the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The roles of volatile organic compound deposition and oxidation mechanisms in determining secondary organic aerosol production: a global perspective using the UKCA chemistry–climate model (vn8.4)

Jamie M. Kelly

Ruth M. Doherty

Fiona M. O'Connor

Graham W. Mann

Dantong Liu

The representation of volatile organic compound (VOC) deposition and oxidation mechanisms in the context of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation are developed in the United Kingdom Chemistry and Aerosol (UKCA) chemistry–climate model. Impacts of these developments on both the global SOA budget and model agreement with observations are quantified. Firstly, global model simulations were performed with varying VOC dry deposition and wet deposition fluxes. Including VOC dry deposition reduces the global annual-total SOA production rate by 2 %–32 %, with the range reflecting uncertainties in surface resistances. Including VOC wet deposition reduces the global annual-total SOA production rate by 15 % and is relatively insensitive to changes in effective Henry's law coefficients. Without precursor deposition, simulated SOA concentrations are lower than observed with a normalised mean bias (NMB) of −51 %. Hence, including SOA precursor deposition worsens model agreement with observations even further (NMB %). Secondly, for the anthropogenic and biomass burning VOC precursors of SOA (VOCANT∕BB), model simulations were performed by (a) varying the parent hydrocarbon reactivity, (b) varying the number of reaction intermediates, and (c) accounting for differences in volatility between oxidation products from various pathways. These changes were compared to a scheme where VOCANT∕BB adopts the reactivity of a monoterpene (α-pinene), and is oxidised in a single-step mechanism with a fixed SOA yield. By using the chemical reactivity of either benzene, toluene, or naphthalene for VOCANT∕BB, the global annual-total VOCANT∕BB oxidation rate changes by −3 %, −31 %, or −66 %, respectively, compared to when using α-pinene. Increasing the number of reaction intermediates, by introducing a peroxy radical (RO2), slightly slows the rate of SOA formation, but has no impact on the global annual-total SOA production rate. However, RO2 undergoes competitive oxidation reactions, forming products with substantially different volatilities. Accounting for the differences in product volatility between RO2 oxidation pathways increases the global SOA production rate by 153 % compared to using a single SOA yield. Overall, for relatively reactive compounds such as toluene and naphthalene, the reduction in reactivity for VOCANT∕BB oxidation is outweighed by accounting for the difference in volatility of RO2 products, leading to a net increase in the global annual-total SOA production rate of 85 % and 145 %, respectively, and improvements in model agreement (NMB of −46 % and 56 %, respectively). However, for benzene, the reduction in VOCANT∕BB oxidation is not outweighed by accounting for the difference in SOA yield pathways, leading to a small change in the global annual-total SOA production rate of −3 %, and a slight worsening of model agreement with observations (NMB %). These results highlight that variations in both VOC deposition and oxidation mechanisms contribute to substantial uncertainties in the global SOA budget and model agreement with observations.

- Article

(8521 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Aerosols are detrimental to human health (WHO, 2013) and are linked to climate change (Forster and Ramaswamy, 2007). The development of air quality and climate management plans are hindered by the challenges in representing aerosol within models. Secondary organic aerosol (SOA) is formed in the atmosphere from a variety of hydrocarbons. Gas-phase production of SOA occurs by condensation of volatile organic compound (VOC) oxidation products (Odum et al., 1996, 1997) and from semi-volatile and intermediate-volatility organic compounds (S/IVOCs) (Donahue et al., 2006, 2011). Additionally, SOA formation can take place within the aqueous phase of cloud and aerosol liquid water (McNeill, 2015; Ervens, 2015). The treatment of hydrocarbon physicochemical processes within SOA schemes varies sizably across global chemistry–climate and chemical transport models, and this is reflected in both an uncertain global SOA budget and poor model agreement with observations (Tsigaridis et al., 2014).

The diversity in model treatment of SOA formation is partially due to the myriad of unique organic molecules in the atmosphere, a small fraction of which have been measured (Goldstein and Galbally, 2007). In the simplest of schemes, production of SOA is calculated as a function of emissions, hence SOA is “emitted” as opposed to being formed in the atmosphere (Tsigaridis et al., 2014). In cases where gas-phase oxidation of SOA precursors is treated, several simplifications are commonly made. For example, biogenic VOCs, such as isoprene and monoterpenes, are known to have multi-generational oxidation mechanisms, but the mechanisms are often reduced to less than two reaction steps when implemented in global models (Chung and Seinfeld, 2002; Heald et al., 2011; Scott et al., 2014, 2015). Similarly, multi-generational oxidation mechanisms of aromatic compounds are often represented by less than two reaction steps (Tsigaridis and Kanakidou, 2003; Heald et al., 2011). Gas-phase oxidation schemes can also be simplified by grouping organic compounds together (i.e. “lumping”). In some schemes, organic compounds are lumped according to emissions types, anthropogenic or biomass burning (Spracklen et al., 2011; Hodzic et al., 2016), whereas in others they are grouped according to volatility (Donahue et al., 2006, 2011). By lumping organic species together, chemical ageing can be accounted for, even if the exact mechanism is not known. However, in grouping species together, molecular information is lost and therefore it is challenging to select the appropriate reaction coefficients and SOA yields from laboratory studies (Kelly et al., 2018). In more complex SOA schemes, gas-phase oxidation is treated explicitly (Lin et al., 2012, 2014;Khan et al., 2017), but this method is limited to SOA precursors with relatively well-known oxidation mechanisms.

The sources and physicochemical processes of hydrocarbons included within SOA schemes also vary between models. Examples of model diversity include the inclusion of SOA formation within the aqueous phase (Lin et al., 2014) and from S/IVOCs (Pye and Seinfeld, 2010), as well as SOA being treated as semi-volatile as opposed to non-volatile (Shrivastava et al., 2015). The treatment of dry (Bessagnet et al., 2010) and wet deposition (Knote et al., 2015) of SOA precursors is an another aspect of SOA which varies from model to model. Recent field and modelling studies have provided evidence that several known SOA precursors are susceptible to deposition. For example, explicit modelling of the oxidation of terpene and aromatic VOCs has identified extremely soluble products, with effective Henry's constants (Heff) ranging from 105 to 109 M atm−1 (Hodzic et al., 2014). This suggests efficient wet removal of SOA precursors, considering Heff for nitric acid (HNO3) is (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006). However, the molecule-specific deposition parameters determined in field studies (Nguyen et al., 2015) can be difficult to apply to the lumped compounds used in global SOA schemes. On a global scale, some modelling studies have indicated a sensitivity of SOA to variations in precursor deposition (Henze and Seinfeld, 2006; Pye and Seinfeld, 2010; Hodzic et al., 2016). A few global modelling studies include both dry and wet deposition of SOA precursors, but the deposition parameters used vary by several orders of magnitude. For example, Shrivastava et al. (2015) use a value for Heff of 7×103 M atm−1, whereas other studies use values ranging from 1×105 to 5.3×109 M atm−1 (Knote et al., 2015; Hodzic et al., 2016). In relation to dry deposition, field studies over forested regions of the USA have observed significant dry deposition of highly oxygenated VOCs (Nguyen et al., 2015). The most rigorous studies on dry deposition have only been conducted using regional-scale models. They found that dry removal of SOA precursors reduces modelled July-mean surface SOA concentrations by 20 %–40 % over Europe (Bessagnet et al., 2010), and reduces annual-average surface SOA concentrations by 46 % over the USA (Knote et al., 2015). Wet removal of SOA precursors reduces simulated annual-average surface SOA concentrations by 10 % over the USA, which reduces simulated positive biases in summertime SOA (Knote et al., 2015). However, previous studies have found that observed SOA concentrations in mid-latitude emission source regions tend to be lower compared to SOA concentrations simulated without the inclusion of VOC deposition (Kelly et al., 2018), but noted that elsewhere the lack of measurements precluded robust conclusions.

Vegetation is estimated to release around 1000 Tg (C) of VOCs into the atmosphere annually (Guenther et al., 2006, 2012). Estimates of the global annual-total SOA production rate from biogenic VOCs range from 27.6 to 97.5 Tg (SOA) a−1, which represents 54 % to 95 % of production from all sources (Farina et al., 2010; Hodzic et al., 2016). However, other emissions, such as fossil fuel and biofuel combustion as well as savannah and forest fires, may also be important sources of SOA. In urban environments, aromatic compounds, which are typically emitted from anthropogenic and biomass burning activities, account for 20 % to 30 % of total VOC emissions (Calvert et al., 2002). Therefore, in some cities such as Beijing (Guo et al., 2012), Shanghai (Peng et al., 2013), Guangzhou (Ding et al., 2012), and Jerusalem (Von Schneidemesser et al., 2010), SOA is primarily composed of aromatic compounds, as opposed to biogenic species. One observationally constrained global modelling study estimates an anthropogenically controlled global annual-total SOA production rate of 100 Tg (SOA) a−1, representing ∼70 % of production from all sources (Spracklen et al., 2011). In other regions, SOA can be dominated by biomass burning sources (Tiitta et al., 2014). The extrapolation of observations from aircraft campaigns (Cubison et al., 2011) and environmental chamber experiments (Bruns et al., 2016) suggests a global annual-total SOA production rate from biomass burning of 8 and 43 Tg (SOA) a−1, respectively. Furthermore, one global-scale modelling study predicts a global annual-total SOA production rate of 44 to 95 Tg (SOA) a−1 from biomass burning S/IVOCs (Shrivastava et al., 2015). Therefore, the dominant sources of SOA remain largely unknown.

The first studies to quantify the SOA yields from aromatic compounds (Odum et al., 1997, 1996) provide yields that are not high enough to account for the concentrations of aromatic SOA observed in field studies (Tsigaridis and Kanakidou, 2003; Hoyle et al., 2007). For instance, early estimates of SOA yields from aromatic compounds, which were conducted in relatively high nitrogen oxide (NOx = NO and NO2) concentrations, range between 5 % and 10 % (Odum et al., 1997, 1996). Consequently, the use of low SOA yields for aromatic compounds in global models results in low global annual-total SOA production rates ranging from just 0.05 to 2.5 Tg (SOA) a−1, which are negligible in comparison to biogenic sources (Tsigaridis and Kanakidou, 2003; Hoyle et al., 2007). However, more recent chamber studies suggest the SOA yields from aromatic compounds are strongly influenced by NOx concentrations (Hurley et al., 2001; Song et al., 2005; Ng et al., 2007; Chan et al., 2009). For example, in agreement with early estimates (Odum et al., 1996, 1997), Ng et al. (2007) also observed an SOA yield from aromatic VOCs of 5 %–10 % under high-NOx conditions. However, under lower NOx concentrations, Ng et al. (2007) measured substantially higher SOA yields of 37 %, 30 %, and 36 % for benzene (C6H6), toluene (C7H8), and xylene (C8H10), respectively. Similarly, under low-NOx conditions, Chan et al. (2009) observed an SOA yield of 73 % from naphthalene (C10H8). Zhang et al. (2014) further corroborates this negative sensitivity of SOA yields from aromatic compounds to NOx concentrations and also highlights how chamber studies frequently underestimate SOA yields due to wall losses.

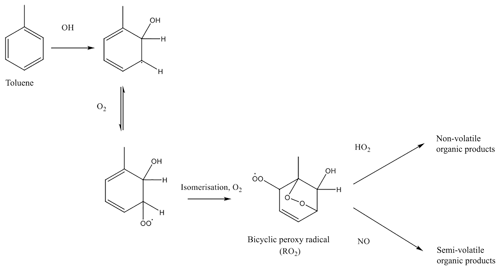

The exact mechanism describing aromatic oxidation is not yet fully understood, despite considerable progress to date (Kautzman et al., 2010; Li et al., 2016, 2017b; Al-Naiema and Stone, 2017; Schwantes et al., 2017). As aromatic oxidation is initiated by the hydroxyl radical (OH), the influence of NOx on SOA production is probably due to reaction of NO with subsequent reaction intermediates or products. Oxidation of the parent aromatic hydrocarbon by OH is followed by addition of molecular oxygen (O2) and isomerisation, forming a bicyclic peroxy radical, RO2 (Koch et al., 2007; Birdsall et al., 2010). Under high-NOx conditions, the peroxy radical reacts with the nitric oxide radical (NO) to form fragmented products, whereas under low-NOx conditions the peroxy radical reacts with the hydroperoxyl radical (HO2) to form functionalised products (Ng et al., 2007). Hence, due to the difference in volatility of products, the RO2+HO2 yields a greater mass of SOA compared to the RO2+NO pathway. Water vapour may also be involved in the gas-phase oxidation of aromatic compounds (Hinks et al., 2018). However, as both positive (White et al., 2014) and negative (Cocker et al., 2001) correlations between aromatic SOA yields and relative humidity have been observed in chamber studies, the role of water vapour in aromatic oxidation is not yet clear. The exact mechanism describing aromatic oxidation may not be fully understood but the observed influence of NOx on SOA yields suggests that simulating SOA production from aromatic compounds necessitates multi-generational oxidation mechanisms, with SOA yields responding to oxidant availability.

The peroxy radical reaction intermediate, together with competitive NO and HO2 reactions with varying SOA yields, has been applied to several different SOA schemes. Benzene, toluene, and xylene have been incorporated into both global- (Henze et al., 2008; Heald et al., 2011) and regional-scale models (Li et al., 2017a). Henze et al. (2008) applied the laboratory-derived yields from Ng et al. (2007) to aromatic compounds (16 Tg (VOC) a−1), which resulted in a global annual-total SOA production rate of 4 Tg (SOA) a−1, with 61 % of SOA being produced via the RO2+HO2 pathway. Peroxy radical chemistry has also been applied to IVOCs, which are a mixture of species emitted from both anthropogenic and biomass burning. Pye and Seinfeld (2010) applied the laboratory-derived yields from Chan et al. (2009) to IVOCs (18 Tg (VOC) a−1), which resulted in global annual-total SOA production rate of 5 Tg (SOA) a−1, with 75 % of SOA being produced via the RO2+HO2 pathway. Despite peroxy radical chemistry being included in some SOA schemes, the influence on the global SOA budget and model agreement with observations has not been quantified.

The objective of this study is to further develop the SOA scheme within a chemistry–climate model, the United Kingdom Chemistry and Aerosol (UKCA) model. Firstly, the model is updated to include the wet and dry deposition of SOA precursors. Secondly, the mechanism describing SOA formation from anthropogenic and biomass burning VOCs is updated to account for the influence of NOx on SOA yields. Several simulations are conducted to test the sensitivity of SOA to both precursor deposition and oxidation mechanisms. The impact of these model developments on SOA is assessed through a comprehensive comparison with available observations. The paper is organised as follows. The global chemistry–climate model used in this study is described in Sect. 2; this section also includes a description of the model developments applied to the SOA scheme. Observations used to evaluate the model are discussed in Sect. 3. Next, the influence of precursor deposition on SOA is investigated (Sect. 4). In Sect. 5, the sensitivity of modelled SOA to oxidation mechanisms and VOC reactivity is explored. Concluding remarks and further work are discussed in Sect. 6.

In this section, the model is briefly described. This begins with a brief description of the default configuration, followed by the model developments made in this study. The chemistry–climate model used in this study is the United Kingdom Chemistry and Aerosol (UKCA) model (Morgenstern et al., 2009; Mann et al., 2010; O'Connor et al., 2014) which is coupled to the Global Atmosphere 4.0 (GA4.0) configuration (Walters et al., 2014) of the Hadley Centre Global Environmental Model (Hewitt et al., 2011) version 3 (HadGEM3). The atmosphere-only configuration with prescribed sea surface temperature and sea ice fields based on 1995–2004 reanalyses data (Reynolds et al., 2007) was used. The model was run at a horizontal resolution of N96 (1.875∘ longitude by 1.25∘ latitude) with 85 terrain-following hybrid-height levels distributed from the surface to 85 km. Horizontal winds and temperature in the model were nudged towards ERA-Interim reanalyses for the 1999–2000 period (Dee et al., 2011) using a Newtonian relaxation technique with a relaxation time constant of 6 h (Telford et al., 2008). There was no feedback from the chemistry or aerosols onto the dynamics of the model; this ensured identical meteorology across all simulations so that differences in SOA were solely due to differences in precursor oxidation mechanisms and deposition.

2.1 Gaseous chemistry (UKCA)

The United Kingdom Chemistry and Aerosol (UKCA) model used in this study combines the “TropIsop” tropospheric chemistry scheme from O'Connor et al. (2014) with the stratospheric chemistry scheme from Morgenstern et al. (2009). There are 75 species with 285 reactions. This includes odd oxygen (Ox), nitrogen (NOy), hydrogen (HOx = OH+HO2), and carbon monoxide (CO). Explicit hydrocarbons included are methane, ethane, propane, isoprene, and monoterpene. Isoprene oxidation follows the Mainz Isoprene Mechanism (Pöschl et al., 2000) which is described in detail in O'Connor et al. (2014). In addition to the aforementioned explicit hydrocarbons, two additional non-explicit VOCs are included: VOCANT and VOCBB are lumped compounds representing anthropogenic and biomass burning VOCs, respectively. Together, isoprene, monoterpene, VOCANT, and VOCBB are the precursors of SOA. The reactivity and production of SOA from these species are discussed in further detail in Sect. 2.5. For bimolecular gas-phase reactions, rate constants are calculated following the Arrhenius expression

where k0 is a constant, β is the ratio of the activation energy over the universal gas constant (EA∕R), and T is temperature. The rate constant is then used to calculate the rate of reaction:

where k is the rate coefficient, and [A] and [B] are concentrations of gases A and B, respectively.

2.1.1 Gaseous wet deposition

Within UKCA, wet deposition of gases is calculated as a first-order process as a function of precipitation, following Walton et al. (1988). For a detailed description of the wet deposition within UKCA, see O'Connor et al. (2014). Within each grid box, the scavenging rate, r, is calculated as

where Sj is the scavenging coefficient for precipitation type j and pj(l) is the precipitation rate for type j from model vertical level l. The two precipitation types, j, considered are convective and large-scale types. For nitric acid (HNO3), the scavenging coefficient is taken from Penner et al. (1991). For all remaining species, the scavenging coefficient is calculated by scaling down the scavenging coefficient of HNO3. This is done by calculating the fraction of each species in the aqueous phase as

where L is the liquid water content, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the temperature. Heff is the effective Henry's coefficient, which depends on the solubility of a species and the effects of dissociation and complex formation. The effective Henry's coefficient is calculated as

where ΔH is the enthalpy of vaporisation and k(298) is the rate coefficient at 298 K. The [H+] is the hydrogen ion concentration (i.e. pH). All cloud liquid water droplets are assumed to have a pH of 5.0 (Giannakopoulous, 1998). The kaq is calculated for species which dissociate upon dissolution, and is calculated as

where kd and ΔHd are the rate coefficients and enthalpy of vaporisation for dissociation, respectively.

2.1.2 Gaseous dry deposition

Dry deposition refers to the transfer of chemical species from the atmosphere to the surface in the absence of precipitation. Dry deposition of gas-phase species within UKCA has also been described in detail before (O'Connor et al., 2014) so is only described briefly here. The dry deposition velocity (vd) is calculated using a resistance-based approach (Wesely, 1989). This approach is analogous to an electrical circuit, where the transport of chemical species is dependent on three resistances, ra, rb, and rc:

The aerodynamic resistance term, ra, represents the resistance to transport of chemical species through the boundary layer to a thin layer of air just above the surface. This term is calculated from the wind profile, taking into account the atmospheric stability and the surface roughness

where z is the height, z0 is the roughness length, Ψ is the Businger dimensionless stability function, k is Karman's constant, and u* is the friction velocity.

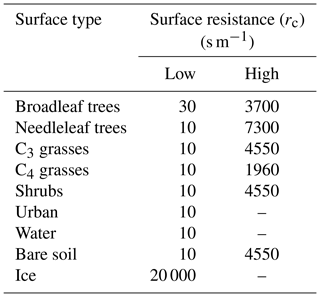

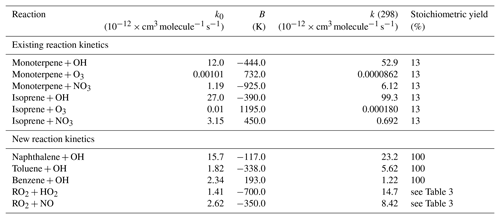

The quasi-laminar resistance term, rb, refers to the resistance to transport though the thin layer of air close to the surface. The surface resistance term, rc, otherwise known as the canopy resistance term, refers to resistance to uptake at the surface. This term is dependent on the absorbing surface as well as the physical and chemical properties of species. The canopy resistance term is related to surface conditions, time of day, and season. There are nine surface types considered by the model. These are broad-leaved trees, needle-leaf trees, C3 and C4 grasses, shrubs, urban, water, bare soil, and land ice. These surface types are prescribed from the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) dataset (Loveland et al., 2000). Within each grid box, the multiple resistances are calculated for each surface type and then combined to provide a grid box mean deposition velocity and first-order loss rate.

2.2 Aerosol (GLOMAP-mode)

The aerosol component of UKCA is the 2-moment modal version of the Global Model of Aerosol Processes (GLOMAP-mode; Mann et al., 2010). Both aerosol mass and number are transported in seven internally mixed log-normal modes (four soluble and three insoluble). Aerosol components considered are sulfate (SO4), sea salt (SS), black carbon (BC), primary organic aerosol (POA), and secondary organic aerosol (SOA). Aerosol microphysical processes included are nucleation, coagulation, condensation, condensation ageing, hygroscopic growth, and cloud processing. Species such as POA and BC are assumed to be emitted in insoluble forms. Condensation ageing refers to soluble vapours condensing on these insoluble POA and BC particles, and thus rendering them soluble. Ten monolayers of soluble particles are assumed sufficient for condensation ageing. No ageing processes are applied to SOA. Dry deposition and gravitational settling of aerosol follows Slinn (1982) and Zhang et al. (2012), respectively. Grid-scale wet deposition of aerosol occurs via nucleation scavenging and impact scavenging. Subgrid-scale wet removal occurs via plume scavenging (Kipling et al., 2013). New particle formation from binary homogenous nucleation of sulfuric acid (H2SO4) follows that described by Kulmala et al. (2006). Gaseous sulfur compounds (sulfur dioxide, SO2, and dimethyl sulfide, DMS) and VOCs are oxidised, forming low-volatility gases, which condense irreversibly onto pre-existing aerosol. Condensation is calculated following Fuchs and Sutugin (1971) which is described in Mann et al. (2010). Mineral dust is also included in the model simulations, but treated in a separate aerosol module (Woodward, 2001).

2.3 Emissions

The emissions used in this study are all monthly-varying decadal-average values centred on the year 2000. Anthropogenic and biomass burning gas-phase emissions are prescribed following Lamarque et al. (2010). Biogenic emissions of isoprene, monoterpene, and methanol (CH3OH) are also prescribed, taken from the Global Emissions Inventory Activity (GEIA), based on Guenther et al. (1995). A diurnal cycle in isoprene emissions is imposed based on solar zenith angle. POA and BC emissions from fossil fuel combustion are prescribed following Lamarque et al. (2010). POA and BC emissions from savannah burning and forest fires are prescribed, taken from the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFEDv2; van der Werf et al., 2010). For VOCBB, monthly-mean CO emissions from biomass burning were used to define its spatial distribution (Lamarque et al., 2010) and scaled to reproduce the global annual VOC total emissions from biomass burning estimated from the Emissions Database for Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) (49 Tg (VOCBB) a−1). For VOCANT, monthly-mean anthropogenic emissions of benzene, toluene, and xylene were taken from Lamarque et al. (2010), and scaled to reproduce the global annual anthropogenic VOC total emissions estimated by EDGAR (127 Tg (VOCANT) a−1). Scaling both VOCBB and VOCANT to the emission type's totals (i.e. biomass burning and anthropogenic, respectively) represents an upper limit for the SOA precursor emissions. The emissions of VOCBB and VOCANT described here have been used in Kelly et al. (2018), with the corresponding impacts on SOA rigorously evaluated against observations. Briefly, the locations of SOA observations are well suited to constrain the anthropogenic source of SOA, but not so well suited for evaluating VOCBB. Inclusion of VOCANT in SOA production gives rise to a substantial improvement in model agreement with observations (Kelly et al., 2018).

2.4 Default treatment of SOA

In this section, the current treatment of SOA in the UKCA model is first described, followed by descriptions of new treatments of precursor deposition and oxidation mechanisms. Within the model, SOA is treated by a coupling between the UKCA gas-phase chemistry and GLOMAP-mode. Emitted parent hydrocarbon gases undergo a single-step oxidation, forming a secondary organic gas (SOG) which condenses, forming SOA. This is shown in Eq. (8),

where VOC is the concentration of the emitted parent hydrocarbon, [o] is the oxidant concentration, kVOC+[o] is the temperature-dependent rate coefficient (Eq. 1), αVOC+[o] is the stoichiometric coefficient, and SOG is the secondary organic gas. SOG is treated as non-volatile, and although there is evidence that organic aerosol (OA) is both semi-volatile (Robinson et al., 2007; Donahue et al., 2012) and non-volatile (Jimenez et al., 2009; Cappa and Jimenez, 2010), SOG condenses irreversibly to form SOA in UKCA. The yield is identical for all oxidation reactions (13 %), regardless of VOC or oxidant. Essentially, the volatility distribution is assumed to be identical for all reactions, irrespective of parent VOC and oxidant. In the model, no SOA precursor undergoes dry or wet deposition.

In this study, SOA production is considered from gas-to-particle partitioning of VOC oxidation products. S/IVOC emissions are not considered and aqueous-phase SOA production is not included. These include monoterpene, isoprene, VOCBB, and VOCANT. Monoterpene and isoprene contain both single and double carbon bonds and therefore react with ozone (O3) and the hydroxyl (OH) and nitrate (NO3) radicals, forming SOG and subsequently SOA (Eq. 8). Note, for isoprene, oxidation in the context of SOA production (Eq. 8) occurs independently to isoprene oxidation in the Mainz Isoprene Mechanism described in Sect. 2.1. Reaction kinetics for isoprene and monoterpene (α-pinene) oxidation are taken from Atkinson and Arey (2003), and are shown in Table 1. As discussed in Sect. 2.4, VOCANT and VOCBB are surrogate compounds, which do not retain molecular information, and therefore do not have laboratory-derived rate constants. Initially, the assumption is made that VOCANT and VOCBB are reduced compounds, with only single carbon bond and react predominantly with OH. VOCANT and VOCBB are also assumed to have a similar reactivity to monoterpene towards OH oxidation, but do not react with O3 or NO3. These assumptions in the parent hydrocarbon reactivity are discussed further in Sect. 2.4.2. As stated above, none of the SOA precursors in this scheme are wet or dry deposited. In summary, the current SOA scheme suffers from a lack of mechanistic detail in oxidation mechanisms, and neglects precursor deposition. In the following subsections, modifications to the model are described and the impacts of these processes quantified.

Table 1Kinetic parameters used to calculate rate coefficient (Eq. 1) for both existing and new SOA precursors, taken from Atkinson and Arey (2003). Note, VOCANT∕BB reacts with OH with reaction kinetics based on either monoterpene, naphthalene, toluene, or benzene.

2.4.1 Addition of SOA precursor deposition

Precursors of SOA include the emitted parent hydrocarbons (monoterpene, isoprene, VOCANT, VOCBB) and the secondary organic product (SOG). Several modifications were made to UKCA to investigate the influence of precursor deposition on SOA. Firstly, wet deposition of the gas-phase species, as described in Sect. 2.1.1, was extended to include all SOA precursors. The effective Henry's law coefficient, for all SOA precursors, was either set to 105 or 109 M atm−1. These values of Heff were taken from estimates by Hodzic et al. (2014). Secondly, the treatment of dry removal of gas-phase species (Sect. 2.1.2) was extended to include all SOA precursors and they were assumed to have identical surface resistances. Table 2 shows the surface resistances for the SOA precursors over the nine surface types. The aerodynamic and quasi-laminar surface resistances were calculated on-line, based on relative molecular mass and meteorology. During field studies over forested regions, organic hydroperoxides (ROOH) were observed to undergo significant dry deposition (Hall et al., 1999; Valverde-Canossa et al., 2006; Nguyen et al., 2015). Surface resistances derived from these field studies range from 5–40 s m−1 (Hall et al., 1999; Nguyen et al., 2015). Hence, these field-derived surface resistances of ROOH (“Low”; Table 2) were used to provide a lower estimate of the surface resistances of SOA precursors. Surface resistances corresponding to the dry deposition of CO (“High”; Table 2) were used to provide an upper limit of the surface resistances of SOA precursors.

2.4.2 Addition of a new oxidation mechanism for VOCANT∕BB

As discussed in Sect. 2.4, initially VOCANT∕BB follows a single-step oxidation mechanism, with a single fixed SOA yield, and with a reactivity based on α-pinene (Table 1). However, of the anthropogenic and biomass burning VOCs related to SOA production, aromatic compounds have been identified as important components in field studies (Von Schneidemesser et al., 2010; Ding et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2013). Furthermore, environmental chamber studies suggest aromatic hydrocarbons undergo multi-generational oxidation reactions, with SOA yields dependent on oxidant concentrations (Ng et al., 2007; Chan et al., 2009; Kautzman et al., 2010; Li et al., 2016, 2017b; Al-Naiema and Stone, 2017; Schwantes et al., 2017). Therefore, in order to examine how SOA is affected by variations in oxidation mechanisms, chamber-derived aromatic oxidation pathways are applied to VOCANT∕BB. This section outlines how the chamber-derived aromatic oxidation pathway, postulated by Ng et al. (2007), is applied to the mechanistic description of SOA production from VOCANT∕BB within UKCA.

Figure 1Formation of lower volatility vapours from toluene photooxidation, as described in Ng et al. (2007).

Figure 1 shows a mechanistic description of SOA production from toluene, accounting for the influence of NOx on SOA production, adapted from Ng et al. (2007). Briefly, toluene undergoes oxidation by OH, followed by addition of oxygen and isomerisation, to form a bicyclic peroxy radical, RO2. The bicyclic peroxy radical undergoes competitive reactions with hydroperoxyl radical (HO2) and NO. The HO2 pathway forms functionalised products, whereas products of the NO pathway are fragmented. Although Fig. 1 shows a mechanistic description of toluene oxidation, the oxidation of other methylated aromatic compounds will also follow a similar pathway. This mechanism for aromatic oxidation, as shown in Fig. 1, was applied to VOCANT∕BB oxidation. The rate determining step in Fig. 1 is the initial oxidation by OH and, therefore, the mechanism can be simplified as follows:

where VOC represents VOCANT∕BB, kVOC+OH represents the rate constant for aromatic oxidation by OH, RO2 represents the bicyclic peroxy radical, and represent the rate constant and the stoichiometric coefficient for the RO2+HO2 reaction, respectively, and and represent the rate constant and the stoichiometric coefficient for the RO2+NO reaction, respectively. Both RO2 reactions form the same non-volatile species, SOG, but the yields associated with the formation rates of this product are variable ( and ). Hence, this mechanism allows the sensitivity of SOA production to HO2 or NO to be accounted for. However, note that the differences in volatility between RO2 oxidation products are not explicitly accounted for. Within the model, the difference in volatility distribution between the products of the RO2 reactions are controlled by the stoichiometric coefficients ( and ). Previous modelling studies use a similar method to treat SOA production via the RO2+HO2 pathway. Assuming that the products from oxidation of explicit aromatic compounds are non-volatile, Henze et al. (2008) use a stoichiometric yield of around 18 %. Using IVOC emissions based on naphthalene, Pye and Seinfeld (2010) use a stoichiometric coefficient of 73 %. However, both Henze et al. (2008) and Pye and Seinfeld (2010) treat products from the RO2+NO pathway as semi-volatile, with stoichiometric yields ranging from 2 % to 107 %, and equilibrium partitioning coefficients ranging from 0.0037 to 3.3150 m3 µg−1. The reaction kinetics for aromatic oxidation used here are shown in Table 1. At 298 K, the rate coefficients for the reaction of OH with naphthalene, toluene, and benzene are 23.2, 5.62, and cm3 molecule−1 s−1, respectively (Table 1). At 298 K, the rate coefficients for the reactions of the peroxy radical with HO2 and NO are 14.7 and cm3 molecule−1 s−1, respectively (Table 1). Note, these rate coefficients are used for the peroxy radical irrespective of the identity of the parent VOC (i.e. naphthalene, toluene, or benzene).

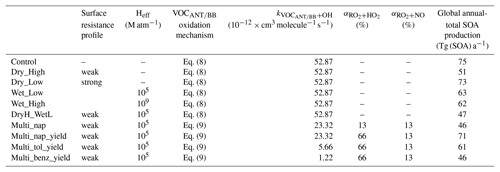

2.5 Model simulations

In this study, 10 simulations were performed to explore the influence of hydrocarbon deposition and oxidation mechanisms on SOA, and are described in Table 3. The duration of all simulations is 2 years, spanning from 1999 to 2000. The first year was discarded as spin-up, and analysis was performed on the second year – 2000. Firstly, a control simulation was conducted, where the oxidation of all parent hydrocarbons (isoprene, monoterpene, VOCANT, and VOCBB) followed Eq. (8) and no SOA precursors were lost by wet or dry deposition processes. Next, the influence of VOC deposition on SOA was explored. To begin with, precursors were assumed to have low surface resistances (Low; Table 2), thus testing the upper limit for precursor dry deposition (Dry_High; Table 3). Next, the strength of precursor surface resistance was increased (High; Table 2), testing the lower limit for deposition rates (Dry_Low; Table 3). Next, SOA precursors were treated as soluble and were, therefore, included in the wet deposition scheme. As with dry removal, the upper and lower limits of precursor wet deposition were tested by carrying out two simulations: one with a higher solubility (Wet_High) and one with a lower solubility (Wet_Low). An additional simulation was conducted to test whether the effects of precursor dry and wet deposition on SOA are additive (DryH_WetL). Note, for this simulation, dry and wet deposition are included with low surface resistances (Low; Table 2) and low solubility. Alternative combinations of surface resistances and solubility could have been used to quantify the combined influence of precursor dry and wet deposition on SOA.

Table 3Simulations conducted in this study. Surface resistances, Low and High, are shown in Table 2. For both surface resistances and Heff, all SOA precursors are assumed to have identical parameters. The oxidation mechanism for isoprene and monoterpene follows Eq. (8) in all simulations. Emissions for all SOA precursors are identical across all simulations.

Next, the influence of VOC oxidation mechanisms on SOA was explored by modifying the mechanistic description of SOA production from anthropogenic and biomass burning VOCs. As discussed in Sect. 1, oxidation mechanisms within SOA schemes vary substantially. Therefore, in this section, where necessary, changes to VOCANT∕BB oxidation were made in a stepwise fashion in order to isolate the effects of individual changes. Firstly, the combined effects of the use of a reactive aromatic compound (naphthalene) and introducing a reaction intermediate (RO2) were explored in the Multi_nap simulation, where VOCANT∕BB follows Eq. (9). In this simulation, stoichiometric reaction yields of 13 % are applied to both RO2 oxidative pathways, which is identical to the reaction yield applied to simulations following the single-step mechanism (Eq. 8). The effects of changes to parent VOCANT∕BB reactivity, the chemical fate of the new reaction intermediate and SOA production from this intermediate are discussed separately in Sect. 5.1.1, 5.1.2, and 5.1.3, respectively. Next, the influence of accounting for the difference in volatility distribution of products between the peroxy radical pathways was accounted for in a further model experiment (Multi_nap_yield), which is discussed in Sect. 5.1.4. This was achieved by increasing the SOA yield from 13 % to 66 % for the HO2 pathway, whilst leaving the reaction yield for the NO pathway unchanged at 13 %. A stoichiometric yield of 66 % was selected as this allows for quantification of the theoretical upper limit of SOA production from this pathway. Note, RO2 and SOG have relative molecular masses of 100 and 150 g mol−1, respectively. Because of these differences in relative molecular masses between reactants and products, the stoichiometric yield applied to the conversion of RO2 and SOG is not equivalent to the mass yield. For example, a stoichiometric yield of 66 % corresponds to a mass yield of 100 %. A mass yield of 100 % would be the case if all reacted RO2 ended up forming non-volatile products (with no addition of oxygen atoms). Next, the influence of parent hydrocarbon reactivity was explored, whilst maintaining identical reaction mechanisms and yields (Sect. 5.1.5). In this simulation, VOCANT∕BB adopts the reactivity of toluene (Multi_tol_yield) and benzene (Multi_benz_yield) (Table 3). Note, for the simulations investigating the influence of oxidation mechanisms on SOA, isoprene and monoterpene oxidation is unchanged. The emissions of all SOA precursors (isoprene, monoterpene, and VOCANT∕BB) are identical in all the simulations.

This section describes the observations used to test the effects of variations in hydrocarbon physicochemical processes on model performance. To make direct comparisons, and provide a consistent method for evaluating model performance, a suite of observations were chosen which are identical to those used in previous studies involving the UKCA model (Kelly et al., 2018).

The aerosol mass spectrometer (AMS) allows on-line detection of submicron non-refractory aerosol (Jayne et al., 2000; Canagaratna et al., 2007). This method was used to measure OA concentrations for all observations utilised in this study. Uncertainties associated with this method are estimated to be between 30 % and 50 % (Bahreini et al., 2009). All observations used in this study can be accessed on the AMS global network website (https://sites.google.com/site/amsglobaldatabase/, last access: 3 June 2019).

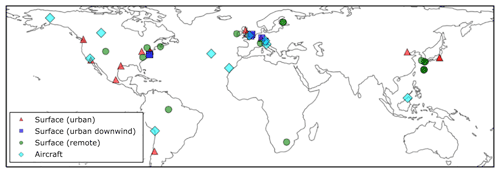

Surface OA observations from the AMS network, originally compiled by Zhang et al. (2007), span the time period 2000–2010. The 37 observed surface measurement locations are shown in Fig. 2 and coloured according to the environment sampled: urban, urban downwind, or remote. With the exceptions of Manaus (Brazil; Martin et al., 2010) and Welgegund (South Africa; Tiitta et al., 2014), all surface OA spectra were analysed further using factor analysis, classifying OA as either oxygenated OA (OOA) or hydrocarbon-like OA (HOA). Here, measured OOA is assumed comparable to modelled SOA, and measured HOA is assumed comparable to POA. For each observation, the corresponding model-grid box was selected. Also, observations were compared to the simulated monthly-mean from the year 2000.

Figure 2Global map showing the 40 surface AMS observations, originally compiled by Zhang et al. (2007) and classified as urban (red triangles), urban downwind (blue squares), or remote (green circles). Of the surface observations, 37 have been classified as hydrocarbon-like OA and oxygenated OA. Observations from 10 aircraft campaigns, originally compiled by Heald et al. (2011), are also shown (light-blue diamonds); these remain as total OA.

Observed OA concentrations from several aircraft campaigns were also used. Observation data from these aircraft campaigns, which were originally compiled by Heald et al. (2011), can also be accessed on the AMS global network website (https://sites.google.com/site/amsglobaldatabase/, last access: 3 June 2019). Aircraft observations utilised in this study are also shown in Fig. 2. These campaigns span the period 2000–2010. Four campaigns were carried out in remote regions, located over the north Atlantic Ocean (TROMPEX and ITOP), Borneo (OP3), and the tropical Pacific Ocean (VOCALS-UK). Three campaigns were also carried out in polluted regions of Europe (EUCAARI, ADIENT, and ADRIEX). Three campaigns were carried out in North America and were influenced heavily by biomass burning (ARCTAS-A, ARCTAS-B, and ARCTAS-CARB). This observational dataset was supplemented with a campaign conducted over West Africa (AMMA; Capes et al., 2008). Observed OA from each aircraft campaign was first interpolated onto the vertical grid of the model. The model's horizontal grid cell was then matched to the observations. Again, the month of the observations were matched to the monthly mean estimate for the year 2000 simulated by UKCA. For evaluations of surface and aircraft data against simulated OA concentrations, the mismatch in measurement and simulation years is a potential contributor to the model–observation bias. This mismatch in time may be particularly important for regions influenced by biomass burning as the interannual variability in this emissions source is substantially high (Tsimpidi et al., 2016).

In this section, the influence of VOC deposition (Sect. 2.4.1) on simulated SOA is quantified. Next, the influence of VOC deposition on model agreement with observations is evaluated.

4.1 Simulated SOA budget and concentrations

When precursor deposition is neglected from the model, the simulated global annual-total SOA production rate is 75 Tg (SOA) a−1 (Control; Table 3). The inclusion of VOC dry deposition with high surface resistances (High; Table 2) reduces the global annual-total SOA production rate by only 2 Tg (SOA) a−1 (2 %) (Dry_Low; Table 3). However, the rate of VOC dry deposition is highly sensitive to the value of surface resistance. The inclusion of VOC dry deposition with lower surface resistances (Low; Table 2) reduces the global annual-total SOA production rate by 24 Tg (SOA) a−1 (32 %) (Dry_High; Table 3). Therefore, inclusion of precursor dry deposition reduces the global annual-total SOA production rate by 2–24 Tg (SOA) a−1, or 2 %–32 %, with this range reflecting uncertainties in surface resistances (Table 3).

Wet removal also has a substantial impact on SOA. For example, under the assumption of an effective Henry's coefficient of 105 M atm−1, wet deposition reduces the global annual-total SOA production rate by 12 Tg (SOA) a−1 (15 %) compared to when no precursors undergo deposition (Wet_Low; Table 3). However, as discussed in Sect. 1, Heff has been calculated to range from 105 to 109 M atm−1 for VOC precursors of SOA from different sources (Hodzic et al., 2014). In this study, when Heff of SOA precursors is increased to 109 M atm−1, wet removal reduces the global annual-total SOA production rate by only 13 Tg (SOA) a−1 (17 %) (Wet_High; Table 3). Therefore, the influence of precursor wet deposition on SOA is rather insensitive to uncertainties in the range of effective Henry's coefficients.

Generally, global- (Hodzic et al., 2016) and regional-scale modelling studies (Bessagnet et al., 2010; Knote et al., 2015) suggest that dry deposition of precursor dominates over wet deposition. Therefore, for subsequent simulations, where both dry and wet removal were included in the model (DryH_WetL), surface resistances corresponding to Dry_High, which had the largest impact on global SOA production, were used, along with Heff of 105 M atm−1 (Wet_Low). The influence of dry and wet deposition of precursors on the global SOA budget are not additive. The combination of dry and wet deposition of VOCs reduces the global annual-total SOA production rate by 28 Tg (SOA) a−1 (37 %) (DryH_WetL; Table 3). Overall, deposition of SOA precursors has a substantial impact on the global SOA budget, with the global annual-total SOA production rate from all VOC sources ranging from 47 to 75 Tg (SOA) a−1, with the range reflecting uncertainties in precursor deposition (Table 3).

Prior to including deposition of SOA precursors, biogenic VOCs account for 57 % of the global annual-total SOA production rate, with VOCANT∕BB accounting for the remaining 43 %. By including deposition of SOA precursors, the relative importance of biogenic VOCs to global SOA increases; considering deposition of SOA precursors, biogenic VOCs account for 62 % of the global annual-total SOA production rate with VOCANT∕BB accounting for the remaining 38 %. Hence, biogenic VOCs appear to be less susceptible to deposition than anthropogenic and biomass burning VOCs.

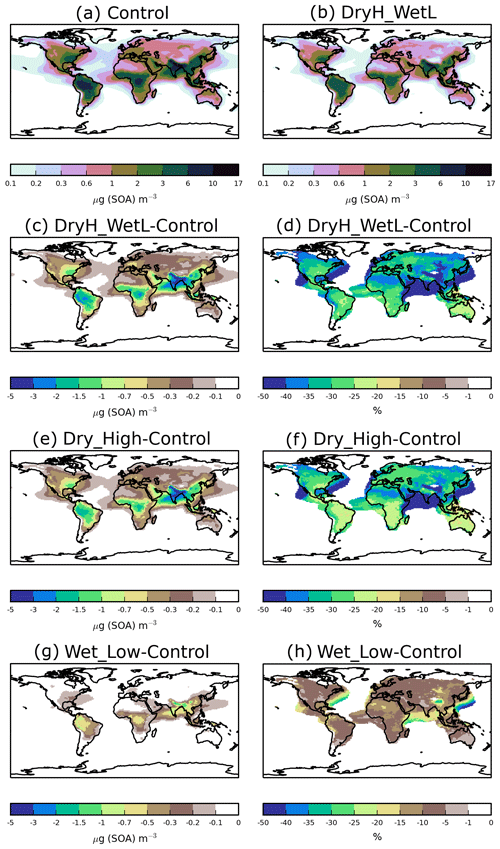

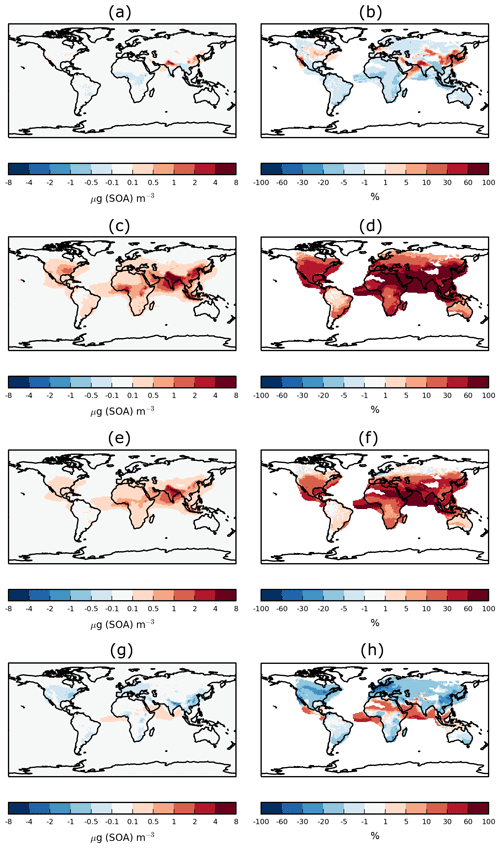

Figure 3 shows the sensitivity of annual-average surface SOA concentrations to precursor deposition. The spatial distribution of SOA closely reflects the location of biogenic, anthropogenic, and biomass burning emissions, as noted previously (Kelly et al., 2018). Over India, extremely high anthropogenic emissions combine with moderate biogenic emissions to result in annual-average surface SOA concentrations reaching up to 17 µg (SOA) m−3 (Fig. 3a). Over tropical forest regions of South America and Africa, biogenic and biomass burning emissions are extremely high, resulting in annual-average surface SOA concentrations ranging from 2 to 10 µg (SOA) m−3 (Fig. 3a). Over Europe and North America, moderate emissions from anthropogenic and biogenic sources generate annual-average surface SOA concentrations in the range of 0.3–6 µg (SOA) m−3 (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3Annual-average surface SOA concentrations for (a) Control and (b) DryH_WetL simulations, and absolute and percentage differences in annual-average surface SOA concentrations for (c, d) DryH_WetL, (e, f) Wet_Low, and (g, h) Dry_High simulations relative to Control.

Over India and tropical forest regions of South America and Africa, including VOC dry deposition reduces annual-average surface SOA concentrations by 1.5 to 5 µg (SOA) m−3 (Fig. 3e), corresponding to reductions of 15 % to 50 % (Fig. 3f). Over these same regions, inclusion of precursor wet deposition reduces annual-average surface SOA concentrations by 0.5 to 1.5 µg (SOA) m−3 (Fig. 3g), corresponding to reductions of 5 %–10 % (Fig. 3h). Over North America, annual-average surface SOA concentrations are reduced by 0.3–1.5 µg (SOA) m−3 when precursor dry removal is included (Fig. 3e), corresponding to a reduction of around 20 % to 35 % (Fig. 3f). Over Europe, dry deposition lowers annual-average surface SOA concentrations by around 0.2 µg (SOA) m−3 (25 %–40 %, Fig. 3e, f). Over both North America and Europe, the inclusion of wet deposition reduces annual average surface SOA concentrations by less than 0.2 µg (SOA) m−3 (Fig. 3g), but this corresponds to reductions of 20 % to 35 % (Fig. 3h).

Until now, the impacts of precursor deposition on SOA concentrations have only been quantified over Europe (Bessagnet et al., 2010) and North America (Knote et al., 2015), both of which use regional-scale models and treat SOA as semi-volatile. Note, Bessagnet et al. (2010) treat SOA formation by a single-step oxidation of parent VOC followed by reversible condensation into the aerosol phase. Knote et al. (2015) treat SOA formation using the volatility basis set (VBS). The sensitivity of SOA to precursor dry removal is in broad agreement with Bessagnet et al. (2010), who estimate that precursor dry deposition reduces July-average surface SOA concentrations by 20 %–40 % over Europe compared to 25 %–35 % for the same period in our study. Also, Knote et al. (2015) estimate that precursor dry deposition reduces annual-average surface SOA concentrations by 46 % over North America, compared to up to 20 %–35 % in our study. The modelled sensitivity of SOA concentrations to wet deposition in this study is in relatively good agreement with Knote et al. (2015), who estimate a 10 % reduction in annual-average surface SOA concentrations over North America when precursor wet deposition is included, which agrees with the 5 %–15 % reduction found here.

When dry and wet removal of VOC precursors are both included, SOA concentrations are substantially lower. However, as noted before, the effects of these removal processes do not add linearly. Inclusion of both dry and wet deposition of SOA precursors reduces annual-average surface SOA concentrations by 25 %–40 % over most continental regions (Fig. 3d), with maximum reductions of 5 µg (SOA) m−3 over India (Fig. 3c).

The lifetime of SOA precursors with respect to both oxidation and deposition is small. Hence, SOA precursors undergo very little transport before removal. Therefore, dry and wet deposition rates of VOCs are largest over terrestrial environments, where they are released. Across these simulations where the deposition of SOA precursors is altered, the global-average annual-average SOA lifetime varies from 4.3 to 4.7 d (not shown).

4.2 Comparison of simulated and observed OA concentrations

In this section, the influence of SOA precursor deposition on model agreement with observations is quantified. First, simulated SOA and OA concentrations are evaluated against surface observations in the Northern Hemisphere (NH) and Southern Hemisphere (SH), respectively. Next, vertical profiles of simulated OA concentrations are compared against aircraft observations.

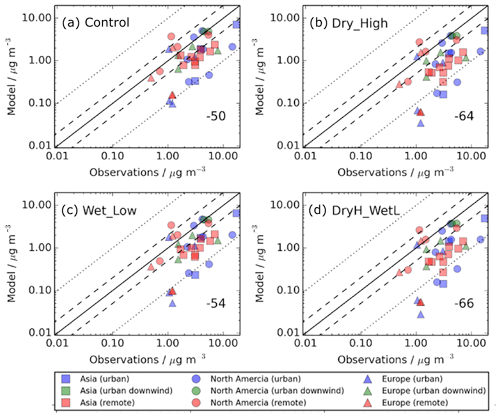

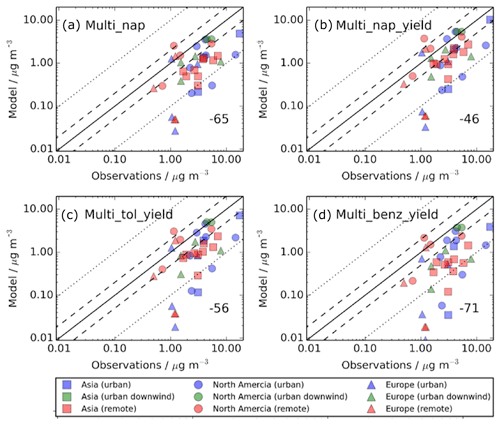

Figure 4 shows SOA concentrations for the simulations described in Table 2 compared to observed surface SOA concentrations across the NH mid-latitudes, which are shown in Fig. 2. Observed SOA concentrations are in the form of averages over the campaign period (which ranges from a few days to 1 year), and span from 2000 to 2010. These observed concentrations are then matched to the grid box which they fall in, with the simulated monthly averages being selected for the year 2000. Hence, there is a mismatch in terms of the measurement year and the simulated year. When deposition of SOA precursors is omitted from the model, simulated SOA concentrations are substantially lower than observed, with a normalised mean bias (NMB) of −50 % (Fig. 4a). The model negative bias is present for each site-environment type but most evident in urban environments. For several sites in urban environments, observed SOA concentrations exceed simulated SOA concentrations by greater than a factor of 10 (Fig. 4a – red triangles). The model negative bias is also consistent regionally. Without SOA precursor deposition, the NMBs for Europe, North America and Asia is −50 %, −37 % and −62 %, respectively.

Figure 4Simulated versus observed surface SOA concentrations (µg m−3) for (a) Control, (b) Dry_High, (c) Wet_Low, and (d) DryH_WetL simulations, described in Table 3. Observations, originally compiled by Zhang et al. (2007), for the time period 2000–2010, are classified by site type – urban (blue), urban downwind (green), or remote (red) – and continent – Asia (squares), North America (circles), and Europe (triangles). Observed oxygenated OA is assumed to be comparable to simulated SOA. The 1 : 1 (solid), 1 : 2 and 2 : 1 (dashed), and 1: 10 and 10 : 1 (dotted) lines are indicated. Numerical values in the bottom right of each panel indicate the normalised mean bias (%).

The model negative bias with respect to observed SOA concentrations is common among global models (Tsigaridis et al., 2014). For several modelling studies, the negative bias is primarily attributed to either underestimated reaction yields, underestimated emissions, and/or missing emission sources. Hodzic et al. (2016) partially attributes the model negative bias with respect to observations to laboratory-derived SOA yields which do not account for wall losses. Other studies highlight VOC emission uncertainties such as underestimates in inventories (Li et al., 2017a) or the absence of semi- and intermediate-volatility organic compounds (S/IVOCs) which can contribute to SOA (Pye and Seinfeld, 2010), both of which are not included in this study.

Inclusion of precursor deposition further reduces model agreement with observations. As discussed in Sect. 4.1, including VOC dry deposition reduces the global annual-total SOA production rate by 32 % (24 Tg (SOA) a−1), whereas including VOC wet deposition reduces SOA production by 15 % (12 Tg (SOA) a−1) (Table 3). Therefore, the model negative bias is larger when including dry deposition (NMB %; Fig. 4b) compared to that when including wet deposition (NMB %; Fig. 11c). However, as the effects of VOC precursor dry and wet removal on simulated SOA are not additive, model performance is not substantially worse when both wet and dry deposition are considered (NMB %; Fig. 4d). When the measurement sites are categorised by region, with both dry and wet removal included, the NMBs across Europe, North America, and Asia are −66 %, −53 %, and −77 %, respectively.

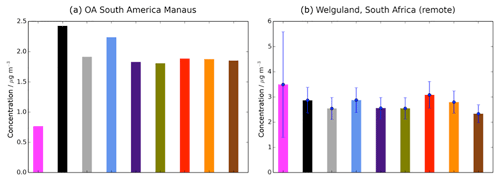

Observed and simulated OA are shown in Fig. 5 for two sites in the tropics and SH, over Manaus (Brazil) and Welgegund (South Africa). Without precursor deposition, simulated SOA is overestimated compared to observed OA over Manaus (Brazil) (Fig. 5a), but underestimated over Welgegund (South Africa) (Fig. 5b). Therefore, inclusion of precursor deposition improves model performance over Manaus (Brazil) (Fig. 5a) but not over Welgegund (South Africa) (Fig. 5b). However, the scarcity of observations in the tropics and the SH result in difficulty in drawing robust conclusions on the influence of precursor deposition on model agreement with observations in this region.

Figure 5Simulated and observed OA surface concentrations (µg m−3) over remote sites in the SH, (a) Manaus (Brazil), and (b) Welgegund (South Africa). Bars indicate OA concentrations from observed (pink) and simulated from the Control (black), Dry_High (grey), Wet_Low (blue), DryH_WetL (purple), Multi_nap (green), Multi_nap_yield (red), Multi_tol_yield (yellow), and Multi_benz_yield (brown) simulations, described in Table 3. For Welgegund, both observed and simulated monthly mean OA concentrations span an entire year. The standard deviations across this year, based on the monthly-mean data, are indicated in blue. For Manaus, however, the measurements of OA only span 1 month, hence no standard deviation is shown for this site.

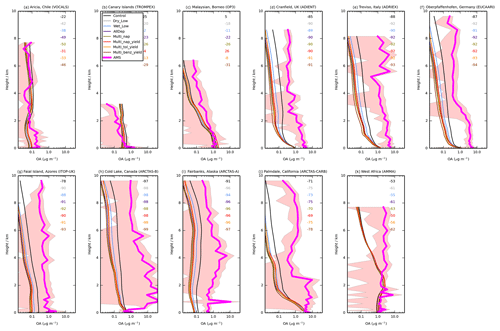

Figure 6 shows the simulated OA vertical profiles against the AMS aircraft measurements. Without precursor deposition, model negative biases are again evident and are largest in polluted and biomass-burning-influenced regions in the NH. For example, over Europe (ADIENT, ADRIEX, and EUCAARI) and North America (ARCTAS-A, ARCTAS-B and ARCTAS-CARB), OA concentrations are underestimated by 71 % (ARCTAS-CARB; Fig. 6j) to 97 % (ARCTAS-B; Fig. 6h) when considering all altitudes. When VOC precursors of SOA do not undergo deposition, over western Africa, simulated OA concentrations are in good agreement between 0 and 3 km (Fig. 6k). However, above 3 km, model and simulated OA concentrations begin to deviate, with observed OA increasing with altitude, but modelled OA decreasing with altitude (Fig. 6k). When considering all altitudes of the AMMA campaign, modelled and measured OA concentrations are in fairly good agreement with a NMB of −53 % (Fig. 6k).

Figure 6Mean vertical profile of OA (µg m−3) from 11 field campaigns (pink) with monthly mean modelled OA from UKCA for the simulations described in Table 3. The standard deviation of the binned observations at each model layer is shown (peach envelope). For each campaign, the normalised mean bias (%) for each simulation is also included in the top right of each panel.

Over North America and Europe, including precursor deposition slightly worsens the model negative bias. When both precursor dry and wet deposition are included, the model underestimates observed OA concentrations by 75 % (ARCTAS-CARB; Fig. 6j) to 98 % (ARCTAS-B; Fig. 6h). Over West Africa, when VOC precursors of SOA undergo deposition, the model underestimates observed OA concentrations by 61 % (Fig. 6k).

Compared to other environments, in remote regions, model agreement with observations is relatively good, and the inclusion of precursor deposition results in both improvements and degradations in model biases in simulated OA compared to observations. Without SOA precursor deposition, simulated OA levels in VOCALS and ITOP-UK, similar to the pollution and biomass burning influenced regions, are much lower compared to observed OA (NMB % and −78 %; Fig. 6a and g, respectively). Therefore, inclusion of precursor deposition further reduces model agreement with observations (NMB % and −91 %; Fig. 6a and g, respectively). In contrast, for the TROMPEX and OP3 campaigns, when precursor deposition is neglected, simulated OA is higher than observed (NMB =25 % and 5 %; Fig. 6b and c, respectively). Inclusion of precursor deposition at these locations changes the model positive bias into a negative bias (NMB % and −22 %; Fig. 6b and c, respectively). For all aircraft campaigns conducted in remote environments, generally, simulated OA lies within one standard deviation of the observed concentration, irrespective of whether deposition of precursors is considered or not.

Overall, the inclusion of precursor deposition influences model agreement with observations somewhat. In particular, inclusion of precursor deposition worsens model negative biases with respect to observations in the NH mid-latitudes. However, differences between simulated OA concentrations from these simulations is substantially less than the difference between simulated and observed OA. These results highlight that variations in VOC deposition contribute to considerable uncertainty in both the global SOA budget and have some impact on model agreement with observations.

In this section, the sensitivity of SOA to hydrocarbon oxidation mechanisms is quantified. Here, oxidation mechanisms for anthropogenic and biomass burning VOCs are modified as described in Sect. 2.4.2. To begin with, the influence of anthropogenic and biomass burning VOC oxidation mechanisms on simulated SOA is explored. Next, the impact on model agreement with observations is evaluated. In all simulations, deposition of SOA precursors is included (Table 3), emissions of all SOA precursors are held constant, and the mechanistic description describing the oxidation of biogenic SOA precursors (monoterpene and isoprene) is held fixed, following Eq. (8).

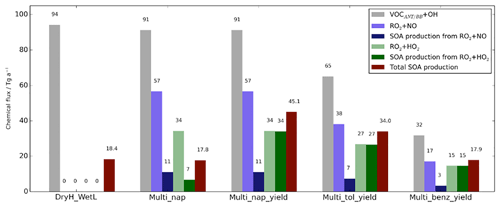

Figure 7Global annual-total reaction fluxes and total SOA production rate from anthropogenic and biomass burning hydrocarbons for the simulations described in Table 3. The global annual-total VOCANT∕BB emission rate, of 176 (VOCANT∕BB) a−1, is identical across all simulations.

5.1 Simulated SOA budget and concentrations

Firstly, the single-step oxidation mechanism of VOCANT∕BB with reactivity based on α-pinene and a fixed reaction yield of 13 % is described (DryH_WetL). The global annual-total reaction fluxes and SOA production rates from anthropogenic and biomass burning hydrocarbons are shown in Fig. 7. As described in Sect. 2.3, the global annual-total VOCANT∕BB emission rate is 176 (VOCANT∕BB) a−1, which is held fixed across all simulations. In this case, the global annual-total VOCANT∕BB oxidation rate by OH is 94 Tg (VOC) a−1 (DryH_WetL; Fig. 7). The remaining 82 Tg (VOC) a−1 undergoes deposition (not shown). For this single-step mechanism, oxidation of the emitted parent hydrocarbon directly forms the non-volatile product, SOG, which condenses almost immediately. A fixed reaction yield of 13 % is assumed, resulting in a global annual-total SOA production rate of 18.4 Tg (SOA) a−1 (Fig. 7). Note, due to differences in relative molecular masses for VOCANT∕BB and SOG, the stoichiometric yield is not equivalent to the mass yield. Expressed as a fraction of emitted parent VOC (176 Tg (VOC) a−1), the overall yield of SOA production from anthropogenic and biomass burning VOCs (18.4 Tg (SOA) a−1) is around 10 %.

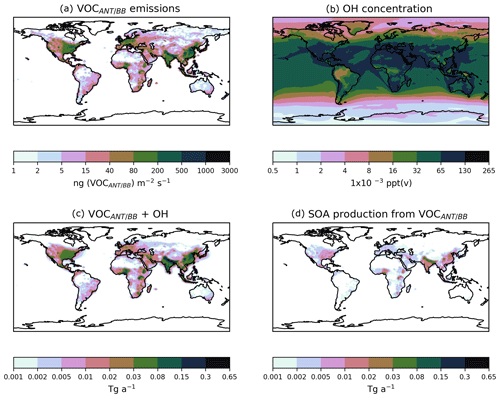

The combination of a single-step oxidation mechanism and the assumption of a relatively reactive parent hydrocarbon results in rapid production of SOA. Figure 8 shows the spatial distributions of annual-total surface VOCANT∕BB emissions, annual-average surface OH concentrations, annual-total vertically integrated oxidation rates, and the resulting SOA production rates. As expected, the spatial distributions of VOCANT∕BB emissions mainly reflects anthropogenic activity. Over high emissions regions, OH concentrations are also relatively high. Over India, China, Europe, and North America, annual-average OH concentrations are in the range of 32– ppt(v) (Fig. 8b). Therefore, for most major VOCANT∕BB emissions source regions, OH availability is high, resulting in rapid oxidation; reaction fluxes of peak very close to emissions sources (cf. Fig. 8a, c). However, uncertainty in simulated OH concentrations will be translated into uncertainty in SOA production. OH is the principal oxidising agent of the atmosphere. Therefore, in order to successfully model OH, many other species (e.g. methane) also need to be modelled correctly (Lelieveld et al., 2016). Due to its very short lifetime (∼ seconds) and low concentrations, OH is difficult to measure (Stone et al., 2012). Alternatively, the OH concentration can be constrained indirectly from the CH4 lifetime. Overall, the OH concentration is a difficulty quantity to capture in a global model.

Figure 8Global distributions of (a) the annual-total VOCANT∕BB emission rate (ng (VOCANT∕BB) m−2 s−2), (b) the annual mean surface OH concentrations (ppt(v)), (c) the annual-total vertically integrated VOCANT∕BB oxidation rate by OH (Tg a−1), and (d) the corresponding annual-total SOA production rate (Tg a−1), when SOA precursor deposition and a single oxidation step with a yield of 13 % is applied (DryH_WetL; Table 3).

Also, as shown in Eq. (8), oxidation of the parent VOC results in immediate production of the condensing species, SOG. Hence, not only do parent VOCs undergo rapid oxidation, but the product of this reaction is in the form of condensable organic vapours. Therefore, this combination of high parent VOC reactivity with few reaction steps results in extremely localised SOA production from anthropogenic and biomass burning emissions. This is in contrast to other global modelling studies, which predict more regionally distributed SOA production (Pye and Seinfeld, 2010; Tsimpidi et al., 2016). Differences in the geographical extent to which SOA production occurs may be attributed to precursor reactivity and the number of reaction intermediates. For example, here, the parent hydrocarbon is a VOC, with a rate constant of cm3 molecule−1 s−1 at 298 K (Table 1), forming SOA in a single-step reaction mechanism. Hence, local SOA production is simulated (Fig. 8d). Conversely, SOA production is more regionally distributed when treated from S/IVOC multi-generational chemistry, where the parent hydrocarbon and oxidation products all react relatively slowly (Tsimpidi et al., 2016). High observed OA concentrations over remote regions (Boreddy et al., 2015, 2016) provide evidence for the slow and sustained mechanistic description of SOA production from S/IVOCs (Tsimpidi et al., 2016). High observed OA concentrations within industrialised emissions source regions (Zhang et al., 2007) support the fast mechanistic description of SOA production from VOCs simulated here.

To summarise, the combination of fast reactivity and a single-step oxidation mechanism favours extremely localised SOA production, with parent VOCs undergoing rapid oxidation and subsequent condensation close to source.

In the following subsections, SOA formation mechanisms are altered, including introducing a reaction intermediate, accounting for the influence of oxidants on SOA yields, and reducing the chemical reactivity of the parent VOC (Eq. 9; Sect. 2.4.2). This begins with an evaluation of the mechanism with the reaction intermediate and with reactivity based on naphthalene (Multi_nap) and how this mechanism compares to the single-step oxidation mechanism with reactivity based on α-pinene (DryH_WetL). For this comparison, the individual effects of reduced parent VOC reactivity, introduction of the reaction intermediate, and SOA production from the reaction intermediate, are evaluated separately in Sect. 5.1.1 to 5.1.3. Next, the effects of accounting for the difference in volatility between RO2 oxidation products is evaluated (Multi_nap_yield) in Sect. 5.1.4. Finally, less reactive parent hydrocarbons are explored in Sect. 5.1.5 (Multi_tol_yield and Multi_benz_yield).

5.1.1 Initial OH oxidation of parent hydrocarbon

Production of SOA from anthropogenic and biomass burning hydrocarbons is modified in the following subsections to follow the mechanism of Eq. (9) which include the reaction intermediate. Naphthalene, the most reactive aromatic VOC considered in this study, is first selected (Sect. 2.4.2), with identical reaction yields applied to both RO2 pathways (Multi_nap simulation; Table 3).

The initial reaction of VOCANT∕BB with OH is compared to that of a single oxidation reaction step (DryH_WetL; Table 3). At 298 K, the rate constants for α-pinene and naphthalene oxidation by OH are 52.9 and cm3 molecule−1 s−1, respectively (Tables 1 and 3). The global annual-total VOCANT∕BB oxidation rate reduces by 3 Tg (VOC) a−1 (or 3 %), from 94 Tg (VOC) a−1 using the reactivity of α-pinene to 91 Tg (VOC) a−1 using the reactivity of naphthalene (Fig. 7). Therefore, the global VOCANT∕BB oxidation rate is relatively insensitive to a ∼50 % reduction in reactivity. When applying a 13 % stoichiometric yield to this reaction sequence (Table 3), this reduction in parent VOC oxidation rate contributes to a marginal change in the global annual-total SOA production rate (0.6 Tg (SOA) a−1).

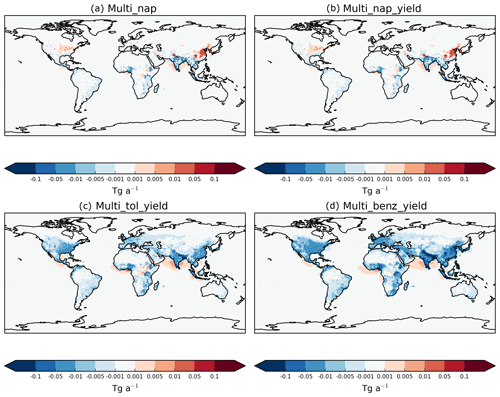

Figure 9Global distribution of the absolute differences in annual-total vertically integrated VOCANT∕BB oxidation rates (Tg (VOC) a−1) in (a) the Multi_nap, (b) the Multi_nap_yield, (c) the Multi_tol_yield, and (d) the Multi_benz_yield simulations relative to the DryH_WetL simulation.

The response of regional VOC oxidation rates to a ∼50 % reduction in the reactivity vary in both magnitude and sign. Figure 9 shows the difference in annual-total vertically integrated VOCANT∕BB oxidation rates for the mechanism which include the reaction intermediate (Table 3), relative to the mechanism which does not include the reaction intermediate with reactivity based on α-pinene (DryH_WetL; Table 3). Reduced chemical reactivity lowers oxidation rates within emission source regions. For example, over India and parts of Africa, annual-total VOCANT∕BB oxidation rates reduce by up to 0.05 Tg (VOCANT∕BB) a−1 (Fig. 9a); these changes in annual-total VOCANT∕BB oxidation rates within emissions source regions correspond to reductions between 10 % and 30 % (not shown). By contrast, downwind of many emissions source regions, the lower reactivity acts to enhance VOCANT∕BB oxidation rates. For example, over the Arabian Sea, over southeast China, off the coast of Nigeria, and over the southeast USA, annual-total VOCANT∕BB oxidation rates increase by 0.001–0.05 Tg (VOCANT∕BB) a−1 in response to a ∼50 % reduction in parent VOC reactivity (Fig. 9a). These changes in annual-total VOCANT∕BB oxidation rates downwind of emissions source regions correspond to reductions which exceed 60 % (not shown). As discussed in Sect. 5.1, adoption of the reactivity of α-pinene for the reaction results in peak VOC oxidation rates at emission source, with VOCs undergoing very little transport (Fig. 8c). Therefore, by reducing the reactivity by ∼50 %, fewer VOCANT∕BB are oxidised at source but transport of VOCANT∕BB away from source is promoted.

5.1.2 Chemical fate of the new reaction intermediate, RO2

Oxidation of the parent VOC forms a new reaction intermediate, the peroxy radical RO2. In this case, VOCANT∕BB oxidation results in a global annual-total peroxy radical production rate of 91 Tg (RO2) a−1 (Multi_nap simulation; Fig. 7). Introduction of this new reaction intermediate has the potential to either reduce and/or delay SOA production, depending on assumptions regarding the strength of deposition and chemical reactivity of this intermediate. For example, SOA production would be reduced if the peroxy radical undergoes significant deposition, which is dependent on deposition parameters such as surface resistances and solubility (Sect. 2.4.1). Additionally, SOA production could be reduced or delayed if the chemical removal of RO2 is slow. The influence of introducing the peroxy radical as a reaction intermediate is therefore predetermined by assumptions in deposition parameters and reaction kinetics. In all simulations, RO2 is assumed to have identical solubility and surface resistances to all other SOA precursors, Heff=105 M atm−1 and “Low” surface resistances (Table 2). At 298 K, the rate constants for RO2 oxidation by HO2 and NO, taken from Atkinson and Arey (2003), are 14.8 and cm3 molecule−1 s−1, respectively (Table 1). Consequently, of the 91 Tg of RO2 generated annually, oxidation by NO and HO2 removes 57 and 34 Tg (RO2) a−1, respectively (Multi_nap_yield; Fig. 7). Deposition of RO2 is inconsequential at 0.1 Tg (RO2) a−1 (not shown). This extremely low deposition rate is because the chemical removal of the peroxy radical is extremely fast. The global annual-average lifetime of RO2 with respect to oxidation is ∼1 d, which is relatively short in comparison to atmospheric transport timescales. Note, a review of laboratory studies suggests the lifetime of RO2 could be of the order of minutes (Orlando et al., 2012). Therefore, due to marginal deposition and fast oxidation, introduction of the peroxy radical reaction intermediate will probably have no effect on either the SOA production rate or the geographical distribution of SOA production, which are both quantified in the following Sect. 5.1.3.

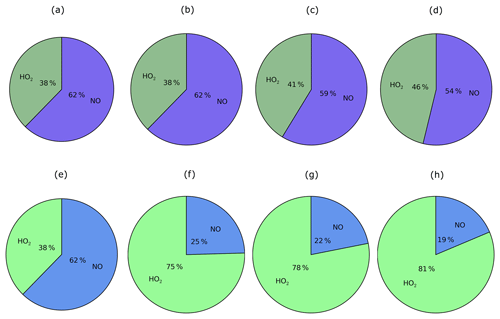

Figure 10For the peroxy radical, chemical removal (top row; a–d) and SOA production (bottom row; e–h) for the Multi_nap (first column; a, e), Multi_nap_yield (second column; b, f), Multi_tol_yield (third column; c, g), and Multi_benz_yield (fourth column; d, h) simulations, which are described in Table 3.

Chemical removal of the peroxy radical via the two oxidative pathways is an important factor in governing the strength of SOA production, as discussed later in Sect. 5.1.3 to 5.1.5. RO2 is chiefly removed by NO, as opposed to HO2 radicals. This is demonstrated in Fig. 10, which shows the relative contributions of the HO2 and NO peroxy radical oxidative pathways to the total chemical removal of RO2 (top row) and to SOA production (bottom row). On a global and annual mean basis, removal by NO accounts for 62 % of RO2 chemical loss (Fig. 10a). Other global modelling studies, which consider the peroxy radical as a reaction intermediate from aromatic compounds or IVOCs, also predict RO2 removal to be dominated by NO. Henze et al. (2008) estimate that 61 % react via the NO pathway for peroxy radicals generated from benzene, xylene, and toluene. For peroxy radicals generated from IVOCs with parent hydrocarbon reactivity based on naphthalene, 66 % are consumed by NO (Pye and Seinfeld, 2010). These results suggest that the chemical fate of the peroxy radical is robust despite the likelihood of variations in precursor emissions and oxidant concentrations between this and the aforementioned studies.

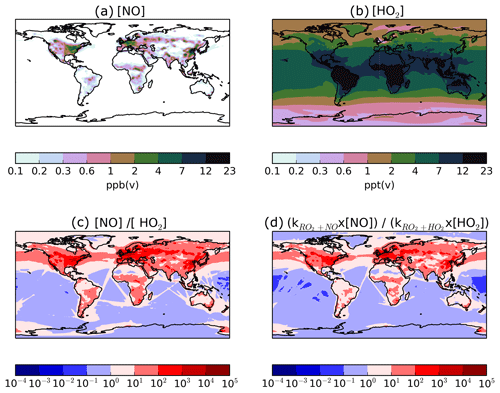

Figure 11Global distributions of annual-average (a) surface NO concentrations (ppb(v)), (b) surface HO2 concentrations (ppt(v)), (c) the ratio of surface NO∕HO2, and (d) the ratio of surface , where k represents the rate coefficient at 298 K. Note that the concentrations of the HO2 radical are in units of parts per trillion by volume, whereas NO is in units of parts per billion by volume.

The substantial preference for RO2 radicals to react via the NO pathway instead of the HO2 pathway can be attributed to differences in oxidant availability (i.e. concentrations) and in reaction rates. Note, in the UKCA model, HO2 is assumed to undergo wet removal. Firstly, consider the difference in oxidant levels. Figure 11 shows the spatial distribution of annual-average surface concentrations of NO and HO2, as well as the ratios NO∕HO2 and . NO is extremely spatially heterogeneous (Fig. 11). Within the model, sources of NOx include the prescribed anthropogenic, biomass burning, and soil emissions, as well as lightning NOx which is calculated interactively. At the surface, the highest annual-average surface NO concentrations (1–23 ppb(v)) are simulated over industrialised and urban regions of North America, China, and Europe (Fig. 11a). Over remote marine environments, away from anthropogenic and biomass burning sources, concentrations of NO are low (Fig. 11a). In contrast, concentrations of HO2 are much lower and more evenly distributed across the surface (Fig. 11). Over the majority of both continental and marine regions, annual-average surface HO2 concentrations range between 2 and 23 ppt(v) (Fig. 11b). Therefore, over most environments, NO concentrations are far greater, with annual-average surface NO concentrations ranging from 10 (NO∕HO2 =101) to 10 000 times more than HO2 (Fig. 11c). Only in the remote marine environments are HO2 levels higher in absolute magnitude compared to NO, with simulated annual-average surface HO2 concentrations reaching 10 times that of NO (NO∕HO2 ; Fig. 11c). At higher levels, NO∕HO2 reduces, suggesting an increasing importance of the HO2 pathway at higher altitudes. However, due to the fast chemical reactivity, the majority of SOA production occurs at the surface. High-altitude emissions of VOCs from biomass burning plumes may be more susceptible to forming RO2 which react with HO2. However, in this study, all VOCANT∕BB are emitted at the surface. For the majority of the atmosphere, the difference in the magnitudes of the oxidant concentrations favours the RO2+NO pathway over the RO2+HO2 pathway.

Differences in reactivity of RO2 with respect to the oxidants also affects the fate of this radical. At 298 K, the rate constant for RO2+NO is cm3 molecule−1 s−1, almost half that of RO2+HO2 cm3 molecule−1 s−1; Table 1). Therefore, the higher rate constant for oxidation by HO2 in comparison to NO favours the RO2+HO2 pathway.

The ratio, , combines the difference in rate constants together with differences in the ratio of oxidant concentrations, and ranges from 100 to 104 over most continental regions, but is as low as 10−2 over remote marine environments, such as the Pacific Ocean and South Atlantic Ocean (Fig. 11d). Hence, the net effect of differences in oxidant concentrations and rate constants is to favour peroxy radical removal via the NO oxidative pathway (Figs. 10a; 11d). This preference for the NO radical pathway is enhanced even further by considering the likelihood of RO2 being co-located with NO. RO2 is a second-generation oxidation product of VOCANT∕BB, which is released by anthropogenic and biomass burning sources. NO emissions are predominantly emitted from anthropogenic and biomass burning sources. Therefore, peroxy radicals are very likely to be formed in NO-rich environments, further favouring the probability of entering the RO2+NO pathway. Furthermore, adoption of naphthalene reactivity for VOCANT∕BB, which is still relatively high, prevents transport away from high-NO regions. Overall, peroxy radicals preferentially react via the NO pathway due to relatively higher NO concentrations than HO2, despite the HO2 pathway having a higher rate constant.

5.1.3 Production of SOA from new reaction intermediate, RO2