the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Retrieving atmospheric thermodynamic and hydrometeor profiles using a thermodynamic-constrained Kalman filter 1D-Var framework based on ground-based microwave radiometer

Qi Zhang

Yu Wu

Bin Deng

Junjie Yan

Ground-based microwave radiometers (GMWRs) provide continuous thermodynamic profiling but suffer from degraded accuracy under cloudy and precipitating conditions when using classical one-dimensional variational (1D-Var) retrievals. To address this, we develop a thermodynamic-constrained Kalman filter variational framework (TCKF1D-Var) that enforces moist-thermodynamic consistency through the use of virtual potential temperature as the control variable, employs a ratio-based cost function independent of prescribed background and observation error covariances, and integrates a diagnostic microphysics closure to represent liquid and ice water. Validation over 44 GMWR sites in North China, including seven with collocated radiosondes, shows that TCKF1D-Var systematically reduces temperature and humidity biases relative to ERA5 (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis version 5) and 1D-Var, with the largest improvements above 2 km for temperature and below 5.5 km for humidity. Temperature root-mean-square errors remain comparable to ERA5 and lower than 1D-Var below 8.5 km, while humidity errors are improved near the surface though degraded in the mid-troposphere due to vertical-resolution mismatch and channel cross-talk. Evaluation against collocated EarthCARE (Earth Clouds, Aerosols and Radiation Explorer) cloud liquid water content profiles demonstrates that TCKF1D-Var yields the lowest biases and errors and best reproduces observed distributions, confirming the benefit of the microphysics constraint. Case analyses of short-duration heavy rainfall further show that TCKF1D-Var enhances precursor signals of convection, extending the effective lead time for early warning relative to ERA5 and substantially outperforming 1D-Var. These results highlight the value of embedding physical constraints and microphysical closure within GMWR retrievals, offering a practical pathway to improve continuous thermodynamic monitoring and support high-impact weather nowcasting.

- Article

(8710 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

High-resolution thermodynamic and hydrometeor profiles are essential for both atmospheric research and operational weather forecasting (Wulfmeyer et al., 2015; Wagner et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2019). Rapid vertical changes in temperature and water vapor associated with synoptic features can initiate high-impact weather events, including squall lines (Löhnert and Maier, 2012; Geerts et al., 2017) and mesoscale convective systems (Teixeira et al., 2025). Moreover, long-term, high-resolution datasets of temperature and humidity profiles in the PBL can help reveal how anthropogenic influences, such as urbanization, alter the thermodynamic structure (Barrera-Verdejo et al., 2016; Turner and Löhnert, 2021). Recognizing this need, the China Meteorological Administration (CMA) launched the “Weak-Link Remediation Project” in 2021, deploying ground-based microwave radiometers (GMWRs) and other instrumemts at selected sites to continuously retrieve high-resolution thermodynamic and hydrometeor profiles throughout the troposphere fill the observational gap between sparse radiosonde launches and satellite overpasses. This makes the GMWRs particularly valuable for monitoring fast-changing atmospheric signals and supporting short-range weather prediction.

However, the performance of GMWR retrievals strongly depends on atmospheric conditions. Under clear-sky conditions, GMWR observations generally provide reliable temperature and humidity profiles with reasonable accuracy compared to radiosondes, regardless of methodological differences (Weisz et al., 2013; Ebell et al., 2017; Adler et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Xu, 2024). In contrast, under non-clear-sky conditions, significant retrieval biases can arise. Clouds introduce additional scattering and emission, particularly liquid water clouds that affect the 22–31 GHz water vapor absorption band, leading to overestimation of humidity and distortion of the retrieved vertical distribution (Zhang et al., 2024; Viggiano et al., 2025). Likewise, precipitation causes strong attenuation and scattering in both water vapor and oxygen absorption channels, degrading the information content for temperature retrievals (Kummerow et al., 2022; Christofilakis et al., 2020). These effects reduce retrieval reliability, especially in the lower troposphere where cloud and precipitation impacts are strongest.

Consequently, although GMWRs remain indispensable for continuous thermodynamic profiling, their application under cloudy and precipitating conditions requires advanced retrieval frameworks to mitigate these limitations. In this study, we introduce a novel Kalman filter–based one-dimensional variational optimal estimation framework (TCKF1D-Var) that integrates a thermodynamic conservation–constrained cost function with a cloud microphysics parameterization scheme, which generates retrievals of temperature, humidity, and hydrometeor profiles from microwave radiometer observations with higher accuracy. A comprehensive comparison with classical one-dimensional variational (1D-Var) method demonstrates that the proposed approach substantially improves retrieval accuracy, highlighting both its methodological novelty and its effectiveness in producing high-quality atmospheric profile products.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the study sites, instruments, and datasets employed. Section 3 presents the technical framework and implementation of the 1D-Var and TCKF1D-Var optimal estimation methods. Section 4 evaluates the accuracy of thermodynamic profiles retrieved by these three frameworks under both daytime and nighttime conditions, as well as under different weather scenarios. Finally, Sect. 5 provides a summary and discusses the implications of the results for future research.

2.1 GMWR observation

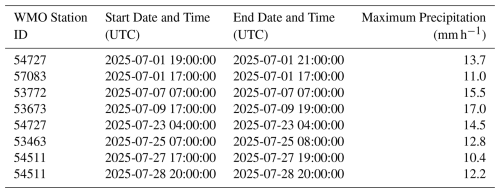

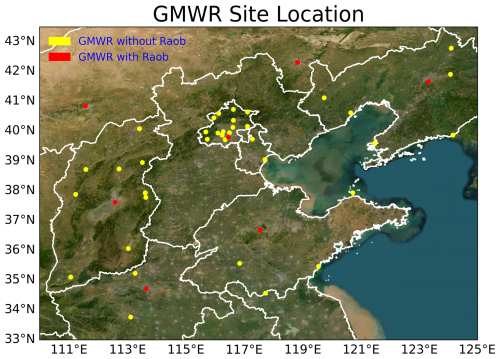

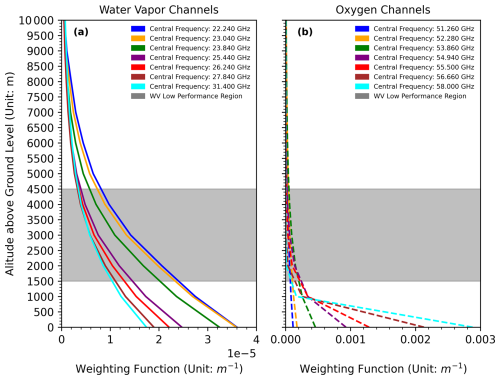

In the North China region, the GMWRs deployed at different sites originate from various manufacturers, yet their channel configurations are consistent. Each instrument is equipped with seven water vapor channels (22.240, 23.040, 23.840, 25.440, 26.240, 27.840, and 31.400 GHz) and seven oxygen channels (51.260, 52.280, 53.860, 54.940, 55.500, 56.660, and 58.000 GHz), dedicated to observing the vertical distribution of atmospheric water vapor and temperature, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates the spatial distribution of GMWRs across North China: in total, 44 stations are equipped with GMWRs under the supervision of the CMA, among which 7 stations are co-located with conventional radiosonde launches. Simulated brightness temperatures, calculated from radiosonde profiles at these 7 stations using the RTTOV-gb (Radiative Transfer for TOVS–ground-based) radiative transfer model (De Angelis et al., 2016; Cimini et al., 2019), were compared with GMWR observations. The results show that GMWR measurements agree well with radiosonde-based simulations under clear-sky and cloudy conditions, while larger discrepancies occur during fog and precipitation events (Fig. 2). Therefore, in this study, all optimal estimation retrievals are restricted to clear-sky and cloudy conditions in order to ensure both retrieval reliability and retrieval applicability.

Figure 1Spatial distribution of ground-based microwave radiometers (GMWRs) in North China. Yellow markers denote stations equipped only with GMWRs, while red markers indicate stations where GMWRs are co-located with radiosonde launches. The topographical basemap is retrieved from ArcGIS Online powered by Esri (Esri et al., 2025).

Figure 2Square root of the error covariance matrices of brightness temperature differences between ground-based microwave radiometer (GMWR) observations and radiosonde-based simulations for different weather conditions: (a) clear-sky conditions, (b) cloudy conditions, (c) fog conditions, and (d) precipitation conditions.

2.2 Radiosonde

Two radiosondes are launched daily from stations 53463, 53772, 54218, 54340, 54511, 54727, and 57083 (red dots in Fig. 1), typically around 23:15 and 11:15 UTC. These routine soundings are employed as reference (“truth”) data for constructing observation error covariance matrices and for evaluating the retrieval accuracy. The radiosondes provide high-quality vertical profiles with well-documented instrumental characteristics: temperature is measured with a resolution of 0.1 K and an accuracy of 0.5 K, relative humidity with a resolution of 1 % and an accuracy of 5 %, and pressure with a resolution of 0.1 hPa and an accuracy of 0.5 hPa (Yao et al., 2025). Such specifications ensure that the radiosonde observations are sufficiently accurate to serve as an independent benchmark against which the ground-based microwave radiometer retrievals can be objectively assessed.

2.3 Hydrometeor profile

To evaluate the performance of the optimal estimation framework for hydrometeor profiling, it is both sufficient and necessary to employ the EarthCARE (Earth Cloud, Aerosol, and Radiation Explorer, Kimura et al., 2003; Donovan et al., 2013; Hélière et al., 2017) cloud retrieval product (CPR_CLD_2A, Mason et al., 2024; Imura et al., 2025; European Space Agency, 2025) as a reference. The active radar observations from EarthCARE provide vertically resolved cloud liquid and ice water content with high sensitivity to optically thick clouds with radar reflective factor target accuracy less than 2.7 dB, which ensures the sufficiency of this dataset as a benchmark for validating the vertical structures. Given the lack of long-term, ground-based observations with comparable vertical resolution and global coverage, the use of CPR_CLD_2A product is also a necessary step to establish the reliability and applicability of the optimal estimation hydrometeor retrievals in a broader context.

2.4 Priori profile

In this study, the a priori atmospheric profile at each GMWR station is derived from the ERA5 reanalysis (Hoffmann et al., 2019; Hersbach et al., 2020; Bell et al., 2021b) using a bilinear interpolation method. ERA5 is widely recognized as one of the most reliable global reanalysis products, providing high temporal (hourly) and spatial (0.25° × 0.25°) resolution fields as well as a consistent assimilation of a large variety of observations. These advantages make ERA5 an appropriate substitute for direct observations in regions or periods where in situ measurements are sparse, discontinuous, or completely unavailable. The use of ERA5 as background information ensures that the constructed priori profiles capture large-scale atmospheric variability with high fidelity, while still allowing the GMWR observations to provide additional fine-scale constraints during the retrieval process.

3.1 1D-Var framework

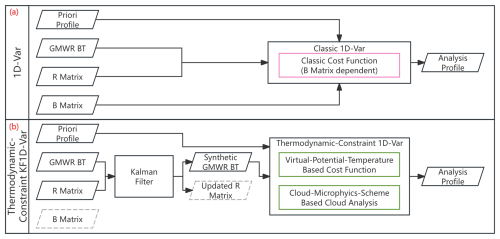

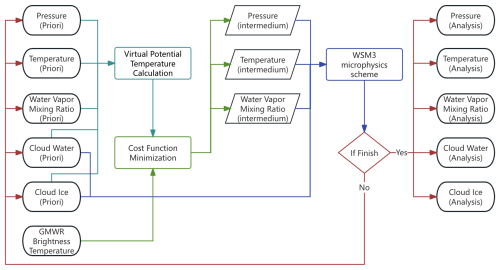

As a widely used approach to retrieve atmospheric state, 1D-Var (Fig. 3a) has been used in thermodynamic profile retrieval systems for both ground-based (Hewison and Gaffard, 2006; Martinet et al., 2017; Gamage et al., 2020), airbone (Thelen et al., 2009; Bell et al., 2021a), and spacebone instruments (Noh et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2024; Carminati, 2022) by minimizing the cost function (Rodgers, 2000) Eq. (1):

where y is the GMWR brightness temperature observation at a given time; R is the observation error covariance matrix; B is the background error covariance matrix; x0 is the priori profile; and H(x) is the observation-operator-simulated brightness temperature corresponding to a given atmospheric state x. In this study, the RTTOV-gb is selected as the observation operator H.

The accuracy of thermodynamic profiles retrieved with the 1D-Var framework depends not only on the measurement precision of the instruments but also on the specification of the background and observation error covariance matrices, which are typically estimated from long-term observational archives. While such climatologically based error covariances can provide overall robust accuracy, their emphasis on representing the mean state reduces the ability of the retrieved optimal profiles to capture rapidly evolving weather phenomena, such as convective system initiation.

3.2 TCKF1D-Var framework

The TCKF1D-Var framework (Fig. 3b) inherits the Kalman filter's capability of reducing random measurement noise by generating synthetic observations (Welch and Bishop, 1995; Foth and Pospichal, 2017; Zhang et al., 2023, 2025) but replaces the cost function of the 1D-Var (Eq. 1) with a thermodynamic-constrained formulation in which the background and observation error covariance matrices are no longer required (Sect. 3.3.1). In addition, a microphysical hydrometeor analysis module (Sect. 3.3.2) is integrated into the 1D-Var framework to enhance the accuracy of the retrieved profiles under cloudy conditions.

3.2.1 Thermodynamic-constrained cost function

Since virtual potential temperature (θv) accounts for the influences of air pressure (P), temperature (T), water vapor (qv), and hydrometeors (ql for cloud liquid water content, qi for cloud ice water content) in its calculation (Eqs. 2 and 3) and is conserved during moist adiabatic processes in the atmosphere (de Haan and van der Veen, 2014; Benjamin et al., 2021), it serves as an ideal control variable in the cost function. In addition, using this control variable not only allows for the adjustment of temperature and humidity profiles based on observations but also enables simultaneous modifications to pressure and hydrometeor profiles. More importantly, compared to classic 1D-Var (Sect. 3.1), this control variable ensures that the retrieved profiles satisfy thermodynamic equilibrium while achieving the mathematical optimum of the cost function.

where Rd is the specific gas constant for dry air, and Cp is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure for dry air.

To eliminate the influence of climatological background and observation error covariance matrices on the retrieved profiles, while ensuring that both the observation and control variable terms in the cost function are dimensionless, we replace the classic difference-based calculation in the cost function with a ratio-based formulation. Additionally, to enhance the contribution of the initial analysis increment to the cost function and reduce the number of iterations, unity (1, in this case) is subtracted from both the observation and control variable terms before squaring. The newly formulated cost function is expressed as in Eq. (4):

Due to the finite precision of floating-point arithmetic, a loss of significant digits may occur, potentially compromising the numerical stability of the computation. To mitigate this issue, both the observed ( and simulated () variables are normalized to the range of −1 to 1 using an amplification factor derived from , where max() and abs() denote the maximum and absolute value operators, respectively. Furthermore, all input values are converted to double precision before the initialization of the minimization algorithm to enhance numerical stability and robustness. To avoid normalization issues when observed and simulated brightness temperatures are very close to each other, the quality control module automatically discards GMWR channel observations whose brightness temperature departures from the simulated values are smaller than the noise-equivalent temperature difference. In addition, the ratio-based cost function provides several advantages over the conventional difference-based formulation used in standard 1D-Var retrievals. It ensures balanced channel weighting, as each channel is normalized by its own magnitude and channels with smaller brightness temperatures are no longer underrepresented during optimization. It also achieves better physical consistency, since the ratio-based form is closer to the logarithmic radiative response of microwave observations, making the inversion more physically meaningful. Finally, it offers enhanced robustness to calibration biases, being less sensitive to multiplicative gain or calibration errors and therefore improving retrieval performance under low signal-to-noise conditions.

3.2.2 Microphysical hydrometeor analysis

While RTTOV-gb incorporates the influence of cloud liquid water in brightness temperature calculations and provides the corresponding Jacobians, the inherently discontinuous vertical structure of clouds in the real atmosphere prevents liquid water profiles from being retrieved in a manner consistent with temperature and humidity profiles. Moreover, RTTOV-gb accounts only for liquid water, neglecting the impact of cloud ice. As a result, constructing the observational term of the cost function solely with RTTOV-gb is insufficient to ensure its physical consistency and closure. Therefore, the inclusion of a cloud microphysics scheme in the cost function is essential to achieve a physically consistent and closed formulation. Considering the trade-off between computational efficiency and simulation accuracy, the WSM3 single-moment microphysics scheme (Hong et al., 2004; Que et al., 2016) is employed as the basis for the diagnostic representation of cloud liquid water and cloud ice profiles. The coupling between the thermodynamic constraint and the WSM3 single-moment microphysics scheme is illustrated in Fig. 4. The procedure begins with the calculation of the virtual potential temperature from the priori thermodynamic and hydrometeor profile. These fields serve as the initial state for the cost function minimization, where the cost function iteratively adjusts the pressure, temperature, and water vapor mixing ratio using the GMWR brightness temperature observations to produce intermedium profiles. The WSM3 microphysics scheme then dynamically updates the cloud water and cloud ice mixing ratios based on the intermediate pressure, temperature, and water vapor profiles, together with the priori hydrometeor fields. This coupling ensures physical consistency between the thermodynamic state and the microphysical processes during each iteration. If the convergence criterion is satisfied, the resulting profiles of temperature, humidity, and hydrometeors are designated as the final analysis. Otherwise, the updated fields are fed back into the next iteration as new initial conditions until convergence is achieved.

Figure 4Schematic of the coupling between the thermodynamic constraint and the WSM3 single-moment microphysics scheme. The cost function iteratively adjusts pressure, temperature, and water vapor using GMWR observations, while WSM3 updates cloud water and ice mixing ratios. The process repeats until convergence, yielding the final analysis of thermodynamic and hydrometeor profiles.

3.3 Cost function minimization

For the three frameworks described above, we employ the L-BFGS method (Limited-memory Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno, Liu and Nocedal, 1989; Byrd et al., 1995) to obtain their optimal estimates. The rationale for choosing this method is as follows: (1) it has low memory requirements, making it suitable for high-dimensional optimization problems; (2) it does not explicitly store the Hessian matrix, but instead approximates it using the gradients and variable changes from the most recent m steps, resulting in fast convergence. In this study, all three frameworks share the same parameter settings: a maximum of 1500 iterations, a cost function convergence tolerance of , a gradient norm convergence tolerance of , and a maximum of 20 line searches per iteration.

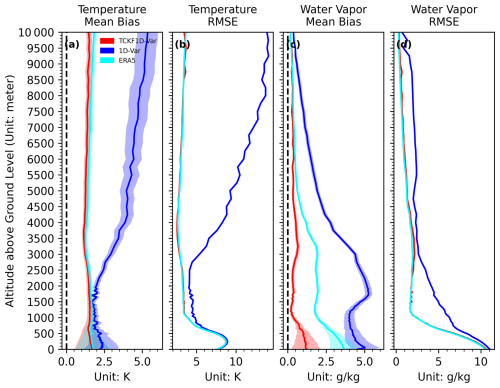

Figure 5Validation of temperature and water vapor profiles retrieved by TCKF1D-Var (red), ERA5 a priori (cyan), and 1D-Var (blue) against radiosonde observations. The shaded areas denote the 95 % confidence intervals that have passed the significance test. For temperature, TCKF1D-Var reduces the mean bias (a) relative to the a priori and yields smaller overall random errors (b) than 1D-Var. For water vapor, TCKF1D-Var substantially decreases the mean bias (c) compared to the a priori, particularly below 5500 m, while its random errors (d) are smaller than 1D-Var near the surface but remain larger than the a priori aloft.

4.1 Thermodynamic profile evaluation

4.1.1 General performance

Figure 5 presents the validation results of TCKF1D-Var and 1D-Var, and the a priori profiles (ERA5) against radiosonde observations. As shown in Fig. 5a, in terms of mean bias, the temperature profiles retrieved by TCKF1D-Var exhibit smaller average errors than the ERA5 a priori profiles, whereas the profiles derived from 1D-Var show larger mean bias than the a priori. This indicates that TCKF1D-Var is capable of effectively correcting the systematic biases in the ERA5 temperature profiles, while the corrections achieved by 1D-Var are less evident. Moreover, the bias reduction provided by TCKF1D-Var is more pronounced in the free atmosphere (above 2000 m) than within the boundary layer (below 2000 m). In terms of root mean square error (RMSE, Fig. 5b), the random errors of the TCKF1D-Var temperature profiles are comparable to those of the ERA5 a priori below 8500 m above ground level, but become larger than the a priori above that level. Nevertheless, the overall random errors of TCKF1D-Var remain smaller than that from 1D-Var, highlighting that the TCKF1D-Var framework, which incorporates virtual potential temperature conservation, is more suitable for tropospheric temperature profile retrievals compared to 1D-Var framework. For water vapor, the improvement in mean bias correction achieved by TCKF1D-Var is even more evident than for temperature (Fig. 5c). Within 0–1000 m, the mean bias of TCKF1D-Var water vapor profiles is below 1.5 g kg−1, whereas the ERA5 a priori bias exceeds 1.5 g kg−1. Between 1000–5500 m, TCKF1D-Var reduces the mean bias to below 0.5 g kg−1, while the ERA5 a priori bias remains between 0.5 and 1.5 g kg−1. In contrast, the water vapor profiles produced by 1D-Var show mean biases consistently larger than 0.5 g kg−1 below 9000 m. These results clearly demonstrate that, relative to 1D-Var, the TCKF1D-Var framework not only provides a more suitable approach for tropospheric temperature retrievals but also substantially reduces the mean bias of a priori water vapor profiles. Regarding RMSE (Fig. 5d), the random errors of water vapor profiles retrieved with TCKF1D-Var are smaller than those of 1D-Var in the 0–1500 m range, but remain larger than the ERA5 a priori. In the 1500–5500 m layer, TCKF1D-Var exhibits the largest RMSE among all products, while in the 5500–10 000 m layer, its random errors are comparable to those of 1D-Var but still higher than those of the a priori.

4.1.2 Day-Night Performance Difference

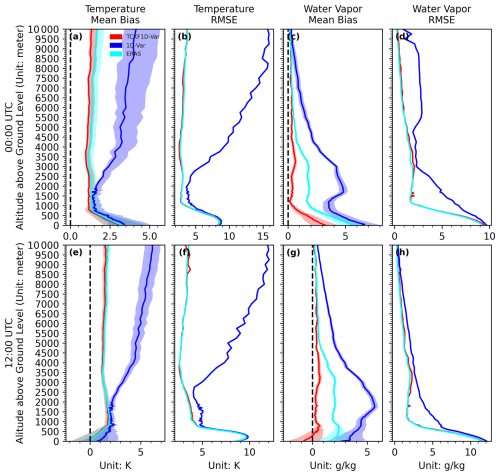

Building on Sect. 4.1.1, we further separate the validation results of the four sets of profiles against radiosonde observations at 00:00 UTC (08:00 BJT) and 12:00 UTC (20:00 BJT) to examine the diurnal variability in the performance of TCKF1D-Var and 1D-Var, and the ERA5 a priori profiles. For temperature mean bias, the differences between the TCKF1D-Var and ERA5 are predominantly limited within the boundary layer, while detectable improvements are found above 3000 m above ground level. As shown in Fig. 6a, at 00:00 UTC, the temperature profiles from TCKF1D-Var exhibit smaller systematic biases than the ERA5 a priori, indicating a more effective correction of the a priori bias, while the 1D-Var bias is larger. At 12:00 UTC (Fig. 6e), both TCKF1D-Var and the a priori show smaller mean biase than 1D-Var. Although the difference between TCKF1D-Var and the a priori becomes less pronounced during daytime, the TCKF1D-Var bias remains lower than that of the a priori. For RMSE, the 00:00 UTC results (Fig. 6b) are generally consistent with those in Sect. 4.1.1. However, at night (Fig. 6f), the random errors of the TCKF1D-Var temperature profiles increase substantially above 8500 m, changing from being comparable to ERA5 during daytime to slightly higher than those of ERA5. Regarding water vapor mean bias (Fig. 6c and g), the diurnal validation results are largely consistent with those in Sect. 4.1.1. The main difference appears below 500 m during nighttime, where, based on the 00:00 UTC radiosondes, TCKF1D-Var shows positive mean bias, while at night the mean bias becomes negative. Similarly, for RMSE (Fig. 6d and h), the overall behavior resembles that in Sect. 4.1.1, with the only notable difference occurring above 5500 m during daytime: based on the 00:00 UTC radiosondes, 1D-Var produces larger random errors than TCKF1D-Var, whereas at night the two are nearly indistinguishable.

Figure 6Validation of temperature and water vapor profiles retrieved by TCKF1D-Var (red), ERA5 a priori (cyan), and 1D-Var (blue) against radiosonde observations at 00:00 UTC (a–d) and 12:00 UTC (e–h). The shaded areas denote the 95 % confidence intervals that have passed the significance test. Panels (a), (e) show mean temperature bias, indicating that TCKF1D-Var provides the most effective correction of systematic errors relative to the a priori. Panels (b), (f) present temperature RMSE, where TCKF1D-Var maintains smaller random errors than 1D-Var during daytime, but shows increased errors above 2000 m at night. Panels (c), (g) show mean water vapor bias, with TCKF1D-Var substantially reducing systematic errors compared to the other methods, while differences between 1D-Var are most evident above 5500 m. Panels (d), (h) depict water vapor RMSE, again showing improved performance of TCKF1D-Var near the surface, with daytime differences between 1D-Var diminishing at night.

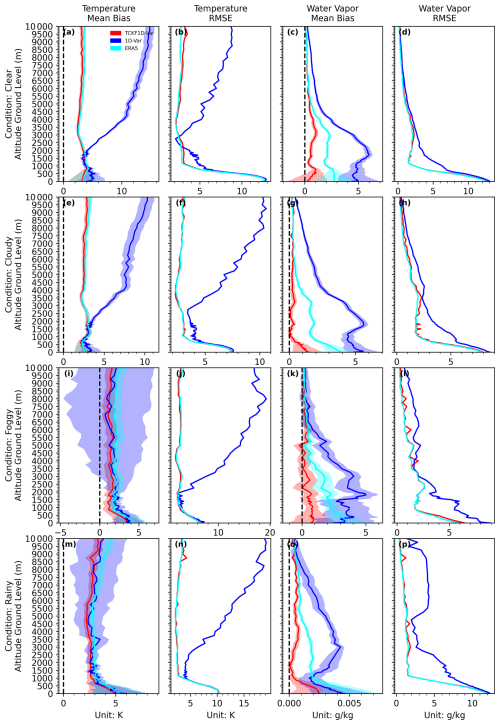

4.1.3 Accuracy under Different Weather Conditions

Under clear-sky and cloudy conditions (Fig. 7a and e), the mean temperature errors are generally consistent with the results in Fig. 5a, with TCKF1D-Var showing smaller biases than both ERA5 (as the background profiles) and 1D-Var. Under foggy (Fig. 7i) and rainy (Fig. 7m) conditions, TCKF1D-Var also exhibits reduced temperature errors below 5 km compared to ERA5 and 1D-Var, while above 5 km its performance is comparable to 1D-Var. In contrast, ERA5 shows similar errors to 1D-Var below 3 km but becomes less accurate above this level. Across all four weather regimes (clear-sky, cloudy, foggy, and rainy), the root-mean-square errors (RMSEs) of the temperature profiles are consistent with Fig. 5b, i.e., TCKF1D-Var performs comparably to ERA5 but clearly outperforms 1D-Var. For water vapor, under clear-sky (Fig. 7c) and cloudy (Fig. 7g) conditions, the mean errors of TCKF1D-Var remain smaller than those of ERA5 and 1D-Var, consistent with the results reported earlier. Under foggy (Fig. 7k) and rainy (Fig. 7o) conditions, TCKF1D-Var again yields smaller mean errors than both ERA5 and 1D-Var, although ERA5 exhibits larger biases than 1D-Var within the boundary layer (below ∼ 500 m in foggy cases and below ∼ 1000 m in rainy cases). In all four weather regimes, the RMSEs of water vapor profiles from TCKF1D-Var are comparable to those of ERA5 and consistently lower than those of 1D-Var.

Figure 7Mean errors (a, e, i, n) and root-mean-square errors (b, f, j, o for temperature; c, g, k, p for water vapor) of retrieved profiles under four weather conditions: clear-sky, cloudy, foggy, and rainy. The shaded areas denote the 95 % confidence intervals that have passed the significance test. TCKF1D-Var consistently shows smaller temperature biases than ERA5 and 1D-Var below 5 km, with performance comparable to ERA5 above this level. ERA5 exhibits higher errors than 1D-Var above 3 km. For water vapor, TCKF1D-Var outperforms both ERA5 and 1D-Var across all regimes, while ERA5 displays larger boundary-layer errors (below ∼ 500 m in foggy cases and below ∼ 1000 m in rainy cases). In all conditions, the RMSEs of TCKF1D-Var are comparable to ERA5 and lower than 1D-Var.

4.1.4 Water Vapor RMSE Deficit Analysis

Despite the overall accuracy improvements achieved by the TCKF1D-Var framework, the retrieved water vapor profiles still exhibit systematic degradation in the middle troposphere (approximately 1.5–4.5 km) from the aspect of RMSE. A primary cause of this problem is the inherent coupling between temperature and humidity signals in the GMWR-measured brightness temperatures. While oxygen channels provide constraints on the temperature structure, their weighting functions peak at vertical levels, calculated by PyRTlib (Python package for non-scattering line-by-line microwave radiative transfer simulations, Larosa et al., 2024) using US Standard Atmosphere profile as background (U.S. Committee on Extension to the Standard Atmosphere, 1976), do not coincide with those of the water vapor channels (Fig. 8). This vertical resolution mismatch leads to a partial leakage of temperature uncertainties into the humidity retrieval, thereby amplifying errors in this altitude range. The effect is particularly pronounced where temperature-sensitive channels show weak sensitivity, while humidity-sensitive channels remain reasonably responsive, leaving the retrieval under-constrained and more dependent on the completeness of the cost function design. Such temperature–humidity coupling has been reported in earlier radiative transfer and retrieval studies (e.g., Hewison, 2007; Löhnert and Maier, 2012), underscoring the necessity of explicitly characterizing vertical resolution mismatches and accounting for cross-variable error propagation when developing retrieval strategies. By contrast, a similar RMSE degradation is not observed in the temperature profiles. This asymmetry arises because the oxygen channels provide stronger and more vertically distinct weighting functions, which dominate the temperature information content and are only weakly influenced by humidity-related uncertainties. Furthermore, humidity channels have comparatively limited indirect sensitivity to temperature, and thus cannot introduce significant contamination into the temperature solution. As a result, the temperature retrieval remains well constrained across the troposphere, preventing the amplification of mid-level RMSE seen in the humidity retrieval.

Figure 8Weighting functions of temperature-sensitive (oxygen) and humidity-sensitive (water vapor) channels calculated with PyRTlib using the US Standard Atmosphere profile (U.S. Committee on Extension to the Standard Atmosphere, 1976) as background. The mismatch in vertical sensitivity between oxygen and water vapor channels is highlighted.

4.2 Hydrometeor Profile Evaluation

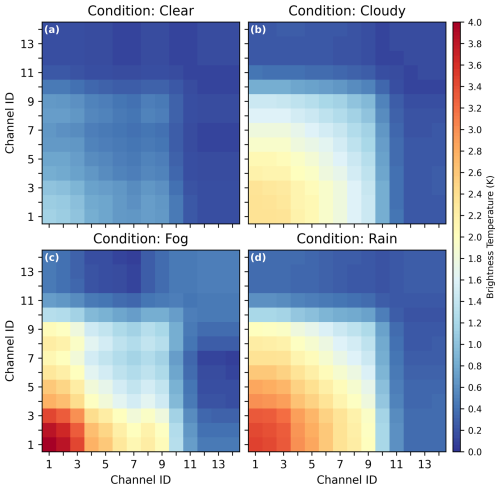

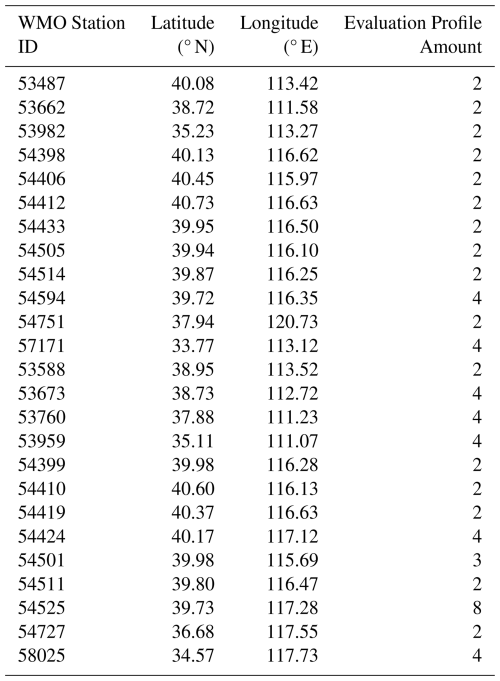

Previous evaluations of temperature and humidity have demonstrated the higher accuracy of the TCKF1D-Var profiles. In this section, we further validate the three retrieval products against the EarthCARE cloud liquid water content (CLWC) observations. The EarthCARE profiles were collocated in time and space by applying the following criterion: if an EarthCARE observation occurred within ±15 min of the profile validation time and within a 15 km radius of the station, the corresponding EarthCARE CLWC profile was used as the reference truth. Table 1 summarizes the number of collocated cases and profiles available in July 2025.

Table 1Summary of collocated EarthCARE cloud liquid water content (CLWC) profiles and corresponding retrieval cases used for validation in July 2025.

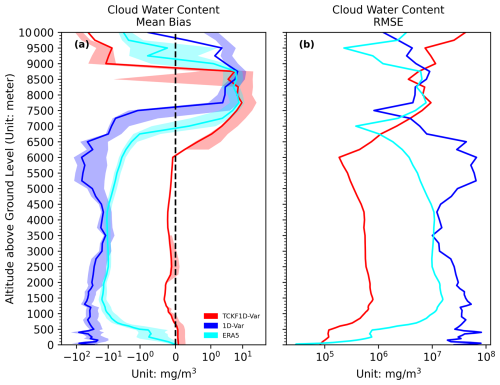

As shown in Fig. 9, the mean errors indicate that the 1D-Var retrieval underestimates LWC by 101–102 mg m−3 relative to EarthCARE in the 0–6 km layer, while ERA5 shows a smaller underestimation of about 100–101 mg m−3. In contrast, TCKF1D-Var exhibits the smallest bias, with deviations consistently within 100 mg m−3 throughout the 0–6 km range. In terms of RMSE, TCKF1D-Var maintains values below 102 mg m−3 across 0–6 km, whereas ERA5 exceeds 102 mg m−3 except below 1 km, and 1D-Var shows the largest errors, remaining in the range of 102–103 mg m−3.

Figure 9Mean error and root-mean-square error (RMSE) of cloud liquid water content (CLWC) profiles from 1D-Var, ERA5, and TCKF1D-Var relative to EarthCARE observations. The shaded areas denote the 95 % confidence intervals that have passed the significance test. The 1D-Var retrievals show the largest underestimation (101–102 mg m−3) and highest RMSE (102–103 mg m−3), ERA5 exhibits smaller biases (100–101 mg m−3) but RMSEs above 102 mg m−3 except below 1 km, while TCKF1D-Var achieves the smallest deviations, with mean errors within 100 mg m−3 and RMSEs consistently below 102 mg m−3.

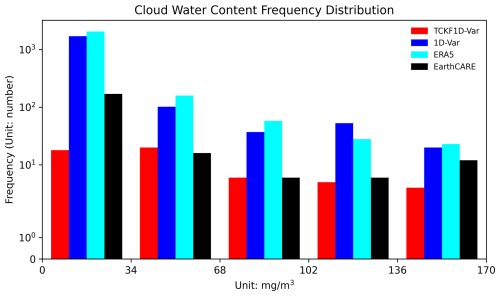

Histogram bins in Fig. 10 are defined to ensure sufficient sample counts in each interval for robust frequency comparisons, following established practice in cloud-microphysics statistical analyses (Zhang et al., 2021; Mroz et al., 2023). The resulting CLWC frequency distributions (Fig. 10) further substantiate the comparative findings: TCKF1D-Var aligns most closely with EarthCARE observations below 136 mg m−3, with particularly strong agreement in the 36–136 mg m−3 range. In the 0–34 mg m−3 interval, TCKF1D-Var differs from EarthCARE by roughly one order of magnitude (101), whereas ERA5 and 1D-Var exhibit discrepancies exceeding 102. For 136–170 mg m−3, the deviations of TCKF1D-Var relative to EarthCARE become comparable to, or slightly larger than, those of ERA5 and 1D-Var.

Figure 10Frequency distribution histograms of cloud liquid water content (CLWC) from 1D-Var, ERA5, and TCKF1D-Var compared with EarthCARE observations. TCKF1D-Var agrees most closely with EarthCARE below 136 mg m−3, particularly in the 36–136 mg m−3 interval. In the 0–34 mg m−3 range, TCKF1D-Var differs from EarthCARE by about one order of magnitude (101), while ERA5 and 1D-Var show larger discrepancies exceeding 102. For 136–170 mg m−3, the deviations of TCKF1D-Var relative to EarthCARE are comparable to, or slightly greater than, those of ERA5 and 1D-Var.

4.3 Extreme precipitation event early-warning capability demonstration

The preceding results demonstrate that the thermodynamic profiles retrieved from TCKF1D-Var framework exhibit smaller mean biases than ERA5, with root-mean-square errors lower than those from 1D-Var and comparable to ERA5, while the retrieved cloud liquid water content shows a higher degree of consistency with EarthCARE observations compared to both 1D-Var and ERA5. To further confirm that these improvements in retrieval accuracy translate into practical benefits, we investigate their implications for the early identification of extreme precipitation signals. Using the criterion of hourly accumulated precipitation exceeding 10 mm to define heavy rainfall events (World Meteorological Organization, 2007), we identified eight short-duration extereme precipitation cases in July 2025 at stations equipped with GMWRs (Table 2). Following the approach proposed by Taylor et al. (2007) and Garcia-Carreras et al. (2010), we adopt the temporal moving anomaly of virtual potential temperature as an early-warning indicator, which removes slowly varying background signals associated with large-scale processes and diurnal variations. Using the selected precipitation cases, we analyze the time series derived from different profile products and evaluate its relationship with the onset of heavy rainfall events. The temporal deviation of virtual potential temperature is calculated as follows:

where is the temporal moving anomaly of virtual potential temperature, is the virtual potential temperature at observation time T0, is the virtual potential temperature at time t within the time window of Window size.

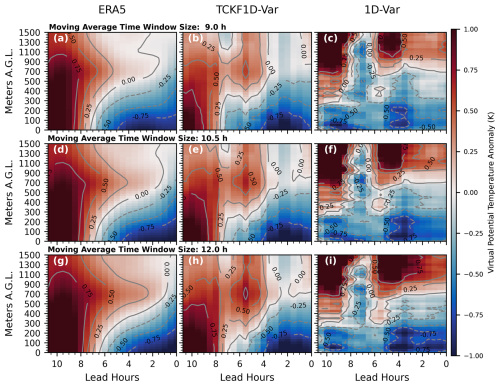

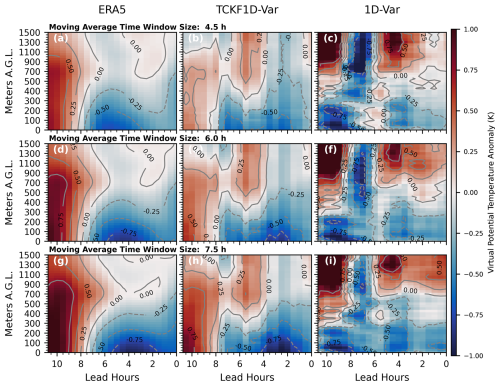

Figure 11 presents the case-averaged time–height evolution of the virtual potential temperature anomaly derived from ERA5 (Fig. 11a, d, and g), TCKF1D-Var (Fig. 11b, e, and h), and 1D-Var (Fig. 11c, f, and i) under different temporal averaging windows: 9.0 h (Fig. 11a, b, and c), 10.5 h (Fig. 11d, e, and f), and 12.0 h (Fig. 11g, h, and i), spanning from 11 h prior to the onset of precipitation to the time of rainfall occurrence. From the ERA5 profiles, a distinct signal emerges below 400 m, where the anomaly changes from positive to negative during the 11 h preceding precipitation, accompanied by the intrusion of a warm anomaly tongue between 400 and 1100 m. Taking the transition from +0.25 to −0.25 K as the early-warning threshold, ERA5 allows the identification of heavy rainfall 6–7 h in advance. When using the criterion of the anomaly dropping below −0.75 K as a secondary trigger, ERA5 can reconfirm the occurrence of heavy rainfall 4–5 h ahead. The TCKF1D-Var retrievals reproduce these key precursory features, namely the positive-to-negative anomaly transition and the warm tongue intrusion, with an even stronger signal compared to ERA5. Based on the +0.25 to −0.25 K transition, TCKF1D-Var indicates the potential onset of heavy rainfall 7.5–8.0 h in advance, while the secondary threshold of −0.75 K enables a reconfirmation 4.0–4.5 h before the event. By contrast, the 1D-Var profiles fail to capture the anomaly transition and warm tongue intrusion in the pre-precipitation stage, and the +0.25 to −0.25 K transition cannot be identified as a reliable precursor. Moreover, when adopting the −0.75 K criterion, the 1D-Var time–height series exhibits two spurious anomaly layers, leading to an increased false-alarm rate. In summary, the TCKF1D-Var framework enhances the representation of vertical atmospheric structures relevant to heavy rainfall initiation, such as the temporal evolution of virtual potential temperature anomalies and warm tongue intrusions, thereby providing a slightly longer lead time for early-warning signals compared to ERA5, whereas such improvements are absent in the 1D-Var results. Using the same methodology, we recalculated the time–height evolution of the virtual potential temperature anomaly with a reduced temporal averaging window (Fig. A1 in Appendix A), and the gradients of the anomaly variations become weaker compared to those in Fig. 11, owing to the shorter averaging window. Nevertheless, both ERA5 and TCKF1D-Var profiles still exhibit the characteristic transition of the anomaly from positive to negative about 7–8 h prior to rainfall onset. Although the warm anomaly tongue intrusion remains detectable in both products, its intensity is reduced. When adopting −0.75 K as the early-warning threshold, the signal becomes indistinct under the 4.5 h averaging window, whereas it is enhanced and temporally stabilized within about 2 h of the precipitation onset when using 6.0 and 7.5 h windows. Consistent with the previous findings, the 1D-Var (Fig. A1c, f, and i) profiles fail to extract effective early-warning signals for heavy rainfall.

Figure 11Case-averaged time–height evolution of virtual potential temperature anomalies derived from ERA5 (a, d, g), TCKF1D-Var (b, e, h), and 1D-Var (c, f, i) under different temporal averaging windows of 9.0 h (a–c), 10.5 h (d–f), and 12.0 h (g–i), spanning from 11 h before to the onset of precipitation. ERA5 and TCKF1D-Var reveal the positive-to-negative anomaly transition below 400 m and the warm anomaly tongue intrusion between 400–1100 m, serving as precursors of heavy rainfall. Compared to ERA5, TCKF1D-Var provides stronger signals and longer lead times (7.5–8.0 h), whereas 1D-Var fails to capture these features and exhibits spurious anomaly layers under the −0.75 K criterion.

This study introduces and evaluates TCKF1D-Var, a thermodynamic-constrained Kalman-filter/1D-variational framework to retrieve temperature, water vapor, and hydrometeor profiles from ground-based microwave radiometers (GMWRs). Designed to overcome classical 1D-Var weaknesses in cloudy conditions, TCKF1D-Var enforces moist-thermodynamic consistency and closes the retrieval with a simple single-moment microphysics (WSM3), linking the state vector to cloud liquid/ice water. Its cost function is reformulated as a dimensionless ratio, removing explicit dependence on climatological background and observation error covariances and preserving rapidly evolving signals. Key methodological innovations are: (1) using virtual potential temperature (θv) as the control variable so temperature, humidity, pressure and hydrometeors adjust jointly under moist-adiabatic constraints; (2) adopting a ratio-based cost function to avoid suppressing transient features by mis-specified matrices; and (3) adding a diagnostic microphysics closure to capture vertical hydrometeor structure when RTTOV-gb radiative transfer alone is insufficient.

A North China deployment of 44 GMWR sites (seven with collocated radiosondes) shows consistent gains. Relative to ERA5 and a classical 1D-Var, TCKF1D-Var substantially reduces systematic biases in temperature and humidity (largest temperature bias reductions above ∼ 2 km; strongest humidity bias reductions from the surface to ∼ 5.5 km). Temperature RMSE is comparable to ERA5 and lower than 1D-Var below ∼ 8.5 km. Humidity RMSE is improved over 1D-Var in the near-surface layer (0–1.5 km) but is larger than ERA5 aloft – an issue diagnosed below. Hydrometeor validation against collocated EarthCARE cloud liquid water content profiles (±15 min, 15 km; July 2025) finds TCKF1D-Var produces the smallest biases and lowest RMSE, and best reproduces EarthCARE distributions in the 36–136 mg m−3 range. The collocation sample is modest and seasonally limited, so broader validation is needed. In application to eight short-duration extreme precipitation events (WMO ≥ 10 mm h−1), TCKF1D-Var strengthens precursory θv signals and lengthens first-alert lead time from ∼ 6–7 h (ERA5) to ∼ 7.5–8 h while retaining the ∼ 4–4.5 h reconfirmation window; 1D-Var often fails to capture robust precursors.

A focused “RMSE deficit” analysis attributes mid-tropospheric humidity degradation to vertical-resolution mismatch and cross-talk between oxygen (temperature-sensitive) and water-vapor channels: misaligned weighting-function peaks permit temperature uncertainty to leak into humidity retrievals, especially in the ∼ 1.5–4.5 km layer. This highlights an intrinsic limitation of passive microwave profiling and motivates explicit cross-covariance handling or multi-sensor synergy (e.g., lidar, cloud radar). We also acknowledge that the performance of the classical 1D-Var approach is inherently shaped by the prescribed background (B) and observation (R) error covariance matrices, and the differences highlighted in this study should not be interpreted as a universal limitation. Rather than positioning TCKF1D-Var as a replacement for 1D-Var, our intention is to provide a complementary retrieval framework that incorporates moist-thermodynamic constraints and a microphysical closure, features that are not explicitly represented in the classical formulation. The evaluation sites in North China exhibit regional characteristics, and it is fully plausible that in regimes with weaker humidity gradients or reduced baroclinicity, 1D-Var may perform similarly or even more favourably. Radiosonde observations remain an essential benchmark for upper-air thermodynamic verification, and to address the limited availability of co-located soundings, additional comparisons with ERA5 were included. Overall, the combined evaluation suggests that TCKF1D-Var can extract additional thermodynamic information from GMWR measurements and thus serves as a useful complement to existing 1D-Var techniques under the conditions examined. These considerations have been incorporated to ensure that the inter-method comparison is presented within a balanced and context-appropriate framework.

Nevertheless, This study demonstrates that the TCKF1D-Var framework efficiently integrates thermodynamic constraints and microphysical closure into a unified variational retrieval system, substantially reducing biases, improving hydrometeor profile realism, and enhancing heavy-rain precursor detection. These results highlight its potential for continuous GMWR profiling and short-range nowcasting applications. However, current validation relies on about 60 collocated EarthCARE profiles from July 2025, which limits the statistical robustness of hydrometeor evaluation and the representativeness of seasonal variability. July was selected as the initial test period because the prevailing synoptic conditions over North China frequently give rise to a wide range of convective systems, providing a favorable environment for evaluation; nevertheless, extending the experimental period remains necessary to ensure more robust and statistically representative results. Future work will extend evaluations across seasons and regions, employ more advanced microphysics and Bayesian uncertainty quantification, and incorporate multi-sensor fusion and scattering-aware radiative operators to further improve retrieval robustness and operational applicability.

Figure A1Case-averaged time–height evolution of virtual potential temperature anomalies derived from ERA5 (a, d, g), TCKF1D-Var (b, e, h), and 1D-Var (c, f, i) under reduced temporal averaging windows of 4.5 h (a–c), 6.0 h (d–f), and 7.5 h (g–i). Compared to Fig. 10, anomaly gradients weaken with shorter windows; however, ERA5 and TCKF1D-Var still capture the positive-to-negative transition ∼ 7–8 h before rainfall onset and the warm anomaly tongue intrusion, albeit with reduced intensity. The −0.75 K early-warning signal is indistinct for the 4.5 h window but becomes clearer and more temporally stable (∼ 2 h offset) for the 6.0 and 7.5 h windows, while 1D-Var fails to provide effective precursors.

The TCKF1D-Var framework source code is openly available at GitHub (https://github.com/smft/TCKF1D-Var, last access: 14 January 2026) under the GNU Affero General Public License (AGPL). The exact version of the code used to produce the results presented in this study is archived on Zenodo (Zhang, 2025b; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17293102).

The input data required by the TCKF1D-Var framework are available on Zenodo (Zhang, 2025a, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17296305). The TCKF1D-Var thermodynamic and hydrometeor profile dataset generated in this study is also archived on Zenodo (Zhang, 2025c, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17083973). All datasets are publicly available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

JPG and TMC planned the measurement campaign. TMC, YW, YW, JJY and BD conducted the ground-based observations. QZ developed the TCKF1D-Var framework, performed the coding and data analysis, and prepared the manuscript. TMC revised the manuscript. JPG, QZ, and TMC provided funding.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We sincerely thank the handling editor, Cenlin He, for his guidance and oversight throughout the review process. We are also grateful to Juan Antonio Añel for his valuable insights and constructive comments during the interactive public discussion. Furthermore, we extend our appreciation to the two anonymous referees for their thorough and thoughtful reviews, which significantly helped us to improve the quality of this manuscript.

This research is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China under grant 2024YFC3013001, the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant 42325501, the Heavy Rainfall Research Foundation of China under grant BYKJ2025M24, and the Basic Research Fund of CAMS under grant 2024Z003.

This paper was edited by Cenlin He and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Adler, B., Wilczak, J. M., Bianco, L., Djalalova, I., Duncan Jr., J. B., and Turner, D. D.: Observational case study of a persistent cold air pool and gap flow in the Columbia River Basin, Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 60, 1071–1090, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAMC-D-21-0013.1, 2021.

Barrera-Verdejo, M., Crewell, S., Löhnert, U., Orlandi, E., and Di Girolamo, P.: Ground-based lidar and microwave radiometry synergy for high vertical resolution absolute humidity profiling, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 9, 4013–4028, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-9-4013-2016, 2016.

Bell, A., Martinet, P., Caumont, O., Vié, B., Delanoë, J., Dupont, J.-C., and Borderies, M.: W-band radar observations for fog forecast improvement: an analysis of model and forward operator errors, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 14, 4929–4946, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-14-4929-2021, 2021a.

Bell, B., Hersbach, H., Simmons, A., Berrisford, P., Dahlgren, P., Horányi, A., Muñoz-Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Radu, R., Schepers, D., and Soci, C.: The ERA5 global reanalysis: Preliminary extension to 1950, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 147, 4186–4227, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.4174, 2021b.

Benjamin, S. G., James, E. P., Hu, M., Alexander, C. R., Ladwig, T. T., Brown, J. M., Weygandt, S. S., Turner, D. D., Minnis, P., and Smith Jr., W. L.: Stratiform cloud-hydrometeor assimilation for HRRR and RAP model short-range weather prediction, Monthly Weather Review, 149, 2673–2694, https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-20-0385.1, 2021.

Byrd, R. H., Lu, P., and Nocedal, J.: A Limited Memory Algorithm for Bound-Constrained Optimization, SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput., 16, 1190–1208, 1995.

Carminati, F.: A channel selection for the assimilation of CrIS and HIRAS instruments at full spectral resolution, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 148, 1092–1112, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.4248, 2022.

Christofilakis, V., Tatsis, G., Chronopoulos, S. K., Sakkas, A., Skrivanos, A. G., Peppas, K. P., Nistazakis, H. E., Baldoumas, G., and Kostarakis, P.: Earth-to-earth microwave rain attenuation measurements: A survey on the recent literature, Symmetry, 12, 1440, https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12091440, 2020.

Cimini, D., Hocking, J., De Angelis, F., Cersosimo, A., Di Paola, F., Gallucci, D., Gentile, S., Geraldi, E., Larosa, S., Nilo, S., Romano, F., Ricciardelli, E., Ripepi, E., Viggiano, M., Luini, L., Riva, C., Marzano, F. S., Martinet, P., Song, Y. Y., Ahn, M. H., and Rosenkranz, P. W.: RTTOV-gb v1.0 – updates on sensors, absorption models, uncertainty, and availability, Geosci. Model Dev., 12, 1833–1845, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-1833-2019, 2019.

De Angelis, F., Cimini, D., Hocking, J., Martinet, P., and Kneifel, S.: RTTOV-gb – adapting the fast radiative transfer model RTTOV for the assimilation of ground-based microwave radiometer observations, Geosci. Model Dev., 9, 2721–2739, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-2721-2016, 2016.

de Haan, S. and van der Veen, S. H.: Cloud initialization in the Rapid Update Cycle of HIRLAM, Weather and Forecasting, 29, 1120–1133, https://doi.org/10.1175/WAF-D-13-00071.1, 2014.

Donovan, D. P., Barker, H. W., Hogan, R. J., Wehr, T., Eisinger, M., Lajas, D., Lefebvre, A., and EarthCARE Phase-B ESA/JAXA Mission Advisory Group: Scientific aspects of the Earth Clouds, Aerosols, and Radiation Explorer (EarthCARE) mission, AIP Conf. Proc., 1531, 444–447, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4804793, 2013.

Ebell, K., Löhnert, U., Päschke, E., Orlandi, E., Schween, J. H., and CrewellS, S.: A 1-D variational retrieval of temperature, humidity, and liquid cloud properties: performance under idealized and real conditions, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 122, 1746–1766, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JD025945, 2017.

Esri, DeLorme, HERE, TomTom, Intermap, increment P Corp., GEBCO, USGS, FAO, NPS, NRCAN, GeoBase, IGN, Kadaster NL, Ordnance Survey, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), swisstopo, MapmyIndia, and the GIS User Community: World Imagery, https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=10df2279f9684e4a9f6a7f08febac2a9 (last access: 14 January 2026), 2025.

European Space Agency: EarthCARE CPR CLD Level 2A (version AB), European Space Agency [data set], https://doi.org/10.57780/eca-e6471c5, 2025.

Foth, A. and Pospichal, B.: Optimal estimation of water vapour profiles using a combination of Raman lidar and microwave radiometer, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 10, 3325–3344, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-10-3325-2017, 2017.

Gamage, S. M., Sica, R. J., Martucci, G., and Haefele, A.: A 1D-Var retrieval of relative humidity using the ERA5 dataset for the assimilation of Raman lidar measurements, Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 37, 2051–2064, https://doi.org/10.1175/JTECH-D-19-0170.1, 2020.

Garcia-Carreras, L., Parker, D. J., Taylor, C. M., Reeves, C. E., and Murphy, J. G.: Impact of mesoscale vegetation heterogeneities on the dynamical and thermodynamic properties of the planetary boundary layer, J. Geophys. Res., 115, D03102, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JD012811, 2010.

Geerts, B., Parsons, D., Ziegler C., Weckwerth, T., Biggerstaff, M., Clark, R., Coniglio, M., Demoz, B., Ferrare, R., Gallus Jr., W., Haghi, K., Hanesiak, J., Klein, P., Knupp, K., Kosiba, K., McFarquhar, G., Moore, J., Nehrir, A., Parker, M., Pinto, J., Rauber, R., Schumacher, R., Turner, D., Wang, Q., Wang, X., Wang Z., and Wurman, J.: The 2015 Plains Elevated Convection At Night field project. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 98, 767–786, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-15-00257.1, 2017.

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Hirahara, S., Horányi, A., Muñoz-Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Abdalla, S., Abellan, X., Balsamo, G., Bechtold, P., Biavati, G., Bidlot, J., Bonavita, M., De Chiara, G., Dahlgren, P., Dee, D., Diamantakis, M., Dragani, R., Flemming, J., Forbes, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A., Haimberger, L., Healy, S., Hogan, R. J., Hólm, E., Janisková, M., Keeley, S., Laloyaux, P., Lopez, P., Lupu, C., McNally, A., Miranda, P., Monge-Sanz, B. M., Morcrette, J.-J., Müller, M., Penney, S., de Rosnay, P., Rozum, I., Vamborg, F., Villaume, S., and Thépaut, J.-N.: The ERA5 global reanalysis, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803, 2020.

Hewison, T. J.: 1D-VAR retrieval of temperature and humidity profiles from a ground-based microwave radiometer, IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., 45, 2163–2168, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2007.898091, 2007.

Hewison, T. J. and Gaffard, C.: 1D-Var retrieval of temperature and humidity profiles from ground-based microwave radiometers, 2006 IEEE MicroRad, San Juan, Puerto Rico, USA, 28 February–3 March 2006, 235–240, https://doi.org/10.1109/MICRAD.2006.1677095, 2006.

Hoffmann, L., Günther, G., Li, D., Stein, O., Wu, X., Griessbach, S., Heng, Y., Konopka, P., Müller, R., Vogel, B., and Wright, J. S.: From ERA-Interim to ERA5: the considerable impact of ECMWF's next-generation reanalysis on Lagrangian transport simulations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 3097–3124, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-3097-2019, 2019.

Hong, S.-Y., Dudhia, J., and Chen, S.-H.: A revised approach to ice microphysical processes for the bulk parameterization of clouds and precipitation, Mon. Weather Rev., 132, 103–120, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(2004)132<0103:ARATIM>2.0.CO;2, 2004.

Hu, J., N. Yussouf, D. D. Turner, T. A. Jones, and X. Wang: Impact of ground-based remote sensing boundary layer observations on short-term probabilistic forecasts of a tornadic supercell event, Weather and Forecasting, 34, 1453–1476, https://doi.org/10.1175/WAF-D-18-0200.1, 2019.

Hélière, A., Wallace, K., Pereira Do Carmo, J., and Lefebvre, A.: Earth cloud, aerosol, and radiation explorer optical payload development status, Proc. SPIE, Sensors, Systems, and Next-Generation Satellites XXI, 10423, 8–25, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2274704, 2017.

Imura, Y., Tomita, E., Nio, T., Okada, K., Maruyama, K., Nakatsuka, H., Tomiyama, N., Aida, Y., Haze, K., Ochiai, S., Konoue,K., Kubota, T., Tanaka, T., Muto, M., Aoki, S., Horie, H., Ohno, Y., and Sato, K.: EarthCARE/CPR current conditions and preliminary results from scientific views, Proc. SPIE, Remote Sensing of the Atmosphere, Clouds, and Precipitation VIII, 13262, 1326202, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3045833, 2025.

Kimura, T., Kondo, K., Kumagai, H., Kuroiwa, H., Ishida, C., Oki, R., and Nakajima, T.: EarthCARE – Earth Clouds, Aerosol, and Radiation Explorer: its objectives and Japanese sensor designs, Proc. SPIE, Remote Sensing of Clouds and the Atmosphere VII, 4882, 510–519, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.469725, 2003.

Kummerow, C., Olson, W. S., and Giglio, L.: A simplified scheme for obtaining precipitation and vertical hydrometeor profiles from passive microwave sensors, IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., 34, 1213–1232, https://doi.org/10.1109/36.536538, 2022.

Larosa, S., Cimini, D., Gallucci, D., Nilo, S. T., and Romano, F.: PyRTlib: an educational Python-based library for non-scattering atmospheric microwave radiative transfer computations, Geosci. Model Dev., 17, 2053–2076, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-2053-2024, 2024.

Li, Q., Wei, M., Wang, Z., and Chu, Y.: Evaluation and improvement of the quality of ground-based microwave radiometer clear-sky data, Atmosphere, 12, 435, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos12040435, 2021.

Liu, D. and Nocedal, C. J.: On the Limited Memory Method for Large Scale Optimization, Math. Program., 45B, 503–528, 1989.

Löhnert, U. and Maier, O.: Operational profiling of temperature using ground-based microwave radiometry at Payerne: prospects and challenges, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 5, 1121–1134, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-5-1121-2012, 2012.

Martinet, P., Cimini, D., De Angelis, F., Canut, G., Unger, V., Guillot, R., Tzanos, D., and Paci, A.: Combining ground-based microwave radiometer and the AROME convective scale model through 1DVAR retrievals in complex terrain: an Alpine valley case study, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 10, 3385–3402, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-10-3385-2017, 2017.

Mason, S. L., Barker, H. W., Cole, J. N. S., Docter, N., Donovan, D. P., Hogan, R. J., Hünerbein, A., Kollias, P., Puigdomènech Treserras, B., Qu, Z., Wandinger, U., and van Zadelhoff, G.-J.: An intercomparison of EarthCARE cloud, aerosol, and precipitation retrieval products, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 17, 875–898, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-17-875-2024, 2024.

Mroz, K., Treserras, B. P., Battaglia, A., Kollias, P., Tatarevic, A., and Tridon, F.: Cloud and precipitation microphysical retrievals from the EarthCARE Cloud Profiling Radar: the C-CLD product, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 16, 2865–2888, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-16-2865-2023, 2023.

Noh, Y., Huang, H., and Goldberg, M. D.: Refinement of CrIS channel selection for global data assimilation and its impact on the global weather forecast, Weather and Forecasting, 36, 1405–1429, https://doi.org/10.1175/WAF-D-21-0002.1, 2021.

Que, L. J., Que, W. L., and Feng, J. M.: Intercomparison of different physics schemes in the WRF model over the Asian summer monsoon region, Atmos. Oceanic Sci. Lett., 9, 169–177, https://doi.org/10.1080/16742834.2016.1158618, 2016.

Rodgers, C. D.: Inverse methods for atmospheric sounding: Theory and practice. Vol. 2. World Scientific, ISBN 981022740X, 2000.

Taylor, C. M., Parker, D. J., and Harris, P. P.: An observational case study of mesoscale atmospheric circulations induced by soil moisture, Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L15801, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL030572, 2007.

Teixeira, J., Piepmeier, J. R., Nehrir, A. R., Ao, C. O., Chen, S. S., Clayson, C. A., Fridlind, A. M., Lebsock, M., McCarty, W., Salmun, H., Santanello, J. A., Turner, D. D., Wang, Z., and Zeng, X.: Toward a global planetary boundary layer observing system: A summary, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-23-0228.1, 2025.

Thelen, J.-C., Havemann, S., Newman, S. M. and Taylor, J. P.: Hyperspectral retrieval of land surface emissivities using ARIES, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 135, 2110–2124, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.520, 2009.

Turner, D. D. and Löhnert, U.: Ground-based temperature and humidity profiling: combining active and passive remote sensors, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 14, 3033–3048, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-14-3033-2021, 2021.

U.S. Committee on Extension to the Standard Atmosphere: U.S. Standard Atmosphere, 1976, NOAA–S/T 76-1562, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Washington, D.C., USA, https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/stp/space-weather/online-publications/miscellaneous/us-standard-atmosphere-1976/us-standard-atmosphere_st76-1562_noaa.pdf (last access: 14 January 2026), 1976.

Viggiano, M., Cimini, D., De Natale, M. P., Di Paola, F., Gallucci, D., Larosa, S., and Romano, F.: Combining passive infrared and microwave satellite observations to investigate cloud microphysical properties: A review, Remote Sens., 17, 337, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17020337, 2025.

Wagner, T. J., Klein, P. M., and Turner, D. D.: A new generation of ground-based mobile platforms for active and passive profiling of the boundary layer, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 100, 137–153, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-17-0165.1, 2019.

Wang, K.-N., Ao, C. O., Morris, M. G., Hajj, G. A., Kurowski, M. J., Turk, F. J., and Moore, A. W.: Joint 1DVar retrievals of tropospheric temperature and water vapor from Global Navigation Satellite System radio occultation (GNSS-RO) and microwave radiometer observations, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 17, 583–599, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-17-583-2024, 2024.

Weisz, E., Smith Sr., W. L., and Smith, N.: Advances in simultaneous atmospheric profile and cloud parameter regression-based retrieval from high-spectral resolution radiance measurements, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 118, 6433–6443, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50521, 2013.

Welch, G. and Bishop, G.: An Introduction to the Kalman Filter, TR 95-041, Department of Computer Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, https://www.cs.unc.edu/~welch/media/pdf/kalman_intro.pdf (last access: 14 January 2026), 2006.

World Meteorological Organization (WMO): WMO Technical Document No. 1390, World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, https://library.wmo.int/viewer/40422/?offset=#page=1&viewer=picture&o=bookmark&n=0&q= (last access: 14 January 2026), 2007.

Wulfmeyer, V., Hardesty, R. M., Turner, D. D., Behrendt, A., Cadeddu, M., Di Girolamo, P., Schluessel, P., van Baelen, J., and Zus, F.: A review of the remote sensing of lower-tropospheric thermodynamic profiles and its indispensable role for the understanding and simulation of water and energy cycles, Reviews of Geophysics, 53, 819–895, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014RG000476, 2015.

Xu, G.: A review of remote sensing of atmospheric profiles and cloud properties by ground-based microwave radiometers in central China, Remote Sensing, 16, 966, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs16060966, 2024.

Yao, L., Shen, D., Sun, X., Wang, D., Cao, X., Wang, J., Wang, D., Zhang, C., and Guo, Q.: The Beidou Navigation Radiosonde Observation Experiment and Data Evaluation, SSRN [preprint], https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5085235, 2025.

Zhang, L., Ma, Y., Lei, L., Wang, Y., Jin, S., and Gong, W.: Improving atmospheric temperature and relative humidity profiles retrieval based on ground-based multichannel microwave radiometer and millimeter-wave cloud radar, Atmosphere, 15, 1064, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15091064, 2024.

Zhang, Q.: Input Data for TCKF1D-Var framework, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17296305, 2025a.

Zhang, Q.: TCKF1D-Var framework, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17293102, 2025b.

Zhang, Q.: TCKF1D-Var thermodynamic and hydrometeor profile dataset, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17083973, 2025c.

Zhang, Q., Smith Sr., W., and Shao, M.: The potential of monitoring carbon dioxide emission in a geostationary view with the GIIRS meteorological hyperspectral infrared sounder, Remote Sensing, 15, 886, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15040886, 2023.

Zhang, Q., Deng, B., Wang, S., Dong, F., and Shao, M.: Multi-Source Retrieval of Thermodynamic Profiles from an Integrated Ground-Based Remote Sensing System Using an EnKF1D-Var Framework, Remote Sensing, 17, 3133, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17183133, 2025.

Zhang, Y., Chen, S., Tan, W., Chen, S., Chen, H., Guo, P., Sun, Z., Hu, R., Xu, Q., Zhang, M., Hao, W., and Bu, Z.: Retrieval of Water Cloud Optical and Microphysical Properties from Combined Multiwavelength Lidar and Radar Data, Remote Sens., 13, 4396, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13214396, 2021.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Data

- Methods

- Results and disscussion

- Summary and concluding remarks

- Appendix A: Sensitivity of virtual potential temperature anomaly to temporal averaging window

- Code availability

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Data

- Methods

- Results and disscussion

- Summary and concluding remarks

- Appendix A: Sensitivity of virtual potential temperature anomaly to temporal averaging window

- Code availability

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References