subgrid ice and Texp is the exponent used for the ramp. On the basis of numerical experiments, resolution dependence is minimized for values of Texp between 5 and 10 (Hank et al., 2023), with the GSM having a default value of 10. This ramp depends on the subgrid standard deviation of elevation (σhb, in metres) given that a higher standard deviation can increase the subgrid fraction at the pressure melting point when the nominal grid cell basal temperature is below the pressure melting point. As such and with explicit dependence on grid cell resolution (Δxy), Tramp is given by:

This choice of resolution dependence (as determined in Hank et al., 2023) leads to a sharper temperature ramp for finer horizontal grid resolutions, as would be expected on physical grounds (since the range of subgrid basal temperatures for a grid cell, when not fully warm-based, will generally be larger for a larger grid cell). The subgrid warm-based fraction Fwarm then enters into the basal drag coefficient Cb (cf. Eq. 4) as following:

Cfroz is the fully cold-based sliding coefficient for numerical regularization:

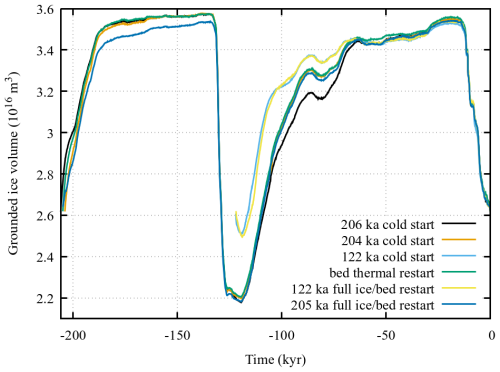

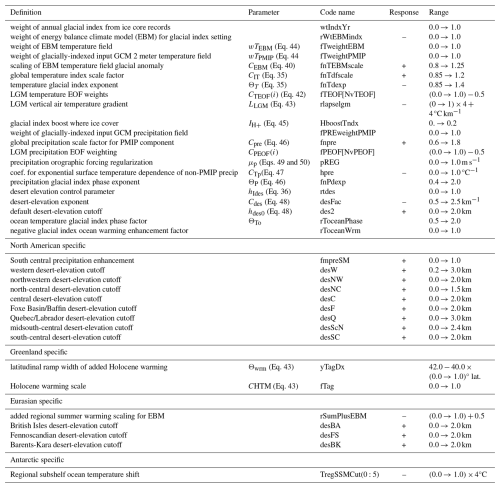

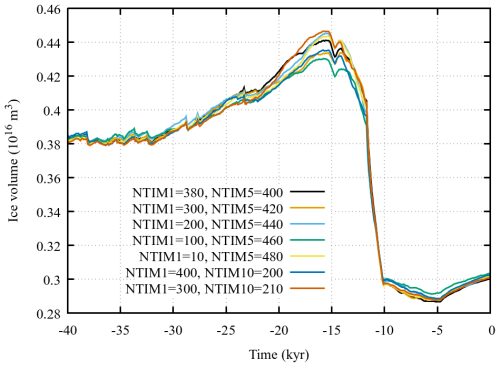

The detailed analysis of ice sheet model sliding activation specification in Hank et al. (2023) focused on surge cycling in an idealization of Hudson Bay and Hudson Strait. It did not consider other paleo ice sheets. For an example GRIS simulation, the ice volume response to the width of Tramp in Eq. (11) is very strong (Fig. 2), especially when compared to the minimal response to other numerical compiler flags (Fig. B1). It is also one of the more sensitive numerical flags for an example AIS simulation (Fig. B2). This further underlines the importance of a numerically and physically justified specification of basal sliding activation.

Figure 2Example GRIS ice volume history sensitivity to the width of the basal sliding activation temperature ramp (Tramp) in Eq. (11). The simulations use the default 0.5° by 0.25° (longitude, latitude) resolution.

Another non-trivial issue for ice sheet models with continental scale grids is the appropriate determination of the basal interface temperature. The preferred approach in the GSM accounts for the potential warming at the warm-cold interface by refreezing of subglacial meltwater. This is approximated (with -DTbpmGbI) by using half of the latent heat flux embodied in subglacial meltwater generated by the two grid cells bordering the cell interface under question. This latent heat is distributed across the basal ice dynamical layer to convert to a temperature increment and added to the interpolated basal temperature at the interface. Hank et al. (2023) provides a detailed description and comparison of this and alternative treatments for computing the basal temperature at the grid cell interface.

2.6 Ice thermodynamics and permafrost resolving bed thermodynamics

The GSM finite volume thermodynamic scheme uses an implicit solution for the vertical and local components and explicit time-stepping solution for the horizontal advection component of the energy conservation equation:

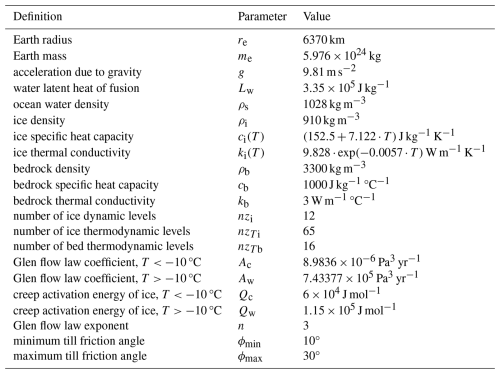

where V(r) is the 3D ice velocity and coefficient values are listed in Table 4. Heat source terms include full SSA and SIA contributions to deformation work (Qd) and the boundary heat flux from basal sliding (τb⋅ub). The coefficients with the i subscript denote ice: density (ρi), heat capacity (ci), and thermal conductivity (ki).

Horizontal advection is discretized using a second-order consistent 3 point upwinding scheme. Vertical diffusion and advection is solved implicitly using the power-law finite volume treatment of Patankar (1980). Interface diffusivities are based on geometric means as per ibid.

The discretization of the energy conservation equation for the basal ice grid cell is non-standard to enable a solution of the temperature at the basal interface as needed for accurately determining thermal activation of basal sliding. To do so, horizontal advection and the time derivative in Eq. (15) use a basal grid-cell centre temperature that is computed via linear interpolation between the basal interface temperature and cell centre temperature of the vertically adjacent ice grid cell. On the other hand, solution of the basal interface temperature means that no interpolation is required for vertical diffusion and advection.

For thin ice (H<50 m), basal temperature is set to that of the highest elevation neighbouring grid cell with ice thickness >50 m, and ice temperature is linearly interpolated in the vertical from the bed to surface. If there is no appropriate neighbour, the whole ice column is set to mean annual surface temperature. For floating ice, the basal temperature is set to the pressure melting point.

Unlike many older generation ice sheet models, energy is conserved when a grid-cell reaches the pressure-melting point. This is accomplished via an extra iteration within the tri-diagonal solution of the implicit energy conservation solution. The residual heat is then used for basal melt except for floating marine conditions for which a submarine melt and refreezing model is active (Sect. 2.7.2). The vertical implicit solution is over the whole ice and bed grid. Thermodynamic time-stepping is subject to horizontal CFL constraints using time-interpolated horizontal ice velocities. Though the vertical solution is implicit, this does not mean that the solution will have no time-step sensitivity. As such, the solver includes a vertical sub-iteration to restrict the time-step for any single vertical column to a set factor of the CFL stability threshold. This sub-iteration time-step factor has a default value of 10 (chosen on the basis of sensitivity tests) but is adjusted as needed to impose a maximum of 100 sub-iteration time-steps.

Given the grid cell dimensions for large ice sheet glacial cycle contexts (and generally much lower horizontal temperature gradients relative to vertical temperature gradients), the default bed thermodynamics configuration assumes vertical diffusive heat transport only (as supported by a straight-forward scale analysis). A near unique feature of the GSM is that the bed thermal model accounts for permafrost via a standard heat capacity approximation (Osterkamp, 1987; Williams and Smith, 1989; Mottaghy and Rath, 2006). It also applies temperature forcing corrections at the top of subaerial frozen ground to partly account for the effects of seasonal snow cover and surface vegetation (Smith and Riseborough, 2002). The GSM thermal bed has a default depth (GSM parameter BEDTdepth) of 4 km for which the lower flux boundary condition is specified by an input map (Sect. 2.17).

The GSM has the option (-DthreeDbedTdiffusion) of added explicit time-stepping horizontal heat diffusion in the bed. This would be more appropriate for grid resolutions of 10 km or finer or for regions where there are large horizontal gradients in the input deep geothermal heat flux field. However, the available reconstructions for this boundary condition are somewhat vague as to the exact depth they represent, often self-described as being near the bed surface. These reconstructions will already embody horizontal heat diffusion up to their representative depth. If this depth is above the chosen (default 4 km) depth of the bed thermal model, activation of GSM horizontal heat diffusion would effectively result in erroneous doubling of horizontal heat diffusion over the depth of overlap.

The activation of horizontal diffusion is computationally inexpensive (about a 2 % increase in run time). For a coarse 40 km grid resolution Antarctic two glacial cycle simulation, its addition can alter root-mean-square-error discrepancies with present day input ice topography and observed marginal ice velocities by approximately 10 m and 45 m yr−1 respectively.

A comparison of results for an older (SIA only) version of the GSM (but with the same bed thermal model) against North American deep borehole temperature profiles along with a full description of the bed thermal model are in Tarasov and Peltier (2007).

The default coupling between GSM ice dynamics and thermodynamics is explicit with a minimum one year time-step. However, the GSM includes an option for an iterative implicit coupling solution (-DimplicCoupleDynTherm). The implicit coupling iteration is for each ice dynamical time-step. It is subject to a chosen convergence threshold for both maximum ice thickness and horizontal velocity component differences between successive iterations.

2.7 Mass balance processes

Mass balance process representation was chosen based on space-time resolution of required inputs and associated uncertainties.

2.7.1 Positive degree day and positive temperature insolation surface melt (PDDsw) and refreezing

The GSM uses a novel extension of the classical positive degree day (PDD) scheme that accounts for the changing short wave (SW) component of the surface energy-balance. PDDs for any day are herein defined as the hourly time average of the maximum of 0 and the near surface air temperature (in degrees Celsius). PDD schemes (e.g., Cuffey and Paterson, 2010) traditionally use two constant melt coefficients to account for the changing albedo between ice and snow. However, it is well known that ice and snow albedos continuously vary. Furthermore, experiments with full surface energy balance models have made clear that orbital changes in short-wave forcing significantly affect surface mass-balance (van de Berg et al., 2011). From a physical point of view, PDD's are effectively a way to account for the long-wave, latent heat, and sensible heat flux components of surface energy balance (as all these fluxes depend on air temperature), but they do not account for variations in net short-wave fluxes beyond the binary choice of snow and ice PDD melt coefficients.

Observationally, fitted PDD melt coefficients vary over a wide range (both spatially and seasonally, e.g., Braithwaite, 1995; Hock, 2003). We ascribe these variations in large part to changing mean net SW inputs and therefore choose a near lowest observationally-inferred value 3.3 mm/PDD (ice equivalent) for a single PDD coefficient (e.g., Braithwaite, 1995; Hock, 2003) to capture the non-SW energy flux components. This value is a bit larger than that which would be inferred on the basis of pure long-wave and sensible energy balance to account for latent heat contributions.

For the shortwave component, a key challenge is that the short-wave input only contributes to surface melt if the surface temperature is at 0 °C. This constraint is often accounted for in present-day contexts for which hourly temperature and surface energy flux observations from automatic weather stations are available (e.g., Irvine-Fynn et al., 2014). However, for paleo ice sheet modelling contexts, typically only monthly mean temperature climatologies are available. As such, short of the few coupled ice sheet and climate models able to do full energy balance calculations (e.g., Krapp et al., 2017; Willeit et al., 2022), this constraint has not been applied in paleo ice sheet modelling contexts.

A possible computationally efficient solution to imposing this constraint arises from the similarity of the above temperature threshold to that of the contribution of PDDs to surface melt. Just as PDDs are computed for paleo modelling contexts based on a probabilistic distribution around mean monthly temperatures (e.g., Tarasov and Peltier, 1997a; Wake and Marshall, 2015), a positive temperature time integrated surface insolation flux may also be computed. This requires an assumption relating near surface air temperature to actual snow/ice surface temperature. Though not identical we assume that on a time integrated basis, errors resulting from imposing the 0 °C constraint on air temperature (as opposed to surface temperature) are relatively minor compared to other sources of error. The GSM uses a statistical model for the shortwave insolation for 2 m air temperature above 0 °C (Swrm) as a function of mean monthly: solar insolation, number of PDDs per day (PDDd), and standard deviation of air temperature . The model was derived from regression of mid to high latitude 4 hourly insolation and 2 m air temperatures from the PLASIM GCM (Fraedrich, 2012) over a deglacial transient run (Andres and Tarasov, 2019) and takes the form:

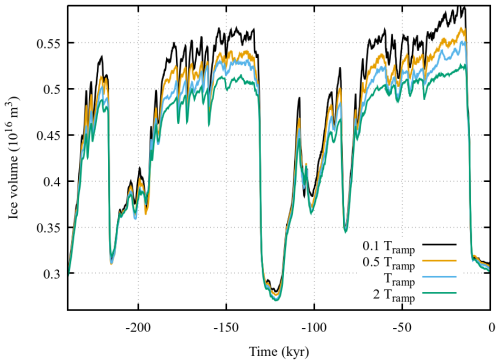

This regression captures much of the source GCM data signal (Fig. 3) with residual differences likely dominated by the lack of accounting for variations in cloud cover. The GSM surface insolation solution also accounts for orbital dependence and atmospheric transmissivity dependence on mean monthly solar angle (using the formulation of Irvine-Fynn et al., 2014).

Figure 3Comparison of GCM computed and regressed function used in GSM for monthly mean of positive degree daily surface insolation. Results are disaggregated for snow and ice surfaces with ensemble parameter CRadSMB in Eq. (16) set to its nominally regressed value of 0.345.

To partially address the sensitivity to unresolved cloud cover, a cloud radiative transmissivity factor (GSM parameter CloudFactor) enables ice sheet scale adjustments. This factor is currently set to 0.7 with one exception. Based on initial ensemble modelling and motivated by the high observed frequency of thick cloud cover, the factor for Iceland is set to 0.4. The CRadSMB ensemble parameter (Eq. 16) also provides an ice sheet scale ensemble parameter to partly address remaining uncertainties.

Snow surface albedo (using the recommended -DalbT2m compile flag) is a continuous function (Gabbi et al., 2014) of the nominal daily maximum 2 m air temperature (T2max). This is approximated as a function of mean monthly 2 m air temperature () and standard deviation () thereof:

Ice surface coalbedo (1−albedo) is 2.8 times snow surface coalbedo. Firn albedo is set to the average of the snow and ice albedos.

To date, it has been common for paleo ice sheet models to determine PDDs as a function of mean monthly temperature assuming a Gaussian distribution with constant standard deviation (e.g., Tarasov and Peltier, 1997a; Albrecht et al., 2020b). However, an examination of hourly temperature data from Greenland stations indicates this to be quite inaccurate (Wake and Marshall, 2015). As such, for computing PDDs, the GSM uses an observationally-fitted non-Gaussian distribution as a function of mean monthly temperature that was tested for various sites across Greenland, Norway, and Antarctica (Wake and Marshall, 2015). This distribution has skewness and kurtosis with linear dependence on mean monthly temperature, and quadratic dependence for the standard deviation. When coupled to full climate models, the GSM can instead take the monthly grid-cell standard deviation from the climate model.

The GSM surface melt model contrasts with insolation-temperature melt models (e.g., Robinson and Goelzer, 2014) implemented with the assumption that snow melt is a linear function of daily mean temperatures and that explicitly ignore the fraction of daily insolation required to bring the ice surface temperature to the melting point. The arguably largest sources of uncertainty for any paleo surface melt model will be errors in accounting for variations in hourly temperature, atmospheric transmissivity (especially due to cloud cover), and surface albedo.

The GSM uses a surface meltwater refreezing scheme that approximately accounts for firn meltwater retention and available refreezing potential. In detail, the model sets the thickness of annual superimposed (refrozen) ice (supice, with allowance for repeated melt/refreeze in a year) to

where NDY is the mean number of negative degree years computed in a similar approach to PDDs (or equivalent to ). The maximum thermodynamically active depth dFRZ is set to 3.675 m (ice equivalent) based on loose tuning to present-day RACMO2.3p2 results for Greenland (Noël et al., 2018) and respecting bounds in Reijmer et al. (2012). The first term in Eq. (20) sets the available freezing potential (as per Huybrechts and de Wolde, 1999), the second term is the available supply of water for refreezing, and the third term the available pore space for trapping meltwater (set to the maximum modelled value for present-day Greenland for both RACMO2 and MAR Regional Climate Models (RCM) in Reijmer et al., 2012). This parameterization was chosen based on the near best fits after retuning of the Huybrechts and de Wolde (1999) approach in Reijmer et al. (2012) with the added pore trapping condition based on the results shown in this refreezing model comparison. The slight retuning of dFRZ from the value in Reijmer et al. (2012) was necessitated by the use of the more physical NDY factor as opposed to the mean annual temperature used by Huybrechts and de Wolde (1999). Given the tuning against Greenland RCM modelling, the applicability of this scheme and its current parameters to other ice sheets is unclear. It is likely reasonably applicable for other similar maritime proximal ice sheet ablation zones on the basis of climatic similarity. As such, RCM modelling of continental ablation zones would be a priority for testing/refinement of this scheme. Unfrozen meltwater will also be retained in any ice surface grid-cell scale depressions when the surface hydrology solver is active in the GSM.

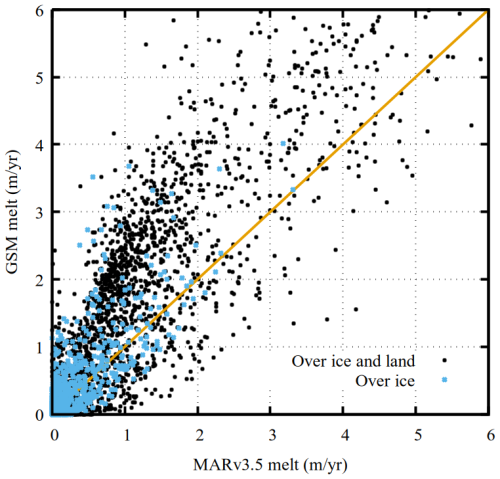

For further partial validation, the combined GSM melt and refreezing scheme (with corresponding default ensemble parameter value CRadSMB=0.33 in Eq. 16) is relatively unbiased over ice in comparison to the results of a regional climate model (MARv3.5.2, Fettweis et al., 2017) for the GRIS (cf. Fig. 4). The GSM has an overall positive bias for melt over all surfaces for larger values (>1 m yr−1) compared to that of the climate model. It is unclear to what extent this discrepancy as well as the scatter in Eq. (16) is attributable to the previously discussed sources of uncertainty that would also apply to all climate models, especially the hard to accurately predict cloud cover.

Figure 4Comparison of net melt (total melt – refreezing) between the GSM and the results of 20 km resolution regional climate modelling (1879:1999 mean climatology, MARv3.5.2, Fettweis et al., 2017) for the present-day GRIS. The GSM used the mean monthly precipitation and 2 m temperature climatologies from the latter.

The determination of monthly mean rain/snow fraction uses the monthly mean positive degree fraction for near surface air temperature. To better reflect that this fraction tends to be physically determined well above the surface, this fraction is computed relative to PDCUT=2 °C. However, if there is evidence for a prevalence of temperature inversions during precipitation, this reference value should be lowered.

To partially account for the reduced variance of hourly temperature during cloudy days, a Gaussian distribution with a reduced effective standard deviation (σPDf, as compared to that of Wake and Marshall, 2015, used for the PDD determination) is used for the positive degree fraction. We use the observational fitted value of Seguinot and Rogozhina (2014):

Though precipitation, surface melt, PDDs, positive temperature insolation, and NDYs are computed monthly, surface meltwater refreezing is computed yearly. Furthermore, all net snow accumulation (i.e. after melt loss) in one year transitions to ice the next year. This invokes the assumption that once surface mass balance is positive in the yearly cycle (on a monthly mean basis), refreezing won't be significant until the start of the next melt season. This avoids issues around tracking snow age and snow amounts between consecutive years at the cost of errors that are overwhelmed by input and parametric uncertainties. For those doing detailed firn modelling, a more refined (likely sub-diurnal) approach would be required.

2.7.2 Submarine melt and refreezing

Though there has been significant progress in submarine melt and refreezing parameterizations (as compared in Asay-Davis et al., 2017; Favier et al., 2019), a confident and computationally tractable representation for submarine melt remains an ongoing challenge. This is especially so for glacial cycle contexts for which the required ocean temperature fields are unlikely to be available to the requisite accuracy in the foreseeable future.

The recommended sub ice shelf melt (SSM) representation for the GSM is the (-DSSMslope -DSSMslopeLJGW19) buoyant plume model from Lazeroms et al. (2019). It give the SSM (ssm in m yr−1)) as a function of the basal ice angle (θ), ambient ocean temperature near the grounding line (Ta), local ice depth (zb) and a non-dimensional horizontal coordinate x:

This plume model also accounts for refreezing via negative SSM values. The depth of the plume source grounding line (zgl) and associated location and depth for extraction of Ta is determined via a downslope search. The reference freezing temperature (Tfz) at the grounding line is depth corrected. There is the option of subjecting Tfz to regional or whole grid ice shelf ensemble parameter dependence (CTssmCut) to partly compensate for limitations in the ocean temperature forcing:

A related limitation is that the plume model is purely buoyancy driven and therefore ignores horizontal advection due to sub ice shelf ocean circulation. The overall SSM ensemble parameter CSSM adds further parametric degrees of freedom to partly compensate for these error sources.

There are two options for subshelf melt at grounding line grid cells. The default (no special compile flag) option is that the GSM only applies the above subshelf melt parameterization to fully floating grid cells. This is in accordance with resolution convergence tests comparing application of submarine melt only to floating grid cells as well as to fractional inclusion of grid cells crossing the grounding line grid cells in proportion to the subgrid grounded ice fraction (Seroussi and Morlighem, 2018). However Seroussi and Morlighem (2018) only tested subshelf melt parameterizations that do not decrease in magnitude near the grounding line (before application of subgrid relative floating area scaling), unlike that of the recommended Lazeroms et al. (2019) plume parameterization. Furthermore, the experiments only evaluated a 100 year retreat scenario and it remains unclear whether their conclusions hold in the case of a glacial advance and subsequent retreat scenario of more relevance for glacial cycle modelling. As such, the GSM has an option for scaling of subshelf melt by the relative subgrid area that has floating ice (-DGLssm, similar to configuration SEM1 in Seroussi and Morlighem, 2018). This has an added scaling parameter (RfactGLssm) to further reduce grounding line grid cell subshelf melt. Sensitivity tests have found grounding retreat and advance to be more stable for RfactGLssm =0.5 compared to the simulations with subshelf melt only for fully floating grid cells.

Calving face submarine melt is taken from the results of high resolution Massachusetts Institute of Technology general circulation ocean modelling (Rignot et al., 2016). We use their extracted analytical fit for submarine melt of west Greenland outlet glaciers. This has a dependence on the approximated upstream meltwater velocity (q, m d−1) and the interpolated (or extrapolated) ocean temperature (). In detail, the submarine melt (qm in m d−1) of a calving face that extends to depth d is given by:

with a=0.39, m−a da−1 °C−β , and β=1.18 as per Rignot et al. (2016). The freezing point (CTssmCut) is treated as an ensemble parameter to impose bias corrections for the ocean temperature forcing (as used for sub ice shelf melt described above). B=0.15 °C−β m d−1 as per Rignot et al. (2016). The above equation is rescaled for m yr−1 quantities and q is approximated by scaling the sum of twice the subglacial melt rate of the grid cell (to allow for some upstream contribution) and surface runoff by the grid cell area to marine face area ratio. An extra factor of 0.5 is also inserted in this rescaling to partially compensate for the impact of using annual mean inputs, given that intra-annual variations are largely driven by changes in q (annual averaging will increase the effective value of qa given that ). The application of eq. 24 in the GSM introduces uncertainties arising from the coarser grid scale resolution typical of paleo ice sheet modelling as well as limitations in the required inputs and their averaging to annual means. As such, an ensemble scaling parameter (Cface) is added. Until recently this has only been applied to the B coefficient (i.e. as in Eq. 24). However, given the potentially large uncertainties due to submarine circulation (driven in large part by buoyancy forcing from meltwater), the GSM has the option of making the A coefficient the ensemble parameter (and thus in Eq. (24), with the -DCfaceMltFW compile flag).

2.7.3 Marine ice shelf calving

For marine floating ice calving, two dynamical controls are assumed. First, a stress-balance crevasse propagation parameterization following Pollard et al. (2015) is used. This is expressed as a horizontal wastage rate (Wc) (though numerically applied as an appropriately scaled contribution to the surface mass-balance forcing) subject to ensemble parameter Ccalv:

where each d? term represents a contribution to crack depth propagation as detailed below. As indicated in Eq. (26), calving is activated when the relative total crevasse depth (r) reaches the critical relative depth rc, with latter set to the value in Pollard et al. (2015). As calving in the GSM is only allowed for ice marginal grid cells, the sum of the contributions from strain rate divergence to dry-surface (ds) and basal (db) crevasses is given by that for a free floating unconfined ice face (e.g., Schoof, 2007):

Following Pollard et al. (2015), an accumulated strain contribution is included to crudely account for upstream accumulation of fine-scale fracturing from strain divergence:

As detailed in Pollard et al. (2015), this derives from a steady flow solution to the time integral of the ice divergence along the flowlines. To improve GSM fits to present day (PD) observed Antarctic ice shelf extents, the 1600 m yr−1 value for the denominator (representing the flowline velocity at the beginning of the ice shelf trajectory) in Pollard et al. (2015) was reduced by a factor of 2.

The dt term is added to prevent floating ice thinner than ∼150 m in accord with present-day Antarctic ice shelves. Our implementation has slight alterations to that imposed in Pollard et al. (2015) to better facilitate ice margin expansion. These are the use of the maximum of adjacent grid cell ice thickness (Hadjmx) instead of the marginal ice thickness (Ht) and an increase of the cessation threshold to 200 m from 150 m:

Recovery of present-day AIS ice shelf extent is also further improved with imposition of a minimum marine depth of 300 m for activation of this component.

The remaining dw term in Eq. (26) is the additional surface crevasse depth due to hydro-fracturing from water infill:

This matches the corresponding term in Pollard et al. (2015) for ChydCrk=1 as motivated in that paper.

The default terminal ice thickness (Ht) estimate in the GSM is simply max(0.95 H,200 m) with the floor value set in line with what is mostly observed for the margins of large Antarctic ice shelves. The code includes (as a compile flag -DhedgeActive) the downstream thinning option of Pollard et al. (2015). The activation of this option tends to increase numerical instability with otherwise limited impact on results after accounting for compensation from ensemble parameter variations.

Unlike many other ice sheet models, a second control is the assumption that if summer sea surface temperature forcing (approximated by 2 m air temperature) is too cold to permit sea-ice free conditions (summer T2 m< TcalvCut °C), then iceberg production will cease due to back-stress and potentially reduced adjacent marine convection (driving undercutting). This is motivated by both the tendency for seasonal calving in the high Canadian Arctic to initially occur after the loss of land-fast sea ice and the bracketing of the Antarctic ice shelf margin with the −2 and −6 °C mean summer sea surface isotherms. The one exception is that complete calving is assumed for ice shelves beyond the continental shelf break. This shelf break location is set by present-day depth equal to GSM parameter rDepthDeepCalv (Ice sheet Index) =860 m, except for Antarctica where a 1700 m depth was found necessary to permit present-day fringing ice shelf margins around the Antarctic Peninsula as observed. This deep sea calving reduces computational cost where an ice shelf would definitely have no confinement and therefore impose no back-stress upstream.

Ice calving is computed for each marine ice margin grid cell interface, even if this entails more than one interface of a grid cell. Given the limited grid resolution, an ice covered grid cell is taken as marine margin if it has an adjacent grid cell with ocean depth greater than 40 m and ice cover less than 5 m thick. The GSM tracks open marine basin connectivity to the ocean and shuts down calving when the connectivity is lost on the assumption that iceberg congestion will adequately increase back-stress on the calving front to terminate calving.

2.7.4 Tidewater calving

We use the ice cliff failure enabled tidewater calving scheme of Pollard et al. (2015), with the horizontal calving rate (Wct in m yr−1) computed as:

where

The critical surface height above the water line for ice cliff failure is set to Hc=100 m. HGL is ice thickness at the grounding line (computed from applying the flotation condition to the horizontally interpolated grounding line depth). hsw= is height above water at the grounding line, and the contribution from crevasse water depth (dw) is computed as above for ice shelf calving. θ is related to the back stress on an ice shelf with value 1 for an unbuttressed ice shelf or no floating ice at all. As we restrict calving to the ice marginal grid-cell, the model has a default option of permanently setting θ to this value. This restriction is distinct from that of Pollard et al. (2015) which allows marine ice cliff failure for interior (non-marginal) ice at the grounding line if there is no significant buttressing by the attached ice shelf.

2.7.5 Lake calving

As lake margins of ice sheets are indicative of relatively warm conditions, the GSM lacustrine calving model assumes that surface melt filling of cracks and associated crack propagation is not a control on lake calving. Instead, it is assumed that the main control is the available heat to melt icebergs. Once all excess heat is used up, the lake is assumed to quickly choke up with icebergs, and thereby block further calving. As such, lacustrine calving is simply implemented as extra melt applied to the grid cell covering the calving margin.

Given the large process uncertainties, the potential iceberg melt is just set to the total computed net potential surface melt of adjacent lake filled grid cells times a GSM parameter (flac). This thereby lacks accounting for extra lake grid cells that are not in contact with the ice-sheet. It also assumes that the effective surface albedo of the lake will be dominated by that of icebergs and ice melange, and thus the melt potential for a unit area is close to that computed (the surface melt calculation doesn't have a separate albedo for lake cover).

Two further somewhat adhoc conditions are imposed to ensure there is sufficient exposure of the grid cell ice to adjacent cell water and sufficient lake depth to enable heat circulation. These requirements are: (1) local water depth of calving grid cell is more than the lesser of SLACMX (set to 50 m) and the local ice thickness, and (2) ice-free adjacent cell water depth is greater than SLACMIN (set to 20 m except for EA = 33 m to enable adequate EA ice sheet expansion in certain regions).

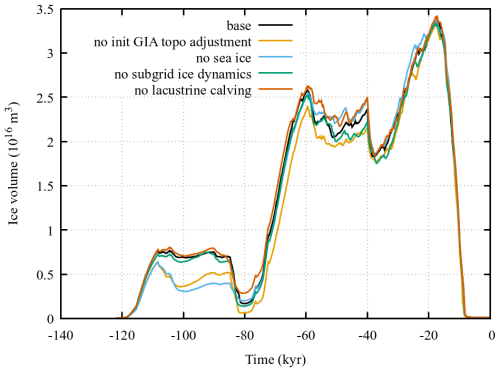

For an example North American ice sheet (NAIS) simulation, inhibition of lacustrine calving (cf. Fig. 5) has a significant impact on ice sheet volume during the 80 ka interstadial and 60 to 40 ka glacial interval.

2.8 Surface drainage solver

The mass-conserving surface drainage solver simply diagnostically routes water downslope, filling depressions (lakes), until an ocean depth of 200 m or until no water is left. It computes marine drainage summaries for defined drainage basins, for total (including precipitation over ice-free land), ice sourced, and solid-fraction only drainage. For present-day ice free surface topography, the solver uses a modified version of the USGS EROS HYDRO1k hydrologically self-consistent DEM (USGS, 2004). The drainage preserving upscaling of the DEM includes some by hand corrections to capture the controlling sill elevation for the southern drainage of the central LIS (e.g., pro-glacial lake Agassiz). This topography is then dynamically evolved for ice cover and GIA. Details on the solver, drainage topography creation, and validation are in Tarasov and Peltier (2006).

The algorithm is run every dlong years (default is 100 year) and accumulates mean surface runoff and marine ice discharge over the dlong interval. A discharge map is also created for coupling with climate models or other such contexts.

Given the limited subaerial Greenland and Antarctic terrestrial surfaces over which grid-cell scale pro-glacial lakes could form, the surface drainage solver is generally not activated for these ice sheets.

2.9 Sea and lake ice formation

The GSM includes a simple thermodynamic sea and lake ice formation module. The inclusion of the former is motivated by evidence for paleocrystic ice (floating ice grown directly from local precipitation and not terrestrially sourced, Bradley and England, 2008). It was also found necessary to remove spurious ice holes in the Barents and Kara Seas that occasionally developed under glacial moisture starved conditions. As shown in Fig. 5, sea ice inclusion can play a significant role in increasing NAIS glacial inception ice volume, a long standing challenge for paleo ice sheet models when coupled to full climate models.

The lake and sea ice basal accumulation model assumes a monthly approximately thermodynamic steady state for the floating ice, and thereby a linear temperature profile. After a trivial integration this gives growth in effective sea or lake ice thickness (Hf) over time Δt as:

where Lw is the latent heat of fusion for water, k is the thermal conductivity of ice, and

The change in ice thickness is not directly imposed in the GSM but instead converted to an effective contribution to the surface mass-balance term (otherwise this ice accumulation would break mass conservation in the surface runoff discharge calculation). This lake and sea ice remains subject to all the other mass-balance processes in the GSM.

2.10 Climate forcing

The GSM climate forcing generates evolving monthly precipitation, near surface air temperature, and ocean temperature fields. It includes dependence on various glacial indices as detailed below.

2.10.1 Glacial indices for climate forcing

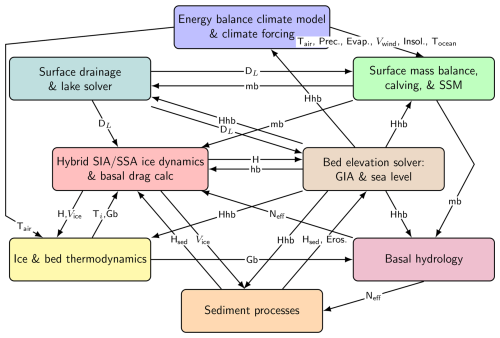

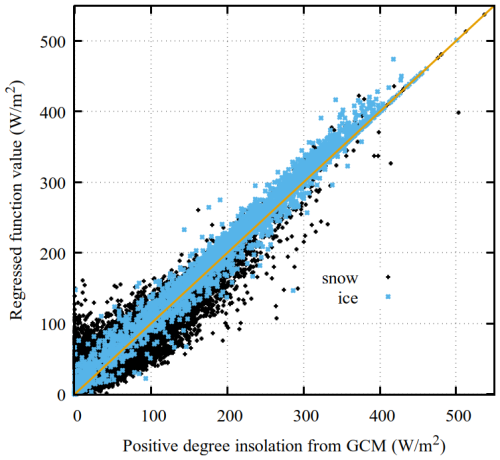

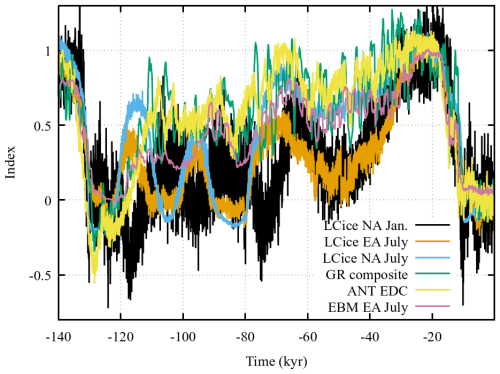

The GSM has various time and/or state evolving indices for driving components of the climate forcing (Fig. 6). The indices cover a range from below 0 to beyond 1 with 0 representing the 0 ka (nominally 2000 CE) state and 1 the LGM state. A to date unique feature is the addition of monthly dependence for the glacial indices (Fig. 6). The traditional reliance on mean annual glacial indices (e.g., Marshall et al., 2000; Scherrenberg et al., 2023) hides the significant impact of changes in seasonality over the glacial cycle. For example August − February differences range up to 0.30 over the last two glacial cycles for the EBM derived monthly glacial index described below. For a more advanced coupled ice-climate model over the last two glacial cycles, the glacial index differences can exceed 1.0 (Geng et al., 2025). Furthermore, mean annual glacial indices result in excessive summertime variability as these records average the relatively low climatological summer time variance of air temperature with the much higher variance of winter temperatures (Fig. 6 and Geng et al., 2025).

Figure 6Comparison of some GSM glacial index input options. The “EBM EA July” entry is the computed EBM glacial (Ie) index for a sample Eurasian GSM simulation. The LCice indices are derived from the same coupled GSM-LOVECLIM simulation (Geng et al., 2025). The GR composite and ANT EDC (Epica Dome C) indices are derived from ice core records (cf. Table 6).

The Ie index is the mean monthly EBM temperature anomaly relative to present-day over the 40N:80N latitudinal band divided by corresponding LGM anomaly. The Ig glacial index uses ensemble parameter rWtEBMindx to weigh Ie with an input glacial index chronology specified in the runscript. The latter glacial index can be in mean annual format from a deep ice core isotopic record. There is also a compile flag option to include a monthly glacial index input from a more advanced coupled ice and climate model.

For computing 2 m air temperature, the glacial Ig is subject to two ensemble parameters, CIT and ΘT, respectively adjusting amplitude and phase:

For controlling the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation impact parameterization (cf. next subsection), the annual IN index uses the average of the scaled pCO2 forcing () and a North Atlantic index for the scaled mean annual EBM temperature anomaly over 40 to 20° W and 40 to 45° N region. IN ranges from about −5 to 0.

The Id ice dome index is a function of the maximum elevation of the main ice dome (hIdmx). It is subject to ensemble parameter hIdes as following

The index is used to partly account for possible large scale circulation response to the changing elevation of the main ice dome as discussed below.

2.10.2 Surface climate forcing

The biggest source of uncertainty for glacial cycle ice sheet modelling is the climate forcing. To partly address this, the GSM features different climate forcing options that can be combined under ensemble parameter specified weighting.

Air temperature

The first temperature forcing option is an asynchronously coupled 2D energy balance climate model (EBM), running at spherical harmonic truncation T11 with non-linear sea ice and snow albedo feedbacks (Deblonde et al., 1992).

Sea level temperature (T) is computed by an approximation for the energy balance of the tropospheric and mixed-layer ocean column that only accounts for vertical radiative fluxes, horizontal diffusive heat transport, and a parameterized North Atlantic oceanic heat flux contribution (NAHF):

The equation is solved for monthly mean equilibrium solutions on default 100 year increments. Yearly (ty) and monthly (tm) dependence are explicitly indicated in this section (though at times subsumed into t). To avoid clutter, spatial (x,y or r) dependence is usually not shown. The linearized long-wave emission () accounts for reduced emission at higher elevations due to cooler temperatures and is implemented via a constant lapse rate (λebm). The absorbed short-wave radiation is set to the product of the solar constant So (1360 W m−2), an effective coalbedo a(r,t), and the solar distribution function with dependence on latitude θ. The coalbedo has latitudinal dependence derived from satellite observations (Stephens et al., 1981) and seasonal dependence on snow and sea ice cover. The time-dependent orbital parameters for S are computed as per Berger and Loutre (1991). The heat capacity C has four possible values according to surface type (land, land ice, sea ice, and water). The diffusion coefficient D is tuned to preserve the present-day observed mean latitudinal temperature gradient. The radiative forcing due to changing atmospheric greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations (currently restricted to CO2 and CH4) is accounted as per Myhre et al. (1998) (though with rounding up of the numerical coefficients to partly compensate for missing feedbacks in the EBM):

for CO2 and

for methane. The chosen reference concentration values are between those corresponding to pre-industrial and a 1980:2000 CE reference climate interval. This is to account for far from complete transient response to present-day GHG changes.

Given the impact of heat transport by the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation and its changes over the past, as well as to improve fits to present-day observed climate, the EBM has an added horizontal surface ocean heat flux (NAHF(r,ty)). This flux has geographically dispersed weak sinks, and a source concentrated around (17.5° E, 67.5° N), with the central position determined by root mean squared error minimization against present-day reanalysis climatology. This represents a displacement by about 15° E from the climatologically observed net ocean surface to air heat fluxes, presumably accounting for eastward advection by mid-latitude westerlies. The heat flux has various choices of dependencies on the current IN index value and the state history set by a compile flag. The current recommended choice is -DNAHFv3. It is also a function of pCO2 forcing and sea level, configured so as to induce Dansgaard-Oeschger-like oscillations in air temperature. Given the adhoc nature of the implementation, we leave the documentation to the source code (pGSM.F90) for those interested.

A linear version of the EBM (without seasonal snow/ice albedo feedback) has previously been evaluated against observations and output from an early version of the NCAR CCM (Community Climate Model) general circulation climate model (run at wave number 15 rhomboidal truncation). It was found to capture much of the millennial scale response on this spatial scale especially for the Northern Hemisphere (Hyde et al., 1989). Given that the EBM lacks atmospheric dynamics and as such won't be able to capture the effects thereof, the model is generally run in anomaly mode, with the EBM providing the climate forcing anomaly relative to a present-day monthly climatology (Trean) and subject to an ensemble scaling parameter CEBM:

This presumes radiative perturbations dominate the climate system response to orbital forcing changes.

Comparison of PMIP II and III simulations along with a dedicated set of CESM 1.2 experiments (Bakker et al., 2020) has identified Siberia as the region having the highest LGM summer temperature sensitivity to climate model choice and configuration. Lofverstrom and Liakka (2018) have also shown strong grid resolution dependence for Northern Eurasian June/July/August (JJA) surface temperatures for the NCAR CAM3 atmospheric GCM when run below T85. Given the low T11 resolution of the EBM and its lack of atmospheric dynamics, an added parameterization is used to correct excessive glacial summertime cooling as evidenced by Siberian ice growth in simulations contrary to the geological record. The additive correction field is approximately derived from differences between EBM and mean PMIP LGM JJA sea-level temperatures. On the assumption that relevant circulation changes are driven by topographic changes, this warming is scaled by product of the Fennoscandian ice dome elevation index Id and the GSM ensemble parameter rSumPlusEBM.

When run in single ice sheet mode, the EBM will underpredict glacial cooling as a result of the missing radiative impact of ice sheets that are not modelled. As such, the GSM has an option (-DdRadIndx) to implement a scalar decrease in shortwave input to compensate for missing ice sheets. Concretely, this is implemented as

with parameter dradSea set in the run script (generally ranging from 1 to 7 W m−2, determined by comparison of EBM results with single and global ice sheet configurations). This implementation assumes a −125 m mean glacial maximum sea level so that dradSea is the corresponding radiative forcing. The exponent value was chosen to approximately account for the limited radiative impact of the major Northern hemispheric ice sheets until their southern extent reaches regions not typically covered by snow or sea ice for the majority of the year. The exponent value will at some point be refined by modelling experiments with the EBM.

The second temperature forcing option is a glacial climate indexed (Ic) interpolation between a present-day reanalysis climatology and a full-glacial (LGM) climatology for mean monthly sea level temperature:

The glacial climatology ( and ) is derived from the highest resolution three to four climate model simulations in past PMIP experiments. It is the sum of the mean of the simulations and the top one to three inter-model Empirical Orthogonal Functions (EOFs, a mathematical tool to capture orthogonal modes of maximum variance). The addition of each EOF component for precipitation and two meter air temperature is subject to individual ensemble parameter weighting (CPEOF(i) and CTEOF(i)) to account for the significant inter-model differences in the PMIP simulations.