the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The Eulerian urban dispersion model EPISODE – Part 2: Extensions to the source dispersion and photochemistry for EPISODE–CityChem v1.2 and its application to the city of Hamburg

Sam-Erik Walker

Sverre Solberg

Martin O. P. Ramacher

This paper describes the CityChem extension of the Eulerian urban dispersion model EPISODE. The development of the CityChem extension was driven by the need to apply the model in largely populated urban areas with highly complex pollution sources of particulate matter and various gaseous pollutants. The CityChem extension offers a more advanced treatment of the photochemistry in urban areas and entails specific developments within the sub-grid components for a more accurate representation of dispersion in proximity to urban emission sources. Photochemistry on the Eulerian grid is computed using a numerical chemistry solver. Photochemistry in the sub-grid components is solved with a compact reaction scheme, replacing the photo-stationary-state assumption. The simplified street canyon model (SSCM) is used in the line source sub-grid model to calculate pollutant dispersion in street canyons. The WMPP (WORM Meteorological Pre-Processor) is used in the point source sub-grid model to calculate the wind speed at plume height. The EPISODE–CityChem model integrates the CityChem extension in EPISODE, with the capability of simulating the photochemistry and dispersion of multiple reactive pollutants within urban areas. The main focus of the model is the simulation of the complex atmospheric chemistry involved in the photochemical production of ozone in urban areas. The ability of EPISODE–CityChem to reproduce the temporal variation of major regulated pollutants at air quality monitoring stations in Hamburg, Germany, was compared to that of the standard EPISODE model and the TAPM (The Air Pollution Model) air quality model using identical meteorological fields and emissions. EPISODE–CityChem performs better than EPISODE and TAPM for the prediction of hourly NO2 concentrations at the traffic stations, which is attributable to the street canyon model. Observed levels of annual mean ozone at the five urban background stations in Hamburg are captured by the model within ±15 %. A performance analysis with the FAIRMODE DELTA tool for air quality in Hamburg showed that EPISODE–CityChem fulfils the model performance objectives for NO2 (hourly), O3 (daily max. of the 8 h running mean) and PM10 (daily mean) set forth in the Air Quality Directive, qualifying the model for use in policy applications. Envisaged applications of the EPISODE–CityChem model are urban air quality studies, emission control scenarios in relation to traffic restrictions and the source attribution of sector-specific emissions to observed levels of air pollutants at urban monitoring stations.

- Article

(13349 KB) - Full-text XML

- Companion paper

-

Supplement

(919 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Air quality (AQ) modelling plays an important role by assessing the air pollution situation in urban areas and by supporting the development of guidelines for efficient air quality planning, as highlighted in the current Air Quality Directive (AQD) of the European Commission (EC, 2008). The main air pollution issues in European cities are the human health impacts of exposure to particulate matter (PM), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and ozone (O3), while the effects of air pollution due to sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO), lead (Pb) and benzene have been reduced during the last 2 decades due to emission abatement measures. Tropospheric (ground-level) ozone is a secondary pollutant generated in in photochemical reaction cycles involving two classes of precursor compounds, i.e. nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), initiated by the reaction of the hydroxyl (OH) radical with organic molecules. For health protection, a maximum daily 8 h mean threshold for ozone (120 µg m−3) is specified as a target value in the European Union, which should not be exceeded at any AQ monitoring station on more than 25 d yr−1. However, about 15 % of the population living in urban areas is exposed to ozone concentrations above the European Union (EU) target value (EEA, 2015). Traffic is a major source of nitrogen oxides () and highly contributes to the population exposure to ambient NO2 concentrations in urban areas because these emissions occur close to the ground and are distributed across densely populated areas. Urban emissions of ozone precursors are transported by local and/or regional air mass flows towards suburban and rural areas, which can be impacted by O3 pollution episodes (Querol et al., 2016).

Eulerian chemistry-transport model (CTM) systems using numerical methods for solving photochemistry (including chemical reaction schemes with varying degrees of detail) have mainly been used for regional-scale air quality studies. Recent nested model approaches using regional CTM systems have been applied to capture pollution processes from the continental scale to the local scale using between 1 and 5 km resolution and a temporal resolution of 1 h for the innermost domain (e.g. Borge et al., 2014; Karl et al., 2015; Petetin et al., 2015; Valverde et al., 2016). Regional AQ models can give a reliable representation of O3 concentrations in the urban background, but due to their limitation in resolving the near-field dispersion of emission sources and photochemistry at the sub-kilometre scale, i.e. in street canyons, around industrial stacks and on the neighbourhood level, they cannot provide the information needed by urban policymakers for population exposure mapping, city planning and the assessment of abatement measures.

Urban-scale AQ models overcome the limitation inherent in regional-scale models by taking into account details of the urban topography, wind flow field characteristics, land use information and the geometry of local pollution sources. The urban AQ model EPISODE developed at the Norwegian Institute for Air Research (NILU) is a 3-D Eulerian grid model that operates as a CTM, offline coupled with a numerical weather prediction (NWP) model. EPISODE is typically applied with a horizontal resolution of 1 × 1 km2 over an entire city with domains of up to 2500 km2 in size. The Eulerian grid component of EPISODE simulates advection, vertical and/or horizontal diffusion, background transport across the model domain boundaries, and photochemistry. Several sub-grid-scale modules are embedded in EPISODE to represent emissions (line source and point sources), Gaussian dispersion and local photochemistry. In particular, the model allows the user to retrieve concentrations at the sub-grid scale in specified locations of the urban area. Moreover, the EPISODE model is an integral part of the operational Air Quality Information System AirQUIS 2006 (Slørdal et al., 2008).

Part one (Hamer et al., 2019) of this two-part article series provides a detailed description of the EPISODE model system, including the physical processes for atmospheric pollutant transport, the photo-stationary-state (PSS) approximation, the involvement of nitric oxide (NO), NO2 and O3, sub-grid components, and the interaction between the Eulerian grid and the sub-grid processing of pollutant concentrations. Part one examines the application of EPISODE to air quality scenarios in the Nordic winter setting. During wintertime in northern Europe, the PSS assumption is a rather good approximation of the photochemical conversion occurring close to the emission sources. However, when the solar ultraviolet (UV) radiation is stronger, in particular during summer months or at more southerly locations, net ozone formation may take place in urban areas at a certain distance from the main local emission sources (Baklanov et al., 2007). EPISODE in its routine application does not allow for the treatment of photochemistry involving VOCs and other reactive gases leading to the photochemical formation of ozone.

In this part, the features of the CityChem extension for treating the complex atmospheric chemistry in urban areas and specific developments within the sub-grid components for a more accurate representation of near-field dispersion in proximity to urban emission sources are described. Atmospheric chemistry on an urban scale is complex due to the large spatial variations of input from anthropogenic emissions. VOCs related to emissions from traffic are involved in chemical conversion in urban areas. Therefore, it has become necessary to simulate a large number of chemical interactions involving NOx, O3, VOCs, SO2 and secondary pollutants. In order to use comprehensive photochemical schemes in urban AQ models involving VOC interactions, the highest priority for the initial development was to reduce the number of compounds and reactions to a minimum, while maintaining the essential and most important aspects of chemical reactions taking place in the urban atmosphere on the relevant space scales and timescales.

CityChem offers a more advanced treatment for the photochemistry of multiple gaseous pollutants on the Eulerian grid, as well as for dispersion close to point emission sources (e.g. industrial stacks) and line emission sources (open roads and streets).

-

Photochemistry on the Eulerian grid uses a numerical chemistry solver. The available chemistry schemes include (1) EMEP45 (Walker et al., 2003), which resulted from an appropriate reduction of the former EMEP (European Monitoring and Evaluation Programme) chemistry scheme (Simpson, 1995); (2) EmChem03-mod, with updated reaction equations and coefficients compared to EMEP45; (3) and EmChem09-mod, which is similar to the current EMEP chemistry mechanism (EmChem09; Simpson et al., 2012). EmChem09-mod enables the simulation of biogenic VOCs, such as isoprene and monoterpenes, emitted from urban vegetation.

-

Modifications of the photochemistry in the sub-grid components have replaced the PSS assumption with the EP10-Plume scheme, a compact scheme including inorganic reactions and the photochemical degradation of formaldehyde, using a numerical solver.

-

Modifications of the line source emission model have been made to compute receptor point concentrations in street canyons. A simplified street canyon model (SSCM) is implemented to account for pollutant transfer along streets, including a parameterization of mass transfer within a simplified building geometry at street level.

-

Modifications to the plume rise from elevated point sources allow for a more accurate computation of the plume trajectories. The Meteorological Pre-Processor (WMPP) of the Weak-wind Open Road Model (WORM) is utilized in the CityChem extension to calculate the wind speed at plume height.

Although computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models can be used to solve for local-scale phenomena along point and line emission sources, they are limited to localized applications and are not appropriate for the simulation of dispersion across complex urban areas. In addition, the simulation of the chemical conversions of reactive pollutants using CFD models requires a large amount of computational time (Sanchez et al., 2016).

The EPISODE–CityChem model, which is based on the core of the EPISODE model, integrates the CityChem extension into an urban CTM system. This paper gives a model description of EPISODE–CityChem version 1.2. In the typical setup, EPISODE–CityChem uses downscaled meteorological fields generated by the meteorological component of the coupled meteorology–chemistry model TAPM (The Air Pollution Model; Hurley, 2008; Hurley et al., 2005). TAPM is a prognostic model which uses the complete equations governing the behaviour of the atmosphere and the dispersion of air pollutants. EPISODE–CityChem is coupled offline with the regional-scale air quality model CMAQ (Community Multiscale Air Quality; Byun et al., 1999; Byun and Schere, 2006; Appel et al., 2013) using hourly varying pollutant concentrations at the lateral and vertical boundaries from CMAQ as initial and boundary concentrations.

EPISODE–CityChem has the capability to simulate the photochemical transformation of multiple reactive pollutants along with atmospheric diffusion to produce concentration fields for the entire city on a horizontal resolution of 100 m or even finer and a vertical resolution of 24 layers up to 4000 m of height. The possibility to get a complete picture of the urban area with respect to reactive pollutant concentrations, but also information enabling exposure calculations in highly populated areas close to road traffic line sources and industrial point sources with high spatial resolution, turns EPISODE–CityChem into a valuable tool for urban air quality studies, health risk assessment, sensitivity analysis of sector-specific emissions, and the assessment of local and regional emission abatement policy options.

The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 gives an overview of EPISODE–CityChem and a detailed description of the photochemical reaction schemes and modifications of near-source dispersion in the sub-grid components. Section 3 presents tests of the various modules in the CityChem extension. Section 4 describes the application of EPISODE–CityChem within a nested model chain for simulating the air quality and atmospheric chemistry in the city of Hamburg. We assess the performance of EPISODE–CityChem in reproducing the temporal and spatial variation of air pollutant concentrations against data from urban monitoring stations. Model results from EPISODE–CityChem are compared (1) to results from the standard EPISODE model to quantify the total effect of the new implementations and (2) to results from TAPM, acting as reference model for air pollution modelling on the urban scale. Section 5 outlines plans for the future development of the EPISODE–CityChem model, addressing the need for more sophisticated photochemistry, treatment of aerosol formation on an urban scale and further improvements of the source dispersion. A list of acronyms and abbreviations used in this work is given in Appendix A.

EPISODE consists of a 3-D Eulerian grid CTM that interacts with a sub-grid Gaussian dispersion model for the dispersion of pollutants emitted from both line and point sources. We refer to part one (Hamer et al., 2019) for a technical description of the model. The standard EPISODE model simulates the emission and transport of NOx, as well as fine particulate matter with PM2.5 (particles with diameter less than 2.5 µm) and PM10 (particles with diameter less than 10 µm) in urban areas, with the specific aim of predicting concentrations of NO2, which is the major pollutant in many cities of northern Europe.

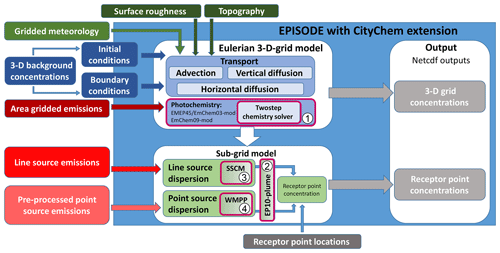

Figure 1Schematic diagram of the EPISODE model with the CityChem extension (EPISODE–CityChem model). The large blue box represents operations carried out during the execution of the EPISODE model. The components of the EPISODE model are the Eulerian grid model and the sub-grid models. The inputs for EPISODE are specified on the periphery. Modules belonging to the CityChem extension are shown with a magenta frame and are numbered: (1) photochemistry on the Eulerian grid, (2) EP10-Plume chemistry in the sub-grid components, (3) simplified street canyon model (SSCM) in the line source sub-grid model and (4) WORM Meteorological Pre-Processor (WMPP) in the point source sub-grid model.

EPISODE–CityChem solves the photochemistry of multiple reactive pollutants on the Eulerian grid by using one of the following chemical schemes: (1) EMEP45 chemistry, (2) EmChem03-mod or (3) the EmChem09-mod. In the sub-grid components, the PSS assumption involving is replaced by the EP10-Plume scheme. Dispersion close to point and line sources is modified in the sub-grid component. In the line source sub-grid model, the simplified street canyon model (SSCM) is integrated to calculate pollutant dispersion in street canyons. In the point source sub-grid model the WMPP (WORM Meteorological Pre-Processor) is integrated to calculate the wind speed at plume height. Figure 1 illustrates the modules and processes of the EPISODE model with the CityChem extension. Modules that belong to the CityChem extension are shown in boxes with a magenta frame.

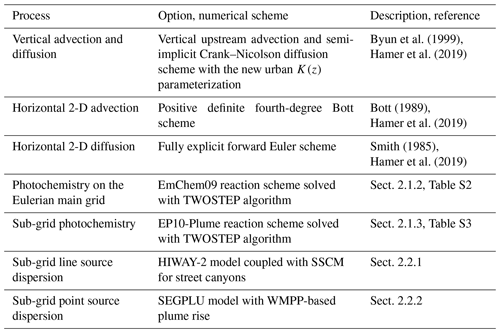

Byun et al. (1999)Hamer et al. (2019)Bott (1989)Hamer et al. (2019)Smith (1985)Hamer et al. (2019)The recommended configuration of model processes in EPISODE–CityChem is given in Table 1. EPISODE–CityChem has been used with this configuration to simulate the air quality and atmospheric chemistry in the city of Hamburg (Sect. 4).

In EPISODE–CityChem, a regular receptor grid is defined, for which time-dependent surface concentrations of the pollutants at receptor points are calculated by summation of the Eulerian grid concentration of the corresponding grid cell (i.e. the background concentration) and the concentration contributions from the Gaussian sub-grid models due to line source and point source emissions. This way, surface concentration fields of pollutants for the entire city at a horizontal resolution of (currently) 100 m are obtained. The modules of the CityChem extension for photochemistry and source dispersion are described in detail in the remainder of this section.

2.1 Extensions to the photochemistry

Atmospheric gas-phase chemical reactions are described by ordinary differential equations (ODEs). The ODE set of reactions is considered stiff because the chemical e-folding lifetimes of individual gases vary by many orders of magnitude in the urban atmosphere (from approx. 10−6 to 106 s−1; McRae et al., 1982). The non-linear system of the stiff chemical ODEs is solved by the TWOSTEP solver (Verwer and Simpson, 1995; Verwer et al., 1996) using fast Gauss–Seidel iterative techniques, with numerical error control and restart in the case of detected numerical inaccuracies (Walker et al., 2003). The solver is applied to chemical reaction mechanisms available in EPISODE–CityChem for photochemical transformation on the Eulerian grid (EMEP45, EmChem03-mod and EmChem09-mod) and in the sub-grid component (EP10-Plume). For solving the EMEP45 scheme, the Gauss–Seidel iterative technique is used for all compounds except for the oxygen atoms and OH, for which reactions are very fast and we use the steady-state approximation instead (Walker et al., 2003). The relative error tolerances for the solver are set to 0.1 (10 % relative error) for all chemical compounds, while the absolute error tolerances are set in a range from 2.5×108 molecule cm−3 to 1.0×1015 molecule cm−3 depending on the compound. Photodissociation rates are specified as a function of the solar zenith angle and cloud cover, as given in Appendix B. The sink terms for the dry deposition and wet removal of gases and particles are presented in Appendix C.

2.1.1 Development and description of the EMEP45 chemistry scheme

The EMEP45 chemistry scheme developed at NILU (Walker et al., 2003) contains 45 chemical compounds and about 70 chemical reactions compared to 70 compounds and about 140 reactions in the original EMEP mechanism (Simpson, 1992, 1993; Andersson-Sköld and Simpson, 1999).

The intention of the development of EMEP45 was to obtain a condensed chemical scheme for urban areas that still captures the key aspects of the photochemistry in the urban atmosphere. The reduction of the EMEP mechanism was guided by the following considerations: first, the new chemistry scheme is applied in rather polluted urban regions. Second, the residence time of the atmospheric compounds in the urban domain is normally limited to less than a day.

The main simplification in EMEP45 compared to the original EMEP mechanism is the neglect of peroxy radical self-reactions. The self-reactions of peroxy radicals, either between the organic peroxy radical (RO2) and hydroperoxyl radical (HO2) or between two organic peroxy radicals,

are in competition with the reaction of RO2 (or HO2) with NO, leading to photochemical ozone formation:

At the ambient levels of NOx typical of moderately or more polluted areas, Reactions (R1)–(R3) will be negligible compared with Reaction (R4). Thus, all reactions of organic peroxy radicals of type (R2) and (R3) were omitted in the EMEP45 scheme. However, due to their relevance, the reaction of HO2 with the methyl peroxy radical (CH3O2) and the HO2 self-reaction (R1) were included. EMEP45 includes a simple four-reaction scheme for the oxidation of isoprene (C5H8) with the OH radical. All reaction rates and coefficients in EMEP45 are according to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) 2001 recommendations (Atkinson et al., 2000).

2.1.2 Development of the EmChem03-mod scheme and the EmChem09-mod scheme

The EMEP45 scheme was updated in recent years at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht (HZG). All reaction rate constants were updated in accordance with the default chemistry scheme EmChem09 of the EMEP/MSC-W model (Simpson et al., 2012). The resulting scheme is called EmChem03-mod and consists of 45 gas-phase species, 51 thermal reactions and 16 photolysis reactions, as listed in Table S1 in the Supplement. The most important technical change compared to EMEP45 is that the new scheme can be dynamically updated and further extended with new chemical reactions and compounds. The chemical preprocessor of the EMEP/MSC-W model, GenChem, developed at the EMEP group (Simpson et al., 2012), is used to convert lists of input chemical species and reactions to differential equations of the solver in Fortran 90 code. This makes the update and extension of the new scheme entirely flexible.

In the next step, the EmChem09-mod scheme (Table S2) was developed based on the current EMEP chemistry mechanism, EmChem09 (Simpson et al., 2012), by (1) replacing the detailed isoprene chemistry with the simplified isoprene reaction scheme from EMEP45, (2) adding monoterpene oxidation reactions and (3) including semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) as reaction products which can potentially act as precursors for secondary organic aerosol (SOA) constituents.

EmChem09-mod includes reactions between organic peroxy radicals and HO2 as well as other organic peroxy radicals; it is therefore appropriate for low NOx conditions in rural and suburban areas of the city domain. With EmChem09-mod the chemistry of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs), emitted from urban vegetation, can be simulated. Two monoterpenes, α-pinene and limonene, are model surrogates to represent slower- and faster-reacting monoterpenes (α-pinene: cm3 s molecule−1; limonene: cm3 s molecule−1; for the OH-reaction, both at 298 K). The scheme considers the OH-initiated oxidation of isoprene, as well as the oxidation of α-pinene and limonene by OH, NO3 and O3. Limonene has two reactive sites (double bonds) allowing for a rapid reaction chain to oxidation products with low vapour pressure. The lumped reaction scheme of α-pinene is adopted from Bergström et al. (2012) and that of limonene is based on Calvert et al. (2000). In total, EmChem09-mod includes 70 compounds, 67 thermal reactions and 25 photolysis reactions.

2.1.3 Development and description of the EP10-Plume chemistry scheme

In the sub-grid components, i.e. the Gaussian models for line and point source dispersion, the PSS assumption involving was replaced by the EP10-Plume scheme for computation of the chemistry at the local receptor grid points. EP10-Plume includes only the reactions of O3, NO, NO2, nitric acid (HNO3) and CO, as well as the photochemical oxidation of formaldehyde (HCHO). It contains 10 compounds and 17 reactions; Table S3 provides a list.

Only a small portion of NOx from motor vehicles and combustion sources is in the form of NO2, the main part being NO. The largest fraction of ambient NO2 originates from the subsequent chemical oxidation of NO. The only reactions considered to be relevant in the vicinity of NOx emission sources are

For conditions in northern Europe, an instantaneous equilibrium between the three reactions relating NO, NO2 and O3 is assumed, the so-called PSS, and implemented in the EPISODE model. In EP10-Plume the three reactions are, however, treated explicitly. Reactions occurring with negligible rates at the NOx levels typical of moderately or highly polluted areas were excluded from the scheme. HCHO and acetaldehyde are important constituents of vehicle exhaust gas (e.g. Rodrigues et al., 2012). The photolysis of HCHO is a source of HO2 radicals.

HCHO also reacts with the OH radical to give two HO2 radicals. HO2 competes with ozone for the available NO (Reaction R4), and the reaction between HO2 and NO results in additional NO-to-NO2 conversion. Since the generation of HO2 radicals through HCHO photolysis does not depend on the entrainment of photo-oxidants from the background air, it can trigger the photochemical reaction cycle even in traffic plumes very close to the source. Carbon monoxide (CO) has a lifetime of about 2 months towards OH (at molecules cm−3). Reaction (R10) is therefore not relevant near sources and of very low relevance on the urban scale. For completeness of the OH-to-HO2 cycling, Reaction (R10) was, however, included in EP10-Plume.

2.2 Extensions to the source dispersion

Sub-grid models to resolve dispersion close to point sources and line sources are embedded in the EPISODE model to account for sub-grid variations as a result of emissions along open roads and streets as well as along plume trajectories from elevated point source releases. The sub-grid model for line sources, i.e. open road and urban street traffic, is the Gaussian model HIWAY-2 (Highway Air Pollution Model 2; Petersen, 1980) from the U.S. EPA with modifications. The sub-grid model for point sources, e.g. stacks of industrial plants and power plants, is the Gaussian segmented plume trajectory model SEGPLU (Walker and Grønskei, 1992). SEGPLU computes and keeps a record of subsequent positions of plume segments released from a point source and the corresponding pollutant concentration within each plume segment. The vertical position of the plume segment is calculated from the plume rise of the respective point source. Plume rise for elevated point sources due to momentum or buoyancy is computed based on the plume rise equations originally presented by Briggs (1969, 1971, 1975). A detailed description of the implementation of HIWAY-2 and SEGPLU in the EPISODE model is given in part one (Hamer et al., 2019). In this section, extensions of the sub-grid models for the simulation of dispersion near sources within CityChem are described.

2.2.1 Implementation of a simplified street canyon model (SSCM) for line source dispersion

In CityChem, a simplified street canyon model (SSCM) to compute concentrations for receptor points that are located in street canyons is introduced. The street canyon model follows in most aspects the Operational Street Pollution Model (OSPM; Berkowicz et al., 1997). A fundamental assumption of this model is that when the wind blows over a rooftop in a street canyon, an hourly averaged recirculation vortex is always formed inside the canyon (Hertel and Berkowicz, 1989). The part of the street canyon covered by the vortex of recirculating air is called the recirculation zone.

The concentration at a receptor point located within an urban street canyon is calculated as the sum of the concentration contribution (Cline,s) due to the emissions of the line source s and the urban background concentration, which is taken from the corresponding cell of the Eulerian grid component. The contribution of a line source s is given by the direct contribution (Cscdir,s) from the traffic plume plus a contribution from the recirculation of the traffic plume (Cscrec,s) due to the vortex inside the canyon (Berkowicz et al., 1997):

The leeward receptor inside a street canyon is exposed to direct contribution from the emissions inside the recirculation zone (unless the wind direction is close to parallel) and a recirculation contribution. For the receptor on the windward side, only emissions outside the recirculation zone are considered for the direct contribution. If the recirculation zone extends through the whole canyon, no direct contribution is given to the windward receptor. The length of the recirculation zone, Lrec, is estimated as being twice the average building height of the canyon and limited by the canyon width, Wsc.

The calculation of the direct and recirculation concentration contributions in this simple approach is adopted from the OSPM following the description in Berkowicz et al. (1997) with certain modifications. Simplifications are made with respect to the street canyon geometry, since only general geometries with average street canyon width and height are used. The rate of release Qs in the street assumes that emissions are distributed homogeneously along the line source segment that is inside the street canyon area, which means emissions are assumed to be distributed homogeneously over the street canyon in the full length and width of the canyon (along the dimension of the respective line source object).

The direct contribution is calculated using a Gaussian plume model. The direct concentration contribution at the receptor point Cscdir,s, located at distance x from the line source (i.e. starting from the midline of the street), is obtained by integrating along the wind path at street level. The integration path depends on wind direction, the extension of the recirculation zone and the street canyon length (Hertel and Berkowicz, 1989):

where h0 is a constant that accounts for the height of the initial pollutant dispersion (h0=2 m is used in SSCM), σw is the vertical velocity fluctuation due to mechanical turbulence generated by wind and vehicle traffic in the street, and ustreet is the wind speed at street level, calculated assuming a logarithmic reduction of the wind speed at rooftop towards the bottom of the street. Note that the wind direction at street level in the recirculation zone is mirrored compared to the roof-level wind direction. Outside the recirculation zone, the wind direction is the same as at roof level. The vertical velocity fluctuation is calculated as a function of the street-level wind speed and the traffic-produced turbulence by the following relationship (Berkowicz et al., 1997):

where αs is a proportionality constant empirically assigned a value of 0.1, and σw0 is the traffic-induced turbulence, in SSCM assigned a value of 0.25 m s−1, which is typical for traffic on working days between 08:00 and 19:00 (Central European Time) in situations in which traffic-induced turbulence dominates (Kastner-Klein et al., 2000; Fig. 6 therein).

The integration path for Eq. (2) begins from xstart, which is defined as the distance from the receptor point at which the plume has the same height as the receptor, which is zero in the case that h0 is smaller than or equal to the height of the receptor. The upper integration limit is xend, defined by tabular values in Ottosen et al. (2015, Table 3 therein). The integration is performed along a straight line path against the wind direction. The calculation of the maximum integration path, Lmax, depends on the wind direction with respect to the street axis, θstreet, i.e. the angle between the street and the street-level wind direction (Ottosen et al., 2015).

The recirculation contribution is computed using a simple box model, assuming equality of the inflow and outflow of the pollutant. The cross section of the recirculation zone is modelled as a trapezium with upper length Ltop and baseline length Lbase. Ltop is half of the baseline length, where Lbase is defined as . The length of the hypotenuse of the trapezium is calculated as , assuming the leeward side edge of the recirculation zone to be the vertical building wall, with the length of the building height. It is further assumed that the slant edge of the recirculation zone towards the opposite street side is not intercepted by buildings.

The recirculation concentration contribution is expressed by the relationship (Berkowicz et al., 1997)

where σwt is the ventilation velocity of the canyon as given by Hertel and Berkowicz (1989), and σhyp is the average turbulence at the hypotenuse of the trapezium (slant edge towards the opposite street side).

For a given receptor point, the concentration contribution from a line source is calculated either by HIWAY-2 or by SSCM. HIWAY-2 does not calculate line source concentration contributions to receptors that are upwind of a line source or receptor points that are very close to the line source. For all windward and leeward receptor points (1) located within a model grid cell defined as a street canyon cell (see below), (2) located close enough to a line source (i.e. within the actual street canyon) and (3) located at a road link with length >8 m, the concentration contribution from the street is calculated by SSCM. For all windward receptors which do not fulfil these conditions, the concentration contribution is calculated by HIWAY-2.

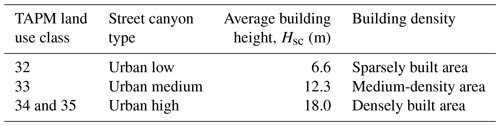

The complex and diverse geometry of street canyons is approximated by three generic types for which average street canyon geometry properties are applied (Table 2). Street canyons are identified based on the urban land use classes of TAPM. Each line source for which the geometric midpoint is located in a grid cell with urban land use (land use classes 32–35 defined in TAPM) is identified as a potential street canyon. A disadvantage of this method is that some streets and roads, especially in the sparsely built urban areas outside the inner city, will be classified as street canyons despite being open roads with open spaces between buildings.

Table 2The geometry of three generic street canyon types in CityChem. For street canyons of type “urban medium”, Hsc is taken as the mean value of “urban low” and “urban high”.

Furthermore, it is assumed that all buildings at the street canyon line source have the same average building height, Hsc, and that there are no gaps between the buildings. The average building heights for the TAPM land use classes were obtained by the intersection of the 3-D city model LoD1-DE Hamburg (LGV, 2014) – which contains individual building heights – with the CORINE (Coordination of Information on the Environment) urban land use information (CLC, 2012). The width of the street canyon, Wsc, is defined as twice the width of the (line source) street width W to account for sidewalks and to avoid canyons that are too narrow. The length of the street canyon, Lsc, corresponds to the length of the line source within the grid cell.

2.2.2 Implementation of the WMPP for point sources

The wind speed profile function of the meteorological preprocessor WMPP is utilized in the CityChem extension to calculate the wind speed at plume height within the point source sub-grid dispersion model. WMPP replaces the previous routine, which calculated the wind speed at plume height using a logarithmic wind speed profile corrected by the stability function for momentum based on Holtslag and de Bruin (1998). WMPP has been developed as part of NILU's WORM open-road line source model (Walker, 2011, 2010) to calculate various meteorological parameters needed by WORM. In the current version of WORM, the profile method is applied using hourly observations of wind speed at one height, e.g. 10 m, and the temperature difference between two heights, e.g. 10 and 2 m, to calculate the other derived meteorological parameters.

Given the above input data and an estimate of the momentum surface roughness, WMPP calculates friction velocity (u∗), temperature scale (θ∗) and inverse Obukhov length (L−1) according to Monin–Obukhov similarity theory. These quantities are calculated by solving the following three non-linear equations:

where κ is Von Kármán's constant (0.41), g is the acceleration of gravity (9.81 m s−2), Δu is the wind speed difference between heights zu2 and zu1, where zu2 is e.g. 10 m, and zu1=z0m, where the wind speed is zero, so that . In the definition of the temperature scale, Δθ is the difference in potential temperature between heights zt2 and zt1, which are e.g. 10 and 2 m, respectively, so that we have , where the +0.01 term is for the conversion from potential temperature to actual temperature. In the definition of the Obukhov length, Tref is a reference temperature, here taken to be the average of T2 m and T10 m.

In Eq. (5), the similarity functions φm and φh are defined as follows (Högström, 1996):

and

where Pr0=0.95 is the Prandtl number for neutral conditions and where the empirical coefficients are defined as , , βm=5.3 and βh=8.2.

This set of similarity functions is then used to calculate vertical profiles of temperature and wind speed. The temperature at a height (in metres above the ground) is thus calculated by

where zref=10 m and cp is the specific heat capacity of air, here set to 1005 J kg−1 K−1. Similarly, the wind speed at height z (m) above the ground is calculated by

In CityChem, WMPP is used in the sub-grid point source model to calculate the wind speed at plume height according to Eq. (9). WMPP can also be used to calculate the convective velocity scale w∗ and the mixing height hmix, but this is not implemented in CityChem.

2.3 Additional modifications

Here we describe the modifications in the CityChem extension to read hourly 3-D boundary concentrations from the output of the CMAQ model and to determine sub-grid concentrations from a regular receptor grid in the surface model layer.

2.3.1 Adapting 3-D boundary conditions from the CMAQ model

CityChem has the option to use the time-varying 3-D concentration field at the lateral and vertical boundaries from the CMAQ model as initial and boundary concentrations for selected chemical species. The adaption of boundary conditions from CMAQ output in the EPISODE model is based on the implementation for boundary conditions from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS; http://www.regional.atmosphere.copernicus.eu/, last access: 29 July 2019) described in part one (Hamer et al., 2019). The regional background concentrations are adopted for the grid cells (outside the computational domain) directly adjacent to the boundary grid cells of the model domain and for the vertical model layer that is on top of the highest model layer. The outside grid cell directly adjacent to the boundary grid cell is filled with the CMAQ concentration value for inflow conditions and with the concentration value of the boundary grid cell for outflow conditions, i.e. allowing for a zero-concentration gradient at the outflow boundary. More details on the treatment of 3-D boundary conditions are given in Appendix D.

2.3.2 Description of the regular receptor grid

In the CityChem extension, a regular receptor grid is defined, for which time-dependent surface concentrations of the pollutants at receptor points are calculated by summation of the Eulerian grid concentration of the corresponding grid cell (i.e. the background concentration) and the concentration contributions from the sub-grid models due to the dispersion of line source and point source emissions. Regular receptor grids with a typical resolution of 100 × 100 m2 have also been used in earlier versions of EPISODE, but primarily for capturing sub-grid-scale concentration contributions from larger industrial point sources. The establishment of a regular receptor grid is an integral part of CityChem to enable the higher-resolution output required for comparison with monitor data acquired near line sources. Line sources are a major source of pollutant emissions affecting inner-city air quality; thus, the use of the regular receptor grid provides information at much higher spatial resolution than the Eulerian grid output alone. The regular receptor grid in EPISODE–CityChem differs from the downscaling approach by Denby et al. (2014), which allocates sampling points at high density along roads and other line sources but much fewer further away from the line sources. While Denby et al. (2014) interpolate the model-computed high-density set of receptor concentrations to the desired output resolution using ordinary kriging, EPISODE–CityChem gives as output the receptor point concentrations on a regular 2-D grid covering the entire model domain.

The instantaneous concentration Crec in an individual receptor point r∗ of the receptor grid with coordinates (xr, yr, zr) is defined as

where Cm is the main grid concentration of the grid cell (x, y, 1) in which the receptor point is located. The grid (background) concentration Cm used in Eq. (10) corresponds to a modified Eulerian 3-D grid concentration, i.e. , to prevent emissions of point and lines sources from being counted twice. Cpoint,p is the instantaneous concentration contribution of point source p calculated by the point source sub-grid model, and Cline,s is the instantaneous concentration contribution of line source s calculated by the line source sub-grid model. Since Crec is not added to the main grid concentration but kept as a separate (diagnostic) variable, the double-counting of emitted pollutant mass is prevented. In the CityChem extension, receptor point concentrations represent the high-resolution ground concentration of a cell with the grid cell area of the receptor grid.

On the 3-D Eulerian grid, time-dependent concentration fields of the pollutants are calculated by solving the advection–diffusion equation with terms for chemical reactions, dry and wet deposition, and area emissions. The hourly 2-D and 3-D fields of meteorological variables and the hourly 2-D fields of area emissions are given as input to the model with the spatial resolution of the Eulerian grid. As the model steps forward in time, an accurate account of the total pollutant mass from the area, point and line sources is kept within the Eulerian grid model component. Emissions from line sources are added to the Eulerian grid concentrations at each model time step.

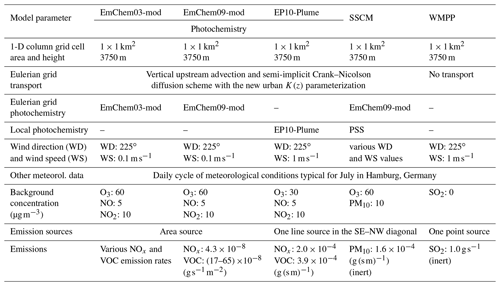

For the test of the various model extensions, EPISODE was run as a 1-D column model, with vertical exchange as the only transport process. Emissions were injected into the ground cell (grid centre at UTM coordinates: (X) 568500, (Y) 5935550, 32 N) with an area of 1 × 1 km2 and flat terrain (15 m a.s.l.). Table 3 shows the general setup for the 1-D column and the specific configuration for the tests. Mixing height, surface roughness and friction velocity were kept constant (hmix=250m, z0=0.8 m s−1, m s−1). Hourly varying meteorological variables included air temperature, temperature gradient, relative humidity, sensible and latent heat fluxes, total solar radiation, and cloud fraction. The test simulations are performed for a period of 5 d, and results were taken as an average of the period.

3.1 Test of the photochemistry on the Eulerian grid

3.1.1 Tests of the original EMEP45 photochemistry

When the condensed EMEP45 photochemistry was developed, various tests were carried out to compare the condensed mechanism with the standard EMEP chemical mechanism. Results from box model studies with the two chemical mechanisms revealed that there were generally small differences between the full and the condensed chemical mechanisms. Even for conditions more representative of a rural environment, the difference between the standard EMEP and the condensed mechanism was small. For these more rural conditions, the condensed mechanism gave slightly lower levels of NO and NO2, while the ozone concentration was almost identical in the two mechanisms. For urban conditions, these differences were expected to be significantly smaller.

The EPISODE model with the condensed EMEP45 mechanism furthermore participated in the CityDelta project (Cuvelier et al., 2007) within which it was applied to the city of Berlin. CityDelta was the first in a series of projects (later named EuroDelta) dedicated to photochemical model inter-comparisons. When evaluated against observations of NO2 and O3, the EPISODE model with the EMEP45 chemistry performed favourably when compared to the suite of atmospheric models participating in the CityDelta project (Walker et al., 2003).

3.1.2 Test of ozone formation with EmChem03-mod

The ozone–NOx–VOC sensitivity of the EmChem03-mod scheme in the Eulerian model component was analysed by repeated runs with varying emissions of NOx and non-methane VOCs (NMVOCs) using the daily cycle of mean summer meteorology with clear sky but low wind speed (0.1 m s−1). The ozone net production in the runs was taken at the maximum daily O3 during the simulation.

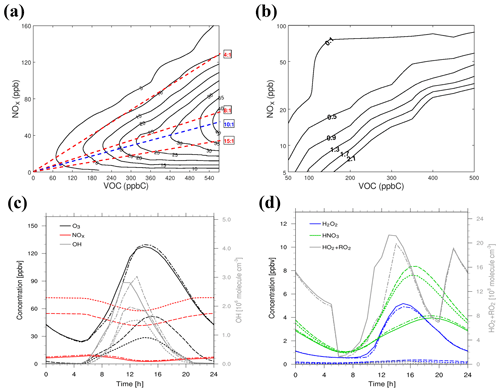

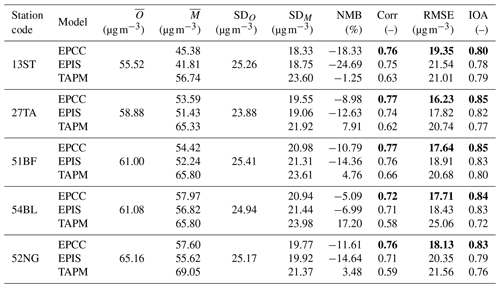

Figure 2Test of relationships between ozone, NOx and NMVOCs in EmChem03-mod: (a) ozone isopleth diagram, (b) isopleth diagram showing the ratio of the production rate of peroxides to the production rate of nitric acid, (c) concentration time series of O3 (black), NOx (red) and OH (grey; second y axis), and (d) concentration time series of H2O2 (blue), HNO3 (green) and HO2+RO2 concentration (grey, second y axis). Daily concentration cycle as an average from a test run with NMVOC emissions of and varying NOx emissions: (solid lines), (dash-dotted lines), (dashed lines) and (dotted lines). Lines of constant VOC∕NOx ratio are annotated with red dashed lines (4 : 1, 8 : 1 and 15 : 1) and the blue dashed line (10 : 1) in panel (a). Note the logarithmic scale of the y axis in panel (b).

An area source of traffic emissions of NOx and NMVOCs in the ground cell of the 1-D column was activated in the test. The variation of ozone precursor emissions from the traffic area source was done in a systematic way in order to derive the ozone isopleth diagram (Fig. 2a), which shows the rate of O3 production (ppb h−1) as a function of NOx and NMVOC concentrations. Compound abundances are given in mixing ratios (ppb) for this test to enable comparison with the literature on ozone formation potentials.

The ozone–precursor relationship in urban environments is a consequence of the fundamental division into NOx-limited and VOC-limited chemical regimes. VOC∕NOx ratios are an important controlling factor for this division of chemical regimes (Sillman, 1999). VOC-limited chemistry generally occurs in urban centres where NO2 concentrations are high due to traffic emissions. Rural areas downwind of the city are typically NOx limited (Ehlers et al., 2016).

The “ridgeline” of the ozone isopleth diagram marks the local maxima of O3 production and differentiates two different photochemical regimes. Below the line is the NOx-limited regime, in which O3 increases with increasing NOx, while it is hardly affected by increasing VOCs. Above the line is the VOC-limited regime, in which O3 increases with increasing VOCs and decreases with increasing NOx. The ridgeline in Fig. 2a follows a line of constant VOC∕NOx ratio; in the case of EmChem03-mod it is close to the ratio 10 : 1, whereas a slope of 8 : 1 is more typically found (e.g. Dodge, 1977). The traffic NMVOC mixture includes a high share of aromatics (35 %) represented by o-xylene in the model. Due to the high reactivity of the NMVOC mixture, the ridgeline is tilted towards higher VOC∕NOx ratios compared to the ozone isopleths for a NMVOC mixture with lower reactivity.

The split into NOx-limited and VOC-limited regimes is closely associated with sources and sinks of odd hydrogen radicals (defined as the sum of OH, HO2 and RO2). Odd hydrogen radicals are produced in the photolysis of ozone and intermediate organics such as formaldehyde. Odd hydrogen radicals are removed by reactions that produce hydrogen peroxide (Reaction R1) and organic peroxides (Reaction R2). They are also removed by reaction with NO2, producing HNO3, according to

When peroxides represent the dominant sink for odd hydrogen, then the sum of peroxy radicals is insensitive to changes in NOx or VOC. This is the case for the concentrations represented as solid and dash-dotted lines in Fig. 2c–d. Doubling NOx emissions from solid lines to dash-dotted lines only marginally changes the peroxy radical sum concentration (Fig. 2d).

When HNO3 is the dominant sink of odd hydrogen, then the OH concentration is determined by equilibrium between the producing reactions (e.g. photolysis of O3) and the loss reaction (R11); it thus decreases with increasing NOx (Fig. 2c–d; from dashed to dotted lines), while it is either unaffected or increases due to the photolysis of intermediate organics with increasing VOCs.

Plotting the isopleths for the ratio of the production rate of peroxides to the production rate of HNO3 (Fig. 2b) shows that this ratio is closely related to the split between NOx-limited and VOC-limited regimes. The ratio is typically 0.9 or higher for NOx-limited conditions and 0.1 or less for VOC-limited conditions (Sillman, 1999). The ridgeline that separates the two regimes should be at a ratio of 0.5 (Sillman, 1999), which is the case in Fig. 2b. However, the curves representing the ratio are shifted towards higher NOx mixing ratios compared to the isopleth diagram for the ratio displayed in Sillman (1999, Fig. 8 therein). For instance, for 100 ppbC NMVOCs and 5 ppb NOx, the ratio is below 0.1 (VOC limited) in the isopleth diagram of Sillman (1999), while it is 1.3 (NOx limited) in Fig. 2b. The reason for this discrepancy is the lack of reactions producing organic peroxides (RO2H) in EmChem03-mod and thus the reduced removal of odd hydrogen in conditions with a high VOC∕NOx ratio. In conditions with NOx below 20 ppbv, EmChem03-mod has an efficiency of NO-to-NO2 conversion via Reaction (R4) that is too high.

3.1.3 Test of EmChem09-mod photochemistry

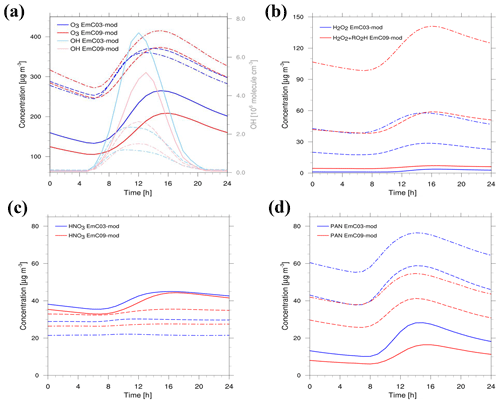

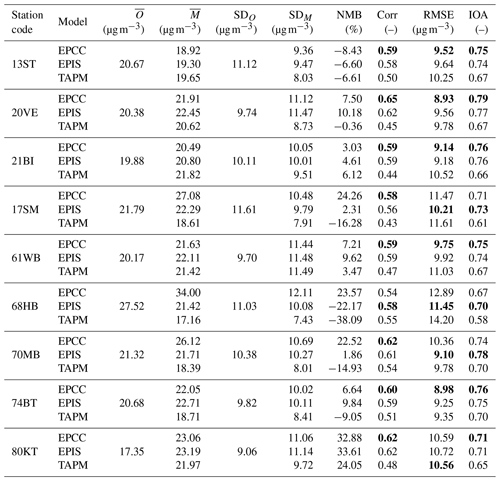

The EmChem09-mod scheme was compared to the EmChem03-mod scheme for conditions with relatively low levels of NOx (<20 µg m−3). The configuration of the test was the same as in Sect. 3.1.2, with an area source of traffic emissions of NOx (0.043 g s−1 in the 1 × 1 km2 ground cell) and varying emissions of NMVOC corresponding to VOC∕NOx ratios of 4 : 1, 8 : 1 and 15 : 1. The daily cycle of ozone with EmChem09-mod shows O3 concentrations which are lower for a VOC∕NOx ratio of 4 : 1 (VOC limited) than with EmChem03-mod, similar for a VOC∕NOx ratio of 8 : 1 (transition) to EmChem03-mod and higher for a VOC∕NOx ratio of 15 : 1 (NOx limited) than with EmChem03-mod (Fig. 3a). Compared to EmChem03-mod, the EmChem09-mod scheme includes reactions between organic peroxy radicals and HO2, as well as other organic peroxy radicals. In conditions with low levels of NOx, the rates from these reactions will be in competition with the reaction rates of organic peroxy radicals with NO.

Figure 3Comparison of EmChem09-mod (red lines) with EmChem03-mod (blue lines) for three different VOC∕NOx ratios: (a) O3 and OH (light colours, second y axis); (b) H2O2 and organic peroxides (abbreviated as RO2H); (c) HNO3; and (d) PAN. Daily concentration cycle as an average from a test run with NOx emissions of and NMVOC emissions corresponding to a VOC∕NOx ratio of 4 : 1 (solid lines), 8 : 1 (dashed lines) and 15 : 1 (dash-dotted lines).

The lower O3 with EmChem09-mod in VOC-limited conditions is related to the competition between organic peroxy radical self-reactions and the reaction with NO, preventing additional NO-to-NO2 conversion. Compared to EmChem03-mod, the removal of odd hydrogen through Reaction (R11) to form HNO3 is weakened (Fig. 3b), the formation of H2O2 and organic peroxides is enhanced (Fig. 3c), and the formation of peroxyacetyl nitrate (PAN) is suppressed (Fig. 3d); the latter is due to the competing reaction between the acetyl peroxy radical (CH3COO2) and HO2, which is not included in EmChem03-mod. As a result, less NO2 is lost and the NOx concentrations in EmChem09-mod increase compared to EmChem03-mod (Fig. S1), which reduces ozone production in the VOC-limited regime.

The higher O3 with EmChem09-mod in NOx-limited conditions is related to the much higher production of peroxides and the reduced production of PAN and HNO3 compared to EmChem03-mod. The NOx concentrations in EmChem09-mod are higher, which increases ozone production in the NOx-limited regime.

3.2 Test of EP10-Plume sub-grid photochemistry

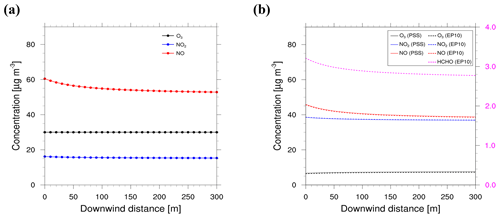

The photochemistry in the sub-grid component of EPISODE–CityChem was tested for dispersion from a single line source aligned in the SE–NW diagonal of the 1 × 1 km2 grid cell. The line source was oriented perpendicular to the wind direction, emitting NOx and NMVOCs with a ratio of 1 : 2. The HIWAY-2 line source model was used in the test (SSCM was not activated). Photochemistry tests were made as follows: (1) no chemistry; (2) photochemical steady-state assumption (PSS) for (default); and (3) with EP10-Plume using the numerical solver. Inside the centre cell, ground air concentrations downwind of the line source were recorded using additional receptor points every 10 m up to a distance of 300 m from the line source.

Figure 4Photochemistry downwind of a line source in the SE–NW diagonal of the 1 × 1 km2 grid cell: (a) concentration of O3 (black), NO (red), NO2 (blue) with no chemistry (lines with filled circles), and (b) O3, NO, NO2 and HCHO (magenta, second y axis) with PSS (solid lines) and EP10-Plume (dashed lines and magenta line). Note that lines for PSS and EP10-Plume are overlapping for O3, NO and NO2.

Comparing O3 (black lines), NO2 (red lines) and NO (blue lines) concentrations from the three tests with increasing downwind distance x shows that dilution alone (test with no chemistry; Fig. 4a) leads to a decay of NO, which follows a power function of the form , while O3 remains constant at the level of the background concentration (30 µg m−3).

Applying the PSS reduces O3 immediately at the line source by reaction (R5) to one-fourth of the concentration without chemistry. At the line source (0 m of distance), PSS converts roughly 15 µg m−3 NO to 21 µg m−3 NO2, as deduced from the differences between the no chemistry and the PSS test run. The third option, EP10-Plume, gives very similar results to PSS, with O3, NO and NO2 concentrations deviating by at most 4 % from the solution of the PSS (overlapping lines in Fig. 4b). In EP10-Plume, the line-emitted HCHO during daytime reacts with OH or undergoes photolysis to give HO2 radicals. However, the odd hydrogen radicals are rapidly removed by Reaction (R11), and the effect of emitted HCHO on O3 is negligible. It is noted that HCHO accounts for only 2.7 % of traffic NMVOC emissions. Further testing showed that the share of HCHO has to be increased by a factor of 10 or more (for the same VOC emission rate) in order to exceed the PSS concentration of O3 close to the line source.

3.3 Test of the source dispersion extensions

3.3.1 Test of SSCM for line source dispersion

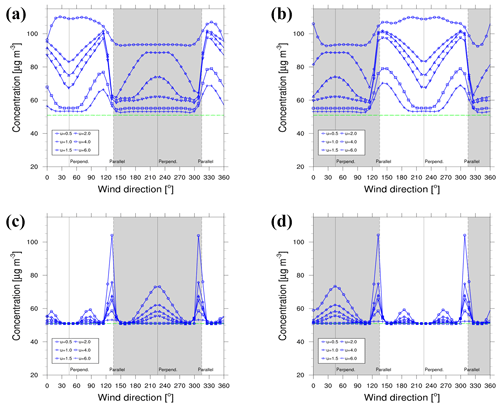

Tests with the simplified street canyon model (SSCM; see Sect. 2.2.1) were performed for different roof-level wind speeds (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 4.0 and 6.0 m s−1) and compared to results from the HIWAY-2 line source dispersion model. The street canyon was oriented along the SE–NW diagonal of the grid cell, canyon width was 18 m and average building height was 18 m, with no gaps between buildings. Receptor points were placed symmetrically on the northeast side and the southwest side of the canyon 5 m of distance from the street. Time-averaged modelled concentrations of PM10, emitted from the line source as a chemically inert tracer, are shown as a function of wind direction and wind speed in Fig. 5 for the northeast side (left) and southwest side (right) receptor. The wind direction dependency at the two receptors is simply shifted by 180∘ with respect to the other due to the symmetric arrangement. With SSCM, the leeward concentrations are generally higher than the windward concentrations (grey-shaded areas in the figure). For both models, maximum concentrations are calculated for wind direction close to parallel with the street (135 and 315∘).

Figure 5Test of the street canyon model: concentration of an inert tracer (PM10) at the northeast side receptor (a, c) and at the southwest side receptor (b, d) as a function of wind direction and wind speed (a, b) from a simulation with SSCM and (c, d) from a simulation with HIWAY-2 (no street canyon). The background concentration, taken from the grid cell at a maximum distance from the line, is shown as a green line. Wind speed (m s−1) is given in the legend. Grey-shaded area indicates when the station is on the windward side of the street canyon. The solid vertical line indicates wind perpendicular to the street, and the dashed vertical line indicates wind parallel to the street.

For this specific street canyon, with an aspect ratio (Wsc∕Hsc) equal to 1, the recirculation zone extends through the whole canyon at high wind speeds and the windward receptor only receives a contribution from the recirculation. At low wind speeds, here at 2 m s−1 or below, the windward side starts to receive a direct contribution because the extension of the vortex decreases at low wind speeds. At wind speeds below 0.5 m s−1, the vortex disappears and traffic-generated turbulence determines the concentration levels. Gaussian models are not designed to simulate dispersion in low-wind conditions. Therefore, a lower limit of the rooftop wind speed was placed at 0.5 m s−1 in this test, preventing the test of lower wind speeds. It is, however, obvious from Fig. 5a that the influence of the wind direction on concentrations at 0.5 m s−1 is much reduced compared to higher wind speeds.

Similar to SSCM, the simulation with HIWAY-2 shows a local maximum at the windward side when the wind is perpendicular to the street and a local minimum at the leeward side when the wind is perpendicular. In HIWAY-2, the pollution from traffic is dispersed freely away from the street because it applies to open road without buildings. In SSCM, the leeward side is influenced directly by the traffic emissions in the street and additionally by the recirculated polluted air. HIWAY-2 neglects the contribution of recirculated polluted air. This is also the reason why the baseline contribution (in addition to the urban background) is higher in SSCM.

3.3.2 Test of WMPP-based point source dispersion

The WMPP model code was extensively tested using meteorological observations from a 4-month measurement campaign at Nordbysletta in Lørenskog, Norway, in 2002 (Walker, 2011, 2010).

WMPP (see Sect. 2.2.2) is used in the plume rise module of SEGPLU (Walker and Grønskei, 1992) for the calculation of the wind speed at (1) stack height, (2) plume heights along the plume trajectory and (3) at final plume height. The modification of the plume rise module is similar to the “NILU plume” parameterization implemented in the WRF–EMEP (Weather Research and Forecasting–European Monitoring and Evaluation) model, as presented in Karl et al. (2014). In comparison with two simple schemes for plume rise calculation, NILU plume gave a lower final plume rise from an elevated point source for all tested atmospheric stability conditions. In neutral conditions, the maximum concentration at the ground (Cmax) was found to be roughly twice as high as for the two simple plume rise schemes. In unstable conditions, all plume rise schemes gave similar effective emission heights.

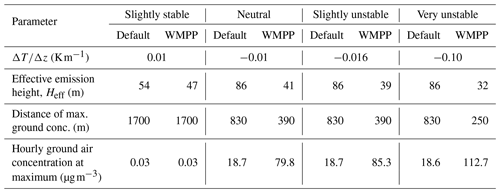

Table 4Test of the point source dispersion of SO2 (handled as an inert tracer) for different atmospheric stability conditions in flat terrain at a wind speed of 1 m s−1. Hourly concentration is given at the location where the maximum is found for the 5 d average within a radius of 2.0 km around the point source. Parameterization of point source: exhaust gas temperature: 20 ∘C; stack height: 10 m; exit velocity: 5 m s−1; stack radius: 0.5 m (circular opening). Emission rate: 1 g s−1. The default is the standard parameterization in EPISODE.

The WMPP integration in the sub-grid point source model for near-field dispersion around a point source was tested in different atmospheric stability conditions and compared to the standard point source parameterization in EPISODE (termed “default” in the following). A single point source was located at the midpoint of the 1 × 1 km2 grid cell. The dispersion of SO2, treated as a non-reactive tracer, released from the point source stack was studied by sampling ground air concentrations from a regular receptor grid with 100 m resolution within a radius of 2 km around the point source. Transport on the Eulerian grid was deactivated so that the test corresponds to a stand-alone test of the Gaussian point source model. Details about the point source and resulting hourly ground concentrations (averaged for 5 d) at the location of maximum impact, Cmax, for different stability conditions (slightly stable, neutral, slightly unstable, very unstable) are summarized in Table 4.

For WMPP, the maximum impact lies within 250 and 400 m downwind of the point source in neutral and unstable conditions. The effective emission height, Heff, in neutral conditions is about half of that computed by the default parameterization. For WMPP, Heff decreases with enhanced instability (from neutral to very unstable), while Cmax increases correspondingly. The increase in Cmax computed by WMPP is 41 %. Cmax should be roughly inversely proportional to the square of the effective emission height (Hanna et al., 1982); thus, the decrease from 41 m (neutral) to 32 m (very unstable) implies a potential increase in Cmax by 25 %. The higher increase in Cmax than expected might be due to continuous wind from one direction (225∘) and the relatively low wind speed (1 m s−1) in the test. For the default, Heff and Cmax are not affected by changing stability in neutral or unstable conditions; computed Cmax is a factor of 4–6 smaller than for WMPP. In stable conditions, Cmax is several orders of magnitude smaller than in neutral and unstable conditions for both plume rise parameterizations. The maximum impact is found at 1700 m of distance from the point source, which is comparable to previous tests with the point source model (Karl et al., 2014).

4.1 Setup of model experiments for the application for AQ modelling in Hamburg

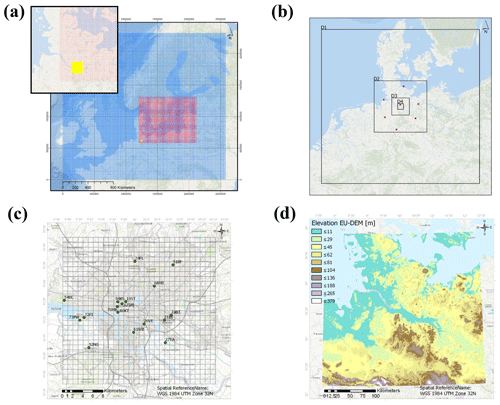

EPISODE–CityChem was run as part of a one-way nested chemistry-transport model chain from the global scale to the urban scale. The APTA (Asthma and Allergies in Changing Climate) global reanalysis (Sofiev et al., 2018) of the Finnish Meteorological Institute (FMI) provided the chemical boundary conditions for the European domain. The CMAQ v5.0.1 CTM (Byun et al., 1999; Byun and Schere, 2006; Appel et al., 2013) was run with a temporal resolution of 1 h over the European domain and an intermediate nested domain over northern Europe with 64 and 16 km horizontal resolution, respectively. CMAQ simulations were driven by the meteorological fields of the COSMO-CLM (COnsortium for SMall-scale MOdeling in CLimate Mode) model version 5.0 (Rockel et al., 2008) for the year 2012 using the ERA-Interim reanalysis of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) as forcing data (Geyer, 2014). Within the northern Europe domain, an inner domain over the Baltic Sea region with 4 km horizontal resolution was nested (Fig. 6a). The 4 km resolved CMAQ simulation of the Baltic Sea region provided the initial and hourly boundary conditions for the chemical concentrations in the Hamburg model domain.

Figure 6Model domains. (a) Nested CTM simulations with CMAQ showing the 16 km (CD16, blue grid) and 4 km (CD04, red grid) resolution nests as well as the study domain (yellow box); inset in the upper left corner shows a zoomed-in view of the study region. (b) Domains used for the nested meteorological simulations within TAPM (D1–D4; black frames); the red dots indicate DWD station locations, from which observation data were assimilated to nudge the wind field predictions in TAPM. (c) Study domain of Hamburg (30 × 30 km2) for simulation with CityChem, which corresponds to the innermost nest (D4) of the nested model chain of both CMAQ and TAPM simulations. Green dots indicate the positions of stations in the air quality monitoring network. (d) Terrain elevation (m a.s.l.) from the Digital Elevation Model over Europe (EU-DEM; https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/eu-dem, last access: 29 July 2019) for the extent of D2.

The hourly meteorological fields for the study domain of Hamburg (30 × 30 km2) were obtained from the inner domain in a nested simulation with TAPM (Hurley et al., 2005) with a 1 km horizontal resolution (D4 in Fig. 6b). The meteorological component of TAPM is an incompressible, non-hydrostatic, primitive equation model with a terrain-following vertical sigma coordinate for 3-D simulations; it was used for downscaling the synoptic-scale meteorology. The outer domain (D1 in Fig. 6b) was driven by the 3-hourly synoptic-scale ERA5 reanalysis ensemble means on a longitude–latitude grid at 0.3∘ grid spacing. In addition, wind speed and direction observations at seven measurement stations of the German Weather Service (DWD) are used to nudge the predicted solution towards the observations.

TAPM uses a vegetative canopy, soil scheme and an urban scheme with seven urban land use classes (Hurley, 2008) at the surface, while radiative fluxes, both at the surface and at upper levels, are also included. In regions belonging to one of the urban land use classes, specific urban land use characteristics, such as fraction of urban cover, albedo of urban surfaces, thermal conductivity of urban surface materials (e.g. concrete, asphalt, roofs), urban anthropogenic heat flux and urban roughness length, are used to calculate the surface temperature and specific humidity as well as surface fluxes and turbulence. A complete list of the meteorological variables and fields used from TAPM as input to EPISODE–CityChem for the AQ simulations is given in the user's guide for EPISODE–CityChem, which is included in the CityChem distribution.

For a better representation of local features, the coarsely resolved standard land cover classes and elevation heights, which are provided together with TAPM, were updated with 100 m CORINE Land Cover 2012 data (CLC, 2012), and terrain elevation data were adopted from the German Digital Elevation Model (BKG, 2013) at 200 m horizontal resolution.

The procedure to adapt hourly 3-D concentrations of the CMAQ model computed for the 4 km resolution domain as lateral and vertical boundary conditions is described in Sect. 2.3.1 and Appendix D. CMAQ concentrations from the 4 km resolution domain were interpolated to the 1 km resolution (in UTM projection) of the Hamburg study domain, preserving a nesting factor of four (64, 16, 4, 1 km) for the nested model chain. The study domain is located in the southwest part of the 4 km CMAQ domain (CD04); the west border of the study domain is 30 km from the CD04 west border, and the south border is 21 km from the CD04 south border (inset in Fig. 6a). The contribution of the recirculation of NOx from the coarser outer domain to the budget of NOx in the inner domain is very small due to the predominant westerly winds.

4.1.1 Description of the model setup and configuration for Hamburg

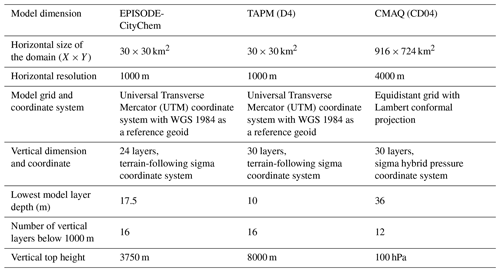

The EPISODE–CityChem simulation was performed using the recommended numerical schemes for physics and chemistry, including the new urban parametrization for vertical eddy diffusivity (urban K(z), see part one; Hamer et al., 2019). The segmented plume model SEGPLU with WMPP-based plume rise was used for the point source emissions. The line source model HIWAY-2 with the street canyon option was used for the line source emissions. Table 1 summarizes the chosen model processes and options. The vertical and horizontal structure of the 3-D Eulerian grid in EPISODE–CityChem is determined by the model domain structure of the TAPM simulation. The model input of boundary conditions and gridded area emissions have to be with the same horizontal resolution as the meteorological fields. A horizontal resolution of 1000 m was chosen for the 30 × 30 km2 domain of Hamburg. The horizontal resolution is in practice limited by the available gridded area source emission data. Finer resolution increases the required computational time; for instance, using a horizontal resolution of 500 m for the study domain results in a number of grid cells that is 4 times higher and a halved model time step (dt=300 s instead of dt=600 s), increasing the total computational time for one simulation month by a factor of 2.8 compared to the applied resolution. The EPISODE–CityChem model was set up with the vertical dimension and resolution matching that of TAPM, with a layer top at 3750 m of height above the ground, avoiding the need for vertical interpolation. The layer top heights of the lowest 10 layers were 17.5, 37.5, 62.5, 87.5, 125, 175, 225, 275, 325 and 375 m. Table 5 provides details on the vertical and horizontal structure of EPISODE–CityChem and TAPM (pollution grid) D4 as used for the Hamburg study domain and CMAQ (CD04). The computational time for a 1-month simulation with EPISODE–CityChem is 10.7 h on an Intel® Xeon (R) CPU E5-2637 v3 at 3.50 GHz with 64 GB of RAM.

Table 5Vertical and horizontal structure of the 3-D Eulerian grid of the EPISODE–CityChem model and comparison with TAPM (D4) and CMAQ (CD04) for the simulation of AQ in Hamburg.

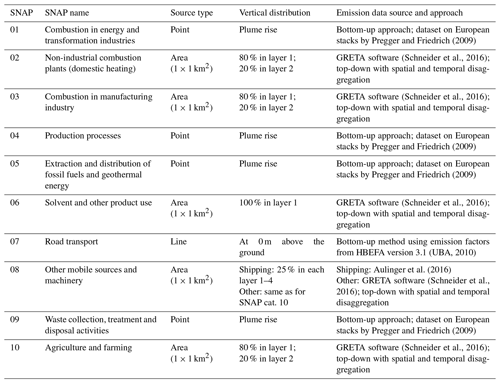

Table 6Emission sector data for the simulation of air quality in Hamburg. Classification according to Selected Nomenclature for sources of Air Pollution (SNAP). The top heights of layers 1, 2, 3 and 4 are 17.5, 37.5, 62.5 and 87.5 m above the ground, respectively. Point source emission data for SNAP categories 01, 04, 05 and 09 were collected from the PRTR database (PRTR, 2017) and from the registry of emission data for point sources in Hamburg as reported under the German Federal Emission Control Act (BImSchV 11).

Area, point and line source emissions for the study domain of Hamburg were used from various data sources for the different emission sectors classified by the Selected Nomenclature for sources of Air Pollution (SNAP) of the European Environmental Agency (EEA), applying top-down and bottom-up approaches (Matthias et al., 2018). Table 6 gives an overview. Spatially gridded annual emission totals for area sources with a grid resolution of 1 × 1 km2 were provided by the German Federal Environmental Agency (Umweltbundesamt, UBA). The spatial distribution of the reported annual emission totals was calculated at UBA using the ArcGIS-based software GRETA (Gridding Emission Tool for ArcGIS) (Schneider et al., 2016). Hourly area emissions with a 1 km horizontal resolution for SNAP cat. 03 (commercial combustion), 06 (solvent and other product use), 08 (other mobile sources, not including shipping) and 10 (agriculture and farming) were derived from the UBA area emissions by temporal disaggregation using monthly, weekly and hourly profiles.

For SNAP cat. 02 (domestic heating) the daily average ground air temperature obtained from the TAPM simulation is used to create the annual temporal profiles. The day-to-day variation of domestic heating emissions is based on the heating degree-day concept implemented in the Urban Emission Conversion Tool (UECT) (Hamer et al., 2019). Domestic heating emissions (SNAP cat. 02) for Hamburg are distributed between 32 % district heating, 40 % natural gas, 14 % fuel oil and 14 % electricity (Schneider et al., 2016).

NMVOC emissions in the UBA dataset were distributed over individual VOCs of the chemical mechanism using the VOC split of the EMEP model (Simpson et al., 2012) for all SNAP sectors.

A total of 120 point sources were extracted from the PRTR (Pollutant Release and Transfer Register) database (PRTR, 2017) and from the registry of emission data for point sources in Hamburg, representing the largest individual stack emissions.

The line source emission dataset (emissions of NOx, NO2 and PM10) provided by the city of Hamburg contained 15 816 road links within the study domain. The NOx emission factor from road traffic for the year 2012 was increased by 20 % for all street types because the average NOx emission factor in the new HBEFA (Handbook Emission Factors for Road Traffic) v3.3 for passenger cars is higher by 19.4 % (diesel cars: 21 %) than in HBEFA v3.1 used in the road emission inventory (UBA, 2010). To estimate NMVOC traffic emissions, an average NMVOC∕NOx ratio of 0.588, derived from UBA data for SNAP cat. 07, was used.

An NO2∕NOx ratio of 0.3 was applied to recalculate NO2 emissions for this study because of the expected higher real-world NO2 emissions from diesel vehicles. The applied value is higher than suggested by the reported range (3.2–23.5 vol %) of the primary NO2 emission fraction from vehicular traffic in London (Carslaw and Beevers, 2005) and the NO2∕NOx ratio of 0.22 for passenger cars in urban areas assumed by Keuken et al. (2012) for the Netherlands. The use of the high NO2∕NOx ratio for the Hamburg vehicle fleet is consistent with the higher NO2∕NOx ratio from diesel passenger cars (from 0.12 to >0.5; Carslaw and Rhys-Tyler, 2012) and the review by Grice et al. (2009), who assumed that Euro 4–6 passenger cars emit 55 % of the total NOx as NO2.

4.2 Presentation and evaluation of model results

4.2.1 Setup of the model evaluation and performance analysis

A 1-year simulation with EPISODE–CityChem was performed for the study domain using the model setup as described in Sect. 4.1.1. Model results were compared to results from the standard EPISODE model to assess the total effect of the new implementations of the CityChem extension. In the standard EPISODE model, the PSS approximation is used at the receptor points and on the Eulerian grid; the street canyon model and the WMPP module were deactivated. For the simulation with EPISODE–CityChem and standard EPISODE, the boundary conditions from hourly 3-D concentrations of CMAQ were taken as described in Sect. 2.3.1. In addition, EPISODE–CityChem results were compared to results from the air pollution module of TAPM, which is used as a reference model in this study. The TAPM run was performed with the same horizontal resolution (1 km), as well as identical meteorological fields and urban emissions, but with 2-D boundary conditions instead of 3-D boundary conditions. The hourly 2-D boundary concentrations for TAPM were prepared by using the horizontal wind components on each of the four lateral boundaries to weight the CMAQ concentrations surrounding the Hamburg study domain. Concentrations for the TAPM boundary conditions were taken from the seventh vertical model layer of the CMAQ simulation, with a mid-layer height of approximately 385 m above the ground, where average concentrations are not significantly affected by urban emissions.

Evaluation of the model results for Hamburg was done in a four-stage procedure:

-

statistical performance analysis of the prognostic meteorological model component of TAPM (Sect. 4.2.2);

-

evaluation of the temporal variation of modelled concentrations against observed concentrations (Sect. 4.2.3);

-

evaluation of the spatial variation of the annual mean concentrations (Sect. 4.2.4); and

-

model performance analysis with respect to the objectives set forth in the AQD for the use of the model in policy applications (Sect. 4.2.5).

Statistical indicators of the evaluation included the mean (modelled ∕ observed), standard deviation (SD; modelled ∕ observed), correlation coefficient (Corr), root mean square error (RMSE), overall bias (Bias), normalized mean bias (NMB) and index of agreement (IOA). See Appendix E for the definition of the statistical indicators.

The FAIRMODE (Forum for Air Quality Modelling in Europe) DELTA tool version 5.6 (Thunis et al., 2012a, b, 2013; Pernigotti et al., 2013; FAIRMODE, 2014; Monteiro et al., 2018) was used for the evaluation of model results from air quality simulations for Hamburg. The DELTA tool focuses primarily on the air pollutants regulated in the current AQD (EC, 2008).

4.2.2 Evaluation of downscaled meteorological data

Downscaled meteorological data on temperature, relative humidity, total solar radiation, wind speed and wind direction were examined. Hourly-based data from the meteorological station at the Hamburg airport (Fuhlsbüttel) (operated by DWD) and from the 280 m high Hamburg weather mast at Billwerder (operated by Universität Hamburg) were analysed. Observation data from the DWD station at 10 m of height and from the Hamburg weather mast at 10 and 50 m of height were used in the analysis. TAPM modelled meteorological data from the 1 × 1 km2 grid cell of the D4 domain, where the stations are located, at the corresponding height were extracted for comparison with observations. Table S4 provides an overview of the statistical analysis of TAPM data.

Hourly temperature predicted by TAPM was in excellent agreement with the observed temperature at both stations and both heights, showing high correlation (Corr ≥ 0.98) and small overall bias (≤ 1.00 ∘C). Relative humidity also showed good agreement but with lower correlation (Corr = 0.74). Total solar radiation was predicted by TAPM with high correlation (Corr = 0.86) but a high positive overall bias of 27 W m−2. Situations with reduced solar radiation due to high cloud coverage are often not well captured by TAPM. The IOA for temperature, relative humidity and total solar radiation was 0.99 (average of all observations), 0.86 and 0.92, respectively.

TAPM shows good predictive capabilities for wind speed and direction. Due to the assimilation of wind observations at the DWD Hamburg airport station for nudging wind speed and direction in TAPM meteorological runs, the meteorological performance for wind speed and direction was only compared at the Hamburg weather mast. Modelled hourly data for wind speed at the Hamburg weather mast agreed well with the observations throughout the year at 10 m (Corr = 0.87, Bias = −0.08 m s−1) and 50 m of height (Corr = 0.85, Bias = −0.02 m s−1); they were within the observed variability. Southwest and west are the most frequent wind directions in Hamburg due to prevailing Atlantic winds, followed by winds from the southeast (Bruemmer et al., 2012). Mean wind direction was computed as a circular average (unit vector mean wind direction) for model and observation data. At the Hamburg weather mast, modelled versus observed wind directions show good agreement at 10 and 50 m of height (IOA ≥ 0.89) with a bias in the mean wind direction of 16.9 and 6.2∘ at 10 and 50 m, respectively. The difference is due to a slightly higher frequency of winds from the west predicted by TAPM.

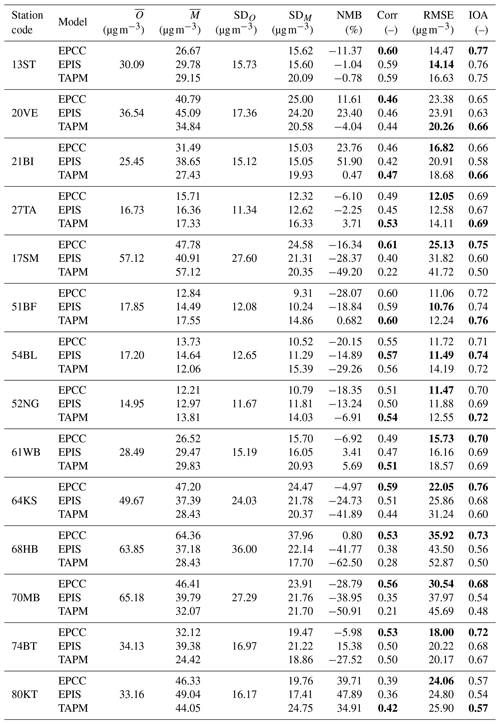

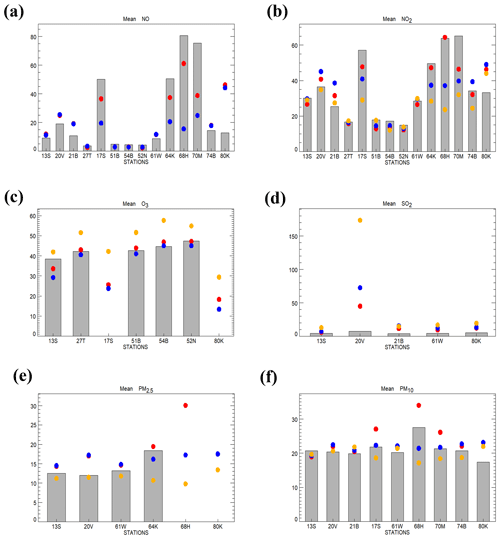

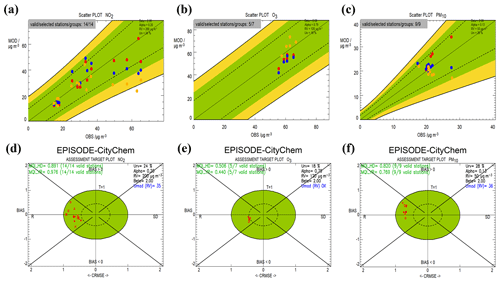

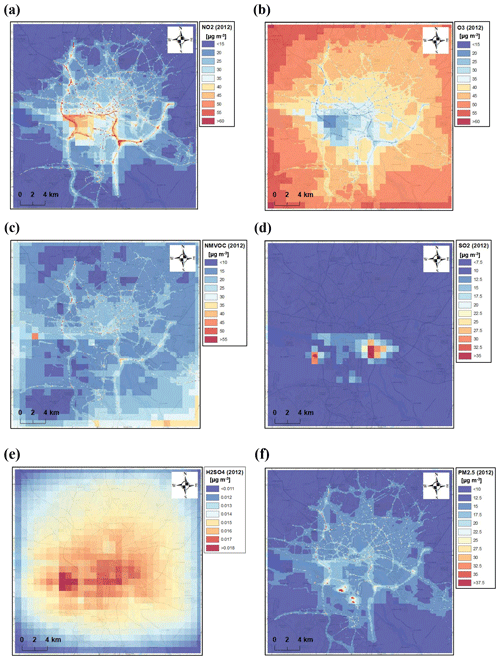

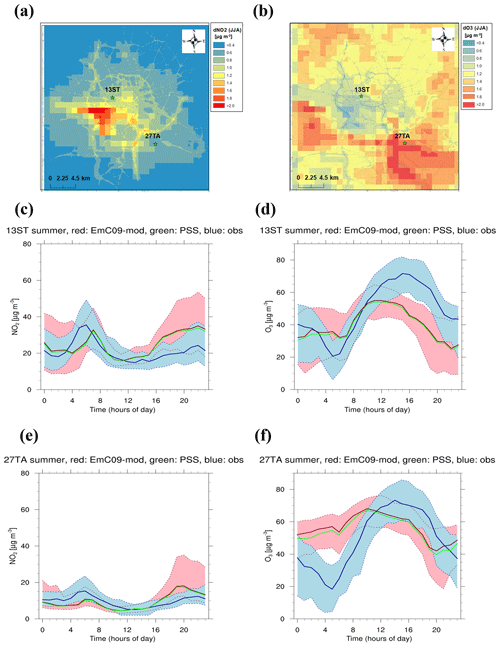

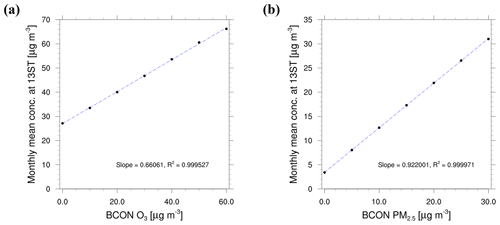

4.2.3 Evaluation of the temporal variation of pollutants