the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Global atmospheric hydrogen chemistry and source-sink budget equilibrium simulation with the EMAC v2.55 model

Nic Surawski

Benedikt Steil

Christoph Brühl

Sergey Gromov

Klaus Klingmüller

Anna Martin

Andrea Pozzer

Jos Lelieveld

In this study, we use an earth system model with detailed atmospheric chemistry (EMAC v2.55.2) to undertake simulations of hydrogen (H2) atmospheric dynamics. Extensive global equilibrium simulations were performed with a horizontal resolution of 1.9°. The results of this simulation are compared with observational data from 56 stations in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Global Monitoring Laboratory (GML) Carbon Cycle Cooperative Global Air Sampling Network. We introduced H2 sources and sinks, the latter inclusive of a soil uptake scheme, that accounts for bacterial consumption. The model thus accounts for detailed H2 and methane (CH4) flux boundary conditions. Results from the EMAC model are accurate and predict the magnitude, amplitude and interhemispheric seasonality of the annual H2 cycle at most observational stations. Time series comparison of EMAC and observational data produces Pearson correlation coefficients (r) in excess of 0.9 at eight remote stations located in polar regions and on high mid-latitude islands. A further 23 stations yielded correlation coefficients between 0.7–0.9, predominantly located in remote marine stations across all latitudes and also in polar regions. The quality of model predictions (r<0.5, 9 stations) is reduced in anthropogenically highly polluted stations in east Asia and the Mediterranean region and stations impacted by peat fire emissions in Indonesia, as local and incidental emissions are difficult to capture. Our H2 budget corroborates bottom-up estimates in the literature in terms of source and sink strengths and overall atmospheric burden. By simulating hydroxyl radicals (OH) in the atmosphere leading to a CH4 lifetime in agreement with observationally constrained estimates, we show that the EMAC model is a capable tool for undertaking high accuracy simulation of H2 at global scale. Future research applications could target the impact of potentially significant natural and anthropogenic H2 sources on air quality and climate, reducing uncertainties in the H2 soil sink and impacts of H2 release on the future oxidising capacity of the atmosphere.

- Article

(5594 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1333 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

H2 represents an essential energy vector for 2050 net zero decarbonisation targets to be met. Current demand for H2 equates to approximately 95 Mt per year with existing uses in the refining industry, as well as the chemical industry for production of ammonia, methanol and other chemicals (Hydrogen Council, 2021; International Energy Agency, 2023). H2 is also used in the direct reduction of iron along with smaller uses in electronics, glassmaking and metal processing (International Energy Agency, 2023). With increased governmental, financial and policy support, demand for H2 is forecasted to rise to between 430–690 Mt by 2050 (Hydrogen Council, 2021; International Energy Agency, 2023). Achieving this projected level of hydrogen demand can support clean energy use in: (1) hard to abate sectors such as long-haul trucking, shipping and aviation, (2) sectors that require a clean molecule as a chemical feedstock such as for co-firing of natural gas turbines or industrial processes such as steel manufacturing, (3) sectors that require a source of low carbon heat such as for cement and aluminium production or for buildings (Hydrogen Council, 2021; International Energy Agency, 2023). Use of H2 offers a lot of potential for securing decarbonisation outcomes, provided clean production pathways are prioritised (Hydrogen Council, 2021; International Energy Agency, 2023), carbon capture and storage technologies (if required) work efficiently and at scale (International Energy Agency, 2020), and leakage rates in the H2 value chain are minimised with sound engineering design (Esquivel-Elizondo et al., 2023; Fan et al., 2022).

Despite these potential advantages for decarbonisation, H2 has well-documented climate impacts following its release into the atmosphere which represents an important environmental challenge. In terms of climate impacts, H2 is an indirect greenhouse gas that leads to increases in radiatively active species by increasing (1) CH4 lifetime due to H2 competing for the OH sink (2) tropospheric ozone production due to a chain of reactions initiated by the H atom and (3) stratospheric water vapour that enhances radiative forcing (Derwent et al., 2006; Paulot et al., 2021; Ocko and Hamburg, 2022; Warwick et al., 2022, 2023). Since H2 release affects the oxidising capacity of the atmosphere, it may also lead to changes in the production of sulphate, nitrate and secondary organic aerosols (Sand et al., 2023). Arising from these modelled results, coupled chemistry-climate modelling has a vital role to play before future H2 infrastructure is installed to ensure that projected increases in H2 utilisation do not lead to significant adverse consequences for the earth’s atmosphere, air quality and climate.

Simulation of H2 atmospheric chemistry impacts has attracted significant research attention both in the past few decades (Hauglustaine and Ehhalt, 2002; Schultz et al., 2003; Tromp et al., 2003; Warwick et al., 2004) and at present (Derwent et al., 2020; Paulot et al., 2021, 2024; Warwick et al., 2023) given the likelihood that demand for H2 usage will grow and potential environmental impacts still require a solution. Previous attempts at simulating hydrogen mixing ratios with coupled chemistry-climate modelling have met variable levels of success at global scale. In this article, we show that the EMAC model is a highly capable tool for capturing (1) the magnitude, amplitude and seasonality of the annual H2 cycle and (2) the meridional gradients in H2 mixing ratios. These findings support the conclusion that the EMAC model consistently represents the interplay between the dominating soil sink (i.e. 75 % of all sink terms) and atmospheric photochemical production (i.e. 63 % of all source terms) which is by far the largest source term for H2 (Table 2).

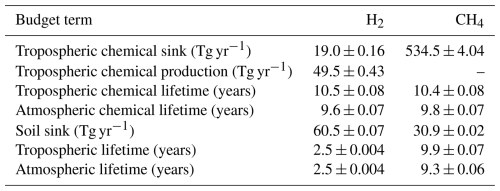

Table 1Chemical budgets and lifetimes for H2 and CH4. Uncertainties are calculated as the standard deviation of multi-year annual global means. Note that lifetimes are always calculated with respect to global burden (Prather et al., 2012; SPARC, 2013).

In this work, we employ the EMAC model which couples the 5th generation European Centre Hamburg General Circulation Model (ECHAM5; Roeckner et al., 2003, 2004, 2006) to the Modular Earth Submodel System (MESSy) (Jöckel et al., 2006, 2010). Simulations were performed with T63 spectral resolution which produces a spatial resolution of 1.9° (approximately 180–190 km). Simulations were performed with 90 levels up to 80 km above the earth’s surface, encompassing both the lower and middle atmosphere. Chemical reactions in the atmosphere were modelled with version 1 of the Mainz Isoprene Mechanism (MIM1; Pöschl et al., 2000; Jöckel et al., 2006). The model experiment is representative of the present-day (i.e. the year 2020) and uses meteorology for the years 2006–2023, with the first four years used as spin-up time. Flux boundary conditions were employed for both CH4 and H2 to overcome issues with the introduction of artificial sources and sinks arising from using Dirichlet boundary conditions with a prescribed mixing ratio at the lower boundary of the atmosphere. H2 and CH4 are chemically coupled and have nearly the same chemical lifetime (Table 1). Both compete for the OH radical as a chemical sink, with OH being by far the dominant sink for atmospheric CH4 (Saunois et al., 2025; see Sect. 4.1 below). Furthermore, atmospheric oxidation of CH4 is the largest source for H2 (Ehhalt and Rohrer, 2009). To adequately simulate such a coupled system, the EMAC model uses flux boundary conditions for sources and sinks of both species. To reach a steady-state for the control simulation, the initial conditions for CH4 and H2 were obtained from a 15 years long simulation, covering the period 1990–2005. CH4 was simulated based on the work of Zimmermann et al. (2020), in which emissions of CH4 and deposition are represented based on the year 2020. Integration of the equations in the simulation uses a time-step of 450 s, and, due to the relatively long lifetime of H2, precluding diel variability, instantaneous values are outputted every day.

2.1 Emissions

In this work, the goal is to undertake an equilibrium simulation that reaches steady-state mixing ratios representative of present day atmospheric conditions. Therefore, emissions are based on the year 2020, or the closest year prior to 2020, and are repeated for each year which removes any interannual variability. Due to increasing emissions and its long lifetime CH4 is not in a steady state. Therefore an equilibrium simulation is not fully representative of the atmospheric state in 2020.

For the long-lived tracer CH4, the a posteriori emissions and the best combination of the rising-CH4 scenario of Zimmermann et al. (2020) have been applied. In this work, Zimmermann et al. (2020) show that the EMAC model has been efficient in simulating interactive CH4 mixing ratios over the last two decades. Therein, the model results compare quite well with NOAA and The Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE) stations and measurements from CARIBIC (Civil Aircraft for the Regular Investigation of the Atmosphere Based on an Instrument Container) flight observations (Brenninkmeijer et al., 2007). Twelve emission categories are considered here, namely, wetlands other than bogs (SWA), animals (ANI), landfills (LAN), rice paddies (RIC), gas production (GAS), shale gas drilling (SHA), bogs (BOG), coal mining (COA), including minor natural sources from oceans, other anthropogenic sources, volcanoes, oil production and offshore traffic, oil-related emissions (OIL), biomass burning (BIB), termites (TER), and biofuel combustion (BFC). Only emissions from bogs, rice fields, wetlands other than bogs, and biomass burning are subject to seasonal variability. Most of the emissions are based on the emission fields of the Global Atmospheric Methane Synthesis (GAMeS) in which processes with similar isotopic characteristics are aggregated into one group (Houweling et al., 1999). For biomass burning, the GAMeS dataset is replaced by the GFEDv4s (Randerson et al., 2017) and is vertically distributed according to a profile suggested in the EDGAR database (Pozzer et al., 2009). The GFEDv4s biomass burning statistics include agricultural waste burning events. A total amount of 601.1 Tg yr−1 of CH4 is emitted in the model and detailed emissions for each sector can be found in Tables 1 and 3 of Zimmermann et al. (2020), which also describe in detail the emission optimisation process.

H2 emissions were taken from the RETRO dataset (Lamarque et al., 2010), which was chosen due to its completeness. As for the other sources, we repeated the emissions based on one single year, namely the year 2000. The RETRO database covers the period 1960–2000, and the last year was taken as representative of 2020 emissions, motivated by the stagnation of H2 emissions in the past few decades (Paulot et al., 2021). A global value of 14.3 Tg yr−1 for anthropogenic emissions is obtained from the RETRO database, as well as 4.8 Tg yr−1 from soil emissions. Biomass burning emissions were obtained from the GFED (Global Fire Emissions Database) database (Giglio et al., 2013), and accounted for 8.35 Tg yr−1. As the RETRO oceanic emissions are outside the range of emissions suggested by the literature (Paulot et al., 2024), these emissions were upscaled to 3 Tg yr−1 so to be within the suggested range (i.e. between 3–6 Tg yr−1). Both the RETRO and GFED databases provide direct estimates of H2 emissions without relying upon an assumed H emissions ratio.

For non-GHGs, different emissions were adopted. Anthropogenic sources of short-lived gases are based on CAMS-GLOB-ANTv4.2 and CAMS-GLOB-AIRv1.1 (Granier et al., 2019), and the emissions are estimated with reduction due to lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic (Reifenberg et al., 2022). The reduction in the mixing ratio of the OH radical is below 4 % for most of the atmosphere, with the exception of the uppermost troposphere and tropopause region, which is due to reduced flight activity. The small impact on OH is foremost confined to mid-latitudes of the northern hemisphere. Biomass burning emissions are calculated online on a daily basis and rely on dry matter burned from observations and fire type (Kaiser et al., 2012). The emission factors for different tracers and fire types are taken from Andreae (2019) and Akagi et al. (2011). The simulation uses a climatology of the aerosol wet surface density to calculate heterogeneous reactions. It is based on the CMIP5 (Climate Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5) emissions climatology for the years 1996–2005 low S scenario (Righi et al., 2013). The aerosol distribution for radiative forcing calculation is the Tanre climatology (Jöckel et al., 2006). The biogenic emissions of organic species have been compiled following Guenther et al. (1995) and are prescribed in the model in an offline manner (Kerkweg et al., 2006), with the exception of biogenic isoprene and terpenes, for which the emissions are calculated online (Kerkweg et al., 2006).

2.2 Soil sink implementation

We estimate the soil sink using a two-layer soil model (Yonemura et al., 2000; Ehhalt and Rohrer, 2013a; Paulot et al., 2021). H2 is assumed to diffuse through a dry top layer of soil with no bacterial activity (layer I), which may be covered by an equally inactive layer of snow. In a second layer below the top layer (layer II), the rate of H2 removal by high-affinity hydrogen-oxidising bacteria (Paulot et al., 2021) depends on both soil temperature and moisture. The resulting deposition rate is parameterised by:

The first two terms in parenthesis in the denominator of Eq. (1) represent diffusion through the inactive soil layer and the snow layer of thickness δ and δsnow, respectively. The diffusivity of H2 in soil is given by Millington and Quirk (1959):

which depends on the volumetric soil water fraction θw and the volumetric soil pore fraction (i.e. porosity) θp. The diffusivity of H2 in snow is given by:

while the diffusivity of H2 in air is given by:

where the diffusivity of H2 in air depends on the air temperature T in °C and the air pressure p in hPa.

The third term in parenthesis in the denominator of Eq. (1) represents H2 removal in the lower, active layer. The temperature dependence is given by Ehhalt and Rohrer (2011):

where T is the soil temperature in °C.

The soil moisture dependence in terms of the water saturation for eolian sand is given by Ehhalt and Rohrer (2011):

where is the minimum level of water saturation required for microbial activity. For loess loam the soil moisture dependency is given by Ehhalt and Rohrer (2011):

where . For a mixture of eolian sand and loess loam we use the weighted mean given by:

where φsand is the sand fraction of the soil. The resolution-dependent constant A represents bacterial activity and is adjusted to yield a global mean deposition velocity of 0.033 cm s−1 over land during 2012 to 2015 (Yashiro et al., 2011). Using the 0.25° grid spacing of the ERA5 input data, we obtain A=10.9.

The thickness of the upper soil layer without hydrogenase (i.e. an enzyme in prokaryotes such as bacteria that consume H2) activity is parametrised by:

in sandy loam and

in loam. Both δs and δl are expressed in cm. For a mixture of sandy loam and loam with sand fraction φsand we use the weighted mean to calculate the soil layer thickness via:

The soil water content in the top, dry layer (i.e. θwI) is assumed to be the threshold moisture content below which the bacterial activity vanishes, i.e. there is no H2 uptake in this layer, and is given by:

where is the threshold moisture content for eolian sand and for loess loam.

Accordingly, the remaining water within the top 10 cm of soil is between depth δ and 10 cm, resulting in a soil water content for the second layer (i.e. θwII) of:

We evaluated Eq. (1) using monthly reanalysis data for soil moisture, soil temperature, air pressure, snow depth and snow density with a 0.25° grid spacing from the ERA5 dataset provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) (Hersbach et al., 2020, 2023). The mean soil moisture and soil temperature for the top 10 cm soil layer was obtained by linearly interpolating the ERA5 soil level data. The volumetric soil water content was then uniformly reduced by 6 % (Paulot et al., 2021). Static soil porosity and sand fraction maps with 0.25° grid spacing were obtained from the Land Data Assimilation System (LDAS) (Rodell et al., 2004; GLDAS, 2024).

The global distribution of the H2 deposition velocity averaged over the 2012 to 2021 period resembles the maps presented by Paulot et al. (2021), but with more pronounced extrema (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). The zonal mean of the H2 deposition velocity over land also falls within the range of results reported by Paulot et al. (2021). However, the local minimum around 20° N, due to the Sahara, and the maximum around 10° N, where the transition to more humid regions favours soil uptake, are more distinct in this study than in most of those shown by Paulot et al. (2021) (Fig. S2). Thanks to extensive observational records of atmospheric hydrogen concentrations at stations around the world, it is possible to carry out detailed validation of hydrogen deposition based on the resulting concentrations. This method, presented in the following sections, is more informative than local deposition analysis because it is less susceptible to significant variations in surface conditions and is based on a much larger database.

2.3 Observations

EMAC simulations are compared with observational data from 56 stations (with more than 12 monthly values) that form part of the NOAA GML Carbon Cycle Cooperative Global Air Sampling Network (Petron et al., 2024). Data gaps exist at some stations due to the application of quality control procedures, as well as missing data due to impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. For comparison with the results of the EMAC equilibrium simulation, the observed monthly values have been detrended by subtracting the trend obtained by a sixth order harmonic regression with a linear trend term, while keeping the mid-year values for 2020 fixed.

Figure 1 presents a global map of modelled annual mean H2 mixing ratios as well as the location of observational stations that we use for model inter-comparison purposes. This global map shows the inter-hemispheric gradient for this molecule whereby H2 mixing ratios are higher in the southern hemisphere compared to the northern hemisphere. This global map also shows the influence of pollution hotspots in Asia, and the influence of biomass burning emissions in central Africa and peat fire emissions in southeast Asia.

Figure 1Global map of H2 mixing ratios and the location of observational stations. Model data is averaged over the years 2010–2023 (inclusive) which is representative of the year 2020 for a steady-state simulation, while observational data uses mid-2020 values from a detrending fit using a sixth order harmonic regression technique.

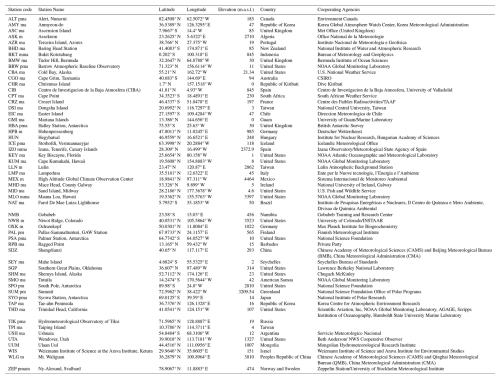

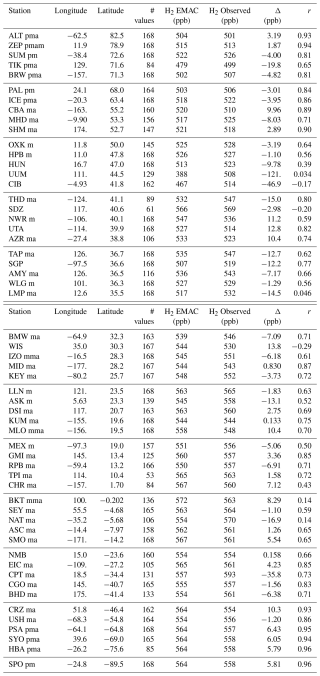

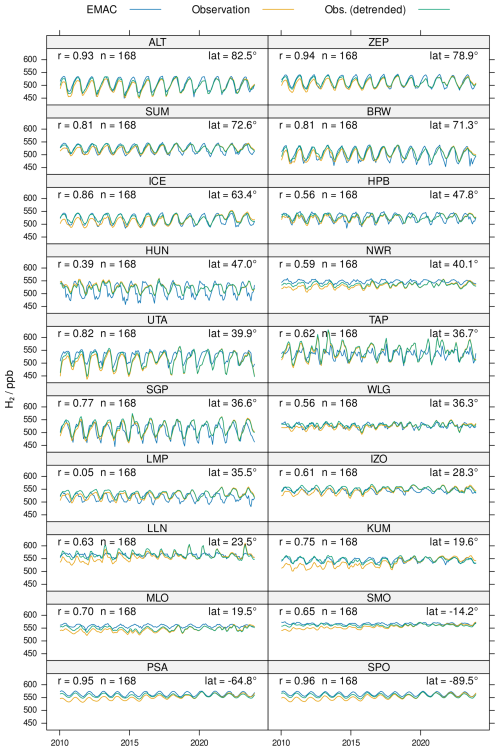

We show time series data for model comparisons with observational data (without gaps in monthly data) from 20 observational stations in Fig. 2. Further comparisons with observational data from another 36 observational stations (with data gaps) are shown in Figs. B1 and B2. 38 of the 56 stations have marine characteristics (Table A1 and Fig. 1), i.e. are located coastally or on islands. 11 stations can be described as polar (latitude ), and 14 stations are positioned on mountains (i.e. a single station might have several characteristics). These stations usually measure remote, often marine air masses or free tropospheric concentrations. Just 8 stations Hungary (HUN), Mongolia (UUM) , CIBA (CIB, northern central Spain), Shangdianzi (SDZ, China), Wendover (UTA, Utah), Southern Great Plane (SGP, Oklahoma), Israel (WIS), and Gobabeb (NMB, Namibia) fall in none of these previous categories. Inner continental non-mountain stations are sparse, with none in South America and Australia. The two continental stations in Africa (ASK, and NMB) are located in the desert. There are also no monitoring stations in Central Asia. The three Mediterranean stations (CIB, LMP, and WIS) and the continental Chinese (SDZ) and Mongolian (UUM) stations are located in or close to areas with high air pollution levels (Lelieveld et al., 2002; Silver et al., 2025). The Bukit station (BKT, Indonesia) is also regularly impacted by biomass burning and peat fires (Yokelson et al., 2022).

Across these 56 observational stations, the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) exceeds 0.9 for eight remote stations located either in the Arctic or Antarctic regions and on islands at high mid-latitudes. In such cases, the annual cycle of H2 is modelled excellently in terms of magnitude, amplitude and seasonality. In contrast, nine stations produce correlation coefficients below 0.5. The three stations in the Mediterranean region CIB (−0.17), LMP (0.05) and WIS (−0.29) and the Chinese and the Mongolian stations SDZ (−0.2) and UUM (0.03) show correlation coefficients close to zero or even negative. Negative r values suggest that the EMAC model does not correctly capture the phasing of the annual H2 cycle which results in pronounced phase mismatches or anti-correlation in Table and Figs. 2, B1, and B2. These stations are located in regions known for high levels of air pollution. The two tropical coastal stations BKT (0.14) and the Natal station in Brazil (NAT, 0.14) do show rather low r values compared to other tropical stations. They are impacted by biomass burning (i.e. NAT) and peat fire emissions (i.e. BKT). The comparison at the Hungarian station (HUN, 0.39) shows a considerably lower r value compared to the other two central European stations Hohenpeissenberg (HPB, 0.56) and Ochsenkopf (OXK, 0.64). HPB and OXK are mountain stations less susceptible to local mismatches in H2 soil deposition, as can be seen from the much better matching of model amplitude and phasing with measurements. The Christmas Island station (CHR, 0.43) is the only very remote tropical island station, which has a considerably low r value. At this station, the observational time series is relatively short with hardly any annual cycle. Another 23 stations have correlation coefficients between 0.7–0.9 which demonstrate very good agreement between model and observational data. A number of these stations are located in the mid-latitudes either in the northern or southern hemisphere. The remaining 16 stations produce correlation coefficients between 0.5–0.7 mostly in either remote tropical or mid-latitude regions. Especially the Antarctic stations show an upward trend for atmospheric H2. The model with its emissions and soil sink repeating the year 2020, cannot capture this feature. This trend coincides with further increasing atmospheric CH4 concentrations after 2010 following its hiatus of the previous decade (Lan et al., 2026). Table 2 shows that oxidation of atmospheric CH4 is the largest source term for H2 (Ehhalt and Rohrer, 2009). To investigate this further in the future, a model simulation with flux boundary conditions for H2 and CH4 in transient mode is needed. Overall, the results are very promising and demonstrate the ability of the EMAC model to predict H2 mixing ratios accurately in most regions of the earth. To provide a visual overview of these results, Fig. 3 provides a global map of Pearson correlation coefficients for comparison of EMAC and observational data.

Figure 2Time series comparison of observational and EMAC model data for H2. Results are presented for 20 stations without any gap in monthly data. The sample size for observational data is denoted by n, while r is the Pearson correlation coefficient. Latitudes are denoted by lat.

Figure 3Pearson correlation coefficient for the intercomparison between EMAC and observational data for H2. Model data is compared with detrended observational data for the years 2010–2023 (inclusive) to perform this calculation.

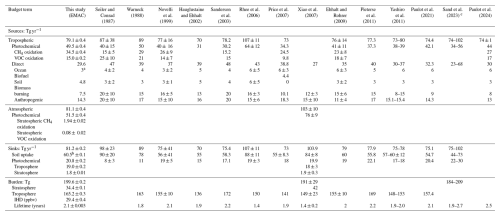

Table 2Tabulation of the H2 budget from this study and from literature estimates. Uncertainties are calculated as the standard deviation of multi-year annual means.

a Up-scaled from 0.5 to 3 Tg yr−1 to match literature recommendations (Paulot et al., 2021); b the dry deposition velocity of H2 (Paulot et al., 2021) has been reduced by 6 % (from the continental

global mean of 0.035 to 0.033 cms−1) to improve simulated H2 especially in polar latitudes. c Multi-model results are presented as a range. VOC = volatile organic compound. IHD = interhemispheric difference.

We also present a plot of the meridional gradient in H2 in Fig. 4. Overall, meridional gradients in H2 are captured very well by the EMAC model, notably for stations located in the southern hemisphere, likely because many represent the background atmosphere, whereas many stations in the northern hemisphere are affected by local influences. The model correctly predicts higher H2 mixing ratios in the southern hemisphere even though the majority of H2 sources are present in the northern hemisphere. The predicted interhemispheric gradient in H2 presented here is correct by virtue of the greater soil sink that is present in the northern hemisphere arising from its larger land area (Ehhalt and Rohrer, 2009). Most of the discrepancies between the observed and predicted H2 mixing ratios exist for a small number of stations within the northern hemisphere mid-latitudes (between 30–60° N) and in the tropics, presumably influenced by local source variability that is insufficiently resolved by our global model. The coverage of many continental land masses by the observational stations is sparse. For South America, Australia, Africa, Central Asia, Siberia and India there are almost no measurements available. This is a problem, especially in validating the soil sink, which can be considered the most uncertain part of the H2 budget (Paulot et al., 2021).

Figure 4Meridional gradients in H2 for EMAC predictions and observational data where stations had more than 12 monthly values. The solid lines were obtained by locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS; smoothing parameter , locally linear). Negative latitudes represent south and positive latitudes represent north of the equator. Data are shown for stations with more than 12 monthly values.

For further results, we refer the reader to Appendix B which provides further graphs and tabulated summaries of model performance.

4.1 Model comparison with observational data

A key feature of the results (Figs. 2, B1, and B2) is the ability of the EMAC model to realistically predict the magnitude, amplitude and seasonality of the annual H2 cycle at most stations, in unison with that from CH4 (Zimmermann et al., 2020), with both compounds being modelled with flux boundary conditions and interactive sinks. Promising results are obtained especially for stations that experience remote air masses, for example, in mostly polar regions, which are particularly sensitive to atmospheric transport and chemistry dynamics. The EMAC model results are also quite promising in a range of mid-latitude stations both in the northern and southern hemisphere. In contrast, there are some regions of the globe (Fig. 3) where results are not as promising. For example, the EMAC model predictions are less accurate in the highly anthropogenically polluted Mediterranean region, near the Amazonian region which is impacted by biomass burning emissions, and southeast Asia which is impacted by peat fire emissions. Due to the coarse spatial resolution of 180–190 km and limited information about local and incidental sources, the variability of mixing ratios in these regions is more challenging to capture. This is especially the case for some coastal stations (e.g. NAT, BKT) where the model is limited due to resolution in accurately representing the mixing of marine and continental air. Also the deviations in China and Mongolia (SDZ, UUM) can be partly attributed to a resolution effect. Both stations are located close to strong horizontal gradients in H2 mixing ratios. The vertical resolution of the lowermost model layers (i.e. thicknesses of 66, 166 and 319 m from the surface upwards) and the representation of the orography influence the comparison. It is important to consider the measurement height relative to the surface and the geographic prominence of the stations. For example, the modelled amplitude of the annual H2 cycle can be reduced by up to 40 % between the surface and the next model layer for continental stations due to the importance of the soil sink, whereas the H2 mixing ratios increase with height driven by the strong atmospheric chemical H2 production. In addition, an interesting model-measurement discrepancy occurs at the Weizmann Institute of Science (WIS) station near the northern Red Sea, where unaccounted for alkane emissions have been attributed to natural seepage from deep water sources (Bourtsoukidis et al., 2020), possibly accompanied by H2 emissions. Overall, the EMAC model performs favourably at a global scale for simulating H2 mixing ratios. Comparison with model output from Yashiro et al. (2011) shows that while the EMAC model produces correlation coefficients in excess of 0.7 for over half of the observational stations, the CHASER chemistry-climate model achieves the same result for only one quarter of all observational stations. The annual mean H2 mixing ratios are well captured by the EMAC model (Table and Fig. 4), with the exception of CIB (), UUM (r=0.03), and the coastal station Cape Town (CPT) despite its high Pearson correlation coefficient (r=0.73). As mentioned above, the H2 observational stations do not represent the inner region of continents well. Especially, the small number (i.e. UTA, SGP, UUM) of remote non-mountain, non-hyperarid stations, placed away from highly anthropogenically influenced regions limits its usage in looking in more detail on the parametrisation of the soil sink. At Wendover (UTA, Utah, arid cold climate, r=0.82) and the Southern Great Planes (SGP, Oklahoma, humid subtropical climate, r=0.77), shown in Fig. 2, the model performs well by realistically representing the magnitude, amplitude and seasonality of the observations, indicating that the soil sink parametrisation of H2 is realistic in those regions. The poor results at the Mongolian station (UUM, arid cold climate, r=0.03), Fig. B1, might be partly attributed to a resolution effect (see above).

To successfully simulate H2 mixing ratios in the atmosphere, a model needs to correctly resolve the complex interplay between meteorology and chemistry. In terms of chemistry, having the oxidising capacity of the atmosphere represented correctly is a key consideration (Prather and Zhu, 2024). It is largely controlled by the concentration of OH radicals in the troposphere (Lelieveld et al., 2016) and determines the atmospheric lifetime of numerous species including CH4. The total CH4 sink is largely dominated by its reaction with OH (see Saunois et al., 2025 for a review). In this sense, CH4 lifetime is a measure for the total oxidative capacity of the atmosphere. Observational estimates derived from methyl chloroform (CH3CCl3) measurements lead to a total atmospheric CH4 lifetime of 9.1 ± 0.9 years (Prather et al., 2012). Our estimate of 9.3 ± 0.06 years (Table 1) compares well, and is only marginally higher than the range indicated by Prather et al. (2012). This also holds for the global tropospheric chemical CH4 sink. The supporting information of Prather et al. (2012) states that for the tropospheric CH4 lifetime based on the reaction with OH (i.e. 11.2 ± 1.3 years) and for the lifetime of CH4 based on the reaction with tropospheric chlorine (i.e. 200 ± 100 years) yields a combined tropospheric chemical lifetime of 10.6 ± 1.2 years for CH4. This value compares quite well with our estimate of 10.4 years (Table 1). Model intercomparisons performed by Nicely et al. (2020) suggests that many chemistry models underestimate CH4 lifetime due to simulating an atmosphere that is overly enriched in OH radicals. Recently, work by Yang et al. (2025) concurs that several atmospheric chemistry models over-predict OH mixing ratios which has implications for CH4 and H2 lifetimes. The multi-model estimate from CMIP6 (Coupled-Model Intercomparison Project 6; Collins et al., 2017) and CCMI (Chemistry Climate Model Initiative; Plummer et al., 2021) models used by the Global Carbon Project community for the bottom-up estimates of CH4 sources yields a total CH4 lifetime of 8.2 years with a range of 6.8–9.7 years (Saunois et al., 2025). It also shows a large spread, which propagates into increased uncertainties for the derivation of emission budgets. We believe that the EMAC model is realistically capturing the total oxidising capacity of the atmosphere which helps to facilitate high-accuracy prediction of H2 and CH4 dynamics.

4.2 Budget and lifetimes

In the atmosphere, CH4 and H2 are tracers strongly connected with similar chemical fates. Table 1 shows that CH4 and H2 have nearly identical chemical lifetimes both in the troposphere and atmosphere. Furthermore the total sources of H2 and CH4, corrected for molecular masses, are very comparable. The biggest difference between these two compounds stems from hydrogen's much larger soil sink which reduces its tropospheric lifetime by approximately a factor of four compared to CH4.

In Table 2, we compare our H2 budget derived from EMAC model output with other estimates from the literature. We find that our H2 budget agrees favourably with bottom-up literature estimates that rely on a combination of emission datasets and model calculations of turnovers and loss rates, but differs from top-down estimates relying on either inverse modelling (Xiao et al., 2007) or analysis of the 2H (i.e. deuterium) budget (Rhee et al., 2006). Our overall budgeting of sources and sinks agrees very well with bottom-up estimates. In addition, our tropospheric H2 lifetime is in very good agreement with bottom-up estimates. The tropospheric burden is in the upper range of model estimates. Note, that the upper boundary of the tropospheric range is often not clearly defined in the literature, with different definitions e.g. 100 hPa, World Meteorological Organization (WMO), or a climatological tropopause being used. In this study the WMO tropopause definition is used based on a dynamic tropopause in high latitudes and lapse rate being used at low latitudes. The photochemical production is in between the range for bottom-up and top-down estimates (Paulot et al., 2021). These findings suggest that the EMAC model simulates a realistic atmospheric oxidation capacity which is a critical requirement for predicting H2 mixing ratios well.

Recent work by the United States Geological Survey (Ellis and Gelman, 2024) has developed a simple, zero-dimensional mass balance model coupled with Monte Carlo uncertainty analysis to explore global potential for geological (or gold) H2 production in the earth's crust. Median modelled estimates of the subsurface H2 resource are approximately 5.6 × 106 Mt. Ellis and Gelman (2024) estimate that global geological H2 resources cause an additional global flux of 24 Tg yr−1 from the subsurface to the atmosphere. This is speculative and would add unaccounted H2 emissions almost of the strength of the current non-photochemical sources. Current knowledge concerning the budget of atmospheric H2 does not exclude the existence of a large geological H2 reservoir, and further emphasises the importance of dry deposition for the global atmospheric H2 budget.

4.3 Suggestions for future applications

Future research efforts in modelling H2 atmospheric chemistry could build on the current work in three key ways. Firstly, scenarios could be constructed to explore what role geological H2 (i.e. gold H2) holds for future atmospheric chemistry. If economically extractable reserves of gold H2 are found, future utilisation of H2 would increase well beyond current projections (Hand, 2023; Truche et al., 2024; Ellis and Gelman, 2024). It would therefore be critical to assess the atmospheric chemistry implications of vastly increased H2 usage. Secondly, it will be critical to assess what impact H2 use has on the future oxidising capacity of the atmosphere. Clean H2 use will be associated with significant reductions in the co-emission of criteria pollutants (Galimova et al., 2022) which will influence the formation of atmospheric oxidants such as ozone and OH radicals that constrain CH4 and H2 lifetimes (Archibald et al., 2011; Brasseur et al., 1998; Ganzeveld et al., 2010). Thirdly, the H2 budget is dominated by the land sink (Tables 1 and 2) and future research efforts could help to constrain the important role played by a number of soil properties (e.g. porosity, soil moisture, temperature, and organic carbon content) on terrestrial H2 uptake (Ehhalt and Rohrer, 2011, 2013a; Paulot et al., 2021; Smith-Downey et al., 2006). The production of H2 by enzymes in soil (i.e. hydrogenases) could also be considered in a depth-resolved manner as knowledge of the underlying processes improves (Ehhalt and Rohrer, 2013b). Recent coupling of the JSBACH vegetation model to EMAC by Martin et al. (2024) has developed a potential model tool for undertaking on-line H2 land sink calculations.

In this study, we have successfully extended and used the EMAC model to undertake simulations of H2 atmospheric dynamics, constrained by flux boundary conditions for both H2 and CH4. Comparing the EMAC model output with observational data at 56 stations from the NOAA GML Carbon Cycle Cooperative Global Air Sampling Network generally indicates very good agreement at global scale. Excellent results are achieved at remote observational stations and for stations measuring remote and free tropospheric air, suggesting that atmospheric source, sink and transport processes are accurately represented, while model performance is degraded at stations impacted by nearby pollution sources. Our H2 budget is also in good agreement with bottom-up estimates in the literature. We find that the EMAC model simulates the CH4 chemical lifetime in excellent agreement with observational estimates, which suggests the model calculates OH radical mixing ratios in a representative manner. The H2 soil sink, based on a two-layer soil model (Yonemura et al., 2000; Ehhalt and Rohrer, 2013a; Paulot et al., 2021), in combination with monthly ERA5 reanalysis data for soil related parameters has been successfully used by the EMAC model. We conclude that atmosphere chemistry models with such features, capturing the most dominant terms of the atmospheric H2 budget, should be able to generally simulate station observations of atmospheric hydrogen. This gives confidence that scenario simulations regarding the future H2 economy will provide reliable estimates of its atmospheric impact.

Figure B1 Time series comparison of observational and EMAC model data for H2. Latitudes are denoted by lat. [Other stations part 1].

Figure B2 Time series comparison of observational and EMAC model data for H2. Latitudes are denoted by lat. [Other stations part 2].

Figure B3Pearson correlation coefficient between EMAC CH4 mixing ratios and observational data. Model data is compared with detrended observational data for the years 2010–2023 (inclusive) to perform these calculations. For a more extensive comparison see Zimmermann et al. (2020).

The Modular Earth Submodel System (MESSy) is in continuous development and is used by a consortium of institutions. Source code access and usage is licensed to all affiliates of institutions which are members of the MESSy Consortium. Institutions can become a member of the MESSy Consortium by signing the MESSy Memorandum of Understanding. The MESSy Consortium website (http://www.messy-interface.org, last access: 22 January 2026) provides further information regarding access to the model. The exact version of the EMAC v2.55.2 source code and simulation set-ups used to produce the results used in this paper is archived on the Zenodo repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15211346 (The MESSy Consortium, 2025).

Regarding data availability, access to the NOAA GML Carbon Cycle Cooperative Global Air Sampling Network data is available at https://doi.org/10.15138/WP0W-EZ08 (Petron et al., 2024), the ERA5 reanalysis data is available at https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47 (Hersbach et al., 2023), and the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED) v4.1 data is available at https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1293 (Randerson et al., 2017). The monthly H2 deposition velocity at 0.25° resolution is available from the Edmond Open Research Data Repository of the Max Planck Society (https://doi.org/10.17617/3.PLYVTZ, Klingmüller, 2025).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-19-911-2026-supplement.

JL managed the project with contributions from AP. BS led the delivery of model simulations with contributions from AP, KK, SG, CB and NS. KK led the delivery of soil sink modelling with contributions from BS and AM. CB led the collation of observational data and its quality control with contributions from BS. SG led the delivery of chemical tagging with contributions from BS. NS wrote the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors. All authors met to discuss the results and contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Geoscientific Model Development. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

NS acknowledges funding support from the CSIRO International Hydrogen Research Fellowship scheme and the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology at UTS to undertake a sabbatical at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz. All simulations were performed with the Levante High Performance Computing System (https://www.dkrz.de/en/systems/hpc/hlre-4-levante, last access: 22 January 2026) hosted by Deutsches Klimarechenzentrum GmbH.

This research has been supported by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (grant no. PRO23-18036). The research of Anna Martin has been supported by the Max Planck Graduate Center with the Johannes Gutenberg University (Mainz).

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the Max Planck Society.

This paper was edited by Fiona O'Connor and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Akagi, S. K., Yokelson, R. J., Wiedinmyer, C., Alvarado, M. J., Reid, J. S., Karl, T., Crounse, J. D., and Wennberg, P. O.: Emission factors for open and domestic biomass burning for use in atmospheric models, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 11, 4039–4072, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-4039-2011, 2011. a

Andreae, M. O.: Emission of trace gases and aerosols from biomass burning – an updated assessment, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 19, 8523–8546, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-8523-2019, 2019. a

Archibald, A. T., Levine, J. G., Abraham, N. L., Cooke, M. C., Edwards, P. M., Heard, D. E., Jenkin, M. E., Karunaharan, A., Pike, R. C., Monks, P. S. Shallcross, D. E., Telford, P. J., Whalley, L. K., and Pyle, J. A.: Impacts of HOx regeneration and recycling in the oxidation of isoprene: Consequences for the composition of past, present and future atmospheres, Geophysical Research Letters, 38, L05804, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010gl046520, 2011. a

Bourtsoukidis, E., Pozzer, A., Sattler, T., Matthaios, V. N., Ernle, L., Edtbauer, A., Fischer, H., Könemann, T., Osipov, S., Paris, J.-D., Pfannerstill, E. Y., Stönner, C., Tadic, I., Walter, D., Wang, N., Lelieveld, J., and Williams, J.: The Red Sea Deep Water is a potent source of atmospheric ethane and propane, Nature Communications, 11, 447, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14375-0, 2020. a

Brasseur, G. P., Kiehl, J. T., Müller, J.-F., Schneider, T., Granier, C., Tie, X. X., and Hauglustaine, D.: Past and future changes in global tropospheric ozone: Impact on radiative forcing, Geophysical Research Letters, 25, 3807–3810, https://doi.org/10.1029/1998gl900013, 1998. a

Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M., Crutzen, P., Boumard, F., Dauer, T., Dix, B., Ebinghaus, R., Filippi, D., Fischer, H., Franke, H., Frieβ, U., Heintzenberg, J., Helleis, F., Hermann, M., Kock, H. H., Koeppel, C., Lelieveld, J., Leuenberger, M., Martinsson, B. G., Miemczyk, S., Moret, H. P., Nguyen, H. N., Nyfeler, P., Oram, D., O'Sullivan, D., Penkett, S., Platt, U., Pupek, M., Ramonet, M., Randa, B., Reichelt, M., Rhee, T. S., Rohwer, J., Rosenfeld, K., Scharffe, D., Schlager, H., Schumann, U., Slemr, F., Sprung, D., Stock, P., Thaler, R., Valentino, F., van Velthoven, P., Waibel, A., Wandel, A., Waschitschek, K., Wiedensohler, A., Xueref-Remy, I., Zahn, A., Zech, U., and Ziereis, H.: Civil Aircraft for the regular investigation of the atmosphere based on an instrumented container: The new CARIBIC system, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 7, 4953–4976, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-4953-2007, 2007. a

Collins, W. J., Lamarque, J.-F., Schulz, M., Boucher, O., Eyring, V., Hegglin, M. I., Maycock, A., Myhre, G., Prather, M., Shindell, D., and Smith, S. J.: AerChemMIP: quantifying the effects of chemistry and aerosols in CMIP6, Geoscientific Model Development, 10, 585–607, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-10-585-2017, 2017. a

Derwent, R., Simmonds, P., O'Doherty, S., Manning, A., Collins, W., and Stevenson, D.: Global environmental impacts of the hydrogen economy, International Journal of Nuclear Hydrogen Production and Application, 1, 57–67, https://doi.org/10.1504/IJNHPA.2006.009869, 2006. a

Derwent, R. G., Stevenson, D. S., Utembe, S. R., Jenkin, M. E., Khan, A. H., and Shallcross, D. E.: Global modelling studies of hydrogen and its isotopomers using STOCHEM-CRI: Likely radiative forcing consequences of a future hydrogen economy, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 45, 9211–9221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.01.125, 2020. a

Ehhalt, D. H. and Rohrer, F.: The tropospheric cycle of H2: a critical review, Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology, 61B, 500–535, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0889.2009.00416.x, 2009. a, b, c, d

Ehhalt, D. H. and Rohrer, F.: The dependence of soil H2 uptake on temperature and moisture: a reanalysis of laboratory data, Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology, 63B, 1040–1051, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0889.2011.00581.x, 2011. a, b, c, d

Ehhalt, D. H. and Rohrer, F.: Deposition velocity of H2: a new algorithm for its dependence on soil moisture and temperature, Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology, 65, 19904, https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusb.v65i0.19904, 2013a. a, b, c

Ehhalt, D. H. and Rohrer, F.: Dry deposition of molecular hydrogen in the presence of H2 production, Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology, 65, 20620, https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusb.v65i0.20620, 2013b. a

Ellis, G. S. and Gelman, S. E.: Model predictions of global geologic hydrogen resources, Science Advances, 10, eado0955, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ado0955, 2024. a, b, c

Esquivel-Elizondo, S., Hormaza Mejia, A., Sun, T., Shrestha, E., Hamburg, S. P., and Ocko, I. B.: Wide range in estimates of hydrogen emissions from infrastructure, Frontiers in Energy Research, 11, 1207208, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2023.1207208, 2023. a

Fan, Z., Sheerazi, H., Bhardwaj, A., Corbeau, A.-S., Longobardi, K., Castañeda, A., Merz, A.-K., Woodall, C. M., Agrawal, M., Orozco-Sanchez, S., and Friedmann, J.: Hydrogen leakage: a potential risk for the hydrogen economy, The Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University, 33 pp., https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/file-uploads/HydrogenLeakageRegulations_CGEP_Commentary_063022.pdf (last access: 6 Septemer 2024), 2022. a

Galimova, T., Ram, M., and Breyer, C.: Mitigation of air pollution and corresponding impacts during a global energy transition towards 100 % renewable energy system by 2050, Energy Reports, 8, 14124–14143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.10.343, 2022. a

Ganzeveld, L., Bouwman, L., Stehfest, E., van Vuuren, D. P., Eickhout, B., and Lelieveld, J.: Impact of future land use and land cover changes on atmospheric chemistry-climate interactions, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 115, D23301, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010jd014041, 2010. a

Giglio, L., Randerson, J. T., and van der Werf, G. R.: Analysis of daily, monthly, and annual burned area using the fourth-generation global fire emissions database (GFED4), Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 118, 317–328, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrg.20042, 2013. a

GLDAS: GLDAS Soil Land Surface, https://ldas.gsfc.nasa.gov/gldas/soils (last access: 24 September 2024), 2024. a

Granier, C., Darras, S., Denier van der Gon, H., Doubalova, J., Elguindi, N., Galle, B., Gauss, M., Guevara, M., Jalkanen, J.-P., Kuenen, J., Liousse, C., Quack, B., Simpson, D., and Sindelarova, K.: The Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service global and regional emissions (April 2019 version), Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) report, 54 pp., https://doi.org/10.24380/d0bn-kx16, 2019. a

Guenther, A., Hewitt, C. N., Erickson, D., Fall, R., Geron, C., Graedel, T., Harley, P., Klinger, L., Lerdau, M., McKay, W. A., Pierce, T., Scholes, B., Steinbrecher, R., Tallamraju, R., Taylor, J., and Zimmerman, P.: A global model of natural volatile organic compound emissions, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 100, 8873–8892, https://doi.org/10.1029/94JD02950, 1995. a

Hand, E.: Hidden Hydrogen. Does Earth hold vast stores of a renewable carbon-free fuel?, Science, 379, 630–636, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh1460, 2023. a

Hauglustaine, D. A. and Ehhalt, D. H.: A three-dimensional model of molecular hydrogen in the troposphere, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 107, 4330, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD001156, 2002. a, b

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Hirahara, S., Horányi, A., Muñoz-Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Abdalla, S., Abellan, X., Balsamo, G., Bechtold, P., Biavati, G., Bidlot, J., Bonavita, M., De Chiara, G., Dahlgren, P., Dee, D., Diamantakis, M., Dragani, R., Flemming, J., Forbes, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A., Haimberger, L., Healy, S., Hogan, R. J., Hólm, E., Janisková, M., Keeley, S., Laloyaux, P., Lopez, P., Lupu, C., Radnoti, G., de Rosnay, P., Rozum, I., Vamborg, F., Villaume, S., and Thépaut, J.-N.: The ERA5 global reanalysis, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803, 2020. a

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Biavati, G., Horányi, A., Muñoz Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Rozum, I., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Dee, D., and Thépaut, J.-N.: ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present, Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) [data set], https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47, 2023. a, b

Houweling, S., Kaminski, T., Dentener, F., Lelieveld, J., and Heimann, M.: Inverse modeling of methane sources and sinks using the adjoint of a global transport model, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 104, 26137–26160, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JD900428, 1999. a

Hydrogen Council: Hydrogen for Net-Zero. A critical cost-competitive energy vector, 56 pp., https://hydrogencouncil.com/en/hydrogen-for-net-zero/ (last access: 6 September 2024), 2021. a, b, c, d

International Energy Agency: Energy Technology Perspectives 2020. Special Report on Carbon Capture Utilisation and Storage: CCUS in clean energy transitions, 174 pp., https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/energy/energy-technology-perspectives-2020-special-report-on-carbon-capture-utilisation-and-storage_208b66f4-en (last access: 6 September 2024), 2020. a

International Energy Agency: Global Hydrogen Review 2023, 176 pp., https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2023 (last access: 6 September 2024), 2023. a, b, c, d, e

Jöckel, P., Tost, H., Pozzer, A., Brühl, C., Buchholz, J., Ganzeveld, L., Hoor, P., Kerkweg, A., Lawrence, M. G., Sander, R., Steil, B., Stiller, G., Tanarhte, M., Taraborrelli, D., van Aardenne, J., and Lelieveld, J.: The atmospheric chemistry general circulation model ECHAM5/MESSy1: consistent simulation of ozone from the surface to the mesosphere, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 6, 5067–5104, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-6-5067-2006, 2006. a, b, c

Jöckel, P., Kerkweg, A., Pozzer, A., Sander, R., Tost, H., Riede, H., Baumgaertner, A., Gromov, S., and Kern, B.: Development cycle 2 of the Modular Earth Submodel System (MESSy2), Geoscientific Model Development, 3, 717–752, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-3-717-2010, 2010. a

Kaiser, J. W., Heil, A., Andreae, M. O., Benedetti, A., Chubarova, N., Jones, L., Morcrette, J.-J., Razinger, M., Schultz, M. G., Suttie, M., and van der Werf, G. R.: Biomass burning emissions estimated with a global fire assimilation system based on observed fire radiative power, Biogeosciences, 9, 527–554, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-527-2012, 2012. a

Kerkweg, A., Sander, R., Tost, H., and Jöckel, P.: Technical note: Implementation of prescribed (OFFLEM), calculated (ONLEM), and pseudo-emissions (TNUDGE) of chemical species in the Modular Earth Submodel System (MESSy), Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 6, 3603–3609, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-6-3603-2006, 2006. a, b

Klingmüller, K.: Hydrogen deposition velocity, Edmond [data set], https://doi.org/10.17617/3.PLYVTZ, 2025. a

Lamarque, J.-F., Bond, T. C., Eyring, V., Granier, C., Heil, A., Klimont, Z., Lee, D., Liousse, C., Mieville, A., Owen, B., Schultz, M. G., Shindell, D., Smith, S. J., Stehfest, E., Van Aardenne, J., Cooper, O. R., Kainuma, M., Mahowald, N., McConnell, J. R., Naik, V., Riahi, K., and van Vuuren, D. P.: Historical (1850–2000) gridded anthropogenic and biomass burning emissions of reactive gases and aerosols: methodology and application, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 7017–7039, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-7017-2010, 2010. a

Lan, X., Thoning, K. W., and Dlugokencky, E. J.: Trends in globally averaged CH4, N2O, and SF6 determined from NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory measurements, Version 2026-01, NOAA [data set], https://doi.org/10.15138/P8XG-AA10, 2026. a

Lelieveld, J., Berresheim, H., Borrmann, S., Crutzen, P. J., Dentener, F. J., Fischer, H., Feichter, J., Flatau, P. J., Heland, J., Holzinger, R., Korrmann, R., Lawrence, M. G., Levin, Z., Markowicz, K. M., Mihalopoulos, N., Minikin, A., Ramanathan, V., de Reus, M., Roelofs, G. J., Scheeren, H. A., Sciare, J., Schlager, H., Schultz, M., Siegmund, P., Steil, B., Stephanou, E. G., Stier, P., Traub, M., Warneke, C., Williams, J., and Ziereis, H.: Global Air Pollution Crossroads over the Mediterranean, Science, 298, 794–799, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1075457, 2002. a

Lelieveld, J., Gromov, S., Pozzer, A., and Taraborrelli, D.: Global tropospheric hydroxyl distribution, budget and reactivity, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 16, 12477–12493, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-12477-2016, 2016. a

Martin, A., Gayler, V., Steil, B., Klingmüller, K., Jöckel, P., Tost, H., Lelieveld, J., and Pozzer, A.: Evaluation of the coupling of EMACv2.55 to the land surface and vegetation model JSBACHv4, Geoscientific Model Development, 17, 5705–5732, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-5705-2024, 2024. a

Millington, R. J. and Quirk, J. P.: Permeability of Porous Media, Nature, 183, 387–388, https://doi.org/10.1038/183387a0, 1959. a

Nicely, J. M., Duncan, B. N., Hanisco, T. F., Wolfe, G. M., Salawitch, R. J., Deushi, M., Haslerud, A. S., Jöckel, P., Josse, B., Kinnison, D. E., Klekociuk, A., Manyin, M. E., Marécal, V., Morgenstern, O., Murray, L. T., Myhre, G., Oman, L. D., Pitari, G., Pozzer, A., Quaglia, I., Revell, L. E., Rozanov, E., Stenke, A., Stone, K., Strahan, S., Tilmes, S., Tost, H., Westervelt, D. M., and Zeng, G.: A machine learning examination of hydroxyl radical differences among model simulations for CCMI-1, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 20, 1341–1361, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-1341-2020, 2020. a

Novelli, P. C., Lang, P. M., Masarie, K. A., Hurst, D. F., Myers, R., and Elkins, J. W.: Molecular hydrogen in the troposphere: Global distribution and budget, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 104, 30427–30444, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JD900788, 1999. a

Ocko, I. B. and Hamburg, S. P.: Climate consequences of hydrogen emissions, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 22, 9349–9368, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-9349-2022, 2022. a

Paulot, F., Paynter, D., Naik, V., Malyshev, S., Menzel, R., and Horowitz, L. W.: Global modeling of hydrogen using GFDL-AM4.1: Sensitivity of soil removal and radiative forcing, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 46, 13446–13460, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.01.088, 2021. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p

Paulot, F., Pétron, G., Crotwell, A. M., and Bertagni, M. B.: Reanalysis of NOAA H2 observations: implications for the H2 budget, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 24, 4217–4229, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-4217-2024, 2024. a, b, c

Petron, G., Crotwell, A. M., Madronich, M., Moglia, E., Baugh, K. E., Kitzis, D., Mefford, T., DeVogel, S., Neff, D., Lan, X., Crotwell, M. J., Thoning, K., Wolter, S., and Mund, J. W.: Atmospheric Hydrogen Dry Air Mole Fractions from the NOAA GML Carbon Cycle Cooperative Global Air Sampling Network, 2009–2023, NOAA [data set], https://doi.org/10.15138/WP0W-EZ08, 2024. a, b

Pieterse, G., Krol, M. C., Batenburg, A. M., Steele, L. P., Krummel, P. B., Langenfelds, R. L., and Röckmann, T.: Global modelling of H2 mixing ratios and isotopic compositions with the TM5 model, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 11, 7001–7026, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-7001-2011, 2011. a

Plummer, D., Nagashima, T., Tilmes, S., Archibald, A., Chiodo, G., Fadnavis, S., Garny, H., Josse, B., Kim, J., Lamarque, J.-F., Morgenstern, O., Murray, L., Orbe, C., Tai, A., Chipperfield, M., Funke, B., Juckes, M., Kinnison, D., Kunze, M., Luo, B., Matthes, K., Newman, P. A., Pascoe, C., and Peter, T.: CCMI-2022: a new set of Chemistry–Climate Model Initiative (CCMI) community simulations to update the assessment of models and support upcoming ozone assessment activities, SPARC Newsletter, 22–30, https://www.aparc-climate.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/SPARCnewsletter_Jul2021_web.pdf (last access: 13 September 2025), 2021. a

Pöschl, U., von Kuhlmann, R., Poisson, N., and Crutzen, P. J.: Development and intercomparison of condensed isoprene oxidation mechanisms for global atmospheric modeling, Journal of Atmospheric Chemistry, 37, 29–52, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006391009798, 2000. a

Pozzer, A., Jöckel, P., and Van Aardenne, J.: The influence of the vertical distribution of emissions on tropospheric chemistry, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 9417–9432, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-9417-2009, 2009. a

Prather, M. J. and Zhu, L.: Resetting tropospheric OH and CH4 lifetime with ultraviolet H2O absorption, Science, 385, 201–204, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adn0415, 2024. a

Prather, M. J., Holmes, C. D., and Hsu, J.: Reactive greenhouse gas scenarios: Systematic exploration of uncertainties and the role of atmospheric chemistry, Geophysical Research Letters, 39, 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL051440, 2012. a, b, c

Price, H., Jaeglé, L., Rice, A., Quay, P., Novelli, P. C., and Gammon, R.: Global budget of molecular hydrogen and its deuterium content: Constraints from ground station, cruise, and aircraft observations, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 112, D22108, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD008152, 2007. a

Randerson, J. T., van der Werf, G. R., Giglio, L., Collatz, G. J., and Kasibhatla, P. S.: Global fire emissions database, version 4.1 (GFEDv4), ORNL DAAC [data set], https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1293, 2017. a, b

Reifenberg, S. F., Martin, A., Kohl, M., Bacer, S., Hamryszczak, Z., Tadic, I., Röder, L., Crowley, D. J., Fischer, H., Kaiser, K., Schneider, J., Dörich, R., Crowley, J. N., Tomsche, L., Marsing, A., Voigt, C., Zahn, A., Pöhlker, C., Holanda, B. A., Krüger, O., Pöschl, U., Pöhlker, M., Jöckel, P., Dorf, M., Schumann, U., Williams, J., Bohn, B., Curtius, J., Harder, H., Schlager, H., Lelieveld, J., and Pozzer, A.: Numerical simulation of the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on tropospheric composition and aerosol radiative forcing in Europe, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 22, 10901–10917, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-10901-2022, 2022. a

Rhee, T. S., Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M., Braß, M., and Brühl, C.: Isotopic composition of H2 from CH4 oxidation in the stratosphere and the troposphere, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 111, D23303, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JD006760, 2006. a, b

Righi, M., Hendricks, J., and Sausen, R.: The global impact of the transport sectors on atmospheric aerosol: simulations for year 2000 emissions, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 13, 9939–9970, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-9939-2013, 2013. a

Rodell, M., Houser, P. R., Jambor, U., Gottschalck, J., Mitchell, K., Meng, C.-J., Arsenault, K., Cosgrove, B., Radakovich, J., Bosilovich, M., Entin, J. K., Walker, J. P., Lohmann, D., and Toll, D.: The Global Land Data Assimilation System, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 85, 381–394, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-85-3-381, 2004. a

Roeckner, E., Bäuml, G., Bonaventura, L., Brokopf, R., Esch, M., Giorgetta, M., Hagemann, S., Kirchner, I., Kornblueh, L., Manzini, E., Rhodin, A., Schlese, U., Schulzweida, U., and Tompkins, A.: Report No 349: the atmospheric general circulation model ECHAM5, Part I, 133 pp., https://pure.mpg.de/pubman/faces/ViewItemOverviewPage.jsp?itemId=item_995269 (last access: 22 December 2024), 2003. a

Roeckner, E., Brokopf, R., Esch, M., Giorgetta, M., Hagemann, S., Kornblueh, L., Manzini, E., Schlese, U., and Schulzweida, U.: Report No. 354: the atmospheric general circulation model ECHAM5, Part II, 64 pp., https://pure.mpg.de/pubman/faces/ViewItemOverviewPage.jsp?itemId=item_995221 (last access: 22 December 2024), 2004. a

Roeckner, E., Brokopf, R., Esch, M., Giorgetta, M., Hagemann, S., Kornblueh, L., Manzini, E., Schlese, U., and Schulzweida, U.: Sensitivity of Simulated Climate to Horizontal and Vertical Resolution in the ECHAM5 Atmosphere Model, Journal of Climate, 19, 3771–3791, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI3824.1, 2006. a

Sand, M., Skeie, R. B., Sandstad, M., Krishnan, S., Myhre, G., Bryant, H., Derwent, R., Hauglustaine, D., Paulot, F., Prather, M., and Stevenson, D.: A multi-model assessment of the Global Warming Potential of hydrogen, Communications Earth & Environment, 4, 203, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00857-8, 2023. a, b

Sanderson, M. G., Collins, W. J., Derwent, R. G., and Johnson, C. E.: Simulation of Global Hydrogen Levels Using a Lagrangian Three-Dimensional Model, Journal of Atmospheric Chemistry, 46, 15–28, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024824223232, 2003. a

Saunois, M., Martinez, A., Poulter, B., Zhang, Z., Raymond, P. A., Regnier, P., Canadell, J. G., Jackson, R. B., Patra, P. K., Bousquet, P., Ciais, P., Dlugokencky, E. J., Lan, X., Allen, G. H., Bastviken, D., Beerling, D. J., Belikov, D. A., Blake, D. R., Castaldi, S., Crippa, M., Deemer, B. R., Dennison, F., Etiope, G., Gedney, N., Höglund-Isaksson, L., Holgerson, M. A., Hopcroft, P. O., Hugelius, G., Ito, A., Jain, A. K., Janardanan, R., Johnson, M. S., Kleinen, T., Krummel, P. B., Lauerwald, R., Li, T., Liu, X., McDonald, K. C., Melton, J. R., Mühle, J., Müller, J., Murguia-Flores, F., Niwa, Y., Noce, S., Pan, S., Parker, R. J., Peng, C., Ramonet, M., Riley, W. J., Rocher-Ros, G., Rosentreter, J. A., Sasakawa, M., Segers, A., Smith, S. J., Stanley, E. H., Thanwerdas, J., Tian, H., Tsuruta, A., Tubiello, F. N., Weber, T. S., van der Werf, G. R., Worthy, D. E. J., Xi, Y., Yoshida, Y., Zhang, W., Zheng, B., Zhu, Q., Zhu, Q., and Zhuang, Q.: Global Methane Budget 2000–2020, Earth System Science Data, 17, 1873–1958, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-17-1873-2025, 2025. a, b, c

Schultz, M. G., Diehl, T., Brasseur, G. P., and Zittel, W.: Air pollution and climate-forcing impacts of a global hydrogen economy, Science, 302, 624–627, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1089527, 2003. a

Seiler, W. and Conrad, R.: Contribution of tropical ecosystems to the global budgets of trace gases, especially CH4, H2, CO, and N2O, in: The Geophysiology of Amazonia: Vegetation and Climate Interactions, edited by: Dickinson, R. E., John Wiley, New York, 133–162 pp., ISBN 0471845116, 1987. a

Silver, B., Reddington, C. L., Chen, Y., and Arnold, S. R.: A decade of China’s air quality monitoring data suggests health impacts are no longer declining, Environment International, 197, 109318, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2025.109318, 2025. a

Smith-Downey, N. V., Randerson, J. T., and Eiler, J. M.: Temperature and moisture dependence of soil H2 uptake measured in the laboratory, Geophysical Research Letters, 33, L14813, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL026749, 2006. a

SPARC: SPARC Report on the Lifetimes of Stratospheric Ozone-Depleting Substances, Their Replacements, and Related Species, edited by: Ko, M., Newman, P., Reimann, S., and Strahan, S., 255 pp., https://www.aparc-climate.org/publications/sparc-reports/sparc-report-no-6/ (last access: 13 September 2025), 2013. a

The MESSy Consortium: The Modular Earth Submodel System Version 2.55.2_no-branch_b4754874_H2, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15211346, 2025. a

Tromp, T. K., Shia, R.-L., Allen, M., Eiler, J. M., and Yung, Y. L.: Potential environmental impact of a hydrogen economy on the stratosphere, Science, 300, 1740–1742, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1085169, 2003. a

Truche, L., Donzé, F.-V., Goskolli, E., Muceku, B., Loisy, C., Monnin, C., Dutoit, H., and Cerepi, A.: A deep reservoir for hydrogen drives intense degassing in the Bulqizë ophiolite, Science, 383, 618–621, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adk9099, 2024. a

Warneck, P.: Chemistry of the Natural Atmosphere, International Geophysics Series, Vol. 41, Academic Press, San Diego, 757 pp., ISBN 9780080954684, 1988. a

Warwick, N., Griffiths, P., Keeble, J., Archibald, A., Pyle, J., and Shine, K.: Atmospheric implications of increased Hydrogen use, University of Cambridge and University of Reading, 75 pp., https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/624eca7fe90e0729f4400b99/atmospheric-implications-of-increased-hydrogen-use.pdf (last access: 22 December 2024), 2022. a

Warwick, N. J., Bekki, S., Nisbet, E. G., and Pyle, J. A.: Impact of a hydrogen economy on the stratosphere and troposphere studied in a 2-D model, Geophysical Research Letters, 31, L05107, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL019224, 2004. a

Warwick, N. J., Archibald, A. T., Griffiths, P. T., Keeble, J., O'Connor, F. M., Pyle, J. A., and Shine, K. P.: Atmospheric composition and climate impacts of a future hydrogen economy, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 23, 13451–13467, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-13451-2023, 2023. a, b

Xiao, X., Prinn, R. G., Simmonds, P. G., Steele, L. P., Novelli, P. C., Huang, J., Langenfelds, R. L., O'Doherty, S., Krummel, P. B., Fraser, P. J., Porter, L. W., Weiss, R. F., Salameh, P., and Wang, R. H. J.: Optimal estimation of the soil uptake rate of molecular hydrogen from the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment and other measurements, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 112, D07303, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD007241, 2007. a, b

Yang, L. H., Jacob, D. J., Lin, H., Dang, R., Bates, K. H., East, J. D., Travis, K. R., Pendergrass, D. C., and Murray, L. T.: Assessment of Hydrogen's Climate Impact Is Affected by Model OH Biases, Geophysical Research Letters, 52, e2024GL112445, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL112445, 2025. a

Yashiro, H., Sudo, K., Yonemura, S., and Takigawa, M.: The impact of soil uptake on the global distribution of molecular hydrogen: chemical transport model simulation, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 11, 6701–6719, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-6701-2011, 2011. a, b, c

Yokelson, R. J., Saharjo, B. H., Stockwell, C. E., Putra, E. I., Jayarathne, T., Akbar, A., Albar, I., Blake, D. R., Graham, L. L. B., Kurniawan, A., Meinardi, S., Ningrum, D., Nurhayati, A. D., Saad, A., Sakuntaladewi, N., Setianto, E., Simpson, I. J., Stone, E. A., Sutikno, S., Thomas, A., Ryan, K. C., and Cochrane, M. A.: Tropical peat fire emissions: 2019 field measurements in Sumatra and Borneo and synthesis with previous studies, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 22, 10173–10194, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-10173-2022, 2022. a

Yonemura, S., Yokozawa, M., Kawashima, S., and Tsuruta, H.: Model analysis of the influence of gas diffusivity in soil on CO and H2 uptake, Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology, 52B, 919–933, https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusb.v52i3.17075, 2000. a, b

Zimmermann, P. H., Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M., Pozzer, A., Jöckel, P., Winterstein, F., Zahn, A., Houweling, S., and Lelieveld, J.: Model simulations of atmospheric methane (1997–2016) and their evaluation using NOAA and AGAGE surface and IAGOS-CARIBIC aircraft observations, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 20, 5787–5809, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-5787-2020, 2020. a, b, c, d, e, f

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Materials and methods

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusions

- Appendix A: List of observational stations

- Appendix B: Additional results

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Materials and methods

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusions

- Appendix A: List of observational stations

- Appendix B: Additional results

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement