the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

VaPOrS v1.0.1: an automated model for functional group detection and property prediction of organic compounds via SMILES notation

Mojtaba Bezaatpour

Miikka Dal Maso

Volatile organic compounds play a significant role in atmospheric chemistry, influencing air quality and climate change. Accurate prediction of their physical properties is essential for understanding their behavior. This paper introduces VaPOrS (Vapor Pressure in Organics via SMILES) as a comprehensive tool designed to process SMILES notation of organic compounds, identify key functional groups, and apply group-contribution methods for property estimation. The core innovation of VaPOrS lies in its self-contained functional group recognition algorithm, which eliminates dependence on external cheminformatics libraries. The current approach enables fully auditable, easily modifiable, and computationally efficient detection of 30 functional groups required by the SIMPOL method. Compared to existing tools, VaPOrS avoids heavy SMILES-to-graph conversions and can obviate interface overhead, providing orders-of-magnitude speedups for large-scale atmospheric modeling scenarios. While this first implementation focuses on the SIMPOL method for estimating saturation vapor pressure and enthalpy of vaporization, the framework is readily extendable to other group-contribution schemes and thermodynamic properties (e.g., partition coefficients, volatility basis set models, solubility, Henry's law constants). The tool has been validated against manually counted functional groups and experimental saturation vapor pressure data for a diverse set of compounds. Results demonstrate excellent agreement with both the original SIMPOL model and experimental observations, while comparisons with existing tools highlight the robustness and accuracy of the new parsing functions. VaPOrS thus provides a generalizable and computationally efficient platform for property prediction of large molecular datasets, facilitating integration into chemical transport and climate models and streamlining the analysis of thousands of organic compounds in atmospheric science applications.

- Article

(4937 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are a diverse group of organic chemicals that significantly impact atmospheric chemistry. Their volatility allows them to easily enter the atmosphere, where they participate in complex chemical reactions that influence air quality, climate, and human health (Mellouki et al., 2015). VOCs are key precursors to both ground-level ozone and secondary organic aerosols (SOA). Ground-level ozone, a harmful air pollutant, forms through the photochemical reactions of VOCs with nitrogen oxides (NOx) in the presence of sunlight (Atkinson, 2000). Ozone is a major component of urban smog and poses serious health risks, including respiratory problems and cardiovascular disease (WHO, 2006). Secondary organic aerosols, on the other hand, result from the oxidation of VOCs, leading to the formation of particulate matter that can scatter sunlight and affect the Earth's radiative balance (Jimenez et al., 2009). These particles contribute to atmospheric haze, impact visibility, and have been linked to adverse health effects, including lung and heart diseases. Understanding the formation, transformation, and fate of VOCs is thus crucial for predicting their impact on both air quality and climate.

VOCs originate from a variety of sources, both natural and anthropogenic. Natural sources include biogenic emissions from vegetation, such as isoprene and monoterpenes, which are released in large quantities, especially in forested areas (Guenther et al., 1995). Anthropogenic sources are primarily related to industrial activities, transportation, fuel combustion, and the use of solvents and consumer products (Goldstein and Galbally, 2007; McDonald et al., 2018). The structural diversity of VOCs poses a challenge for their classification and analysis. They can range from simple hydrocarbons like methane to complex multifunctional molecules containing oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, and, for example, halogens. This diversity affects their physical properties, reactivity, and environmental behavior, making it necessary to study their properties comprehensively.

The physical properties of VOCs, particularly saturation vapor pressure and enthalpy of vaporization, play a critical role in determining their volatility and phase behavior in the atmosphere. Saturation vapor pressure is a measure of a substance's tendency to evaporate, and it directly influences the distribution of VOCs between the gas and particulate phases (Mattila et al., 1997). Compounds with high saturation vapor pressure are more likely to remain in the gas phase, whereas those with lower saturation vapor pressure can condense onto particulate matter, contributing to SOA formation (Donahue et al., 2006). Enthalpy of vaporization, the energy required to convert a substance from liquid to vapor, is an important property that influences the temperature dependence of saturation vapor pressure. Accurate knowledge of these properties is essential for modeling VOC emissions, their transport, and their transformation in the atmosphere.

The oxidation of VOCs significantly changes their chemical properties. An extreme example is provided by autoxidation, a chain-like oxidation process that propagates by sequential additions of molecular oxygen and resulting peroxy radical rearrangement reactions, which infuses multiple oxygen molecules to the hydrocarbon backbone. This process plummets the saturation vapor pressures of the participating VOC and ultimately forms so-called Highly Oxygenated organic Molecules (HOMs as expressed by Bianchi et al., 2019; Crounse et al., 2013), crucial intermediates in the formation of SOA. HOM formation is a common property of VOCs and is thus initiated by all common oxidants capable of forming alkyl radicals, including hydroxyl radicals (OH), ozone (O3), and nitrate radicals (NO3) (Zhao et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2023; Rissanen et al., 2014; Berndt et al., 2016) as well as by direct UV photolysis. The resulting HOMs can rapidly condense onto existing particles or sometime even form new particles through nucleation processes, thus contributing to the formation and growth of SOA. The formation of HOMs is heavily influenced by the structure of the precursor VOCs (Ehn et al., 2014). Recent advancements in mass spectrometry and atmospheric simulation techniques have provided valuable insights into the chemical pathways leading to HOMs formation and their role in atmospheric chemistry (Iyer et al., 2023; Bianchi et al., 2019; Vereecken et al., 2018; Jenkin et al., 2019; Iyer et al., 2021). Understanding the volatility of VOCs, and especially HOMs, is therefore essential for improving models of SOA formation.

Traditionally, the determination of saturation vapor pressure and enthalpy of vaporization has relied on experimental methods, such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Epping and Koch, 2023). While these methods provide accurate measurements, they are time-consuming, expensive, and often impractical for large-scale studies involving thousands of compounds. Moreover, many of the condensable chemicals relevant to atmospheric SOA formation are challenging to measure because their parent molecules are unstable, have never been synthesized, or, importantly, cannot be synthesized due to their inherent instability. These limitations highlight the critical need for approximative methods to estimate the physical properties of these compounds, as direct measurements are often unfeasible.

Given the limitations of experimental approaches, there is an obvious need for computational tools that can predict these properties efficiently. Such tools can complement experimental methods by providing rapid estimates for a wide range of compounds, facilitating large-scale atmospheric modeling studies. Various computational methods have been developed to estimate the saturation vapor pressure of organic compounds, complementing or replacing traditional experimental approaches. Among these, predictive models like COSMO-RS (COnductor-like Screening MOdel for Real Solvents) use quantum chemistry calculations to estimate thermodynamic properties, including saturation vapor pressure. COSMO-RS simulates the solvent environment and molecular interactions, providing a theoretical basis for property estimation. However, its computational intensity can be a drawback for large-scale applications (Klamt, 1995; Eckert and Klamt, 2004; Klamt et al., 1998). On the other hand, group contribution methods estimate saturation vapor pressure based on the contribution of structural groups within a molecule. These methods leverage empirical correlations derived from extensive datasets but often lack precision for complex or highly functionalized molecules (Joback and Reid, 1987; Myrdal and Yalkowsky, 1997). The Nannoolal method is a computational approach used to estimate the boiling points and saturation vapor pressures of organic compounds based on their molecular structure. This method utilizes group contribution techniques, where the overall properties of a molecule are determined by summing the contributions of its individual structural groups, such as functional groups and bonding patterns (Nannoolal et al., 2008). The EVAPORATION method is a tool designed for estimating the saturation vapor pressure of organic molecules, accounting for contributions from the carbon skeleton, functional groups, and their interactions, and it adjusts for functionalized diacids with empirical modifications. It predicts the saturation vapor pressure of various compounds using only molecular structure as input, making it applicable to a wide range of molecules (Compernolle et al., 2011). The SIMPOL method, developed by Pankow and Asher (2008), is a widely used group contribution method that correlates the presence of specific functional groups in a molecule to its vapor pressure. By summing the contributions of individual functional groups, the method provides an estimate of the compound's vapor pressure. The SIMPOL method has been validated against experimental data and is recognized for its accuracy and applicability to a wide range of organic compounds. Importantly, since all these methods employ group contribution techniques, they could potentially be integrated into automated tools, enabling the efficient handling of large datasets and complex compounds with minimal manual effort.

Despite the usefulness of existing tools such as UManSysProp (Topping et al., 2016) for vapor pressure estimation, they show limitations in correctly identifying functional groups in a range of organic molecules (see Sect. 4.3). These shortcomings can lead to significant deviations in predicted vapor pressures, particularly for multifunctional species relevant to atmospheric oxidation and SOA formation. Our observations of such discrepancies provided the main motivation for this work. To address these deficiencies, we developed a Python-based computational framework named VaPOrS (Vapor Pressure in Organics via SMILES) to process SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) notation of VOCs, automatically identify functional groups, and apply group-contribution methods for property estimation.

The core innovation of VaPOrS lies in its self-contained SMILES parsing and group recognition algorithm, which eliminates reliance on external cheminformatics libraries such as OpenBabel. Instead of depending on SMARTS-based pattern matching, VaPOrS explicitly searches for all possible patterns of each functional group directly from the SMILES string, ensuring full control over the detection logic. This approach makes the tool both transparent and adaptable, enabling straightforward extension to new group definitions and methods without external dependencies. In its current version, VaPOrS implements the SIMPOL method by detecting 30 functional groups required for estimating pure-component (sub-cooled) liquid saturation vapor pressure and the corresponding enthalpy of vaporization, without accounting for Raoult's law effects. However, this is only the first demonstration of the framework: the same group recognition functions can be applied to other parameterization schemes (e.g., group additivity, volatility basis set (VBS) models, partition coefficients, Henry's law constants), making VaPOrS a general platform for group-contribution modeling rather than a tool restricted to vapor pressure prediction. Therefore, the development of VaPOrS addresses several challenges:

-

Automated and auditable functional group detection: eliminating manual identification, reducing error potential, and providing full transparency in detection logic.

-

Computational efficiency: by bypassing Pybel's SMILES-to-graph conversions, VaPOrS reduces overhead, enabling much faster execution for large-scale atmospheric simulations involving thousands of compounds across many steps and grid cells.

-

Scalability and flexibility: capable of processing thousands of SMILES strings within seconds, with design features that make it portable to high-performance computing (HPC) environments and easily translatable to compiled languages such as Fortran for integration into large-scale chemical transport and climate models.

The potential applications of VaPOrS extend well beyond SIMPOL. As an instance, Pichelstorfer et al. (2024) recently introduced the auto-APRAM-fw framework for predicting the molecular structures of highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOMs) generated during autoxidation, outputting results in SMILES notation. Integrating these HOMs into atmospheric models requires both functional group identification and vapor pressure estimation, a process that becomes resource-intensive if performed manually or through non-specialized methods. VaPOrS provides an automated and efficient solution to this challenge by detecting functional groups directly from the SMILES strings and applying parameterizations such as SIMPOL for vapor pressure. More generally, the framework can facilitate integration of large molecular datasets into existing atmospheric databases and simulation platforms, advancing the predictive capability of SOA formation models. Some of the key atmospheric databases and models that could benefit from this tool are discussed in the results and discussion section.

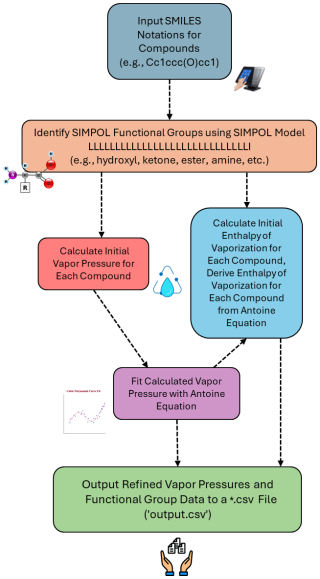

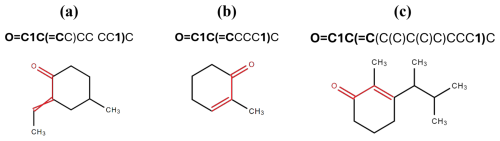

The developed VaPOrS begins by processing the SMILES notation of the target chemical compounds. SMILES strings are used as inputs to identify the molecular components most relevant to volatility predictions, such as number of carbon atoms, functional groups, and cyclic structures. Altogether 30 functional groups parameterized in the SIMPOL method are identified. Several functions are required to efficiently parse and interpret the structure of each compound. The model consists of two main parts. The first part is dedicated to identifying and counting the number of functional groups within the target while the second part focuses on calculating the saturation vapor pressure as a function of temperature and providing the corresponding Antoine equation parameters.

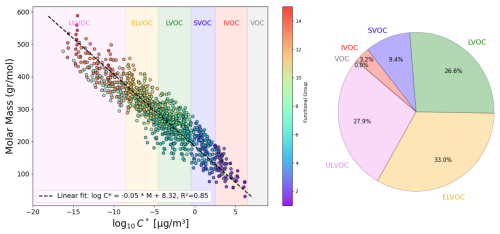

Figure 1Overview of chemical functional groups identified and analyzed by the VaPOrS, including number of (a) carbon atoms, (b) aromatic and (c) non-aromatic rings, (d) non-aromatic double bonds (C–C), (e) hydroxyl – alkyl (e1) and aromatic (e2) –, (f) hydroperoxide, (g) aldehyde, (h) carboxylic acid, (i) peroxy acid, (j) ketone, (k) ethers – open-chain (k1), alicyclic (k2), and aromatic (k3) –, (l) ester, (m) nitroester, (n) C=CC=O in non-aromatic rings, (o) nitrate, (p) nitro, (q) acylperoxynitrate, (r) peroxide, (s) nitrophenol, (t) amines – primary (t1), secondary (t2), tertiary (t3) , and aromatic (t4) –, and (u) amides – primary (u1), secondary (u2), and tertiary (u3).

2.1 Functional group identification

The first part of the model identifies and counts 30 distinct structural groups in organic compounds that are recognized by the SIMPOL method as influential on saturation vapor pressure. These groups include functional components like carbonyl groups (−C=O), hydroxyl groups (−OH), amines (−NR3), ethers (−R–O–R−), and several others (see Fig. 1). The model processes the SMILES string of each compound and applies functions to detect the presence and quantity of these groups. To achieve this, the SMILES string is parsed by several dedicated functions, each corresponding to a specific functional group (e.g., O-atom in a carbonyl or hydroxyl). The results are stored as variables that represent the number of occurrences of each group within the molecule. These counts are then used as input parameters in the saturation vapor pressure calculation. This identification process is critical, as the functional groups detected are the most impactful to the molecule's saturation vapor pressure. By systematically identifying the relevant groups for each compound, the model prepares the necessary data for the next phase of thermodynamic calculations. At the current stage, VaPOrS operates using canonical SMILES as input. This choice was made because canonical SMILES are the most common representation in chemical databases and provide a standardized representation of each molecule, which simplifies functional group detection and validation. Although alternative SMILES forms (e.g., kekulized or non-canonical variations) can represent the same molecule, these are not yet supported in the present version. To maintain consistency, users should therefore provide canonical SMILES when running VaPOrS. The following Sect. 2.1.1 to 2.1.19 provide detailed descriptions of the first steps of the model computations.

2.1.1 Carbon atoms

Carbon atoms are an essential component in all organic molecules, and their number forms the basis for the calculations of molecular properties utilizing group additivity. The carbon_number(s) function counts the occurrences of both uppercase (“C”, representing carbon atoms in alkyl chains) and lowercase (“c”, representing carbon atoms in aromatic rings) characters in the SMILES string. The total number of carbon atoms is then calculated by summing these occurrences.

2.1.2 Identification of branches and rings in SMILES

Since SMILES notation uses parentheses to denote branching in molecular structures, and numeric indicators to specify ring closure, the model incorporates specialized functions to handle these aspects.

-

The function

find_closing_parenthesis(s, open_index)is designed to locate the corresponding closing parenthesis for a given open parenthesis in the SMILES string. This is crucial for identifying the boundaries of branched substructures. Similarly,find_opening_parenthesis(s, close_index)identifies the opening parenthesis corresponding to a closing parenthesis, enabling proper identification of substructures. These functions ensure that the branching parts of the molecules are accurately interpreted, which is essential for correctly assigning functional groups. -

The function

find_cycle_number(s)is developed to parse through the SMILES string and identify the largest numeric index used for ring closure. This index represents the total number of rings in the compound. For example, if a compound contains three rings, its SMILES notation will include ring closure indicators numbered 1, 2, and 3. Each ring is assigned a specific index sequentially as it is encountered while writing the SMILES. Therefore, the largest numeric index in the SMILES indicates the total number of rings present in the structure.

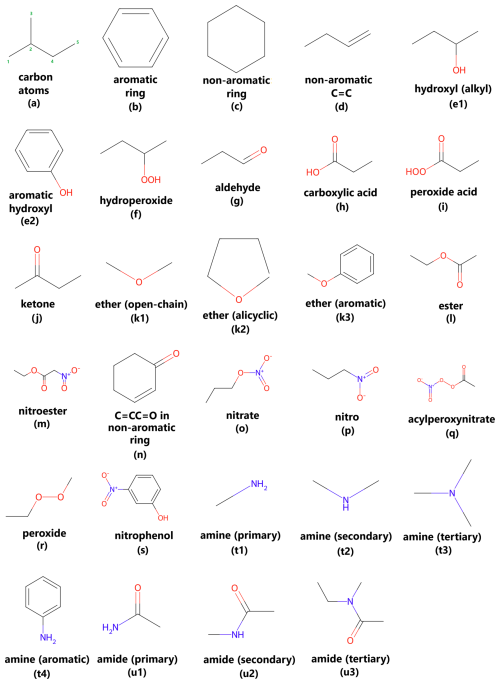

To illustrate the importance of correctly matching parentheses in the algorithm, consider the following example. The pattern O=C1C(=C...1...)... at the beginning of a SMILES notation may suggest the presence of a C=C−C=O group within a non-aromatic ring (such as in cyclohex-2-enone, see example (n) in Fig. 1). The parentheses must correspond to each other in the above-mentioned pattern, enclosing the second occurrence of '1'. For instance, in the SMILES string O=C1C(=CC)CC(CC1)C, although it initially appears to match the pattern, the second '1' does not reside between the matching parentheses. As depicted in Fig. 2a, this structure places the C=C bond outside the ring, diverging from the characteristics of the intended functional group. By contrast, in the strings O=C1C(=CCCC1)C and O=C1C(=C(C(C)C(C)C)CCC1)C, the second '1' is properly enclosed within the matching parentheses (highlighted in bold), adhering to the pattern and satisfying the criteria for detecting the C=C–C=O group within a non-aromatic ring. Notably, the latter example contains more carbon atoms, making it easier to count and visually distinguish the structure's complexity. This highlights the versatility of the algorithm in handling SMILES strings of varying complexity, even when the carbon atom count increases.

Figure 2Structural representations of SMILES strings demonstrating the importance of correct parenthesis matching for the identification of C=C−C=O groups in non-aromatic rings. Structure (a) (O=C1C(=CC)CC(CC1)C) incorrectly places the C=C bond outside the ring, while structures (b) and (c) (O=C1C(=CCCC1)C and O=C1C(=C(C(C)C(C)C)CCC1)C) adhere to the correct pattern.

2.1.3 Aromatic and non-aromatic rings

Organic molecules often contain cyclic structures, which can either be aromatic (such as benzene rings) or non-aromatic (such as cyclohexane). The model uses two specific functions, aromatic_ring(s) and non_aromatic_ring(s), to identify and quantify these rings based on the SMILES notation. The function aromatic_ring(s) utilizes the previously described find_cycle_number(s) function to identify the largest ring number within the SMILES string. This number represents the highest numeric indicator for cyclic structures (e.g., c1ccccc1 in SMILES denotes a benzene ring with the digit '1' marking the ring). The function then constructs a list of potential aromatic ring representations, such as 'c1', 'c2', …, 'cn', where 'n' is the index of the last detected ring showing how many rings are in the structure. It then iterates over the SMILES string, counting the occurrences of these aromatic rings. To avoid double-counting, the final count is halved, since each ring closure is represented by two digits (e.g., c1...c1). The function returns the total number of aromatic rings present in the molecule.

Similarly, the non_aromatic_ring(s) function detects non-aromatic cyclic structures. Like the aromatic ring detection, the function constructs list of possible ring representations, including combinations such as 'C1', 'N1', 'O1' and so on, based on the largest ring index. The function returns the total number of non-aromatic rings detected in the molecule.

2.1.4 Non-aromatic double-bonded carbon atoms

In addition to identifying cyclic structures, the model also detects non-aromatic double bonds between two carbon atoms, a common feature in organic molecules that strongly influences their chemical and physical properties. The function double_bound_nonaromatic_carbons(s) is designed to identify occurrences of double-bonded carbon atoms in non-aromatic structures. This function operates by scanning the SMILES string for occurrences of =C, which indicates a double bond involving a carbon atom. The following steps are used to ensure accurate detection of non-aromatic double bonds:

-

Ring number detection: as with previous functions,

find__number(s)is employed to identify the largest numeric ring closure indicator, which is used to distinguish between ring-bound and non-ring-bound carbons. -

Pattern matching: the function scans the SMILES string for = C, which denotes a double bond with a carbon atom. Upon finding such occurrences, additional checks are performed to ensure the carbon atoms involved in the double bond are not part of an aromatic system:

- i.

Straight chains: if the string preceding the double bond (

=C) contains another capitalC, it is counted as a non-aromatic double bond (e.g.,C=CinCC=CCCC). - ii.

Ring systems: if the string preceding the double bond contains a numeric ring closure indicator (e.g.,

C1=CinC1=CCCC1), it is also recognized as part of a non-aromatic ring structure. - iii.

Parentheses handling: the function is equipped to handle more complex structures, such as those involving nested parentheses (e.g.,

C(...(...(...)...)...)=CinCC(C(C(CC)C)C)=CC). In SMILES, nested parentheses represent branching in a molecule occurring when an atom in the main chain of the molecule is connected to one or more side chains. The parentheses indicate the start and end of each branch, and nesting occurs when a branch contains another branch. It uses thefind_opening_parenthesisfunction to locate the corresponding opening parenthesis and verify that the bond belongs to a non-aromatic system.

- i.

This approach ensures that double bonds within non-aromatic systems are accurately counted, even in cases where the SMILES notation involves branching or ring structures.

2.1.5 Alkyl hydroxyl and hydroperoxide groups

The function hydroxyl_group(s) is designed to identify hydroxyl groups (−OH) present in the SMILES representation of a compound. To ensure accurate detection, the function incorporates specific conditions to avoid miscounting hydroxyl groups that are in specific arrangements that do not denote targeted simple hydroxyl groups. For example, it ensures that carboxylic acids with hydroxyl groups connected to carbonyls (C=O) are not mistakenly counted as plain hydroxyls. One important condition is that the C(O) pattern (a hydroxyl group in SMILES) must not be followed by =O or (=O), which would indicate a carboxylic acid rather than a hydroxyl group. The following steps outline how this function operates to ensure accurate detection of hydroxyl groups:

-

Ring number detection: the

find_cycle_number(s)is utilized to determine the presence of cyclic structures to establish whether the hydroxyl group is part of a ring or a straight-chain structure. -

Pattern matching: the function examines the SMILES string for various patterns that denote hydroxyl groups, primarily focusing on terminal hydroxyls, where the function checks if the hydroxyl group appears at the end of the SMILES string, represented as “O” or “C–O” configurations (e.g.,

CCCCO) or branching with parenthesis (e.g.,CCC(C)O). It evaluates whether the hydroxyl group appears within a branching structure or a cyclic component, recognizing patterns such asC(...)OorC1(...)O. Moreover, the function is equipped to deal with complex SMILES representations involving nested parentheses, ensuring that all possible hydroxyl configurations are evaluated (e.g.,(O)inCC(O)CCandCC(C)(O)CC). -

Conditions for counting: specific conditions are implemented to avoid miscounting hydroxyl groups that are either in specific arrangements that do not denote targeted hydroxyl group or are redundant in cyclic structures. In this regard, the function ensures that carboxylic acids with hydroxyl groups connected to carbonyls (C=O) are not mistakenly counted as plain hydroxyls. For example, in the SMILES representation

C(O)=O, the hydroxyl group is not counted because it is directly bonded to a carbonyl group. As an example, one condition to take into consideration is that theC(O)pattern (a hydroxyl group in SMILES) does not proceed with=Oand(=O). Additional criteria influencing this classification are embedded in the code.

It is important to note that the detection of hydroperoxide groups (−OOH) in VaPOrS follows a similar pattern as that used for hydroxyl groups (−OH). The key difference in recognizing hydroperoxide groups is that instead of detecting single oxygen atoms (O), the algorithm would look for two consecutive oxygen atoms (OO). This adjustment is made throughout the function hydroxyl_group(s) and is provided in a new function as hydroperoxide_group(s) to recognize and count hydroperoxide groups in addition to hydroxyl groups.

In cyclic structures, hydroxyl groups are excluded if they are connected directly to aromatic rings (e.g., c1ccc(O)cc1). This is due to them being considered as another essential functional group called aromatic hydroxyl in the SIMPOL method. The sequential subsection explains how this functionality is described and detected by the developed algorithm.

2.1.6 Aromatic hydroxyl group

The function aromatic_hydroxyl_group(s) scans the SMILES string for the presence of hydroxyl groups attached to aromatic systems. The function looks for specific patterns that indicate an aromatic hydroxyl group, focusing on the position of the hydroxyl group in the SMILES string:

- i.

Hydroxyl at the end: the function checks if the SMILES string ends with

O, ensuring that the preceding character(s) form part of an aromatic ring. For the SMILES string such asc1cccc1O, where the hydroxyl group is at the end of the SMILES, it detects the hydroxyl group attached to an aromatic ring(c1). - ii.

Hydroxyl at the start: the function checks if the SMILES starts with the

Oc1pattern, indicating a hydroxyl group attached to the first aromatic ring in the compound.Oc1ccwould be recognized as having an aromatic hydroxyl group at the start. - iii.

Hydroxyl in the middle: the function searches for occurrences of the pattern

c(O)orc(...O)where a hydroxyl group is attached to an aromatic ring somewhere in the middle of the SMILES. For the SMILESc1cc(O)cc1, the hydroxyl group is identified within the ring. In strings such asc1c(c...c1O)C, the hydroxyl group connected to the aromatic ringc1is correctly identified. - iv.

Hydroxyl at the end of a branch: the function checks for cases where a hydroxyl group is part of a branch but still attached to an aromatic ring. For example, in

c1c(c...)O, where the hydroxyl group is at the end of a branch attached to an aromatic ring, it detects the correct structure. - v.

Handling nested parentheses: if multiple parentheses are involved, the function ensures that the correct ring and attachment points are identified. For example, the pattern

...c1...(...c1)...)O)...appearing in SMILES likeCC(c1cc(c(cc1)CC(C=O)C)O)Cidentifies the aromatic hydroxyl correctly. - vi.

Hydroxyl connected to the index of aromatic carbon: the function ensures that hydroxyl groups are also counted if they are directly attached to index of carbon atom in an aromatic ring (represented by

cin SMILES notation). Inc1(O)cccc1, the hydroxyl group attached toc1is correctly counted.

As the final filtration step, after identifying a hydroxyl group in the aromatic ring, the algorithm also checks for the presence of a nitro group within the same aromatic ring. If a nitro group is found in addition to the hydroxyl group, the compound is no longer classified as an aromatic hydroxyl group; instead, it is categorized as a nitrophenol compound. A detailed explanation of this functional group is provided in a subsequent subsection.

2.1.7 Aldehyde group

The function aldehyde_group(s) is tasked with locating aldehyde groups (i.e., terminal carbonyl groups) within a given SMILES string. The following steps illustrate how this function operates:

-

Pattern matching: the function checks the SMILES string for various patterns that indicate the presence of aldehyde groups, focusing on:

- i.

Aldehyde at the beginning: the function checks if the SMILES starts with common aldehyde patterns. For instance, In

O=CC,C(=O)C,O=Cc, andC(=O)cpatterns appearing in the SMILES, the function counts these as aldehydes. - ii.

Aldehyde at the end: the function checks if the SMILES ends with the characteristic

C=Opattern. For example, the last three characters are checked to beC=O. If preceded by aC, such as inCC=O, it counts as an aldehyde. As another example with cyclic structures, forC1C=Oas the last characters of a string where the aldehyde is linked to a cyclic structure, this is also counted. - iii.

Aldehyde in the middle of the SMILES notation (not structure): the function scans for

C=Opatterns within the SMILES string. For the structure such asC(C=O)..., the carbonyl group may appear in the middle of the SMILES string. However, this still corresponds to a terminal carbonyl group in the molecular structure, i.e., an aldehyde and not a ketone. This distinction is important: while the SMILES position may suggest a non-terminal group, the actual bonding context in the molecular structure confirms its identity as an aldehyde. - iv.

Aldehyde at the end of a branch: The function examines occurrences of

C=O)at the end of branches. For example, the appearance ofCC=O)...pattern in the SMILES counts it as an aldehyde.

- i.

-

Conditions for counting: specific conditions are established to ensure accurate counting and avoid misidentification of aldehyde groups:

- i.

Connected to carbon atoms: the function ensures that aldehydes are counted only if they are connected to carbon atoms directly. In

C(C=O)...pattern, for example, the C preceding theC=Oindicates a valid aldehyde. - ii.

Handling cyclic structures: the function accounts for rings, ensuring that aldehydes connected to cyclic structures are counted appropriately. For example, in

C1(...)C=O, the presence ofC1before the aldehyde indicates a connection to a ring, thus counting it as an aldehyde. - iii.

Parentheses handling: the function effectively manages nested structures, checking for relevant connections before counting. As an instance, if

C=Ois branched from a carbon e.g., inC(...)(C=O)...pattern, it counts as an aldehyde.

- i.

2.1.8 Carboxylic and peroxy acid groups

The function carboxylic_acid_group(s) is designed to identify the presence of carboxylic acid groups within a compound. The detection is briefly broken down into the following steps:

-

Carboxylic acid at the beginning: the function begins by checking if the SMILES string starts with the characteristic patterns for a carboxylic acid group. Allowed prefixes are

O=C(O)orOC(=O). For example, in the SMILES stringO=C(O)CC, the carboxyl groupO=C(O)at the beginning of the molecule is detected. -

Carboxylic acid as the last characters: the function checks if the SMILES string ends with patterns such as

C(=O)OandC(O)=O, indicating a carboxylic acid group at the end of the molecule. As an instance, for the compoundCCC(=O)O, the carboxylic acid group at the end is correctly identified asC(=O)O. -

Carboxylic acid in the middle of the SMILES: the function searches for occurrences of the carboxylic acid group in the middle of the SMILES string using the patterns like

C(=O)O)andC(O)=O). Each time one of these patterns is found, the function increases the count of carboxylic acid groups. For instance, in the SMILESCC(C(=O)O)C(C(O)=O)C, the carboxylic acid groupsC(=O)OandC(O)=Oin the middle are detected.

The detection of peroxy acid groups follows a similar pattern to that used for carboxylic acid groups within the model. The key difference in recognizing peroxy acid groups lies in the algorithm's adjustment to look for two consecutive oxygen atoms e.g., C(=O)OO and C(OO)=O instead of single oxygen atoms found in carboxylic acids e.g., C(=O)O and C(O)=O. By implementing this modification throughout the model, peroxy acid functional groups can be counted as well.

2.1.9 Ketone group

The function ketone_group(s) is designed to identify and count the presence of ketone groups in the SMILES string of a compound. These patterns can be located at the start, middle, or end of the SMILES string, as well as within rings. The detection process is divided into several steps:

-

Ketone as the first characters: the function checks if the SMILES string begins with a ketone pattern (e.g.,

O=C(C...)CinO=C(CCC)CorO=C(c...)C...inO=C(c1ccccc1)CCO). These patterns represent the ketone group at the beginning of the SMILES string, followed by either a non-aromatic or aromatic carbon. The function also handles ketones connected to rings, such asO=C1...inO=C1CCCC1indicating a carbonyl group attached to the first position of a ring. Note that although the ketone group appears at the start of the SMILES string, it may not be at the beginning of the molecular structure itself. The pattern is recognized based on bonding context, not string position. -

Ketone as the last characters: the function checks if the SMILES string ends with

=O, indicating a ketone group at the end of the molecule. If the ketone is ring-connected (e.g.,C1CCCC1=O), additional checks ensure the presence of a carbonyl group within the ring. Similarly, the ketone group may appear at the end of the SMILES notation, but in the molecular structure, it could be part of a cyclic or internal configuration. The detection logic is based on chemical connectivity, not linear SMILES order. -

Ketone in the middle of the SMILES: the function searches for ketone groups within the middle of the SMILES string using patterns such as

C(=O), representing a carbonyl group between two carbons. Also, the function carefully checks if the ketone is branched, ensuring accurate identification of the ketone group in the middle. As an example, in the SMILES stringCC(=O)C, the middle ketone groupC(=O)is detected between two carbon atoms. -

Handling parentheses: the function accounts for complex SMILES structures that contain nested parentheses. It ensures that ketone groups within branches (e.g.,

...C(C(C...)=O)...inCC(C(CCC)=O)CC) are properly identified by finding the matching opening and closing parentheses.

2.1.10 Open-chain, alicyclic, and aromatic ether groups

Three functions open_chain_ether(s), alicyclic_ether(s), and aromatic_ether(s) are defined to distinguish between ethers present in the SMILES notation (open-chain, alicyclic, and aromatic ethers). Below is a breakdown of the major components and logical flow within this algorithm.

A key part of the function's operation involves detecting in-ring ethers. The function starts by searching for the sequence "OC" within the SMILES string, which is the primary sequence of the ether functional group. The other carbon atom bonded to the oxygen atom of the "OC" sequence (e.g., COC or C(OC...)) is then searched to identify if the ether function is alicyclic or open-chain. For each occurrence, the algorithm checks if the sequence is part of a non-aromatic ring by comparing its position relative to the numerical ring indicators. This is done by locating the positions of ring closure numbers (e.g., C1...C1) relative to the ether group. If the ether group lies outside the ring closure points (e.g., C1CCCC1COCC), it is classified as an open-chain ether. On the other hand, if the ether group is found within the two identical ring numbers (e.g., C1...COC..C1), the algorithm hesitates if the ether is part of the ring or an open-chain type. Therefore, the function employs a nested structure-parsing approach to clarify this issue. It uses parentheses to detect branching points or nested structures within the molecule. The algorithm carefully traces the boundaries of rings and other nested structures simultaneously. If the ether group is embedded within parentheses and surrounded by ring numbers (e.g., pattern C1...(...COC...)...C1 in SMILES C1CC(COC)CC1), it is open-chain ether, while if it follows patterns, such as ...C1...(...COC...C1...)..., it is alicyclic (e.g., SMILES C1C(COCC1C)CC). On the other hand, the function also checks if the ether is located near the start or end of a ring closure, which would indicate that the ether is alicyclic (e.g., pattern C1...C(...)O1), otherwise, it would be an open-chain ether. In compounds containing multiple rings, the function iterates through each ring. It systematically searches for ether groups within and around each ring, ensuring that all possible locations are checked for ether group presence. If the ether group is attached to a non-aromatic ring, special handling is performed to ensure accurate detection.

On the other hand, for aromatic ethers, the model looks for occurrences of 'Oc' within the SMILES string. The logic checks different cases based on what precedes 'Oc':

-

Simple alkyl group (

'C'before'Oc'): this detects linear aromatic ethers where the oxygen is connected directly to an alkyl group (e.g.,COc1ccccc1). -

Nested structures with parentheses: the model handles cases where the ether group is part of a complex structure. If the ether group is surrounded by parentheses, the model traces the original alkyl chain, ensuring it connects to an aromatic ring (e.g., patterns

C(OcandC(...)Ocin SMILESCC(Oc1cccc1)CCCandCC(C(O)=O)Oc1cccc1). -

In case the ether group is attached to one aromatic and one non-aromatic ring, the model iterates over possible ring numbers to find ether groups (e.g.,

'C1CCCC1Oc1ccccc1'where'C1'is part of a ring and'Oc1'is the ether group). The same logic is applied to nested structures with parentheses, ensuring that the correct connection between alkyl and aromatic groups is maintained. -

The model repeats the search, but this time looking for

'OC', where the aromatic group comes first (e.g.,'c1cccc1OC'where'c1'indicates an aromatic ring and'OC'is the ether). Similar checks are performed for direct aromatic ether group connection ('c1OC'), complex nested structures (e.g.,c1(OC)ccc1andc1cc(OC)cc1), and parentheses-based structures (e.g.,c1cc(ccc1)OC).

2.1.11 Ester and nitroester groups

The developed function, ester_group(s), identifies and quantifies ester groups within a given SMILES string. The ester group is characterized by the bonding of a carbonyl group (C=O) to an alkoxy group (O–R). This pattern is typically (not always) represented in SMILES as C(=O)O, and variations in its placement within the molecule must be accounted for. For instance, when analyzing the ester group, if the alkoxy group (−OR) shows up in the SMILES first and then the carbonyl group (C=O), common patterns, such as ...C(...)(...)OC(=O)C... (e.g., in CC(CO)(C)OC(=O)CC with bolded characters) and ...C(...)(OC(=O)C...)... (e.g., in CC(CO)(OC(=O)CC)C with bolded characters) are identified. Conversely, if the SMILES notation proceeds from the acid-side carbon (i.e., carbon attached directly to the carbonyl group in the ester bond −C(O)OR), ester groups may be represented as ...C(...)(...)C(=O)OC... (e.g., in CC(CO)(C)C(=O)OCC with bolded characters) or ...C(...)(C(=O)OC...)... (e.g., in CC(CO)C(=O)OCC)C with bolded characters). These patterns ensure that ester groups are recognized irrespective of their position within a molecule.

The above-mentioned patterns with several other ones related to ester group may be determined whether at the start, middle, or end of the SMILES string:

-

If the ester group is at the beginning, the function looks for patterns such as

O=C(C...)OC...andO=C(OC...)C(e.g., in SMILESO=C(CCO)OCCCandO=C(OCCC)CCO), where the group starts with the double-bond oxygen atom. -

For esters embedded within the middle of a SMILES string, the function searches for the ester signatures such as

C(=O)OandOC(=O), confirming that the carbonyl group is bonded to the oxygen atom of the alkoxy group and followed by a suitable molecular fragment. For instance, in a SMILES notation likeCCC(=O)OCCandCCOC(=O)CC, the ester group is correctly identified as part of the main chain. -

If an ester group is located at the end of the SMILES string, the function identifies patterns such as

)=Osequence as an indicator of the terminal carbonyl group, followed by the appropriate bonding structure. This ensures that molecules likeCC(OCC)=Oare correctly parsed with the ester group assigned to the end of the chain. -

In cases of aromatic esters, where alternating single and double bonds are common, the function adapts the detection logic to properly handle aromaticity. For example, it correctly identifies the ester group in a molecule like

O=C(OCCC)c1ccccc1, where the ester is attached to an aromatic benzene ring. -

The algorithm is designed to detect esters even in highly branched molecules. For instance, in a molecule like

CCC(C(=O)OCCC)(C)CC, the ester group is part of a branching structure, and the function ensures it is accurately parsed by considering the nested arrangement of atoms.

On the other hand, the model locates the starting and ending positions of the acid-side branch for the ester group and searches for the presence of a nitro group (N(=O)=O) in the branch. If a nitro group is detected, the compound is classified as a nitroester, and the nitroester_number is incremented. In cases where no nitro group is present, the compound is classified as a regular ester, and the ester_number is incremented accordingly.

2.1.12 C=CC=O in non-aromatic rings

The function nonaromatic_CCCO(s) is designed to quantify C=C–C=O substructures in a molecular SMILES notation. This section explains how the function works.

Since the substructure of interest occurs within rings, the function first checks whether the molecule contains any cyclic structures. The function uses find_cycle_number(s) to determine if any rings exist in the molecular structure. If no rings are found, the function terminates early. When rings are detected, the function proceeds to locate their positions within the SMILES string.

The next step is to detect the C=C–C=O group within the identified rings. This involves scanning the part of the SMILES string that represents each ring and checking for the specific pattern of atoms and bonds. Several important aspects are considered during this analysis:

-

Pattern search: within the extracted portion, the function looks for patterns that match the C=C−C=O group. For example, the presence of

C=Oat the start of a ring followed by a conjugated double bond (C=C) within the ring (e.g., patternO=C1...C(...)=C1bolded in SMILESO=C1CCC(OC)=C1C), or variations where the C=C and C=O groups may be spaced by additional atoms, or where they may appear in different locations within the ring (e.g., pattern...1...C(=O)C(...)=C...1...bolded in SMILESO=C1CC(=O)C(CC)=CC1C). -

Handling complex ring structures and nested rings: the function accounts for these complexities by carefully navigating through the parentheses and ensuring that the entire cyclic structure is examined for the C=C−C=O group (e.g., pattern

...C(=C(C(...1...)=O)...)...bolded in SMILESCC1C(=C(C(CC1C)=O)C)CC).

2.1.13 Nitrate group

The nitrate_number(s) function identifies and quantifies nitrate functional groups within the provided SMILES notation. This function examines specific configurations characteristic of nitrate, including the standard nitrate structure ON(=O)=O, the quaternary form O[N+](=O)[O-], the N-nitro structure O=N(=O)O, and variations like O=[N+]([O-])O and [O-][N+](=O)O, which collectively reflect diverse bonding scenarios in nitrate chemistry. The function calculates the count of each of these configurations and aggregates them to derive the total number of nitrate groups present.

2.1.14 Nitro group

The identification of nitro groups is executed through the nitro_group(s) function, which analyzes the SMILES notation to quantify nitro functional groups. This function employs a series of search operations to locate specific nitro structures, notably N(=O)=O, O=N(=O), and various ionic forms such as [N+](=O)[O-], O=[N+][O-], and [O-][N+](=O). Each search utilizes a loop that not only finds occurrences of these structures but also ensures that adjacent atoms do not disrupt the nitro configuration. Specifically, it checks that there is no oxygen atom directly connected to the nitro group, which would suggest an alternative bonding scenario (i.e., nitrate group). As the final filtration step, the algorithm verifies whether the identified nitro group is not part of an aromatic ring (i.e., benzene). If this condition is met, it then checks for the presence of a hydroxyl group in the ring according to Sect. 2.6. If no hydroxyl group is found, the nitro group is counted independently. However, if a hydroxyl group is present, the compound is categorized as a nitrophenol group. A detailed explanation of this functional group is provided in a subsequent subsection.

2.1.15 Nitrophenol

The function nitrophenol_group(s) is designed to identify and count the number of nitrophenol groups. After identifying aromatic hydroxyl group, the function then checks for the presence of a nitro group in the same aromatic ring within the SMILES string:

-

As the last character sequence: it inspects whether the string ends with the motif

N(=O)=O, which signifies a nitrophenol. The function checks if it is connected to the aromatic cyclic structure by examining the characters before it. For example, if the character is an aromatic ring identifier, the counter is incremented accordingly (e.g.,c1cc(O)ccc1N(=O)=O). -

As the first character sequence: the function checks if the string starts with the pattern

O=N(=O)c1, indicating a nitrophenol positioned within the SMILES string (e.g.,O=N(=O)c1cc(O)ccc1). If this pattern is detected, the counter is incremented. -

As middle character sequences: a loop is employed to search for occurrences of patterns such as

c(N(=O)=O), which indicates that nitrophenol is positioned within the structure (e.g.,c1cc(N(=O)=O)cOcc1O). Each time this pattern is found, the counter is increased. The function also iterates through the previously established list of rings to search for patterns of the formj(N(=O)=O)(wherejis an aromatic carbon identifier). Whenever a match is found, the counter is incremented (e.g.,c1(N(=O)=O)cc(O)ccc1).

2.1.16 Acylperoxynitrate group

The function carbonylperoxynitrate_group(s) is designed to detect the presence of acylperoxynitrate groups within a given SMILES string s. This function systematically counts occurrences of several distinct structural motifs characteristic of acylperoxynitrates, including OON(=O)=O, OO[N+](=O)[O-], O=N(=O)OO, O=[N+]([O-])OO, and [O-][N+](=O)OO. The function aggregates the counts of these motifs into a single variable, carbonylperoxynitrate, which represents the total number of acylperoxynitrate groups identified.

2.1.17 Peroxide group

The function peroxide_group(s) is engineered to identify and quantify peroxide groups. The function first determines the number of cyclic structures within the SMILES string by calling the find_cycle_number(s) function. If cyclic structures are found, a list of ring identifiers, comprising both carbon (C) and aromatic (c) rings, is generated to facilitate later checks. Subsequently, the function employs a loop to search for occurrences of the OOC motif, which signifies the presence of peroxy groups. Each iteration of the loop calls s.find('OOC',...) to locate the next occurrence of the motif. Multiple conditions are assessed to ensure that the identified OOC is correctly positioned relative to other atoms or rings:

-

Adjacent carbon or aromatic carbon atoms: if the character preceding

OOCisC,CxorcX(x=1,2,...is cyclic index), indicating that OOC is bonded to a carbon atom, theperoxide_numberis incremented (e.g.,CCCOOCC,C1CCCC1OOCCandCc1cccc1OOC). -

Branching structures: if the character before

OOCis a parenthesis, the function retrieves the index of the last corresponding parenthesis beforeOOCand verifies that the atom preceding this parenthesis is a carbon atom or an aromatic ring. If so, the counter is increased. For example, when the character beforeOOCis a closing parenthesis, the function checks whether theOOCis connected to a carbon atom in a similar manner as described previously. This involves searching back to the last opening parenthesis and ensuring the atom connected to that parenthesis is a carbon atom or part of a cyclic structure (e.g., pattern...C(...)OOC...bolded in SMILESCCC(CO)OOCCC).

These checks comprehensively ensure that only valid peroxide groups are counted, accounting for the complex connectivity possible within SMILES representations. The function ultimately returns the peroxy_number, providing a quantitative measure of peroxide groups within the molecular structure.

2.1.18 Aromatic amine group

Following the identification of aromatic rings, the function aromatic_amine_group(s) locates nitrogen atoms (N) within the SMILES string and determines their bonding to aromatic carbons.

-

Direct bond to aromatic carbon (

cN): if nitrogen (N) is found immediately following an aromatic carbon(c), it is counted as part of an aromatic amine group. To ensure the nitrogen atom belongs to an aromatic amine and not a nitro group (−NO2), the model incorporates an additional condition. -

Nitrogen in numbered rings (

c1N,c2N, etc.): if nitrogen is attached to a carbon in a numbered ring, such asc1N, the nitrogen is identified as part of an aromatic amine group. -

Parenthetical structures

(c(...)N): in cases where nitrogen is attached within parentheses following a cyclic group, the function checks if the nitrogen is part of an aromatic ring by verifying the bonding pattern of the cyclic carbon to the nitrogen. Parentheses in SMILES represent branching, and this function ensures that any branching nitrogen groups attached to aromatic carbons are also detected.

The function iterates through the SMILES string to ensure that all occurrences of nitrogen atoms are evaluated. The bonding pattern of each nitrogen atom is assessed against the aromatic rings identified in the first step. If the nitrogen atom is confirmed to be attached to an aromatic ring and not part of a nitro group, it is counted as part of an aromatic amine group. The total count of such groups is stored in the variable aromatic_amine_number and returned as the output of the function.

2.1.19 Primary, secondary, and tertiary amide and amine groups

The model is designed to detect and count primary, secondary, and tertiary amide and amine groups in a molecule represented by a SMILES string. A primary amide has the functional group structure −C(=O)NH2, and the model identifies both simple and branched forms of this group. To differentiate between primary amides and primary amines, the model specifically excludes patterns without a double-bonded oxygen, i.e., −C(…)NH2 where “…” is not =O, thereby ensuring correct identification of amide groups versus amine counterparts.

-

The function first identifies primary amide groups located at the beginning of the SMILES string by searching for patterns such as

O=C(N)orNC(=O), as seen in SMILESO=C(N)CCCOandNC(=O)CCCO). It also detects primary amides at the end of the SMILES string by tracing patterns likeC(=O)NandC(N)=O, as inCCOCC(=O)NandCCOCC(N)=O. To identify primary amine groups at the beginning or end of the strings, the function checks for similar patterns but without a carbonyl group (=O). In other words, if a nitrogen is bonded to a carbon that does not carry a =O, it is interpreted as an amine rather than an amide. For example,C(N)CCCO,NCCCCO,CCOCCN, andCCOCCNare recognized as containing primary amine groups. -

The model also identifies primary amides within branches or internal positions in the molecule by searching for specific patterns, such as

C(=O)N)andC(N)=O, as seen in the SMILES stringsCC(C(=O)N)CCandCC(C(N)=O)CC. To identify primary amine groups in similar positions, the model checks for the absence of the double-bonded oxygen (=O) on the carbon adjacent to the nitrogen. This results in patterns likeCN)inCC(CN)CCandCC(CN)CC.

For secondary and tertiary amides, the model similarly searches for patterns where the nitrogen atom is bonded to two or three carbon atoms, respectively. Secondary amides have the structure −C(=O)NR, where R represents an alkyl group starting with a carbon atom attached to the nitrogen atom, and tertiary amides have the structure −C(=O)N(R)R′, where both R and R′ are alkyl groups starting with carbon atoms attached to the nitrogen atom. The model identifies these structures by recognizing the presence of additional carbon attachments to the nitrogen atom. For secondary amides, the function searches for patterns that indicate the nitrogen is bonded to one additional carbon group, distinguishing them from primary amides by checking for two single bonds to nitrogen, along with the carbonyl group. Similarly, for tertiary amides, the function detects two alkyl groups attached to the nitrogen atom in addition to the carbonyl group. Once these amide patterns are identified, the model applies the same exclusion method for the double-bonded oxygen, converting these amides into their corresponding secondary and tertiary amines. For secondary amines, the nitrogen is attached to two carbon atoms, and for tertiary amines, the nitrogen is bonded to three carbon atoms. This method ensures that the correct amide or amine group is identified and classified, whether it is primary, secondary, or tertiary, based on the number of carbon attachments to the nitrogen atom.

Finally, the model counts the number of carbon atoms in the secondary and tertiary amides that are not part of the R and R′ groups in the structure. This count is considered as the number of carbons on the acid side of the amides. For primary amides, since there are no additional alkyl groups attached to the nitrogen atom, all carbon atoms in the structure are considered to be on the acid side of the amide. This ensures accurate categorization and counting of carbon atoms associated with the amide's acid side, contributing to the overall structural analysis of the molecule.

2.2 Saturation vapor pressure calculation

Once functional groups are identified, VaPOrS converts the detection results into integer values representing the frequency of each group in a given compound. These values are stored in an array and serve as the critical input for property prediction. In the present implementation, the pure-component liquid saturation vapor pressures, excluding the Raoult effect, is calculated using the SIMPOL group-contribution method, in which the total logarithmic vapor pressure is expressed as the sum of contributions from all relevant functional groups as a function of temperature. In the model:

- i.

Matrix B is read from a pre-defined text file containing coefficients of Bk,1, Bk,2, Bk,3, and Bk,4 for each functional group k, according to Table 5 of Pankow and Asher (2008). A select functional group is assigned a value for contribution to saturation vapor pressure in the ith SMILES string (such as hydroxyl, aldehyde, and ketone groups, etc.).

- ii.

Then, bk(T) and are calculated for any given temperature according to Eqs. (1) and (2). The total liquid (saturation) vapor pressure, (atm), is calculated as the sum of all functional group contributions.

where νk,i is the number of groups of type k, bk(T) is the contribution to by each group of type k, and T is the temperature. Also, 0 and L show the reference and Liquid.

- iii.

To fit the saturation vapor pressure data to the Antoine equation (Eq. 3) to enable further use of the saturation vapor pressure values in different applications, the saturation vapor pressure is calculated at 1000 temperature points across a wide range of temperatures from 220 to 450 K according to Eq. (2). The obtained data are then used in a non-linear least squares fitting procedure, which minimizes the difference between the data and the saturation vapor pressure values predicted by the Antoine equation. The Antoine equation parameters (i.e., A, B, and C) are then obtained for each compound.

- iv.

After obtaining the Antoine equation parameters, the vaporization enthalpy relationship can be derived using the Clausius–Clapeyron equation:

Here, ΔHvap(T) is the temperature-dependent enthalpy of vaporization, and R is the universal gas constant. This expression relates the slope of the logarithm of the saturation pressure with respect to the inverse of temperature to the enthalpy of vaporization. The Antoine equation provides a framework to calculate saturation vapor pressure at any given temperature, and this relationship extends the utility of the model by allowing the determination of thermodynamic quantities such as vaporization enthalpy.

- v.

The output is written to a CSV file named by the user (e.g., output.csv), where each line corresponds to the ith compound and its associated data, including its SMILES string, the count of each functional group in its structure, its saturation vapor pressure at 300 K, and its fitted Antoine equation parameters. Figure 3 illustrates a flowchart of the VaPOrS from input to output.

3.1 Saturation vapor pressure

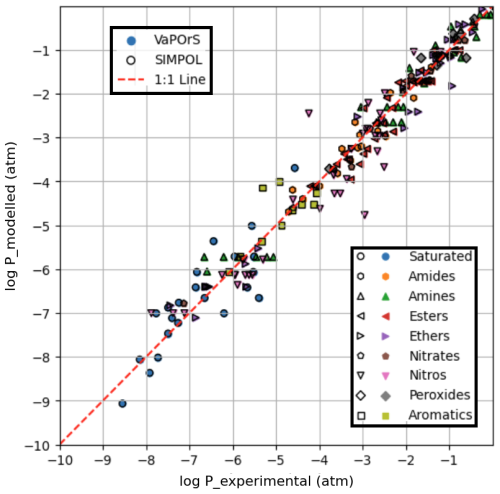

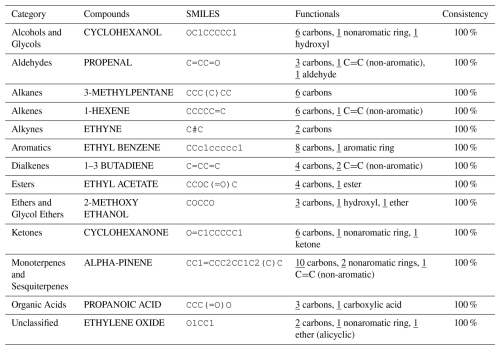

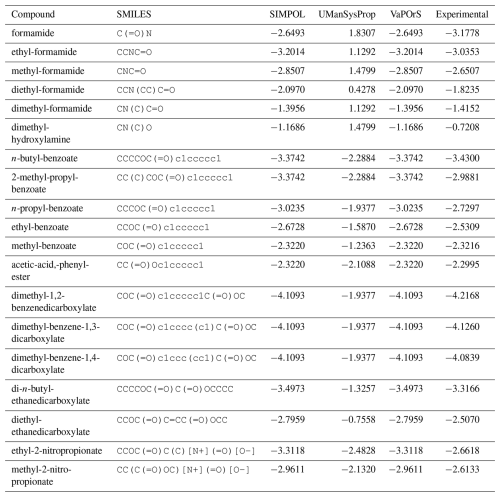

To evaluate the accuracy of the developed automated VaPOrS in predicting the saturation vapor pressures of organic compounds, the model was applied to a subset of the original dataset used to develop the SIMPOL parameterization. Saturation vapor pressures for 224 organic compounds were calculated using VaPOrS and compared against experimental data to assess the accuracy of the implementation and ensure consistency with established results.

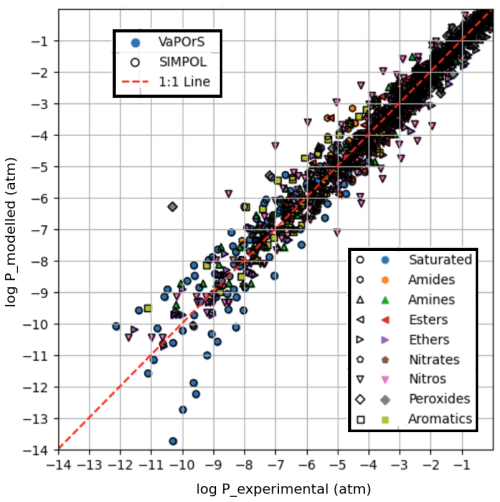

Figure 4 presents a comparative analysis between the saturation vapor pressures computed by the VaPOrS, those manually calculated using the SIMPOL method, and those derived from experimental data reported by Pankow and Asher (2008) using the Antoine coefficients provided in their Supplement, all evaluated at 333.15 K. The x axis represents the experimental saturation vapor pressures, while the y axis represents the numerical values calculated by the VaPOrS (filled symbols with no edge color) and the manually implemented SIMPOL method (black-edged hollow symbols). Due to a complete overlap in the data points, the black-edged symbols from the manual SIMPOL method can be seen over the filled symbols from VaPOrS. A diagonal line is shown in the figure, indicating the ideal correlation where the computed values would perfectly match the measured saturation vapor pressures. Data points positioned close to this diagonal demonstrate a high level of agreement between the two approaches. Quantitatively, the comparison yields an RMSE of 0.4232 and an R2 of 0.9648 for log P, confirming the excellent predictive performance of VaPOrS in reproducing experimental vapor pressures at this temperature.

Figure 4Comparison of saturation vapor pressure values calculated by the VaPOrS (filled symbols with no edge color) and manual SIMPOL method (symbols with no face color and black edges) against measured saturation vapor pressures at 333.15 K. The diagonal line represents the ideal 1:1 correlation, and the proximity of data points to this line indicates the accuracy of both methods in predicting saturation vapor pressures. The overlap in symbols is visible due to the black-edged SIMPOL markers covering the filled VaPOrS symbols.

Figure 5 illustrates the saturation vapor pressure results obtained through the VaPOrS, those manually calculated using the SIMPOL method, and those derived from experimental data reported by Pankow and Asher (2008) using the Antoine coefficients provided in their Supplement, all at seven different temperatures: 273.15, 293.15, 313.15, 333.15, 353.15, 373.15 and 393.15 K. Similar to Fig. 4, the x axis represents the measured saturation vapor pressures, while the y axis displays the values calculated by VaPOrS (filled symbols with no edge color) and manual SIMPOL method (black-edged hollow symbols). This figure includes a larger dataset, allowing for a more comprehensive assessment of model performance across a range of temperatures. Many data points are clustered close to the 1:1 line, yielding an RMSE of 0.5556 and an R2 of 0.9570 for log P, further confirming the effectiveness of the VaPOrS model in predicting saturation vapor pressures for various compounds across different temperatures as well. Some deviations from the line are observed e.g., the experimental values for the nitro and saturated compound saturation vapor pressures and T-dependencies have large uncertainties as seen in Figs. 4 and 5. These discrepancies, which were present in the original dataset, do not undermine the overall trend, which demonstrates strong agreement among the three methods and suggests that the VaPOrS code is reliable and robust across a wider temperature range. Most importantly, we see complete agreement in the output of VaPOrS and SIMPOL.

Figure 5Comparison of saturation vapor pressures obtained from the VaPOrS model, the manual SIMPOL method, and experimental measurements at seven different temperatures (273.15, 293.15, 313.15, 333.15, 353.15, 373.15, and 393.15 K). The x axis represents the measured saturation vapor pressures, while the y axis shows the values calculated by VaPOrS (filled symbols) and the SIMPOL method (hollow symbols with black edges). The diagonal line indicates the ideal correlation, with points near the line demonstrating good agreement between the methods.

3.2 Enthalpy of vaporization

Figure 6 compares the experimental and numerical vaporization enthalpy values reported by the SIMPOL paper with those calculated by the VaPOrS at 333.15 K. The x axis represents experimentally measured values, while the y axis displays the calculated values. The results from the VaPOrS are represented by filled symbols without edge color, indicating a direct prediction from the present model. In contrast, the SIMPOL method results are depicted as symbols with no face color and distinct black edges. The presence of overlapping symbols highlights instances where the calculated values from SIMPOL cover those from VaPOrS. Many points cluster close to the 1:1 line, but deviations are also observed. Quantitatively, the comparison yields an RMSE of 14.4740 and an R2 of 0.6146 for ΔH. These results indicate that while VaPOrS captures the general trend of enthalpy data, the agreement is weaker than for vapor pressures. These discrepancies could be attributed to the structural complexity of certain compounds making intramolecular interactions important and not amenable to simple group additivity predictions, which is also a known limitation in the SIMPOL method itself, or potentially, they could point out issues in the original experimental measurements.

Figure 6Comparison of enthalpy of vaporization values calculated by the VaPOrS (filled symbols without edge color) and manually by SIMPOL method (symbols with no face color and black edges) against experimental measurements at 333.15 K. The diagonal line indicates the ideal 1:1 correlation, showcasing the accuracy of the models. Overlapping symbols are observed, with black-edged SIMPOL markers obscuring the filled VaPOrS symbols.

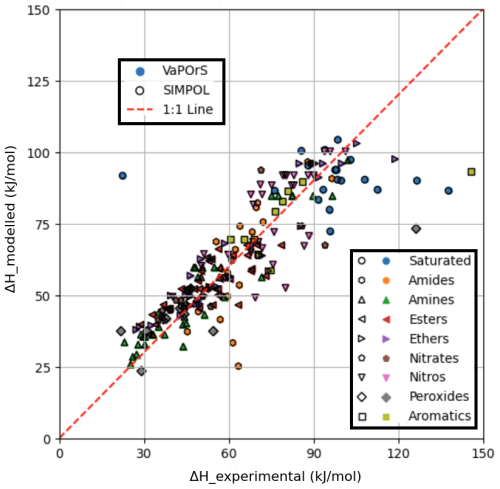

Although the SIMPOL model does not explicitly define an applicability domain, the structure-based framework of VaPOrS offers an opportunity to explore this aspect. Since the code identifies and counts functional groups for each molecule, it can be used to highlight cases where predictions may be less reliable. For instance, compounds such as Decanedioic acid, which contains two carboxyl groups, or Hexanamide, where strong hydrogen-bonding interactions may play a role, or Diethyl-peroxide, which contains a relatively uncommon peroxide group show noticeable deviations from experimental values (see Fig. 7). These examples suggest that compounds with an unusually high number of hydroxyl or carboxyl groups, or those containing less common fragments such as peroxides, often exhibit larger deviations from experimental vapor pressures. Likewise, the co-occurrence of multiple reactive groups within the same molecule (e.g., carbonyl–peroxide combinations) may introduce additional uncertainties. While a systematic applicability domain analysis is beyond the scope of this study, we note that VaPOrS could be extended to provide such functionality, thereby guiding users in assessing the reliability of SIMPOL predictions for structurally complex molecules.

Figure 7Temperature dependence of saturation vapor pressure and enthalpy of vaporization for nine representative organic compounds with nine distinct functional groups predicted by VaPOrS using the Antoine and SIMPOL equations. The left y axis shows the logarithmic saturation vapor pressure (in atm), and the right y axis displays the enthalpy of vaporization (in kJ mol−1). The results demonstrate the data generated by Antoine and SIMPOL methods across the temperature range, with experimental data (Pankow and Asher, 2008) closely matching the theoretical predictions.

3.3 Antoine equation

The results of the fitting process for nine compounds, i.e., 2-methoxy-tetrahydro-pyran, decanedioic acid, methyl-benzoate, phenylamine, hexanamide, phenylmethyl-nitrate, 2-methyl-6-nitrobenzoic acid, diethyl-peroxide, and 2-napthol as representatives of ethers, saturated, esters, amines, amides, nitrates, nitro-compounds, peroxides, and aromatics, respectively, are visualized in Fig. 7. The figure illustrates the temperature-dependent behavior of the vapor pressure and enthalpy of vaporization derived from the Antoine and SIMPOL relationships generated by VaPOrS and compares them with those derived from experimental data reported by Pankow and Asher (2008) using the Antoine coefficients provided in their supplementary material across varying temperatures. The left y axis represents the logarithmic saturation vapor pressure in atmospheres, while the right y axis shows the enthalpy of vaporization in kJ mol−1. This dual-axis representation enables a direct visual comparison between pressure and enthalpy trends as the temperature increases. The fitting results demonstrate a high degree of agreement between the Antoine and SIMPOL curves for all compound classes, implying that the Antoine equation given by VaPOrS can be applied effectively to estimate saturation vapor pressures with good accuracy across a broad range of temperatures, enhancing the utility of the saturation vapor pressure data for various applications.

Using VaPOrS, a detailed comparison was performed between the manual counting and calculation of functional groups and saturation vapor pressures and the automated results generated from the compounds' SMILES notations. The manual counting involved a systematic review of each compound's molecular structure, visually identifying and recording the functional groups, followed by calculating its saturation vapor pressure according to SIMPOL group contributions. This was then cross-referenced with the automated results generated by VaPOrS to ensure consistency. The procedure was performed in three steps described next.

4.1 MCM data

In the first step, a dataset of 126 primary VOCs sourced from the Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM) database are evaluated. While the MCM database provides detailed chemical mechanisms for atmospheric chemistry, its coverage of primary organic compounds is relatively limited compared to the vast diversity of VOCs present in the atmosphere. Nonetheless, it serves as a valuable resource for validation, given its detailed representation of key compounds. Notably, the MCM database not only provides the structures of these compounds but also includes their corresponding SMILES notation, facilitating an accurate assessment of functional group presence through the VaPOrS method. The current version of the MCM (v3.3.1) can be obtained as the file mcm_3-3-1_species_complete.tsv from the MCM archive page (https://www.mcm.york.ac.uk/MCM/about/archive, last access: 20 November 2025).

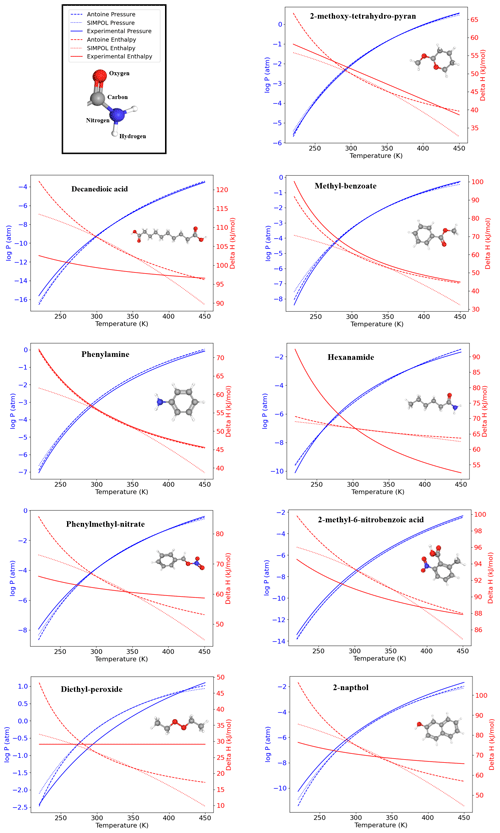

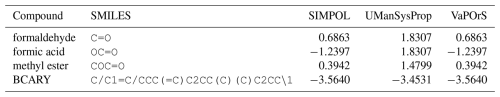

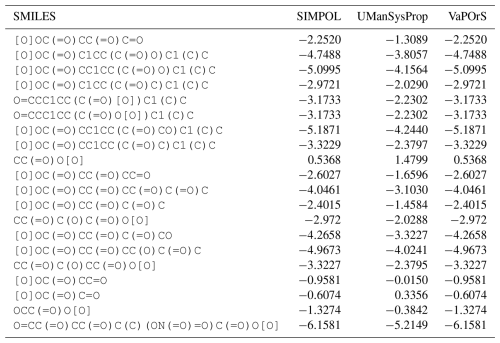

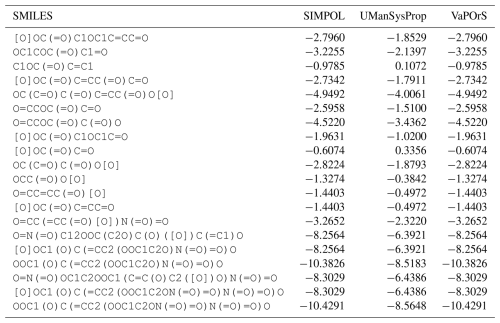

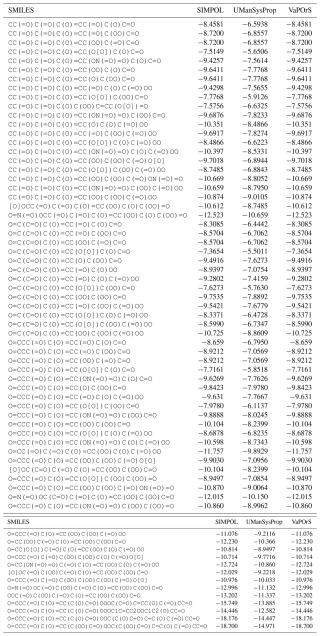

Table 1 presents a sample comparison between the manual and automated counts of the functional groups for representative compounds from several categories in the MCM, including Alcohols and Glycols, Aldehydes, Alkanes, Alkenes, Alkynes, Aromatics, Dialkenes, Esters, Ethers and Glycol Ethers, Ketones, Monoterpenes and Sesquiterpenes, Organic Acids, and Unclassified compounds. As shown, the results from both methods are in complete agreement, with 0 % discrepancy across all cases.

Table 1Comparison of Manual and Automated Counts of Functional Groups for Representative Compounds across Various Categories in the MCM Database.

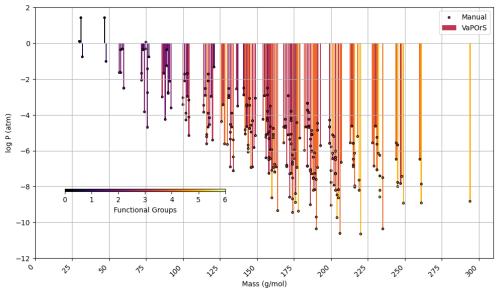

In the second phase, α-pinene and benzene were selected as case studies to evaluate the species formed during their tropospheric degradation via gas-phase chemical processes, focusing on functional group occurrence and saturation vapor pressure. This analysis leveraged the detailed mechanism in the MCM to further validate the automated functional group detection system's accuracy in modeling atmospheric chemistry. For each species, the occurrences of functional groups were manually counted, and saturation vapor pressure was calculated using the SIMPOL method. Their SMILES notation was then input into the VaPOrS to automatically obtain functional group counts and saturation vapor pressures. The saturation vapor pressures obtained through both methods are compared at 298.15 K in Figs. 8 and 9 for α-pinene and benzene, respectively, where the y axis represents the logarithmic saturation vapor pressure and the x axis the molar mass of each species. Automated results are shown as color bars based on the number of detected functional groups, and their manual counterparts are displayed as points. The perfect alignment of points atop bars for each species indicates excellent agreement between both approaches. It is worth mentioning that C6H6N2O11 and CH2O (i.e., NNCATECOOH and HCHO in the MCM) were recognized as the least and most volatile species in the benzene oxidation process. On the other hand, C9H16O6 and CH3O (i.e., C922OOH and CH3O in the MCM) were the least and most volatile species in the α-pinene oxidation process.

Figure 8Comparison of saturation vapor pressure results for tropospheric degradation species of α-pinene. The figure presents the log saturation vapor pressure versus molar mass at 298.15 K for species formed from the tropospheric oxidation of α-pinene according to MCM. Bars show results from the automated VaPOrS code, with colors based on detected functional group number involved in the chemical structure of species, and points reflect manually calculated values. The alignment of points atop bars demonstrates the perfect consistency between automated and manual calculations.

Figure 9Comparison of saturation vapor pressure results for tropospheric degradation species of benzene. The figure illustrates the log saturation vapor pressure versus molar mass at 298.15 K for species derived from benzene degradation according to MCM. The bars represent saturation vapor pressures calculated by the automated VaPOrS code, with colors based on detected functional group number involved in the chemical structure of species, while points indicate manually obtained values. The close alignment of points with bars highlights the accuracy of the automated method relative to manual calculations.

4.2 autoAPRAM-fw data

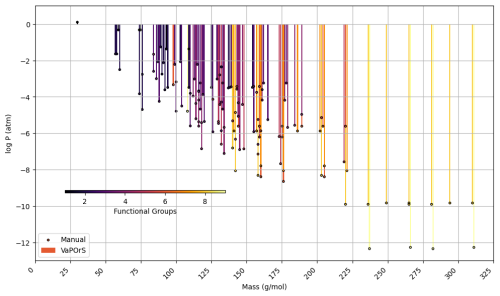

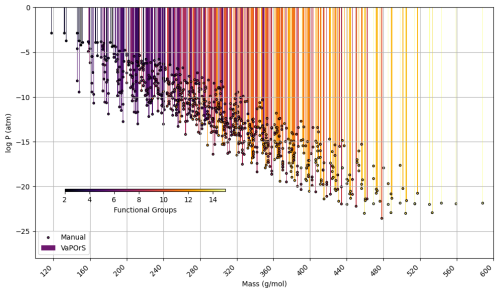

In the third stage of this analysis, the VaPOrS model was utilized to determine the saturation pressures of over 850 potential chemical species produced through the autoxidation of alkoxy and peroxy radicals, which emerge during benzene degradation. The initial radicals were defined by the MCM, with their respective saturation vapor pressures detailed in Fig. 9. Conversely, the products of autoxidation were generated using the autoAPPRAM-fw tool (Pichelstorfer et al., 2024), with their potential structures represented by SMILES notation. Demonstrating its efficiency, VaPOrS analyzed all SMILES entries within a single second, accurately counting the required functional groups and calculating corresponding saturation vapor pressures. The results of these predictions are illustrated in Fig. 10.

Figure 10Comparison of saturation vapor pressure results for autoxidation species of benzene. The figure illustrates the log saturation vapor pressure versus molar mass at 298.15 K for species derived from autoxidation of initial alkoxy and peroxy radicals of benzene degradation. The bars represent saturation vapor pressures calculated by the automated VaPOrS code, with colors based on detected functional group number involved in the chemical structure of species, while points indicate manually obtained values. The close alignment of points with bars highlights the accuracy of the automated method relative to manual calculations.

Figure 10 demonstrates the saturation vapor pressures achieved through the VaPOrS and compares them with their manually calculated counterparts. Automated results are shown as colorful bars based on the number of detected functional groups reaching as high as 15 for some autoAPRAMfw products, and manual results are depicted as points. The compatibility of points atop bars for each species indicates excellent agreement between both approaches.

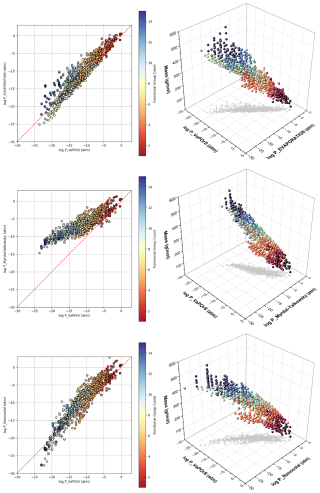

Figure 11 presents 2D and 3D scatter plots comparing the logarithmic saturation vapor pressures obtained at 298.15 K from VaPOrS (log P_VaPOrS) with those predicted by the EVAPORATION (log P_EVAPORATION), Myrdal–Yalkowsky (log P_Myrdal_Yalkowsky), and Nannoolal (log P_Nannoolal) methods for the benzene-derived oxidation and autoxidation products. Each marker represents a compound, with color indicating the number of functional groups in its structure. The red dashed line in the 2D plots signifies the theoretical 1:1 relationship, where the saturation vapor pressures predicted by VaPOrS and the other models would be equivalent. Moreover, the 3D plots include the molar mass of species to give more details of the achieved results.

Figure 11Comparison of logarithmic saturation vapor pressures at 298.15 K predicted by the VaPOrS model (log P_VaPOrS) with those from the EVAPORATION (log P_EVAPORATION), Nannoolal (log P_Nannoolal), and Myrdal–Yalkowsky (log P_Myrdal_Yalkowsky) methods for autoxidation products derived from benzene degradation. Each data point represents a compound, with color indicating the functional group count. The red dashed line in the 2D plots represents the theoretical 1:1 relationship, where predictions from VaPOrS and other methods would be equivalent. The 3D plots include molar mass variation as well to give a comprehensive view of relationships between the parameters.