the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

A new sub-chunking strategy for fast netCDF-4 access in local, remote and cloud infrastructures, chunkindex V1.1.0

Cédric Penard

Flavien Gouillon

Xavier Delaunay

Sylvain Herlédan

NetCDF (Network Common Data Form) is a self-describing, portable and platform-independent format for array-oriented scientific data which has become a community standard for sharing measurements and analysis results in the fields of oceanography, meteorology, and space domain.

The volume of scientific data is continuously increasing at a very fast rate and poses challenges for efficient storage and sharing of these data. The object storage paradigm that appeared with cloud infrastructures, can help with data storage and parallel access issues.

The availability of ample network bandwidth within cloud infrastructures allows for the utilization of large amounts of data. Processing data where the data is located is preferable as it can result in substantial resource savings. However, for some use cases downloading data from the cloud is required and results still have to be fetched once processing tasks have been executed on the cloud.

However, networks bandwidth and quality can exhibit significant variations depending on the available resources in different use cases: networks can range from fiber-optic and copper connections to satellite connections with poor reception in degraded conditions on boats, among other scenarios. Therefore, it is crucial for formats and software libraries to be specifically designed to optimize access to data by minimizing the transfer to only what is strictly necessary.

By design, the NetCDF data format offers such capabilities. A netCDF file is composed of a pool of chunks. Each chunk is a small unit of data that is independent and may be compressed. These units of data are read or written in a single I/O operation. In this article, we reuse the notion of sub-chunk introduced in the kerchunk library (Sterzinger et al., 2021): we refer to a sub-chunk as a sub-part of a chunk.

The sub-chunking strategies help reducing the amount of data transferred by splitting netCDF chunks in even smaller unit of data. Kerchunk limits the sub-chunking capability to uncompressed chunks. Our approach goes further: it allows the sub-chunking of compressed chunks by indexing their content. In this context, a new approach has emerged in the form of a library that indexes the content of netCDF-4. This indexing enables the retrieval of sub-chunks without the need to read and decompress the entire chunk. This approach targets access patterns such as time series in netCDF-4 datasets formatted with large chunks and it has the advantage of not requiring the entire file to be reformatted.

This report provides a performance assessment of netCDF-4 datasets for various use cases and conditions: POSIX (see POSIX) and S3 local filesystems, as well as a simulated degraded network connection. The results of this assessment may provide guidance on the most suitable and most efficient library for reading netCDF data in different situations.

Another outcome of this study is the impact of the libraries used to access the data: while extensive existing literature compares different file formats performance (open, read and write), the impact of specific standard libraries remains poorly studied. This study evaluates the performance of four Python libraries (netcdf4-python, xarray, h5py, and a custom chunk-indexing library) for reading parts of the datasets through fsspec or s3fs. To complete the study, a comparison with the cloud-oriented formats Zarr and ncZarr is conducted. Results show that the h5py library provides high efficiency for accessing netCDF-4 formatted files and performance close to Zarr on a S3 server. These results suggest that it may not be necessary to convert netCDF-4 datasets to Zarr when moving to the cloud. This would avoid reformatting petabytes of data and costly adaptation of scientific software.

- Article

(4542 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The netCDF (Network Common Data Form) format is widely used in the field of data science and scientific research. It is highly praised for its ability to store multidimensional datasets, such as climate, oceanographic, meteorological and geospatial data. The performance of the netCDF format is often lauded for its efficient handling of large amounts of data while providing a flexible and extensible structure. It enables quick and efficient data access, making it ideal for applications that require frequent read and write operations. Furthermore, the netCDF format offers compatibility with many common programming languages such as Python, R, MATLAB, and C, easing its integration into existing workflows. This versatility makes it a popular choice among scientists and researchers working with complex and voluminous datasets.

In the past ten years, the size of scientific data has increased so dramatically that storing and disseminating data has become a challenge for data producers. For example, the SWOT (Surface Water and Ocean Topography) project produces 10 TB d−1, leading to almost 4 PB of data per year (SWOT project; SWOT mission, 2024). Nevertheless, cloud infrastructure like Amazon's Simple Storage Service (S3) offers a new type of data storage easing the dissemination and the processing of huge data volumes. It implies new ways of using the data and new libraries to access it.

Transferring large volumes of data within a cloud is reasonable due to cloud services communicating over a local network. Processing the data where it is located should be the preferred method when applicable as it can save a significant amount of resources. Yet, the results still have to be fetched once the processing tasks have been executed. Some use cases even require downloading data from the cloud for processing on the client's site, particularly when it involves integrating confidential data that cannot be transferred to the cloud. The data transfers happen on networks whose capacity and quality can vary by several orders of magnitude (consumer-grade fibre optic and copper connections, satellite connection with poor reception in degraded conditions, e.g. on boats). So, formats and software libraries should optimize access to the data by limiting the transfer to what is strictly necessary. This may be crucial for some use cases where remote access to the data could be difficult, such as on a boat during a sea campaign.

As new formats designed for cloud infrastructures emerged (Durbin et al., 2020), data producers have to take into consideration the performance in their choice of a format. Data producers can also consider reformatting historical netCDF-4 datasets into formats designed for cloud architecture such as Zarr (Miles et al., 2020). In Barciauskas et al. (2023) we can find an overview of the different existing cloud-optimized formats. Several studies compare the performance of Zarr and NetCDF-4 formats. For instance, in Pfander et al. (2021), the authors compare the read times in Java of Zarr, HDF5 and netCDF-4 data. They show that the best-performing format depends on the size of the chunks. In Ambatipudi and Byna (2022), the authors compare the performances of HDF5, Zarr and netCDF-4 format using only one library for each format. They observe that the HDF5 is the most performant format for read/write operations. However, both studies evaluate the formats and libraries performance for datasets on a POSIX file system only. Few studies assess the performance of the netCDF-4 format on cloud infrastructures.

Yet Lopez (2024), Lopez et al. (2025) and Jelenak and Robinson (2023) show that HDF5 based format can be performant on cloud infrastructure. Thus, the netCDF-4 format can already be suitable for cloud storage. Indeed, it offers a chunking feature that splits the data into chunks that are comparable to objects in cloud infrastructures. Then, it is possible to download only the chunks of data that are needed using HTTP byte-range requests and solutions that indexes chunks' location in the file, such as kerchunk (Durant, 2021 and Sterzinger et al., 2021), or other architectures described in Gallagher et al. (2017). This approach is also followed in Marin et al. (2022) for the extraction and analysis of data curated by IMOS (Australia's Integrated Marine Observing System) and published on the AODN (Australian Ocean Data Network) portal. An alternative solution is provided by the OPeNDAP framework (Cornillon et al., 2003). In this solution, a client can ask for a slice of the data. The server reads and decompresses the dataset to send only the requested slice through the network. It is important to note that the OPeNDAP DMR implementation is also an approach to chunk indexing. Moreover, NetCDF-4 is a monolithic format. In HPC centers, this presents an advantage over modular file formats, such as Zarr: it does not create numerous “object data” files that can slow the data access time in some condition (Carval et al., 2023).

This study evaluates the performance for reading datasets in netCDF-4 format, on both local file systems and on cloud-oriented file systems. It compares the performance of different libraries in different use cases and data structures. It also compares the performance of netCDF-4, Zarr and ncZarr formats on S3 storage. Section 2 recalls the chunking principle. It is a key feature offered by the netCDF-4 format for remote data access. Section 2 also describes the file systems, libraries and datasets utilized for the performance comparison. Section 3 introduces our custom chunk-indexing library. This library indexes the content of netCDF-4 datasets to allow requesting sub-chunks, i.e. pieces of data smaller than a chunk, without having to reformat the existing files. This approach targets access patterns such as time series in netCDF-4 datasets formatted with large chunks. Section 4 describes the dataset: two files, one from meteorological model and one from oceanographic model. Section 4 also describes the access patterns used in the experiments. Section 5 provides comparative results for three different configurations: local POSIX, remote POSIX with a degraded network connection and local S3. Finally, Sect. 6 draws the conclusions of this study on the best libraries and formats to choose depending on the conditions and access patterns.

2.1 Chunking in the netCDF-4 format

The netCDF-4 format provides chunking capabilities that are crucial for performance (Lee et al., 2008). Chunking consists of dividing the data into small, independent units called chunks. A chunk is read or written in a single I/O operation. This principle optimizes data retrieval and storage within netCDF-4 formatted files, particularly for large datasets. In netCDF-4, the chunks can be accessed and decompressed individually allowing efficient data access and manipulation. Compressed variables or variables with an unlimited dimension are necessarily chunked. When a request is made to retrieve a specific piece of data from a netCDF-4 file, specifying a specific subset of dimensions, variables, or indices, the netCDF-4 library determines which chunks are necessary to fulfil the request and retrieves only the relevant chunks from the file.

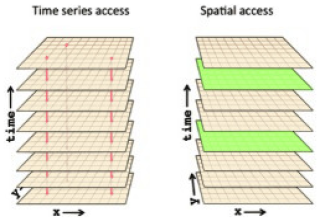

NetCDF-4 provides the capability of automatic chunking. This feature determines a chunking strategy based on the structure and size of the data. However, the chunk size and shape should be chosen taking into account the access patterns, i.e. the various manner the end-user may access the data, in order to minimize the number of disk I/O and the number of decompression operations. For instance, Fig. 1 represents a 3D variable with dimensions (x, y, time). Considering a chunking layout by time frame, i.e. one 2D spatial chunk per time, it would be required to read and inflate all chunks to work on a time series at one given spatial point (left of Fig. 1). However, only one chunk needs to be read and decompressed to work on a spatial frame at a given time t (right of Fig. 1).

It is shown in Lee et al. (2008) that setting a chunk size too small degrades the performance because this implies a large number of read/write operations, especially on large datasets. A chunking pattern cannot be optimal in all situations. The current default chunking strategy of the netCDF-4 library is to balance access time along all variable's dimensions and targets a chunk size lower than 4 MB, well adapted for high performance computing platform.

2.2 File system

Section 4 evaluates the performance of the netCDF-4 format on two kinds of file systems: POSIX (see POSIX certification, 2024) and object storage S3.

POSIX (Portable Operating System Interface, X for UNIX) is a standard created in late 1980s. It aims at being a common standard for all UNIX systems. In POSIX, applications make system calls like open, read or write to communicate with the file system (ext3, ext4, XFS, etc.) through the Linux Kernel and a Virtual File System. This behaviour is defined by the POSIX standard, which serves as the foundational layer of UNIX-like systems. POSIX standard does not only define the file system, but also signals, processes, I/O port interfaces, etc.

S3 is an object storage service that stores data as objects within buckets. A bucket is a container in which objects are stored. Objects are analogous to files in a POSIX file system. S3 is a scalable data storage system. It is optimized for small files and chunks (about 1 MB) to distribute the load on several servers. Object storage in general and S3 in particular has become very popular. It is used for websites, media and data storage. This popularity is mainly due to its simplicity and cost effectiveness.

However, S3 is not POSIX compliant. Unlike POSIX file systems, which support hundreds of commands for file manipulation, S3 offers only a limited set of operations for interacting with objects. S3 introduces a new paradigm in data management. Each object exists in a flat namespace (within a bucket) with a unique identifier. There is no notion of directories in S3. Unlike POSIX storage, which offers byte-level access, S3 provides object-level access. However, S3 APIs support HTTP range requests, allowing partial object reads without downloading the entire object. This is why applications often need to be rewritten or redesigned to efficiently use S3 storage.

In our tests, we use the GPFS storage of the TREX cluster at CNES, as well as the CNES Datalake server, which utilizes the S3 API (see CNES Data processing centre; CNES, 2024).

2.3 Libraries and formats

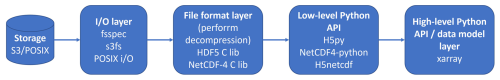

All Python libraries evaluated in this study for reading netCDF-4 files rely on the HDF5 C library for actual I/O operations and decompression. The Fig. 2 shows the software stack:

At the lowest level, the I/O layer depends on the storage backend, the HDF5 C library handles all I/O operations, chunk retrieval, and decompression. Built on top of HDF5, the netCDF-4 C library adds the netCDF data model, including dimensions, coordinate variables, and attribute conventions.

This study evaluates the following four python libraries to read datasets in the netCDF-4 format:

-

NetCDF4-python (Unidata, 2024): a Python interface to the netCDF-4 C library (version 1.7.2 used in our test), which itself depends on the HDF5 C library. It exposes the netCDF data model directly to Python while delegating all I/O and decompression tasks to the underlying C libraries;

-

H5py library (Collette, 2013): is a Python interface to the HDF5 library (version 3.12.1 used in our test) Since netCDF-4 files are valid HDF5 files, h5py can read them, although it does not automatically interpret netCDF conventions;

-

H5netcdf is a pure Python package that use h5py as its backend while adding netCDF aware functionality (dimension handling, attributes). It avoids the dependency on the NetCDF-4 C library;

-

Xarray library (Hoyer and Hamman, 2017) provides a high-level data model interface (including labelled arrays and datasets) and delegates I/O operations to backend engines such as h5netcdf or netcdf4-python. Xarray itself does not perform any I/O or decompression; it only interprets the data returned by its backends (version 2024.9.0 used in our test);

-

Chunkindex: our custom chunk-indexing package described in Sect. 3.

Additionally, the study compares the performance of netCDF-4 with other formats designed for the cloud, namely Zarr and ncZarr. NcZarr (Fisher and Heimbigner, 2020) is an extension of the Zarr version 2 specification that encapsulates the complete netCDF data model and provides a mechanism for storing netCDF data in Zarr storage.

Only one library is used to evaluate performances for each of these two formats:

-

Zarr-python (Miles et al., 2020) is a pure Python implementation that performs I/O through fsspec or similar filesystem abstractions, and uses separate codec libraries (e.g., numcodecs, blosc) for decompression. The performance evaluation conducted in Sect. 5 employs the Zarr library directly to access the datasets formatted in Zarr (version 2.18.3 used in our test).

-

ncZarr (Fisher and Heimbigner, 2020) is an extension of the Zarr version 2 specification that encapsulates the complete netCDF data model and provides a mechanism for storing netCDF data in Zarr storage. The performance evaluation presented in Sect. 5 uses the Zarr library to read files from the local filesystem. The ncZarr format is fully compatible with the Zarr library.

It should be noted that the HDF5 library also provides a Read-Only S3 (ROS3) virtual file driver, which enables direct access to HDF5/netCDF-4 files stored in S3-compatible object stores without requiring fsspec or s3fs. Although the ROS3 driver was not evaluated in this study, it represents a promising alternative for accessing netCDF-4 files on cloud storage.

The chunkindex package (Penard et al., 2025b) is designed to speed-up access to a dataset stored and archived remotely in compressed netCDF-4 format, without requiring changes to the data structure or format, and avoiding a complete archive reprocessing. It indexes the content of the compressed chunk, creating an index that can be used to navigate within the compressed chunks without decompressing the data. This allows transferring smaller parts of the chunks when requested by the user. The index creation requires reading and decompressing the data only once. It can then be utilized each time the data is accessed. The dataset's file format, structure, or content is not modified: the index is stored alongside the dataset, either locally or remotely. This is a key advantage for data producers: they do not need to reformat their data. On one hand, they can provide an index file to accelerate access to their datasets. On the other hand, users can create their own index that may contain different index points. Furthermore, users have the ability to expand existing index files, for example when accessing specific parts of the dataset for the first time.

Data providers can be tempted to restructure existing datasets to adapt the storage layout to better suit user's needs, i.e. to re-chunk the data (Nguyen et al., 2023). For instance, the storage layout in Earth observation satellite datasets is typically a temporal sequence of spatial frames, i.e. the storage layout is inherently linked to the way the data have been produced. However, several users access these datasets for temporal analysis of a small spatial location. This storage layout is thus far from being adapted to their use case. Both reformatting and re-chunking would necessitate processing significant volumes of data. As an alternative, the chunkindex package allows keeping the datasets in their original netCDF-4 format and layout by indexing the data stored in the chunks, creating so-called sub-chunks. Reading and downloading a sub-chunk is faster than reading and downloading a full chunk. Hence, sub-chunking helps providing a faster access for such temporal analysis.

The chunkindex package is implemented using zran interface in Python (Forrest, 2023 and McCarthy, 2018) to create the index and h5py library to navigate in the netCDF-4 datasets and to read and write the index files.

3.1 Sub-chunking approach

Large chunks hinder the efficiency of data transmission when the internet connection is weak. In boats, downloading chunks as small as 10 MB can even prove prohibitive. Yet, model data and numerical simulations are sometimes stored with large chunk sizes, optimized for use on supercomputers where ample amounts of RAM are available. For example, data produced by numerical models are sometimes saved as a whole when produced, creating large time-frame chunks. Other sources of data may have been created with only one chunk per variable.

Although kerchunk (Durant, 2021 and Sterzinger et al., 2021) has been created to provide direct access to full chunks, it also provides a sub-chunking functionality that can help mitigate the problem with large chunks. The sub-chunking divides a chunk into subsections. This functionality allows reading a portion of a chunk without loading the entire chunk. However, this feature only supports uncompressed chunks. Similarly, the partial_decompress option in the Zarr format (Miles et al., 2020) allows reading small parts of compressed chunks. However, this option is available only if the chunk is compressed using Blosc.

Yet, most netCDF-4 datasets utilize deflate compression (Deutsch, 1996). Therefore, the goal of the chunkindex package is to provide support for sub-chunking of data compressed with deflate.

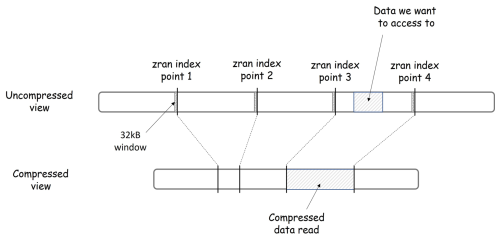

3.2 Principle of zran index

The chunkindex package indexes the content of compressed chunks using the zran tool available with the zlib library (Deutsch and Gailly, 1996), specifically the zran interface in Python (Forrest, 2023 and McCarthy, 2018). Zlib implements the functions for deflate compression and decompression. The zran tool allows the creation of index points at various positions in the compressed or uncompressed bit-stream. Each index point is associated with a window of 32 kB of uncompressed data. This is the maximum window size allowed in Zlib (Deutsch and Gailly, 1996). This data is the compression context. In zran, it is used to initialize the zlib decompression at any index point, as if the compressed data started from that point. Therefore, instead of decompressing the entire chunk from the beginning, the chunkindex package can pinpoint the desired starting index point and initiate the decompression from that location. The chunkindex package utilizes the information provided by the index points for navigating and seeking within the compressed file. It allows determining the location of specific sub-chunks without decompressing the data. Each index points is stored with the following data:

-

outloc: the location of the point in the uncompressed data;

-

inloc: the location of the point in the compressed data;

-

window: a 32 kB window of uncompressed data before the index point. It is the compression context required to initialize the state of the decompressor at this index.

If the dataset is stored on the local file system, the compressed sub-chunks are read moving the file position indicator at the beginning of the sub-chunk (inloc) and reading the data stream up to the next sub-chunk. If the dataset is stored on a remote server that accepts HTTP range request, a range request is sent to the server to read the byte-range corresponding to the sub-chunk.

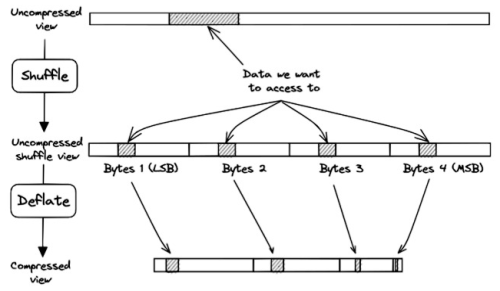

Figure 3 illustrates the principles of zran index points with two views of the same data: the uncompressed data view and the compressed data view. The chunk is depicted as a line segment. It is a sequence of bytes read from left to right. The line segment is shorter in the compressed view (bottom) than in the uncompressed view (top) to reflect a compression ratio greater than 1. Four index points are shown. They are evenly distributed in the uncompressed chunk but not in the compressed chunk due to deflate variable-length compression. A subset of data is represented as a hashed section in the uncompressed view. Its location is fully defined by an offset and a length. Thanks to the zran index points, it is not necessary to read and decompress the entire chunk to access this subset of data, but only the section that overlaps this subset between two index points. The chunkindex package identifies the locations of the previous and next index points. It fetches the corresponding location in the compressed version of the chunk, initializes the zlib library with the window associated with the previous index point, reads only the compressed data in the section between the two index points, and performs the decompression of the subset. In Fig. 3, the chunkindex identifies that the subset of data is located between index points 3 and 4. It reads and decompresses only the data in the section between those two index points, i.e. the section hashed in the compressed view and returns the subset of data.

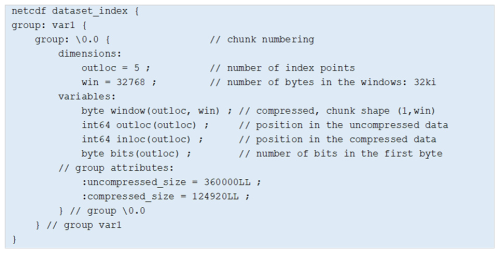

3.3 Index storage

The chunkindex package needs to decompress and scan the full chunk of data to be able to create the index. It may be created by the data provider and made available to users alongside the datasets. Chunkindex package uses the index to retrieve subsets of data in chunks. The index is composed of a list of index points, each containing a 32 kB window. The data volume of the index may be significant when there are too many index points. For instance, setting five index points in a chunk of 1 MB uncompressed, i.e. about one index point every 200 kB, results in an index of 160 kB or about 16 % the chunk data volume. Empirical tests show that a good compromise is to have three index points per chunk or a minimum of one index point every 2 MB of uncompressed data. This is the configuration applied in the performance evaluation in Sect. 5.

The index is stored in a netCDF-4 data structure to access the index points efficiently. The windows are compressed to reduce the index data volume. Figure 4 provides an example created for a hypothetical netCDF-4 dataset that contains a variable “var1” with one chunk numbered “0.0” to illustrate the index data structure. In this example, the index contains five points as indicated by the dimension outloc. The index windows are stored as a 2D variable window of dimensions (outloc, win) where win is the window size i.e. 32 kB. This variable is chunked with a shape (1, win) for an efficient access to the window associated with each index point. It is compressed with deflate to reduce the data volume of the windows. The outloc and inloc variables store the position of the index points, respectively, in the uncompressed and compressed versions of the data. The variable bits indicates how many bits of the first byte read in the compressed stream are utilized to start the decompression. Indeed, data samples do not occupy full bytes when compressed. Last, the uncompressed_size and compress_size attributes convey the size of the chunk in its uncompressed and compressed versions.

3.4 Sub-chunking with shuffling

The process for decompressing the data gets more complicated when shuffling is applied prior to the compression. Shuffling is a popular pre-compression step in netCDF-4 because it allows increasing both the compression speed and the compression ratio of most scientific datasets (Hartnett and Rew, 2008). Shuffling aims to exploit potential redundancies within the data structure and enhance the compressibility of the dataset by reordering data bytes by significance within the chunk. The problem for the chunkindex package is that shuffling disperses the bytes of samples throughout the chunk. Figure 5 illustrates this problem for samples with a data type of 4 bytes (e.g. int32, float32). A subset of data is represented hashed in the uncompressed segment (top). Shuffle scatters the continuous subset of data in the shuffled version of the chunk (middle) and therefore, scatters the data in the compressed chunk (bottom). Consequently, the chunkindex package needs to read and decompress at least four sections of the compressed chunk to be able to reconstruct the continuous subset. This clearly affects the performance of the chunkindex solution because it needs to retrieve more index points and read more compressed data to reconstruct the subset of data.

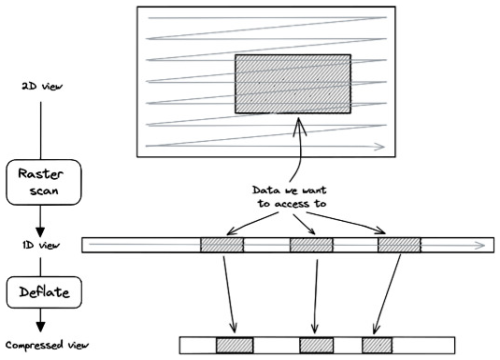

3.5 Sub-chunking in multi-dimensional datasets

A similar problem occurs when accessing a multi-dimensional subset in a multi-dimensional chunk stored in raster-scan order. Figure 6 illustrates this problem in the 2D case. The connected subset of data is scattered in the compressed chunk. The number of compressed data sections required to reconstruct the connected subset increases with the dimensions. Consequently, the chunkindex package needs to read and decompress more sections of the compressed chunk to reconstruct the connected subset, once again affecting the performance of the chunkindex. The performance is further affected when multi-dimensional datasets are compressed with shuffle.

3.6 Limitations

While the sub-chunking strategy offers significant performance benefits for specific access patterns, it also has certain limitations that users should be aware of:

-

Index synchronization. The external index file is tightly coupled to the contents of the compressed chunks in the original netCDF-4 file. If the original file is modified (e.g., appended to or rewritten), the index will become out of sync, potentially leading to corrupted data retrieval or decompression errors.

-

Request coalescence. Many cloud-optimized libraries (e.g., fsspec, s3fs) implement request coalescing, where multiple adjacent or nearby small read requests are merged into a single larger HTTP GET request to optimize throughput and reduce latency overhead. The current implementation of chunkindex issues individual range requests for each sub-chunk. While this minimizes data transfer volume, it may result in a higher number of HTTP requests compared to reading full chunks with coalescing, which could be suboptimal in high-latency network environments or when many adjacent sub-chunks are requested sequentially.

-

Index overhead. Creating the sub-chunk index requires reading and decompressing the entire dataset once, representing an initial computational cost. Additionally, the index files consume storage space. In our experiments, the index size was approximately 16 % of the original data volume. This overhead must be weighed against the expected savings in data transfer and access time.

3.7 Scope of Applicability

The chunkindex library currently supports the following features:

-

File Formats. The library supports standard netCDF-4 files and valid HDF5 files;

-

Compression. Support is currently limited to the deflate (zlib) compression algorithm, which is the standard for netCDF-4. All compression levels (1–9) are supported. Other compression algorithms (e.g., SZIP) or third-party filters (e.g., Blosc, Zstd, LZF) are not currently supported;

-

Shuffle. The HDF5 shuffle filter is supported. However, as discussed in Sect. 3.2, shuffling changes the byte alignment of the compressed data, which can reduce the precision of the sub-chunk index.

Generally, users access netCDF files using one of the following two patterns:

-

Read a time series for a small spatial region or,

-

Read a large spatial (2D or 3D) region (say, continental or global) at a specific time.

Very few access the dataset with a pattern between the two. Hence, these two patterns are considered in the experiments. The experiments read parts of the datasets described below to evaluate the performance of the libraries listed in Sect. 2 under various conditions. The dataset consists in two kinds of data:

-

One file from ocean model coming from Copernicus Monitoring Environment Marine Service (CMEMS, Clementi et al., 2021), with small chunk of less than 2 MB;

-

One file from the meteorological Global Forecast System (GFS) reformatted in a netCDF-4 file, with large chunk of about 50 MB (see NOAA, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administrationl; NOAA, 2024).

Some files have been modified to fit to our test conditions, for instance to change the shuffle filter. The original GFS file was in GRIB, it has been converted in netCDF-4. Deflate compression with level 4 is applied to all variables in these netCDF-4 files either with or without the shuffle filter activated. The parts of data read in each file are identified in the following subsections. The chunkindex package does not require any modification to original files, only an index file is created to store the index for each netCDF-4 file using the chunkindex package.

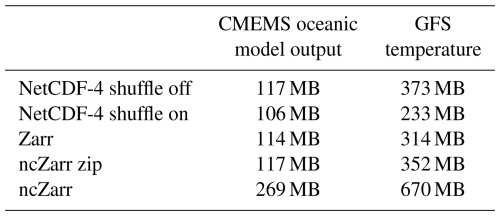

Zarr and ncZarr versions of this dataset are also generated from these netCDF-4 files with the same content and the same chunking structure. Within Zarr, the default compression method is activated: the meta-compression Blosc with LZ4 compressor at level 5 and shuffle activated. This choice reflects typical real-world usage, as most users rely on default settings when converting data to the Zarr format. However, it should be noted that LZ4 decompression is generally faster than deflate decompression, which may contribute to Zarr's performance advantage in some of our experiments. Using deflate compression within Blosc would have provided a more direct comparison with the deflate-compressed netCDF-4 files. We did not manage to activate the internal compression in ncZarr (problem in our version during the tests, probably fixed now). Hence, the ncZarr dataset is neither compressed nor shuffled. Table 1 below provides the file size in the different formats. In this table, the data volume of the ncZarr dataset is provided with external zip compression.

The dataset is more compact in the form of netCDF-4 with shuffle. However, deactivating the shuffle can speed-up the access time.

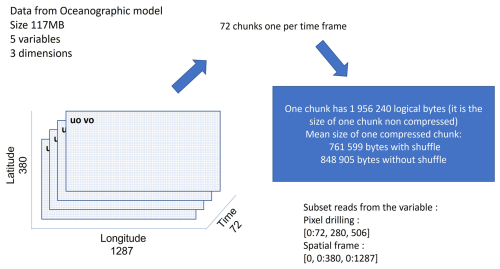

4.1 CMEMS oceanic model output

Figure 7 shows the structure of the files coming from the 3D oceanographic model output from Copernicus Monitoring Environment Marine Service (CMEMS). The variable uo is a 3D variable with one temporal dimension (time) and two spatial dimensions (lat, lon) with the dimension length of time: 72, lat: 380 and lon: 1287. It contains 72 chunks of 1.9 MB uncompressed. One chunk is a spatial frame of dimensions (lat, lon).

Two experiments are conducted on this dataset. The first consists in reading the time series for the pixel at the coordinates (lat = 280, lon = 506), i.e. the data across the entire temporal dimension but only for this pixel. This use case requires reading and uncompressing the 72 chunks. The second consists in reading the first spatial frame, i.e. the spatial frame at time = 0. This use case requires reading and uncompressing only the first chunk.

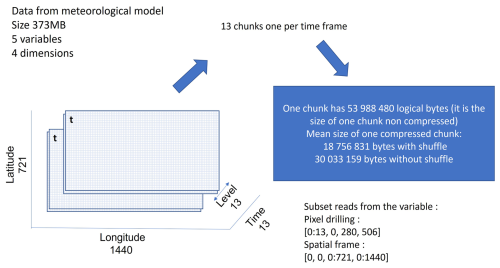

4.2 GFS meteorological model output

Figure 8 shows the structure of a file from the Data Weather Aggregation Service of Thales. It contains the air_temperature variable. This is a 4D variable with dimension lengths time: 13, isobaricInhPa: 13, latitude: 721, and longitude: 1440. It contains 13 chunks of 54 MB uncompressed. One chunk is a 3D frame of dimensions (isobaricInhPa, latitude, longitude).

Two experiments are also conducted on this dataset. The first consists in reading the time series for the pixel at the first pressure level (isobaricInhPa = 0) and at the coordinates (latitude = 280, longitude = 506). This use case requires reading and uncompressing the 13 chunks. The second consists in reading the first spatial frame at the first pressure level, i.e. the spatial frame at (time = 0, isobaricInhPa = 0). This use case requires reading and uncompressing the first chunk, but only the first part of the chunk is requested.

This section compares performance of the libraries listed in section 2.3 for:

-

Reading data from the local POSIX file system;

-

Reading data from a remote POSIX file system, simulating a poor network connection (limited speed and delay);

-

Reading data from a S3 storage service.

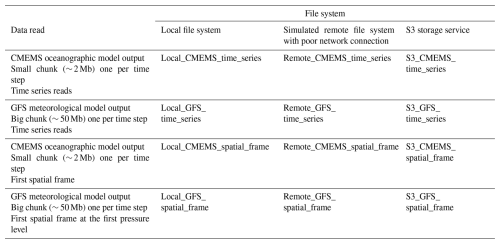

Table 2 recaps the experimental conditions in which the performances are evaluated. It provides a name to each experiment.

Only the reading time is measured. The Python library time is used to calculate the elapsed time during the calls to open the file, request data, and retrieve data from the file. This operation is repeated 10 times. No write tests are conducted during this experiment. A comparison between the data read and a reference dataset is performed using NumPy to verify the accuracy of the reading process.

Dask is not enabled: the reading process is done with one CPU.

The name is defined as: {file_system}_{product}_{access_type}

Where:

-

{file_system} can be local, remote or S3

-

{product} can be CMEMS or GFS

-

{access_type} can be time_series or spatial_frame.

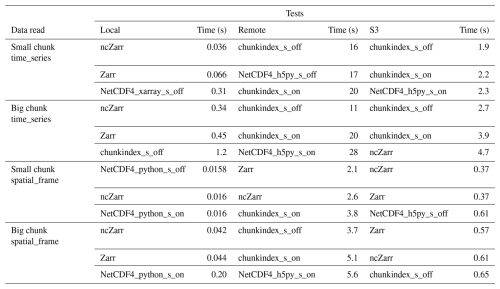

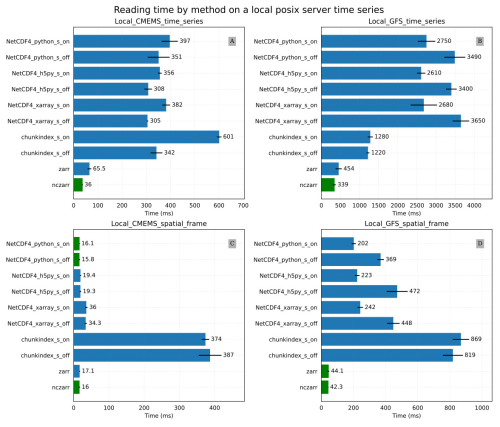

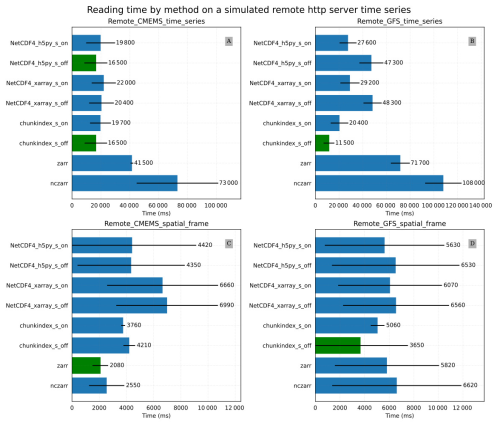

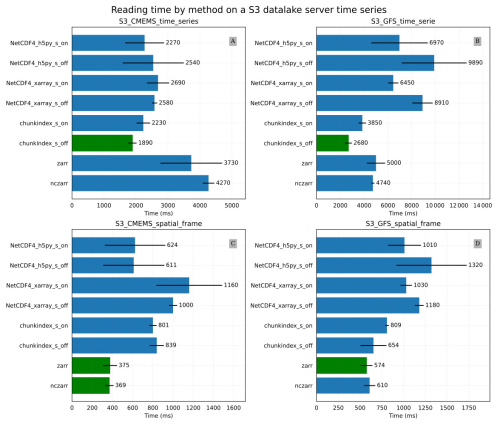

The results are provided in Figs. 9 to 11. These figures provide the mean time (bars) and the standard deviation (thin black lines) over 10 identical tests for reading the values described in the 18 experiments. In these figures, the python-netCDF4 library is identified as “NetCDF4_python” and the suffixes “s_on” and “s_off” indicate whether the shuffle is activated or not in the dataset.

5.1 Reading from the local file system

Figure 9A provides the results of the Local_CMEMS_time_series experiment that reads a time series of the variable “uo” of the CMEMS oceanic model output. All NetCDF libraries take approximately the same time to read the data, except for chunkindex, which is 2 times slower when the shuffle filter is activated in the dataset. The ncZarr and Zarr libraries are the fastest. In this CMEMS file, the compressed chunks are small enough to allow fast access to small parts of the data.

Figure 9Results of the local file system experiment: (A) the Local_CMEMS_time_series mean time for reading a time series in the CMEMS oceanic model output (B) the Local_GFS_time_series mean time for reading a time series in the GFS temperature dataset (C) the Local_CMEMS_spatial_frame mean time for reading a spatial frame in the CMEMS oceanic model output (D) the Local_GFS_spatial_frame mean time for reading a spatial frame in the GFS temperature dataset.

Figure 9B provides the results of the Local_GFS_time_series experiments for reading a time series of the variable “air_temperature” in the GFS temperature dataset. This variable contains big chunks of about 18 MB compressed. In this case, the libraries netcdf4-python, h5py and xarray take approximately the same time to read the time series. However, Zarr, ncZarr are almost 8 to 10 times faster. The difference in performance may be due to netCDF cache size (16 MB by default) that is smaller than the chunk size here. The chunkindex is particularly efficient here because it allows reading and decompressing a small part of the chunks.

Figure 9C and D provide results of the Local_CMEMS_spatial_frame and the Local_GFS_spatial_frame experiments respectively. In the Local_CMEMS_spatial_frame experiment, a full chunk is read. In the Local_GFS_spatial_frame experiment, only a small portion of the file is read. The chunkindex package is clearly the worst solution in both cases. The performance of the chunkindex package is penalized by the time required to read the index file. The performance of the other libraries is the same order of magnitude for Local_CMEMS_spatial_frame. Nevertheless, it may be noticed that Zarr and ncZarr are faster than the other libraries in the Local_GFS_spatial_frame. This is due to the same reason as the results of the Local_GFS_time_series experiment: the size of NetCDF chunk is large (about 18 MB).

It can be observed that reading a time series of only 72 values in the Local_CMEMS_time_series experiment takes more than 0.4 s (Fig. 9A), whereas reading a spatial frame of 489 060 values in Local_CMEMS_spatial_frame experiment (Fig. 9C) can take less than 0.02 s. This is due to the chunking structure of the dataset, which favour the performance for accessing spatial frames in this case: the access to a time series requires reading and decompressing all chunks of the dataset whereas the access to only one spatial frame requires reading and decompressing only one chunk. This example shows that the chunking structure has to be adapted to the most commonly utilized reading pattern by users.

5.2 Reading from a simulated remote file system with poor network connection

This section provides the results of the experiments conducted simulating a remote file system with poor network connection, i.e. with a bandwidth limited to 100 kB s−1 and a fixed delay of 100 ms. These conditions are simulated serving the dataset through a lighttpd server (lighttpd) and using the Linux command tc qdisc to limit the bandwidth and delay. The NetCDF, Zarr and ncZarr dataset is read using fsspec (Durant, 2018) via the URL provided by the lighttpd server. We encountered difficulties accessing the dataset through the netcdf4-python library, either directly via the URL or using fsspec. In fact, the netcdf4-python library requires a file path and does not support reading from in-memory buffers, limiting its compatibility with fsspec-based virtual file systems. Hence, no result is provided for the netcdf4-python library.

Figure 10Results of simulated remote file system with poor network connection: (A) the Remote_CMEMS_time_series experiment mean time for reading a time series in the CMEMS oceanic model (B) the Remote_GFS_time_series experiment mean time for reading a time series in the GFS temperature dataset (C) the Remote_CMEMS_spatial_frame experiment mean time for reading a spatial frame in the CMEMS oceanic model output (D) the Remote_GFS_spatial_frame experiment mean time for reading a spatial frame in the GFS temperature dataset.

Figure 10A and B provide the results of the Remote_CMEMS_time_series and Remote_GFS_time_series experiments respectively. In the Remote_CMEMS_time_series experiment, chunkindex performance is comparable to the performance of h5py. Chunkindex is faster in the Remote_GFS_time_series experiment in which the netCDF-4 file is created with big chunks. Zarr and ncZarr are slower in both cases.

Figure 10C and D provide the results of the Remote_CMEMS_spatial_frame and the Remote_GFS_spatial_frame experiments respectively. Zarr is the fastest format in the Remote_CMEMS_spatial_frame. The chunkindex format and package decreased the reading time in the Remote_GFS_spatial_frame experiment in which the netCDF-4 file was created with big chunks.

In the four experiments, the chunkindex package shows interesting performance, despite the time lost in reading the index file. With a poor quality network connection, reducing the number of requests and the size of packets can save time.

5.3 Results on S3

This section provides the results of the experiments conducted on an S3 file system. We do not manage accessing the dataset with the netcdf4-python library on our S3 server. At time of writing, this library does not support s3fs protocol nor fsspec. Hence, no result is provided for the netcdf4-python library.

Figure 11Results of the S3 storage service experiment: (A) S3_CMEMS_time_series mean time for reading a time series in the CMEMS oceanic model output (B) S3_GFS_time_serie mean time for reading a time series in the GFS temperature dataset (C) S3_CMEMS_spatial_frame mean time for reading a spatial frame in the CMEMS oceanic model output (D) S3_GFS_ spatial_frame mean time for reading a spatial frame in the GFS temperature dataset.

Figure 11A and B provide the results of the S3_CMEMS_time_series and S3_GFS_time_series experiments respectively. In these conditions, chunkindex is the fastest library in both cases. It decreases the reading time compared to the use of the other libraries, especially on the version of the dataset without the shuffle filter activated.

Figure 11C and D provide the results of the S3_CMEMS_spatial_frame and the S3_GFS_spatial_frame experiments respectively. The fastest libraries in the both experiments are ncZarr and Zarr.

5.4 Summary

Table 3 summarizes the results identifying the three fastest formats and libraries in the various conditions of the experiments.

For accessing netCDF-4 datasets in the local file system, NetCDF4-python and h5py are usually the best choice.

For reading time series from datasets with very large chunks (GFS experiments), chunkindex, ncZarr and Zarr have better performance. For accessing remote datasets when the network connection is degraded, chunkindex is usually the best choice, especially when the shuffle filter has not been activated and on file with large chunks.

For spatial frames experiments, Zarr and ncZarr libraries provide better results. Nevertheless, NetCDF4-python shows good performance on CMEMS files, the lower performance on GFS files is mainly due to the chunk size, which penalizes NetCDF reading performance.

As expected, chunkindex performs well in the use cases where small amounts of data need to be retrieved in large compressed chunks. Moreover, it can significantly increase the performance for reading remote dataset created without the shuffle filter activated. Yet, most of the netCDF-4 datasets already existing and archived have the shuffle filter activated. The performance gap offered by the chunkindex package may not be large enough for a wide adoption. Nevertheless, this software library is still in the early phases of its development. There may be room for optimisation to increase its performances and to facilitate its usability.

For the remote and S3 experiments, netCDF-4 and ncZarr datasets were accessed using fsspec (version 2024.9.0) with default configuration settings. The default block size for fsspec is 5 MB, meaning data is read in 5 MB increments regardless of the actual amount requested. This can lead to over-fetching (reading more data than needed) or multiple sequential requests when accessing data spanning multiple blocks, both of which contribute to increased runtime.

Fsspec offers several caching strategies (e.g., read-ahead caching, block caching, whole-file caching) that can significantly impact performance. Readers should note that the results presented here are specific to the default fsspec configuration, and optimal settings may vary depending on the use case, access pattern, and network conditions.

It is important to acknowledge that the results presented here explore only a small portion of the possible parameter space for reading netCDF-4 data over the network. The performance of I/O operations in cloud environments is influenced by numerous factors, including software versions, configuration settings (e.g., fsspec caching strategies, concurrency limits, NetCDF caching strategies), network conditions, and server-side configurations. Similarly, newer versions of libraries like Zarr-python may exhibit significantly different performance characteristics compared to the versions tested here. While our benchmarks provide a valuable snapshot of performance for common configurations, readers should consider these variables when extrapolating results to other contexts.

This study compares the performances of four Python libraries netcdf4-python, xarray, h5py, and a custom chunk-indexing library for accessing a netCDF-4 dataset as well as the performance Zarr and ncZarr data formats. It also shows the impact of different data structures (chunk size and chunk layout) and data access (time series or spatial frame) on reading time. The test datasets utilized are composed of two files from meteorological and ocean numerical models.

Results show that the NetCDF4-python and h5py libraries are the fastest for reading netCDF-4 files in a local POSIX file system. At the time of writing this article, these libraries may be preferred over the xarray library for performance-critical code.

The Zarr format appears to be performant for accessing datasets both on S3 file system and on POSIX file system. Yet the performance of accessing netCDF-4 datasets remotely via h5py and s3fs on S3 is the same order of magnitude. In our opinion, converting netCDF-4 datasets to the Zarr format when moving to cloud is not justified. Indeed, the netCDF-4 format is used in many applications and benefits from a large ecosystem of tools. Moreover, netCDF-4 files may be easier to manipulate (copied, moved, removed, etc…) than Zarr datasets composed of multiple small files and directories (one by chunk per file and one directory per variable). The small gain in performance does not justify the efforts required to adapt the application source code and the cost of converting the datasets to a new format. On the contrary, with a good chunk size and distribution netCDF-4 shows good performance on S3. Moreover, recent versions of HDF5 library are more efficient with object storage. One file is no longer associated with only one key. A NetCDF file, for instance, is split into several key/value pair in object storage.

The ncZarr approach is also interesting. It tries to keep the netCDF-4 interface while modifying the storage layer hidden to the users. Doing so, it combines the advantages of both the netCDF-4 and Zarr formats. The ncZarr format could be a good compromise between performance and portability while using cloud object storage. However, it is still young and needs some improvements to become the perfect solution.

The chunkindex package could also be a good solution to improve the access time to files created with big chunks over the spatial dimension. This is typically the case of files produced by oceanographic or atmospheric models. These models write the results at a regular time step, producing chunks per time frame. The chunkindex package excels in reading small data parts in big chunks. It can thus help reducing the amount of data to download, speeding up the data transfer under degraded network conditions. This proves especially useful for accessing time series, i.e. the worst access pattern for this chunking layout.

Finding the right shapes and sizes for chunks is a challenging task. There isn't a definitive answer to this, as it always involves making compromises, various reading purposes requiring different strategies for chunking.

It is important to emphasize that sub-chunking is primarily designed as a practical solution for accessing existing archived datasets without the need for costly reformatting or re-chunking. In scenarios where the access pattern is known in advance and consistent, optimal re-chunking of the data (e.g., aligning chunks with time series for temporal analysis) will always yield better performance than sub-chunking.

However, for large archives already stored with suboptimal chunking strategies (such as large spatial chunks for time-series access), sub-chunking offers a significant performance improvement over reading full chunks, while avoiding the prohibitive costs of duplicating and restructuring petabytes of historical data.

To facilitate adoption, future development will aim to integrate chunkindex into Kerchunk or VirtualiZarr, providing an unified solution for optimized cloud access to legacy archives. We will also take a look at Icechunk, a recently developed alternative.

A future evolution of the library that could optimize performance may be a hybrid approach that automatically selects between sub-chunking and full-chunk access based on the request and chunk size.

The current chunkindex implementation relies on synchronous I/O operations provided by h5py. Adopting a fully asynchronous approach, compatible with the Zarr V3 specification, could deliver significant performance gains, especially for parallel and concurrent access patterns in high-latency cloud environments.

Future studies may evaluate the performances of NetCDF, Zarr and ncZarr formats in high parallel computing environments and with cloud-based datasets. This evaluation would assist in determining the most suitable format for accessing and processing data under these specific conditions.

The code is available under Apache-2.0 license at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15837583 (Penard et al., 2025b). It is also available on Github: https://github.com/CNES/netCDFchunkindex (last access: September 2025).

The datasets are available under Apache-2.0 license here https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15791345 (Penard et al., 2025a).

CP and XD developed the code, performed the tests and wrote the manuscript. CP, XD, FG and SH analyzed the results. FG and SH reviewed the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This work was funded by CNES and carried out at Thales Services Numeriques. We would like to thank Aimee Barciauska, Tina Odaka and Anne Fouilloux for their contributions, this helped us improving the quality of this paper.

This research has been supported by the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES).

This paper was edited by Sylwester Arabas and reviewed by Aleksandar Jelenak and Max Jones.

Ambatipudi, S. and Byna, S.: A comparison of HDF5, Zarr, and netCDF4 in performing common I/O operations, arXiv [preprint], https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2207.09503, 2022.

Barciauskas, A., Mandel, A., Barron, K., and Deziel, Z.: Cloud-Optimized Geospatial Formats Guide (cloudnativegeo.org) https://web.archive.org/web/20250413102259/https://guide.cloudnativegeo.org/ (last access: April 2025), 2023.

Carval, T., Bodere, E., Meillon, J., Woillez, M., Le Roux, J. F., Magin, J., and Odaka, T.: Enabling simple access to a data lake both from HPC and Cloud using Kerchunk and Intake, EGU General Assembly 2023, Vienna, Austria, 23–28 Apr 2023, EGU23-17494, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu23-17494, 2023.

Clementi, E., Aydogdu, A., Goglio, A. C., Pistoia, J., Escudier, R., Drudi, M., Grandi, A., Mariani, A., Lyubartsev, V., Lecci, R., Cretí, S., Coppini, G., Masina, S., and Pinardi, N.: Mediterranean Sea Physical Analysis and Forecast (CMEMS MED-Currents, EAS6 system) (Version 1), Copernicus Monitoring Environment Marine Service (CMEMS) [data set], https://doi.org/10.25423/CMCC/MEDSEA_ANALYSISFORECAST_PHY_006_013_EAS8, 2021.

CNES: Data processing centre of the french space agency CNES, https://web.archive.org/web/20241206205004/https://cnes.fr/en/projects/centre-de-calcul, last access: December 2024.

Collette, A.: Python and HDF5, Book, O'Reilly, ISBN 9781449367831, 2013.

Cornillon, P., Gallagher, J., and Sgouros, T.: OPeNDAP: Accessing data in a distributed, heterogeneous environment, Data Science Journal, 2, 164–174, https://doi.org/10.2481/dsj.2.164, 2003.

Deutsch, P.: DEFLATE compressed data format specification version 1.3 (No. rfc1951), https://doi.org/10.17487/RFC1951, 1996.

Deutsch, P. and Gailly, J. L.: Zlib compressed data format specification version 3.3 (No. rfc1950), https://doi.org/10.17487/RFC1950, 1996.

Durant, M.: fsspec: Filesystem interfaces for Python, https://web.archive.org/web/20250630141731/https://filesystem-spec.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (last access: October 2024), 2018.

Durant, M.: kerchunk library: Cloud-friendly access to archival data, https://web.archive.org/web/20260104023618/https://github.com/fsspec/kerchunk (last access: December 2025), 2021.

Durbin, C., Quinn, P., and Shum, D.: Task 51-cloud-optimized format study (No. GSFC-E-DAA-TN77973), https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20200001178 (last access: September 2025), 2020.

Fisher, W. and Heimbigner, D.: NetCDF in the Cloud: modernizing storage options for the netCDF Data Model with Zarr, EGU General Assembly 2020, Online, 4–8 May 2020, EGU2020-10341, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu2020-10341, 2020

Forrest, W.: Zran, Enabling random read access for deflate-compressed files http://web.archive.org/web/20230419192126/https://github.com/forrestfwilliams/zran (last access: April 2025), 2023.

Gallagher, J., Habermann, T., Jelenak, A., Lee, J., Potter, N., and Yang, M.: Task 28: Web Accessible APIs in the Cloud Trade Study (No. GSFC-E-DAA-TN46276), https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20170009584 (last access: September 2025), 2017.

Hartnett, E. and Rew, R. K.: Experience with an enhanced NetCDF data model and interface for scientific data access, in: 24th Conference on IIPS, http://web.archive.org/web/20250425012746/https://ams.confex.com/ams/88Annual/webprogram/Paper135122.html (last access: September 2025), 2008.

Hoyer, S. and Hamman, J.: xarray: N-D labeled Arrays and Datasets in Python. Journal of Open Research Software, 5, p. 10, https://doi.org/10.5334/jors.148, 2017.

Jelenak, A. and Robinson, D.: Strategies and Software to Optimize HDF5/netCDF-4 Files in the Cloud, in: AGU23, San Fransisco, 11–15, https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20230016687, 2023.

Lee, C., Yang, M., and Aydt, R.: NetCDF-4 performance report, http://web.archive.org/web/20250721214713/https://docs.hdfgroup.org/archive/support/pubs/papers/2008-06_netcdf4_perf_report.pdf (last access: April 2025), 2008.

lighttpd project: https://web.archive.org/web/20250728235313/https://www.lighttpd.net/ (last access: October 2024).

Lopez, L. A.: HDF5 at the Speed of Zarr, Pangeo Showcase, Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10830528, 2024.

Lopez, L. A., Barrett, P. A., Steiker, A., Jelenak, A., Kaser, L., and Lee, E. J.: Evaluating Cloud-Optimized HDF5 for NASA's ICESat-2 Mission, http://web.archive.org/web/20250326204329/https://nsidc.github.io/cloud-optimized-icesat2/ (last access: April 2025), 2025.

Marin, M., Brandson, P., and Mortimer, M.: A collection of intake catalogs and drivers to access AODN data directly in AWS S3, http://web.archive.org/web/20250721215610/https://github.com/IOMRC/intake-aodn (last access: April 2025), 2022.

McCarthy, P.: indexed_gzip Fast random access of gzip files in Python, https://web.archive.org/web/20251106114226/https://github.com/pauldmccarthy/indexed_gzip (last access: December 2025), 2018.

Miles, A., John Kirkham, J., Durant, M., Bourbeau, J., Onalan, T., Hamman, J., Patel, Z., Shikharsg, Rocklin, M., Dussin, R., Schut, V., Sales de Andrade, E., Abernathey, R., Noyes, C., Balmer, S., Tran, T., Saalfeld, S., Swaney, J., Moore, J., Jevnik, J., Kelleher, J., Funke, J., Sakkis, G., Barnes, C., and Banihirwe, A.: Zarr-developers/Zarr-python: V2.4.0, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3773450, 2020.

Nguyen, D. M. T., Cortes, J. C., Dunn, M. M., and Shiklomanov, A. N.: Impact of Chunk Size on Read Performance of Zarr Data in Cloud-based Object Stores, ESS Open Archive [preprint], https://doi.org/10.1002/essoar.10511054.2, 2023.

NOAA: Global Forecast System (GFS), http://web.archive.org/web/20240826064120/https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/weather-climate-models/global-forecast, last access: August 2024.

Penard, C., Gouillon, F., Delaunay, X., and Herlédan, S.: A new sub-chunking strategy for fast netCDF-4 access in local, remote and cloud infrastructures, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15791345, 2025a.

Penard, C., Gouillon, F., Delaunay, X., and Herlédan, S.: A new sub-chunking strategy for fast netCDF-4 access in local, remote and cloud infrastructures, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15837583, 2025b.

Pfander, I., Johnson, H., and Arms, S.: Comparing read times of Zarr, HDF5 and netCDF data formats, in: AGU fall meeting abstracts, 2021, IN15A-08, 2021.

POSIX certification: http://web.archive.org/web/20250426100004/https://posix.opengroup.org/, last access: December 2024.

Sterzinger, L., Durant, M., Signell, R., Gentemann, C., Paul, K., and Kent, J.: Cloud-performant reading of NetCDF4/HDF5/Grib2 using the Zarr library, in: AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, 2021, U51B-19, 2021.

SWOT mission: Surface Water and Ocean Topography, http://web.archive.org/web/20240910071057/https://cnes.fr/projets/swot, last access: December 2024.

Unidata: NetCDF 4 python interface, https://web.archive.org/web/20250729095049/https://github.com/Unidata/netcdf4-python, last access: October 2024.