the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Threshold atmospheric electric fields for initiating relativistic runaway electron avalanches: theoretical estimates and CORSIKA simulations

Liza Hovhannisyan

Mary Zazyan

We examine the threshold atmospheric electric field (Eth) required to initiate a runawayavalanche in Earth's atmosphere. We compare the traditional, thirty-year-old theoretical threshold with its recently updated value and with the threshold derived from CORSIKA-simulated avalanches (Ez). The altitude dependence of these thresholds is analyzed, considering how changes in air density affect avalanche development. This study is vital for understanding high-energy atmospheric phenomena in both the lower and upper atmosphere, including thunderstorm ground enhancements (TGEs) and gamma glows, and for refining atmospheric electric field (AEF) models based on particle flux measurements.

- Article

(950 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

-

Introduces a refined framework for determining the threshold atmospheric electric fields (Eth) required to initiate relativistic runaway electron avalanches (RREAs) and thunderstorm ground enhancements (TGEs).

-

Compares classical (Eth≈ 2.80 kV cm−1 × n) and updated (Eth≈ 2.67 kV cm) theoretical thresholds with altitude-dependent thresholds derived from CORSIKA simulations.

-

Demonstrates that realistic avalanche development requires fields of 15 %–22 % stronger than theoretical values, depending on altitude and air density.

-

Provides a reproducible simulation methodology for integrating experimental particle-flux measurements into atmospheric electricity models across multiple research stations.

Free electrons are abundant in the troposphere. The altitude at which their flux reaches its highest point, called the Regener–Pfotzer maximum (Regener, 1933). It depends on the geomagnetic cutoff rigidity (Rc), the type of particles being measured, and the phase and strength of the solar cycle. Recent observations, supported by PARMA4.0 calculations (Sato, 2016), show that at middle to low latitudes (Rc = 3–8 GV), the highest flux of charged particles occurs at altitudes around 12–14 km (see Fig. 3 in Ambrozová et al., 2023).

Atmospheric electric fields (AEFs) generated by thunderstorms transfer energy to free electrons, accelerate them, and, under certain conditions, induce electron-photon avalanches. Gurevich et al. (1992) identified the conditions necessary for extensive multiplication of electrons from an energetic seed electron injected into a strong AEF region. This process is known as the Relativistic Runaway Electron Avalanche (RREA; Babich et al., 2001; Alexeenko et al., 2002). A numerical approach for solving the relativistic Boltzmann equation for runaway electron beams (Symbalisty et al., 1998) aids in estimating the threshold AEF (Babich et al., 2001; Dwyer, 2003) required to trigger RREA. As demonstrated by GEANT4 and CORSIKA simulations (Chilingarian et al., 2012, 2022, 2024), the RREA process is a threshold phenomenon, with avalanches initiating when the atmospheric AEF exceeds a certain threshold that depends on air density. The AEF must also be sufficiently extended to support the growth of avalanches. At standard temperature and pressure in dry air at sea level, Eth≈ 2.80 kV cm, where air density n is relative to the International Standard Atmosphere (ISA) sea-level value (see the recent update of the threshold energy Eth≈ 2.67 kV cm in Dwyer and Rassoul, 2024). This threshold field is slightly higher than the breakeven field, which corresponds to theelectron energy at which minimum ionization occurs. If electrons traveled exactly along AEF lines, it would define the threshold for runaway electron propagation and the start of avalanche formation. However, the paths of electrons deviate due to Coulomb scattering with atomic nuclei and Møller scattering with atomic electrons, causing deviations from the near-vertical AEF. Additionally, secondary electrons produced by Møller scattering are not generated along the field line; therefore, AEFs must exceed the theoretical RREA threshold Eth by approximately 10 %–20 % for electrons to run away and trigger an avalanche.

To understand how avalanches develop in an electrified atmosphere and to compare the new and updated Eth with the particle-intensity abrupt growth, we used the CORSIKA code (Heck et al., 1998), version 7.7500, which accounts for the effect of AEFs on particle transport (Buitink et al., 2009). The growth of RREA increases the cloud's electrical conductivity. Numerous studies (Marshall et al., 1995; Stolzenburg et al., 2007) have indicated that lightning flashes tend to occur when the applied electric field exceeds the RREA threshold by roughly 20 %–30 %. RREA simulation codes do not include a lightning initiation mechanism. Therefore, one can artificially raise the AEF strength beyond a realistic value to produce billions of avalanche particles; however, this approach lacks physical justification. As a result, we do not test AEFs stronger than 2.5 kV cm−1 at altitudes of 3–6 km. The RREA simulation was performed for vertical seed electrons with a uniform AEF that exceeded the Eth by a few tens of percent. An introduced fixed uniform AEF shifts the surplus to Eth at different heights by different percentages, corresponding to air density. The chosen seed electron energy spectrum was based on the EXPACS Excel-based program (Sato, 2016), following a power-law with an index of 1.173 for energies from 1 to 300 MeV. During TGE events on Aragats, the typical distance to the cloud base is estimated to be 25–200 m (see Fig. 17 in Chilingarian et al., 2020); therefore, in our simulations, particle propagation continued in dense air for an additional 25, 50, 100, and 200 m before detection.

The simulations included 1000 to 10 000 events for AEF strengths from 1.55 to 2.5 kV cm−1. Electron and gamma-ray propagation were tracked until their energies dropped to 0.05 MeV. Each simulation event corresponds to the propagation of a single seed electron; multiple events were used to obtain statistically stable averages to reliably estimate the resulting threshold electric fields. The CORSIKA code models the development of RREA by calculating the number of electrons and gamma rays at different stages of the cascade development at 200-meter intervals. At all stations, the atmospheric electric field was implemented as a vertically uniform layer with a thickness of 2000 m above the observation levels. Besides the Aragats and Nor Amberd research stations on the slopes of Mt. Aragats in Armenia, we also conducted simulations for the Slovakian and Chinese research stations at Lomnický Štít (Chum et al., 2020) and the Tibetan plateau. LHAASO (Large High Altitude Air Shower Observatory, Aharonian et al., 2023) is situated at 4410 m a.s.l. It provides an ideal platform for studying atmospheric particle acceleration, owing to its thin atmosphere and the high likelihood of runaway electron avalanche formation. For LHAASO, we present CORSIKA simulation results showing increases in electron and photon fluxes under AEF strengths ranging from 1.55 to 1.9 kV cm−1. The number of electrons and photons was recorded at altitudes ranging from 6510 to 4510 m. Lomnický Štít is located at an altitude of 2630 m in Slovakia. CORSIKA simulations were performed for various vertical AEFs ranging from 1.9 to 2.3 kV cm−1. The number of electrons and photons was recorded at altitudes ranging from 4734 to 2734 m. Significant increases in flux were observed with stronger-than-threshold fields, confirming the development of robust RREA. Saturation trends in the growth of electrons and photons suggest that the threshold field, Eth, at Lomnický Štít is approximately 2.3 kV cm−1. These results support earlier findings from Aragats and Nor Amberd and emphasize the altitude dependence of Eth. Due to the thinner air at LHAASO, the TGEs occurred at a much lower value of 1.7 kV cm−1. In Fig. 1a–d, we display the development of RREA at different atmospheric depths and for various physically justified strengths of the AEF. The curves are scaled for a single seed electron for easier comparison with experimentally measured intensities.

For large values of AEFs, the number of avalanche particles rose exponentially. For lower values of AEF, we observe saturation of the particle flux when AEF becomes lower than the threshold electric field (dependent on air density); the RREA process attenuates before reaching the observation level (see the yellow and blue curves in Fig. 1a–d).

Figure 1Longitudinal development of relativistic runaway electron avalanches (RREA) at four high-altitude observation sites: (a) Aragats, (b) Lomnický Štít, (c) Nor Amberd, and (d) LHAASO. The number of electrons is normalized to a single seed electron and shown as a function of depth within the electric field region. For each site, simulations were performed for several electric field strengths, as indicated in the legends. Avalanche development is sampled every 200 m across the field region. After exiting the electric field, electron propagation is followed for an additional 100 m in free space before reaching the detector.

Figure 1 illustrates the dependence of electron multiplication on electric field strength and highlights the altitude-dependent conditions required for sustained avalanche development.

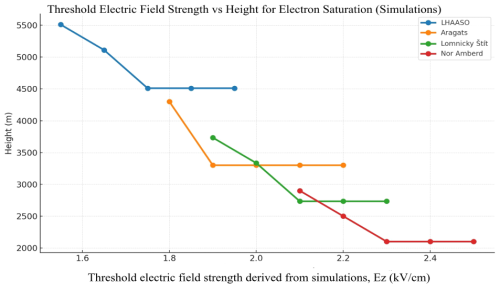

We estimate the “simulated” thresholds, Ez values, at the heights where the number of avalanche particles stops rising, as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2Simulated threshold electric field strength, Ez, versus altitude for several high-altitude stations. The threshold is defined as the electric field strength at which the growth of avalanche electrons saturates.

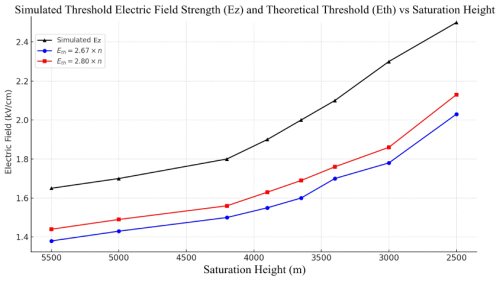

Figure 3Simulated threshold electric field strength, Ez, and theoretical threshold electric fields, Eth, as a function of saturation (rise stopping) altitude.

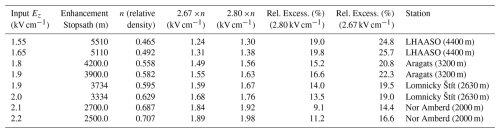

Table 1Excess of Ez over Eth. Stopping altitudes and theoretical threshold field comparisons for heights 2500–5550 m.

In Fig. 3 and Table 1, we compare the “simulated” threshold Ez with the theoretical ones. Simulations derive higher values than theoretical estimates, especially for high Eth values (low altitudes) at all four research stations. Theoretical threshold fields are computed as 2.67 and 2.80 kV cm. The percentage of enhancement indicates how much the applied field exceeds the theoretical thresholds. Strong AEFs, where the cascade did not attenuate, were not included in the table.

Both the classical threshold field (Eth≈ 2.80 kV cm) and its updated version (Eth≈ 2.67 kV cm) are derived under idealized assumptions; the difference between them results from refinements in modeling particle energy los sprocesses. The earlier estimate of 2.80 kV cm was based on basic energy balance considerations using older ionization loss models and assumed monoenergetic electrons. This threshold is slightly above the breakeven field, where energy gain equals average energy loss. The updated 2.67 kV cm value, introduced by Dwyer and Rassoul (2024), incorporates more accurate relativistic Boltzmann solutions, improved ionization and bremsstrahlung cross-sections, and a probabilistic treatment of runaway thresholds across realistic energy spectra. While both thresholds assume idealized, field-aligned electron motion in a uniform medium, the updated value is physically more consistent. It predicts a slightly lower field strength needed for initial runaway. However, CORSIKA simulations show that this refined threshold is insufficient for sustained avalanche growth under real atmospheric conditions due to scattering and finite path effects. Moreover, it deviates more from the simulated value than the “classical”, 30-year-old estimate. Multiple physical processes inhibit ideal runaway propagation. Coulomb scattering with atmospheric nuclei and Møller scattering with electrons cause substantial angular deflection and energy redistribution. Secondary electrons are not generated strictly along the field direction, and many lose energy before gaining sufficient momentum to continue avalanche growth. As a result, electrons must be accelerated in fields stronger than the threshold to overcome these losses and maintain avalanche conditions. CORSIKA simulations, which incorporate all major interaction mechanisms – includingCoulomb and Møller scattering, bremsstrahlung losses, finite propagation distances, andrealistic secondary cosmic ray spectra – show that avalanches fully developonly when the applied field exceeds the theoretical threshold by a measurable margin. For the updated 2.67 kV cm value, we observe a required excess of approximately 20 %–22 % at the Aragats station (∼ 3200–4200 m a.s.l.), whereas for the classical 2.80 kV cm threshold, the excess is typically 15 %–17 %. Interestingly, this required excess decreases with increasing air density, as observed inthe Nor Amberd simulations. At lower altitudes (∼ 2500–2700 m a.s.l.), the differencebetween the applied and threshold fields is reduced: only 14 %–16 % above 2.67 kV cm, and about 9 %–11 % above 2.80 kV cm.

This trend can be explained as follows: In denser air, the chances of energy-loss interactions increase, but so does the likelihood of electron multiplication through ionization and bremsstrahlung over shorter distances. The avalanche can develop more quickly because seed electrons encounter more target atoms in a given path length. As a result, the necessary “headroom” above the threshold field for sustained multiplication is smaller. Simply put, the efficiency of avalanche formation improves in denser air, even though the absolute threshold field is higher. This results in a smaller relative excess being required above the theoretical threshold. Therefore, although the threshold field scales linearly with air density, the required enhancement factor does not. It decreases with increasing density due to a balance between energy loss and multiplication processes, all of which are faithfully captured in the CORSIKA simulation framework. This emphasizes the importance of altitude-dependent analysis in interpreting Thunderstorm Ground Enhancements (TGEs) and suggests that scaling laws based solely on density may overlook subtler effects arising from atmospheric structure and shower development dynamics.Among these effects is the local temperature profile, which can modify air density and, consequently, slightly affect the effective threshold field. A more detailed treatment incorporating measured or modeled temperature profiles could further refine threshold estimates for individual events; however, such event-specific modeling is beyond the scope of the present work.

All materials under the authors' control that are required to reproduce the results presented in this manuscript are publicly available in a Zenodo repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17986152 (Hovhannisyan, 2025).

The Zenodo archive is organized as follows:

-

code/. This directory contains auxiliary materials and user-level post-processing codes (e.g., easread.f) required to ensure the reproducibility of the simulations. These codes were used to analyze the output data of the CORSIKA simulations and to derive the numerical results presented in the manuscript.

-

inputs/. This directory contains all CORSIKA input files used in the simulations for each observation site, including the complete input cards and definitions of the thunderstorm electric-field configurations (el.input, elfield.c), observation levels, energy cutoffs, and all relevant simulation parameters.

-

data/. This directory contains the CORSIKA simulation output files (DAT files) corresponding to the electric-field configurations and observation sites analyzed in the manuscript. The data are organized by station and electric-field strength.

-

tables/. This directory contains the final numerical tables used in the manuscript, including threshold electric-field values, stopping altitudes, relative air densities, and percentage excesses over theoretical thresholds.

-

figures/. This directory contains all figures included in the manuscript, generated directly from the simulation output and the processed numerical data.

In addition, the repository root contains the official technical documentation of the CORSIKA simulation framework (CORSIKA_GUIDE7.7550.pdf) and a README file describing the structure and contents of the archive.

The CORSIKA simulation framework is a licensed third-party Monte Carlo code developed and maintained by the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT). The exact CORSIKA version used in this work is specified in the manuscript and is available for scientific use directly from the official KIT distribution portal. All user-provided inputs, configurations, auxiliary codes, and simulation outputs required for reproducibility are provided in the Zenodo archive.

Together, these materials ensure full reproducibility of the simulations and results presented in this study for any user with legitimate access to the CORSIKA framework.

AC and MZ designed the simulation experiments with the CORSIKA code, and LH performed the simulations. AC prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This research has been supported by the Science Committee of the Republic of Armenia (grant No. 21AG-1C012).

This paper was edited by Cynthia Whaley and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Aharonian, F., An, Q., Axikegu, et al.: Flux variations of cosmic ray air showers detected by LHAASO-KM2A during a thunderstorm on 10 June 2021, Chin. Phys. C, 47, 015001, https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1137/ac9371, 2023.

Alexeenko, V. V., Khaerdinov, N. S., Lidvansky, A. S., and Petkov, V. B.: Transient variations of secondary cosmic rays due to atmospheric electric field and evidence for pre-lightning particle acceleration, Phys. Lett. A, 301, 299–306, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9601(02)00981-7, 2002.

Ambrozová, I., Kákona, M., Dvořák, R., Kákona, J., Lužová, M., Povišer, M., Sommer, M., Velychko, O., and Ploc, O.: Latitudinal effect on the position of the Regener–Pfotzer maximum investigated by balloon flight HEMERA 2019 in Sweden and balloon flights FIK in Czechia, Radiat. Prot. Dosim., 199, 2041, https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/ncac299, 2023.

Babich, L. P., Donskoy, E. N., Kutsyk, I. M., and Kudryavtsev, A. Y.: Comparison of relativistic runaway electron avalanche rates obtained from Monte Carlo simulations and kinetic equation solution, IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci., 29, 430–438, https://doi.org/10.1109/27.928940, 2001.

Buitink, S., Huege, T., Falcke, H., Heck, D., and Kuijpers, J.: Monte Carlo simulations of air showers in atmospheric electric fields, Astropart. Phys., 33, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.astropartphys.2009.10.006, 2009.

Chilingarian, A., Mailyan, B., and Vanyan, L.: Recovering the energy spectra of electrons and gamma rays coming from thunderclouds, Atmos. Res., 114–115, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2012.05.008, 2012.

Chilingarian, A., Hovsepyan, G., Karapetyan, T., Karapetyan, G., Kozliner, L., Mkrtchyan, H., Aslanyan, D., and Sargsyan, B., Structure of thunderstorm ground enhancements, PRD 101, 122004, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.101.122004, 2020.

Chilingarian, A., Hovsepyan, G., Karapetyan, T., Sargsyan, B., and Zazyan, M.: Development of relativistic runaway avalanches in the lower atmosphere above mountain altitudes, EPL, 139, 50001, https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/ac8763, 2022.

Chilingarian, A., Karapetyan, T., Aslanyan, D., and Sargsyan, B.: Dataset on extreme thunderstorm ground enhancements registered on Aragats in 2023, Data in Brief, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2024.110554, 2024.

Chum, J., Langer, J., Baše, M., Kollárik, I., Strhársky, G., and Diendorfer, J. R.: Significant enhancements of secondary cosmic rays and electric field at high mountain peak during thunderstorms, Earth Planets Space, 72, 28, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-020-01155-9, 2020.

Dwyer, J. R.: A fundamental limit on electric fields in air, Geophys. Res. Lett., 30, 2055, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL017781, 2003.

Dwyer, J. R. and Rassoul, H. K.: High-energy radiation from thunderstorms and lightning with LOFT, arXiv [preprint], https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1501.02775, 2024.

Gurevich, G., Milikh, R., and Roussel-Dupré, R.: Runaway electron mechanism of air breakdown and preconditioning during a thunderstorm, Phys. Lett. A, 165, 463–468, https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9601(92)90348-P, 1992.

Heck, D., Knapp, J., Capdevielle, J. N., Schatz, G., and Thouw, T.: CORSIKA: A Monte Carlo code to simulate extensive air showers, Report FZKA-6019, Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe, https://doi.org/10.5445/IR/270043064, 1998.

Hovhannisyan, L.: Code and Data for: Threshold Atmospheric Electric Fields for Initiating Relativistic Runaway Electron Avalanches, Zenodo [code, data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17986152, 2025.

Marshall, T. C., McCarthy, M. P., and Rust, W. D.: Electric field magnitudes and lightning initiation in thunderstorms, J. Geophys. Res., 100, 7097–7103, https://doi.org/10.1029/95JD00020, 1995.

Regener, E.: The intensity of penetrating ultra-radiation in the atmosphere, Z. Phys., 80, 174–183, 1933.

Sato, T.: Analytical model for estimating the zenith angle dependence of terrestrial cosmic-ray fluxes, PLoS ONE, 11, e0160390, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160390, 2016.

Stolzenburg, M., Marshall, T. C., Rust, W. D., Bruning, E., MacGorman, D. R., and Hamlin, T.: Electric field values observed near lightning flash initiations, Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L04804, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL028777, 2007.

Symbalisty, E. M. D., Roussel-Dupré, R. A., and Yukhimuk, V. A.: Finite volume solution of the relativistic Boltzmann equation for electron avalanche studies, IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci., 26, 1575–1582, https://doi.org/10.1109/27.736065, 1998.